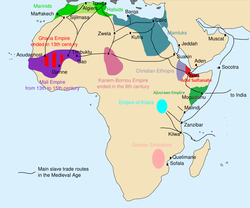

There were many kingdoms and empires in all regions of the continent of Africa throughout history. A kingdom is a state with a king or queen as its head.[1] An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant centre and subordinate peripheries".[2]

In Africa states emerged in a process covering many generations and centuries. Most states were created through conquest or the borrowing and assimilation of ideas and institutions, while some developed through internal, largely isolated development.[3] Economic development "gave rise to a perceived need for centralized institutions and 'territorial' leadership that transcended older bonds of kinship and community". The politicoreligious struggle between the people and the king sometimes saw the people victorious and the establishment of sacred kings with little political power (termed "adverse sacralisation"), contrasted with divine kings equated to gods.[4] Kings and queens used both "instrumental power", the employment of direct influence to achieve a desired outcome, and "creative power", the use of ritual and mythology.[a][6]: 21–23

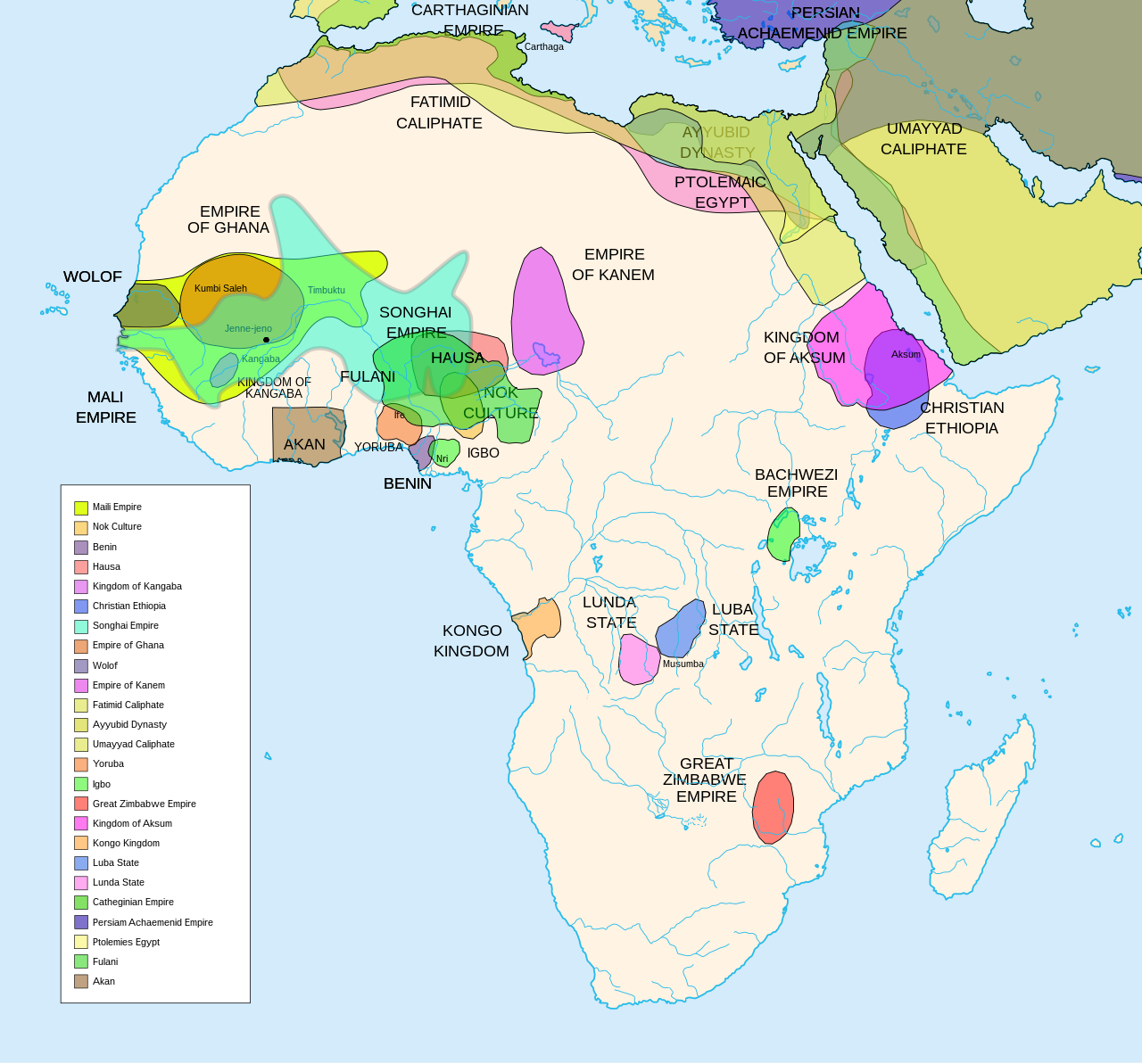

Despite this, popular understanding often claims that the continent lacked large states or meaningful complex political organisation. Whether rooted in ignorance, Eurocentrism, or racism, famous historians such as Hugh Trevor-Roper have argued that African history is not characterised by state formation or hierarchical structures. In fact, the nature of political organisation varied greatly across the continent, from the expansive West Sudanic empires, to the sacral Congolese empires akin to confederations or commonwealths, and the immensely hierarchical kingdoms of the Great Lakes.[7]

The vast majority of states included in this list existed prior to the Scramble for Africa (c. 1880–1914) when, driven by the Second Industrial Revolution, European powers rapidly invaded, conquered, and colonised Africa. While most states were conquered and dissolved, some kings and elites negotiated the terms of colonial rule,[6]: 15 and traditional power structures were incorporated into the colonial regimes as a form of indirect rule.[8]

In the mid-late 20th century decolonisation saw Africans inherit the former colonies,[9] and many traditional kingdoms still exist today as non–sovereign monarchies. The roles, powers, and influence of traditional monarchs throughout Africa varies greatly depending on the state. In some states, such as Angola, the local monarch may play an integral role in the local governing council of a region.[10] On the flipside their powers may be curtailed, as happened in 2022 with Wadai in Chad,[11] or their positions abolished, as happened in Tanzania in 1962,[12] and in 1966 in Uganda with Buganda, which was later restored in 1993.[13] In this list they are labelled (NSM).

There are only three current sovereign monarchies in Africa;[14] two of which (Lesotho and Morocco) are constitutional monarchies where the rulers are bound by laws and customs in the exercise of their powers, while one (Eswatini) is an absolute monarchy where the monarch rules without bounds.[15]: 15 Sovereign monarchies are labelled (SM).

There have been a number of autocratic presidents in Africa who have been characterised as "disguised monarchs" due to the absence of term limits,[16] as well as those who have invoked hereditary succession in order to preserve their regimes,[17] such as the Bongos of Gabon,[18] Gnassingbés of Togo,[19] or Aptidon and Guelleh of Djibouti,[20] attracting the terms monarchical republic and presidential monarchism.[18][16] These haven't been included.

Criteria for inclusion

Only polities that were once independent and described as kingdoms or empires by reliable sources are included. The intercontinental Islamic empires that covered parts of North and Northeast Africa are not included, and should be discussed as part of the Muslim world, however the residual fragments that had their capital on the continent of Africa are.

Oral traditions rarely incorporate chronological devices,[21]: 29 and dates in this list are often estimates based on lists of rulers.[22] Dates have [one date for loss of independence] / [one date for loss of nominal rule]. Additional information such as notable articles may accompany entries.

Comparison between kingdoms

Historian Jan Vansina (1962) discusses the classification of Sub–Saharan African Kingdoms, mostly of Central, South and East Africa, with some additional data on West African (Sahelian) Kingdoms distinguishing five types, by decreasing centralization of power:[23]

- Despotic Kingdoms: Kingdoms where the king controlled the internal and external affairs directly and personally appointed overseers. The king kept a monopoly on the use of force. Examples include Rwanda, Nkore/Ankole, and Kongo of the 16th century.

- Regal Kingdoms: Kingdoms where the king controlled the external affairs directly, and the internal affairs via a system of overseers where most local chiefs kept their positions but not their autonomy after conquest. The king and most of his administration belonged to the same religion, group and/or family.

- Incorporative Kingdoms: Kingdoms where the king only controlled the external affairs and the nucleus with no permanent administrative links between him and the chiefs of the provinces. The local chiefs of the provinces were left largely undisturbed after conquest. Examples are the Bamileke, Luba and the Lozi.

- Aristocratic Kingdoms: The only link between central authority and the provinces was payment of tribute which symbolised subordination. These kingdoms were kept together by the superior military strength of the nucleus. This type is rather common in Africa, examples include Kongo of the 17th century, Kazembe, Kuba, the Ha, and Chagga states of the 18th century.

- Federations: Kingdoms where the external affairs were regulated by a council of elders headed by the king, who is simply primus inter pares, such as in the Ashanti Union. (Confederations are not included; see "List of confederations")

North Africa

A non-exhaustive list of kingdoms and empires in North Africa that we have record of:

4th millennium BCE – 6th century CE

- Protodynastic period in Egypt: (preceded by various cultures in which it is unclear if the institution of kingship existed) (preceded by nomes and nomarchs)

- Lower Egypt Kingdom (3500–3100 BCE)

- Upper Egypt Kingdom (3400–3150 BCE)

- Early Dynastic Egypt[24] (3150–2686 BCE)

- Old Kingdom of Egypt[25] (2686–2181 BCE)

Old and Middle Kingdoms of Ancient Egypt - Kingdom of Kerma (2500–1500 BCE)

- First Intermediate Period in Egypt: (2181–2055 BCE)

- Middle Kingdom of Egypt[26] (2055–1650 BCE)

- Second Intermediate Period in Egypt (1700–1550 BCE)

- 14th dynasty at Xois (1700–1650 BCE)

- 15th dynasty and the Hyksos (1650–1550 BCE)

- Abydos dynasty (1640–1620 BCE)

- 16th dynasty (1650–1580 BCE)

- 17th dynasty (1571–1540 BCE)

- New Kingdom of Egypt (1550–1077 BCE)

- Third Intermediate Period in Egypt: (1077–664 BCE)

- 21st dynasty (1077–943 BCE)

- 22nd dynasty (943–716 BCE)

- 23rd dynasty (837–728 BCE)

- 24th dynasty (732–720 BCE)

- Kingdom of Kush (1070 BCE – 350 CE) and the 25th dynasty of Egypt/Kushite Empire (754–656 BCE)

- Ancient Carthage (814–146 BCE)

- Late Dynastic Egypt (664–525 BCE, 404–343 BCE)

- Battiadae Kingdom (631–440 BCE) (List of kings of Cyrene)

- Garamantes Kingdom (pre 5th century BCE – 7th century CE)

- Kingdom of Blemmyes (600 BCE – 3rd century CE)

- Ptolemaic Kingdom (305–30 BCE)

- Kingdom of Numidia (202–46 BCE) (preceded by Massylii Confederation)

- Kingdom of Mauretania (202 BCE – 25 BCE/44 CE)

- Kingdom of Nobatia (350–650 CE) (absorbed into Makuria)

- Kingdom of Ouarsenis (430–735 CE) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Kingdom of the Vandals and Alans (435–534 CE)

- Kingdom of the Moors and Romans (477–599 CE)

- Kingdom of the Aurès (484–703 CE) (Kahina) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Kingdom of Makuria (5th century–1518 CE) (Dongola as an interchangeable name prior to 1365? "[27]" and Qalidurut, in which there are contrasting titles for the same king) (its rump state after the 1365 civil war is often conflated as Dotawo and it is unknown whether the other polity in the civil war continued to hold Dongola prior to Funj conquest)

- Kingdom of Hodna[28]: 508 (5th century–7th century CE) (Hodna) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Kingdom of Capsus (5th century–6th/7th century CE) (Gafsa) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Ucutumani Kingdom (?–?) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Nemencha Kingdom (5th century–7th century CE) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Lagautan/Tripolis/Cabaon Kingdom (5th century–7th century CE) (Cabaon) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Kingdom of the Dorsale[29] (510–7th century CE) (Romano-Berber kingdoms)

- Kingdom of Altava (578–708 CE) (Kusaila of Awraba) (Roman–Berber kingdoms)

- Principality of Tingitana[28]: 508 (6th century–7th century CE) (Mauretania Tingitana)

- Kingdom of Alodia/Alwa (6th century–1504 CE)

7th century – 12th century CE

- Dar Sila 'Wandering Sultanate'[30] (619–? CE)

- Emirate of Nekor (710–1019 CE)

- Barghawata/Tamasna Kingdom[31] (744–1058 CE) (Salih ibn Tarif)

- al–Rahman's Ifriqiya (745–755 CE)

- Ifranid Emirate of Tlemcen (757–790 CE) (Algeria)

Almoravid Empire - Emirate of Sijilmassa (759–976 CE)

- Rustamid Imamate of Tahert (767–909 CE) (Algeria) (Tahert)

- Idrisid dynasty (789–974 CE) (Morocco)

- Imamate of Nafusa (8th century–911 CE)

- Aghlabid dynasty (800–909 CE) (Tunisia)

- Sulaymanid dynasty (814–922 CE) (Algeria)

- Tulunid dynasty (868–905 CE) (Egypt)

- Fatimid Caliphate (910–1171 CE) (born from Danhāǧa Confederation)

- Banu Khattab dynasty (918–1172/1177 CE) (Zawila) (Libya)

- Ikhshidid dynasty (935–969 CE) (Egypt) (Abu al–Misk Kafur)

- Banu Kanz dynasty (948–1365 CE) (Egypt/Sudan)

- Maghrawa dynasty (988–1069 CE) (Morocco)

- Banu Khazrun dynasty (1001–1146 CE) (Libya)

- M'zab (1012–16th century/1882 CE)

- Hammadid dynasty (1014–1152 CE) (Algeria) (born from Danhāǧa Confederation)

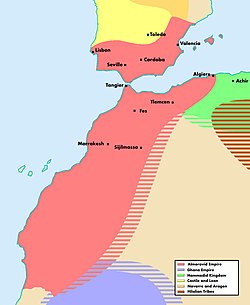

- Almoravid dynasty (1040–1147 CE) (Morocco and Western Sahara) (born from Aznag Confederation)

- Zirid dynasty (1048–1148 CE) (Algeria) (born from Danhāǧa Confederation)

- Khurasanid dynasty (1059–1128 CE, 1148–1158 CE) (Tunisia)

- Banu Ghaniya dynasty[32] (1180–1212 CE) (Tunisia)

- Almohad dynasty (1121–1269 CE) (Morocco) (born from Masmuda Confederation) (Tinmel)

- Ayyubid dynasty (1171–1254 CE) (Egypt)

Fatimid Caliphate - Guanches Guanartematos: (pre–15th century CE) (Gran Canaria)

- Daju kingdom (12th century–15th century CE) preceded by Tora (overthrown by Tunjur)

13th century – 18th century CE

- Emirate of Banu Talis (1228–1551 CE)

- Hafsid dynasty (1229–1574 CE) (Tunisia) (born from Masmuda Confederation)

- Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen (1235–1556 CE) (Algeria) (born from Zenata Confederation)

- Marinid dynasty (1248–1465 CE) (Morocco) (born from Zenata Confederation)

- Mamluk Sultanate (1250–1517 CE)

- Bahri dynasty (1250–1382 CE)

- Burji dynasty (1382–1517 CE)

- Banu Makki dynasty (1282–1394 CE) (Tunisia)

- Hafsid Emirate of Béjaïa/Bougie (1285–1510 CE)

- Kingdom of al–Abwab (13th century–15th/16th century CE)

- Hafsid Emirate of Qusantina/Constantine[33] (CE 13th/14th century–1528) (Constantine)

- Banu Thabit dynasty (1324–1401 CE) (Libya)

- Zab Emirate (mid 14th century–1402 CE)

- Sultanate of Tuggurt (1414–1854/1871 CE) (vassal of Algiers (CE 1552–1812/1827)) (List of rulers of Tuggurt)

- Wattasid dynasty (1470–1554 CE) (Morocco) (born from Zenata Confederation)

- Tunjur kingdom (15th century–mid 17th century CE) (overthrown by Darfur)

- Abdallabi Kingdom (15th century–1504/1821 CE)

Senussi Order including sphere of influence circa 1880 - Kingdom of Fazughli (1500–1685 CE)

- Sultanate of Sennar/Funj (1504–1821 CE)

- Saadi Principality of Sus and Tagmadert (1509–1554 CE) (Sous) (at times ruled separately from Saadi Sultanate)

- Kingdom of Beni Abbas (1510–1872 CE)

- Kingdom of Kuku (1515–1638 CE)

- Regency of Algiers (1516/1659–1830 CE) (Odjak of Algiers Revolution)

- Fezzan Sultanate (1556–1804/1912 CE)

- Saadi dynasty (1554–1659 CE) (Morocco)

- Regency of Tunis (1574/1591/1613–1705 CE) (Muradid dynasty) succeeded by Beylik of Tunis (1705–1881 CE) (Husainid dynasty)

- Naqsid Principality of Tetouan (1597–1673 CE)

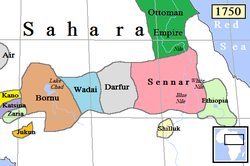

- Sultanate of Darfur (1603–1874 CE, 1898–1916 CE) (Keira dynasty)

- Republic of Bou Regreg (1627–1668 CE) (Elective monarchy?)

- Dila'iya Sultanate (1637–1668 CE)

- Alaouite dynasty (1666 CE–current) (SM of Morocco) (Makhzen)

- Dar Tama Sultanate[34][30]: 450 (17th century CE–?) (Tama people)

- Tazerwalt (17th century CE)

- Regency of Tripoli (1551/1711–1835/1912 CE) (Karamanli dynasty)

- Taqali Kingdom (1750–1884 CE, 1889–1969 CE) (Tagale people)

19th century CE – present

- Emirate of Abdelkader/Mascara (1832–1847 CE)

- Dar Qimr Sultanate[34][30]: 450 (1850–?/1945 CE) (mentioned in Sultan#West Asia and North Africa)

- Mahdist State (1885–1889 CE)

- Dar Masalit Sultanate[34] (19th century–early 20th century CE)

- Muhammad Ali dynasty (1914–1951 CE) (Egypt)

- Emirate of Cyrenaica (1949–1951 CE)

- Senussi dynasty (1951–1969 CE) (Libya) preceded by Senusiyya (1837 CE–present)

- Kingdom of Tunisia (1956–1957 CE)

East Africa

A non-exhaustive list of kingdoms and empires in East Africa that we have record of:

4th millennium BCE – 6th century CE

- Kingdom of Punt (2500–980 BCE)

- Ancient Somali city–states (1000 BCE – various CE)

- Macrobian Kingdom (1000–500 BCE)

- Kingdom of Dʿmt (980–650 BCE)

- Azania (?–1st century CE) (Rhapta) (Southern Cushitic people and the Bantu expansion)

- Aksumite/Axumite Empire[35] (50–960 CE) (List of kings of Axum) (preceded by various city-states)

- Harla Kingdom (501–1500 CE)

7th century – 12th century CE

- Sultanate of Dahlak (7th century–16th century CE)

- Swahili city states (8th century–various CE) (Bantu expansion and Zanj) (List of historic Swahili coast settlements)

- Sultanate of Shewa/Shoa (896–1286 CE) (List of rulers of Shewa)

- Hubat (9th century–14th century CE)

- Gidaya (9th century–14th century CE)

- Hargaya (9th century–14th century CE)

- Mora (9th century–14th century CE)

- Giddim[37] (?–17th century CE)

- Beja Kingdoms:

- Tunni Sultanate (9th century – 13th century CE)

- Malindi Kingdom (9th century–15th century CE)

Sultanate of Kilwa 1310 CE - Kilwa Sultanate (957–1513 CE)

- Shirazi dynasty (957–1277 CE)

- Mahdali dynasty (1277–1495 CE) succeeded by 3 Portuguese coups until 1513 CE

- Kingdom of Semien/Falasha (960–1137 CE) (Beta Israel) (only according to legend)

- Kingdom of Damot (10th/13th century–1317 CE) (possibly same as Wolaita)[39]: 59 neighbouring Bizamo[40]

- Empire of Kitara[41] (10th century–15th century CE) preceded by Bugangaizi[42] (Tembuzi dynasty/Batembuzi followed by Chwezi dynasty/Bachwezi)

- Fatagar Sultanate (11th century–14th century CE)

- Wäj[37] (?–? CE)

- Ganz[43] (?–? CE)

- Kingdom of Gisaka (11th century–1854 CE) (Gesera clan), splintered into Busozo and Bushiru[44]: 517

- Zagwe dynasty (1137–1270 CE)

- Sultanate of Arababni (12th century–16th century CE)

- Wanga Kingdom (12th century–1895/present CE) (NSM of Kenya) (List of rulers of Wanga)

13th century – 18th century CE

- Pate Sultanate (1203–1895 CE) (List of rulers of Pate) subordinate sultanates?:

- Kingdom of Wolaita/Welayta (1251–1896 CE) (possibly same as Damot)[39]: 59

- Ethiopian Empire (1270–1974 CE)

- Sultanate of Ifat (1285–1415 CE) (Walashma dynasty)

- Dawaro Emirate (pre–13th century/18th century CE)

- Dankali Sultanate (13th century–18th century CE)

- Ugweno/Upare Kingdom[45]: 414 (13th century–15th century/1881/1962 CE) (Shana dynasty followed by Suya dynasty) (Pare people)

- Hadiya Sultanate (13th century–15th century CE, 17th century–19th century CE)

- Sultanate of Dara[43][46]: 349 (?–? CE)

- Sultanate of Sara/Sarha[46]: 349 (?–? CE)

- Sultanate of Mogadishu (13th century–16th century CE)

- Sultanate of Bale/Bali[47]: 86 (13th century–16th century CE)

- Dobe'a[48] (?–? CE)

- Kingdom of Rwanda[23]: 332–333 (1350–1897/1962 CE) (NSM in Rwanda) (Gihanga) (Nyiginya) (preceded by Singa, Zigaba and Gesera as the oldest, Banda, Cyaba, Ongera and Enengwe)[44]: 516

- Ajuran Sultanate (14th century–17th century CE) preceded by the Garen Kingdom [citation needed]

- Sharkha Sultanate[43][47]: 86 (pre–14th century CE)

- Gonga kingdoms: (Gonga languages)

- Kingdom of Kaffa (1390–1897 CE)

- Ennarea/Inariya Kingdom (14th century–1710 CE) succeeded by Kingdom of Limmu–Ennarea (1801–1891 CE) (List of rulers of Ennarea)

- Kingdom of Garo/Bosha (1567–1883 CE) (List of rulers of Garo)

- Bizamo[49][50] (?–? CE)

- Konch kingdom[49][50] (?–? CE)

- Boro kingdom[49][50] (?–? CE) (Boro language)

- Kingdom of Anfillo[50] (late 16th century-late 19th century) (Anfillo language)

- Kitagwenda Kingdom (1390–1901 CE) (incorporated into Tooro)

- Early Luo Kingdoms:[51] (9 states by 1750 CE)

- Tekedi Kingdom[44]: 507 (early 15th century–mid 16th century CE)

- Palwo/Paluo/Biito/Babito kingdoms (subset of Luo)[52]

- Pawir Kingdom[51]: 381–393 [44]: 508–512 (pre 15th century CE–?) (later a province of Bunyoro)

- (Lira Paluo, Paimol; not primarily Palwo/Paluo states: Padibe, Patongo, Alur/Alero and Koc)[51]: 381–393

- Wipac Kingdom[51]: 392–393 (pre 15th century CE–?)

- Kingdom of Bunyoro[23] (14th century–1899/present CE) (NSM in Uganda) (Omukama of Bunyoro) (not to be confused with Empire of Kitara, its predecessor)

- Busongora Kingdom[53] (14th century/1725–1906/present CE) (NSM in Uganda) (Songora people) (incorporated into Ankole)

- Adal Sultanate (1415–1555 CE)

- Kingdom of Karagwe[54] (1450–1890s/1963 CE)

- Shilluk Kingdom[23]: 332–333 (1490–1861/present CE) (NSM in South Sudan)

- Nkore/Ankole Kingdom[23]: 332–333 (1430–1901/1967CE) (NSM in Uganda) (called Nkore before 1914 when, under British administration, it was combined with several states to form Ankole)

- Angoche Sultanate (1485/1513–1910 CE)

- Alur Kingdom[23]: 332–333 (1490/1630–?/present CE) (NSM in Uganda) (Alur people#Alur Kingdom)

African Great Lakes Kingdoms, c.1880 - Yamma/Janjero Kingdom (15th century–1894 CE)

- Sultanate of Tadjourah (15th century–1884 CE)

- Mubari Kingdom (15th century–16th century/18th century CE) (Zigaba clan)

- Busigi Kingdom[44]: 517 (15th century–?/early 20th century CE)

- Kingdom of Buzinza[55] (15th century–? CE)

- Kingdom of Buganda[51]: 393–395 (13th/14th century–1884/present CE) (NSM in Uganda) (Kabaka of Buganda) (Lukiiko)

- Maore Sultanate[56]: 436–438 (1500–1832/1835 CE) (List of sultans of Maore)

- Ndzuwani Sultanate[56]: 436–438 (1500–1866/1886/1912 CE) (Anjouan) (List of sultans of Ndzuwani)

- Agĩkũyũ (1512–1888/1895 CE) (Kikuyu people)

- Vazimba Kingdoms (pre–1547 CE) (uncertain regarding total) (Andriandravindravina) (Twelve sacred hills of Imerina):

- Menabe Kingdom (1540–1834 CE)

- Kingdom of Imerina/Madagascar (1540–1897 CE) (NSM in Madagascar) (List of Imerina monarchs) (4 states emerged in the civil war, to later be reunited): (1710–1787 CE)

- Mombasa Sultanate (1547–1826 CE) (List of rulers of Mombasa)

- Gadabuursi Ughazate (1575/1607–1884)

- Imamate of Aussa (1577–1734 CE) succeeded by Sultanate of Aussa (1734–1865/1975 CE, 1991 CE–present) (NSM in Ethiopia)

- Mäzäga/Säläwa[57] (pre-16th century CE) (Ga'ewa) (conquered by Ethiopia)

- Busoga kingdoms[23]: 332–333 (CE 16th century–late 19th century/present) (NSM in Uganda) (only formed a federation in 1906 under British administration, some of its federates (32) are also NSMs in Uganda) (Kyabazinga of Busoga) (Lukiiko):

- Group of 6 kingdoms:

- Group of 5 principalities:

- Bulamogi (1550 CE–?/present)

- Bukono (pre 1656–1896/present CE)

- Luuka/Luzinga (pre 1737 CE–?/present)

- Kigulu (1737–1896 CE)

- Kigulu–Buzimba (1806–1899 CE) (split from Kigulu, later reunited under British administration)

- Bugabula

- Kingdom of Bugesera (16th century–1799 CE) (partitioned between Rwanda and Burundi)

- Teso Kingdom[58] (16th century CE–?) (Teso people)

- Kayonza Kingdom[59] (16th century CE–?)

- Kingizi Kingdom[59] (16th century CE–?)

- Grande Comore Sultanates[56]: 436–438 (16th century–19th century CE): (united into Ndzuwani /Anjouan in 1886)

- Bambao, Itsandra, Mitsamihuli, Washili, Badgini/Bajini, Hambuu, Hamahame, Mbwankuu, Mbude and Domba

- Antemoro Kingdom[56] (16th century–late 19th century CE) (Antemoro people)

- Sultanate of Rehayto (1600–1891/1902 CE) (Rahayta)

- Antankarana Kingdom[60][61] (1614–1835/present CE) {Antankarana)

- Bara/Zafamanely Kingdom[62] (1640–1800 CE) (Bara people) (fractured into 3 major kingdoms and 24 minor kingdoms)

- Emirate of Harar (1526/1647–1875/1884 CE)

- Majeerteen Sultanate (1648–1889/1927 CE) (NSM in Somalia)

- Mahafaly Kingdoms[56] (pre 1650 CE–?) (Mahafaly) (previously united?)[56]: 426

- Sakatovo (1650 CE–?)

- Menarandra (1650 CE–?)

- Linta (1670 CE–?) (split from Menarandra)

- Onilahy (1750 CE–?) (split from Menarandra)

- Kingdom of Mpororo/Ndorwa[59]: 17 (1650–1753 CE) (Hororo people) (Muhumusa) (created as buffer state between Rwanda and Busongora) succeeded by: (all were incorporated into Nkore/Ankole)

- Gojjam (1620–1855 CE)

- Kingdom of Burundi/Urundi[23]: 332–333 (1675–1890/1966 CE) (List of kings of Burundi)

- Boina/Iboina Kingdom (1690–1820/1840 CE)

- Guingemaro (pre-17th century CE)

- Bukunzi Kingdom (pre 17th century CE–?)

- Kinkoko/Cyinkoko Kingdom[51]: 398 (pre 17th century CE–?)

- Buhoma Kingdom[51]: 398 (pre 17th century CE–?)

- Bahavu Kingdom[51]: 398 [63] (pre 17th century CE–?) (NSM in Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Rusubi/Ussuwi Kingdom[51]: 398 [64] (pre 17th century CE–?, ?–early 19th century CE) (seceded from Buzinza)[51]: 402 (appears to have split in two?)

- Kimwani Kingdom[65] (pre 17th century CE–?) (seceded from Buzinza) (near Biharamulo, so not the Mwani people?)[54]: 7

- Bukerebe/Ukerebe[51]: 398–402 [66] (pre 17th century CE–?)

- Betsileo Kingdoms:[67] (Betsileo people)

- Lalangina

- Isandra

- Fandriana

- Fisakana

- Manandriana (1750–1800 CE)

- Antaisaka/Tesaka Kingdom[56]: 849 (17th century–1853 CE) (Antaisaka people)

- Anosy/Zafimanara Kingdom[56]: 849 (17th century–19th century CE) (Antanosy people) (Zafiraminia)

- Sakalava Empire[68] (17th century–1896/present CE) (Sakalava people) (fractured into NSMs in Madagascar)

- Sultanate of the Geledi (late 17th century–1902/1908 CE)

- Milansi[69][70] (17th century–1700) succeeded by Nkansi and Lyangalile[70] (Fipa people and Twa)

- Haya Kingdoms:[71][23]: 332–333 (17th century–late 19th century CE) (Haya people) (Kagera Region)

- Kyamtwara (pre–late 18th century CE) succeeded by Maruku, Bugabo and Lesser Kyamtwara (late 18th century–1890/1961 CE)

- Kiziba (pre–1890/1961 CE)

- Ihangiro (pre–1890/1961 CE)

- Kianja/Kiyanja/Kyanja/Kihanja (pre–1890/1961 CE)

- Chagga states:[23]: 332–333 (CE 17th century–1886/1961) (37 in total):

- Betsimisaraka Kingdom[56]: 433–434 (1710–1817 CE) (Betsimisaraka people) (preceded by Antavaratra and Antatsimo/Betanimena)

Horn Of Africa 1915 - Kingdom of Kooki (1720–1896/2004/present CE) (NSM in Uganda)

- Isaaq Sultanate (1749–1884/present CE) (NSM in Somaliland)

- Habr Yunis Sultanate (1769–1907/1917/present CE) (NSM in Somaliland)

- Shambaa/Shambala Kingdom[45]: 414 (1730s–1885 CE) (NSM in Tanzania) (Shambaa people) (Kilindi dynasty)

- Kingdom of Gumma (1770–1885/1902 CE) (List of rulers of Gumma)

- Kingdom of Jimma (1790–1884/1889/1932 CE) (List of rulers of Jimma)

- Buha Kingdoms[73] (18th century–late 19th century CE): (Ha people)

- Heru (called Oha initially by outside traders)

- Nkalinzi/Manyovu

- Bushingo/Ushingo

- Muhambwe

- Buyungu

- Luguru/Ruguru

- Bujiji/Ujiji (Jiji people)

- Bushubi[74][51]: 381–393

- Buzimba Kingdom (pre 18th century–1870/1901 CE) (incorporated into Ankole)

- Buhweju Kingdom (pre 18th century–1901 CE) (incorporated into Ankole)

- Bunyaruguru Kingdom (pre 18th century–1901 CE) (incorporated into Ankole)

- Tandroy/Zafimaniry Kingdom[75][76] (early 18th century–1790/? CE) (Antandroy) (same as/separate from the Anosy Kingdom?)

- Habr Awal Sultanate (18th century–1884/present CE) (NSM in Somaliland)

- Antaifasy Kingdom[56]: 849 (18th century–1827/1896 CE) (Antaifasy)

- Sultanate of Goba'ad (18th century–1885/? CE)

- Zafirambo/Tanala Kingdom[77][78] (18th century CE) (Tanala) (split into Manambondro and Sandrananta)

- Kingdom of Isandra (18th century–? CE)

- Benzanozano Kingdom[56]: 879 (late 18th century CE) (Bezanozano) (only had one king)

19th century CE – present

- Bassar Kingdom[79] (1800 CE–?/present)

- Tumbuka Kingdom (1805–1891/present CE) (NSM of Malawi) (Tumbuka people)

- Wituland (1810–1885/1923 CE) (List of rulers of Witu)

- Ibanda Kingdom (1814–1902 CE) (incorporated into Ankole)

- Kingdom of Gomma (early 19th century–1886 CE) (List of rulers of Gomma)

- Tooro Kingdom[80] (1830–1876/present CE) (NSM in Uganda)

- Mwali Sultanate[56]: 436–438 (1830–1886/1909 CE) (Mohéli) (List of sultans of Mwali)

- Kingdom of Gera (1835–1887 CE) (List of rulers of Gera)

- Nkhotakota Sultanate (1840–1894 CE) (Nkhotakota)

- Sultanate of Zanzibar (1856–1890/1964 CE)

- Sultanate of Hobyo (1880s–1888/1927 CE)

- Leqa Neqemte[81] (19th century CE)

- Leqa Qellem[81] (19th century CE)

- Uhehe Kingdom[82][83] (19th century–1898 CE) (Hehe people)

- Usangi Kingdom (19th century–?/1962 CE)

- Uvinza/Buvinza (19th century CE) (Vinza people)

- Nyamwezi Kingdoms:[84] (19th century CE) (Nyamwezi people)

- Unyanyembe

- Ulyankulu

- Usukuma[23]: 332–333 (NSM in Tanzania) (Sukuma people)

- Mirambo (1858–1895 CE)

- Sultanate of Biru/Girrifo[85][86] (?–early 20th century CE) (Bidu (woreda)) (Afar people#Aussa states)

West Africa

A non-exhaustive list of kingdoms and empires in West Africa that we have record of:

4th millennium BCE – 6th century CE

- Ghana Empire/Wagadu (350–1240/15th century CE) (Kaya Magan Cissé) (institution of kingship was very likely to exist in Mali at this time, and in West Africa well before, due to large tumuli)[87]

- Takrur Kingdom (6th century–1456/1526 CE)

7th century – 12th century CE

- Gao/Kaw Kaw Empire[88] (7th century–1430 CE) (Za dynasty)

- Bainuk kingdom[89] (7th century–13th century CE) (Bainuk people)

- Dô (pre-11th century–pre-18th century CE)

- Malel/Kiri/Mande[90]: 127–128 (pre-11th century–13th century CE)

- Méma Kingdom (8th century–1450 CE)

- Silla (pre-11th century–13th/14th century CE)

- Hausa Kingdoms

- Daura (700–1805/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria) ("mother city")[91]: 13 succeeded by Daura-Baure and Daure-Zango[92] (1825–1903 CE)

- Kingdom of Kano (999–1349 CE) succeeded by Sultanate of Kano (1350–1805 CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Gadawur Kingdom (?–15th century/present) (conquered by Kano)

- Rano (1001–1819/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Zazzau/Zaria (11th century–1808/1902/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Gobir (11th century–1803/? CE) (centre of Jihad of Usman dan Fodio)

- Biram (1100–1805/1991/? CE)

- Katsina[93]: 273–274 (1348–1807/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Maradi, Niger (19th century CE)

- Bastard states:

- Zamfara (11th century–1804 CE)

- Kwararafa (1500–1840 CE) (kingdom or tribal confederation) (Jukun people)

- Nupe/Kede[23]: 332–333 (1531–1835 CE) (NSM in Nigeria) split into East and West Nupe in civil war (1796–1805 CE)[92]

- Kebbi[93]: 277–278 (1516–1808/1902 CE)

- Yauri/Yawri

- Gwari

- Igodomigodo (900–1170 CE) (succeeded by Benin) (Ogiso monarchy and List of the Ogiso)

- Udo[94] (?–15th/16th century CE) (possibly Yoruba)[95]

- Igbo kingdoms: (Igbo people)

- Kingdom of Nri (948 – 1911/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria) (List of rulers of Nri) (Igbo–Ukwu)

- Nnewi Kingdom (1498–1904/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria) (List of Nnewi monarchs)

- Aguleri Kingdom

- Arochukwu and the Aro Confederacy[96] (1690–1902 CE): Arondizuogu, Ajalli, and Ndikelionwu

- Onitsha (NSM in Nigeria)

- Agbor (NSM in Nigeria) (Ika people)

- Aboh

- Oguta

- Eri Kingdom (Eri (king))

- Aoudaghost Kingdom (?–12th century/17th century CE)

- Maranda Kingdom[97]: 305 (10th century CE) (Ibn al–Faqih's account)

- Takedda Kingdom[98] (10th century–14th century CE)

- Tadmekka Kingdom[97]: 306 (10th century–14th century CE)

- Gajaaga/Galam Kingdom (1000–1858 CE)

- Yoruba Kingdoms:[99] (Oduduwa) (Yoruba Civil Wars and Kiriji War)

- Owo (1019–1893/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Ilesa/Ijesha (1150 CE–?/present) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Ila Yara (12th century–15th century CE) split in two

- Ife Empire (1200–1420 CE, ?–present) (NSM in Nigeria) (List of rulers of Ife) ("mother city")[91]: 13

- Ìsèdó (13th/14th century CE–?)

- Owu Kingdom (?–? CE)

- Ugbo Kingdom (NSM in Nigeria) (Emergence of the Ugbo)

- Oyo Empire (1300–1898/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria) (List of rulers of Oyo)

- Ijebu (1400–1892/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Ado Kingdom (15th century–1891 CE)

- Iwo (1415 CE–?/present)

- Ondo (1510–1899/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Dassa–Zoumé (1600–1889/present CE) (NSM in Benin) (List of rulers of Dassa)

- Lagos (1600–1862/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria) (Oba of Lagos)

- Ogbomosho (1659–?/present CE)

- Bussa (pre 1730–19th century CE) (Rulers of Bussa)

- Savè/Sabe (1738–1894/present CE) (NSM in Benin) (List of rulers of Sabe)

- Ketu/Ketou (1795–1880s/present CE) (NSM in Benin) (List of rulers of Ketu) (Amedzofe (history))

- Egbaland[92][100] (1829 CE–1914/present) (Abeokuta) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Alake/Ake (NSM in Nigeria) (List of Alakes of Egbaland)

- Oke Ona

- Gbagura

- Ijaiye (1836–1861 CE)

- Yewa (pre–1840s CE, 1890–1914 CE)

- Ibadan (?–1893/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Akure (?–?, 1818–1854/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Badagry (1821–1863 CE)

- Others: Igbomina (Ila Orangun), Offa, Idoani Confederacy, Ipokia, Isinkan, Agbowa–Ikosi, Osogbo and Ede

- Kingdom of Diarra/Jara/Zara/Diafunu (1076–1860 CE) (at times vassal of Ghana, Mali and Kaarta)

- Sosso Empire (1076–1235 CE) (at the same time as other Ghana successors such as Diarra, Yaresna, Ghiryu, and Sama)

- Namandirou (11th century–1460 CE)

- Bandial Kingdom (?–present)

- Kingdom of Benin (1170–1897/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria) (Oba of Benin)

- Mossi Kingdoms:[101]: 230–232 (used agnatic succession and hereditary elective monarchy)

- Wagadugu Empire (1182–1896/present CE) (NSM in Burkina Faso) (List of rulers of Wogodogo) preceded by Wubritenga[101]: 227

- Tenkodogo (1120 CE–?/present) (NSM in Burkina Faso) (List of rulers of Tenkodogo)

- Fada N'Gourma/Nungu (1204–1895/present CE) (NSM in Burkina Faso) (Gurma people) (List of rulers of Nungu)

- Zondoma/Rawatenga/Yatenga (pre 1333–late 19th century/present CE) (NSM in Burkina Faso) (List of rulers of Yatenga)

- Boussouma (NSM in Burkina Faso)

- Bilayanga

- Koala (1718 CE–?)

- Minor kingdoms (some of which constituted the Buricimba/Gulmanceba Empire):[102]: 178–180 Gurunsi, Bongandini, Con, Macakoali, Piela, (Ratenga, Zitenga),[101]: 227 Giti,[101]: 228 (Konkistenga, Yako, Téma, Mané, Kugupela, Kayao, Tatenga),[101]: 229 (Builsa, Busuma)[102]: 174

- Edem Kingdom (12th century CE–?/present) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Bonoman Kingdom (12th–19th century CE) (List of rulers of Bonoman)

13th century – 18th century CE

- Akpakip Oro (1200–1909 CE)

- Kingdom of Doma[92] (1233–1901 CE)

- Kingdom of Wuli (1235–1889 CE)

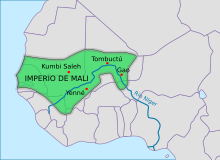

- Mali Empire[90]: 157–171 (1235–1670 CE) (Kouroukan Fouga) preceded by Manden/Kangaba (1050–1237 CE) (History of the Mali Empire) (Twelve Doors of Mali) (NSM in Mali)

- Mankessim Kingdom (1252–1844/present CE) (NSM in Ghana) (capital of First Fante Confederacy)

- Kombo Kingdom (1271–1875 CE) (Kombo Civil War (1850–1856))

- Waalo Kingdom (1287–1855 CE)

- Begho/Bron/Banda[103] (13th century–1680 CE) succeeded by Asante Empire

- Kingdom of Ugu (13th century–?/present) (split from Igodomigodo)

- Ahanta Kingdom (13th century–1656/19th century CE)

- Jolof Empire (13th/14th century–1549 CE) succeeded by Kingdom of Jolof (1549–1890 CE)

Jolof Empire in the 15th century - Kingdom/Imamate of Wala (1317 CE–?)

- Adansi Kingdom (14th century–18th century CE) (Adansi) (List of rulers of Adansi) constituent states seceded after Ashanti conquest, (all conquered by Denkyira in 1680s?):[104]: 212

- Akyem Abuakwa (pre-16th century CE–?) (NSM in Ghana) (List of rulers of Akyem Abuakwa)

- Akyem Kotoku (pre-16th century CE–?) (List of rulers of Akyem Kotoku)

- Akyem Bosome (pre-16th century CE–?) (List of rulers of Akyem Bosomoe)

- Kingdom of Sine (14th–19th century CE)

- Kingdom of Niani (14th century-late 19th century CE)

- Urhobo Kingdoms:[105] (14th century CE–?) (Urhobo people)

- Songhai Empire (14th century–1591 CE)

- Sonni dynasty (14th century–1493 CE)

- Askiya dynasty (1493–1591 CE) succeeded by Dendi Kingdom (1591–1901 CE)

- Massina Sultanate[92] (1400–1818 CE)

- Sultanate of Agadez (1404–1500 CE, 1591–1906/present CE) (NSM in Niger)

West Africa in 1625 CE - Kingdom of Dagbon (14th/15th century–1896/present CE) (NSM in Ghana) (List of kings of Dagbon)

- Kingdom of Daniski[92] (CE 1447–1806 CE) succeeded by Fika (1806–1899 CE) (Bolewa people)

- Mamprugu Kingdom[107] (1450 CE–?/present) (Mamprusi) (NSM in Burkina Faso)

- Brass kingdom[92] (1450–1885 CE)

- Kingdom of Bonny (1450–1885/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Warri Kingdom (1480 CE–?/present) (NSM of the Itsekiri people in Nigeria)

- Gonja Kingdom[108][109] (1495 CE–1713/present) (NSM in Ghana) (Yagbongwura) (Yagbum) (1892 Sack of Salaga) (Gonja people)

- Empire of Great Fulo (1513–1776 CE) succeeded by Imamate of Futa Toro (1776–1877 CE) (List of rulers of Futa Toro), all preceded by Futa Kingui (1464–1490 CE) and Dia Ogo dynasty[92] (850–1513 CE)

- Kingdom of Saloum (1494–1871/1969 CE)

- Kingdom of Baddibu[110][111] (pre–1861 CE) (Central Baddibu and Lower Baddibu in Gambia)

- Walata Kingdom (pre 15th century CE–?)

- Bariba kingdoms:[112][113][114]: 38 (pre–16th century, 1783–19th century CE) (Bariba people) (Borgu)

- Kingdom of Niumi/Barra (15th century–1897/1911 CE) (Barra War)

- Kasa/Kasanga Kingdom (15th century–1830 CE)

- Nanumba Kingdom[115] (15th century CE–?) (Nanumba people) (Bimbilla)

- Asebu Kingdom (15th century CE–?) (Asebu Amanfi)

- Simpa/Fetu/Winneba Kingdom[116]: 337 (15th century–1720/? CE) (Efutu people) (Winneba) (King Ghartey IV)

- Eguafo/Aguafo Kingdom[117][116]: 337 (15th century CE–?) (Fante people)

West Africa circa 1875 - Okrika/Wakirike Kingdom (?–1913 CE)

- Agona/Denkyira Kingdom (1500–1701 CE) (List of rulers of Denkyira)

- Akim kingdom[92] (c. 1500–c. 1899)

- Kingdom of Koya/Temne/Quoja (1505–1896 CE)

- Igala Kingdom (1507–1900/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Kingdom of Gã (1510 CE–?/present) (Gã Mantse) (King Okaikoi and Dode Akaabi)

- Yamta/Biu Kingdom (1535–1900 CE)

- Kaabu Empire (1537–1867 CE)

- Kingdom of Cayor (1549–1879 CE) (Lat Soukabé Ngoné Fall united Cayor with Baol from 1697 to 1720)

- Kingdom of Baol (1555–1874 CE) (Lat Soukabé Ngoné Fall united Cayor with Baol from 1697 to 1720)

- Akwamu Kingdom (1560–1733/present CE) (NSM in Ghana) (List of rulers of Akwamu and Twifo) preceded by Twifo Kingdom (1480–1560 CE)

- Emirate of Tagant (1580–19th century CE) (NSM in Mauritania)

- Pashalik of Timbuktu[118] (1591–1833 CE) (Arma people)

- Djenné, Gao and either Bamba, Mopti or Bamba, Gao Region were very autonomous with only nominal Timbuktu rule

- Tougana Kingdom (1591 CE–?) and Gorouol Kingdom

- Kingdom of Bissau (pre 16th century–1915/present CE) (NSM in Guinea–Bissau)

- Kingdom of the Sapes[119][120] (CE pre–16th century) (mentioned in Mane people) (exonym, not sure of alternative/native name as they were multiethnic) succeeded by: (History of Sierra Leone)

- Baté Empire (16th century–19th century CE)

- Idoma Kingdom[121] (?–? CE) (Idoma people)

- Huba/Kilba Kingdom[122] (16th century–1904 CE) (Kilba people)

- Wassa kingdoms[123]: 33 (16th/17th century–?) (Wasa people)

- Kwahu[123]: 33 (16th/17th century–?) (Kwahu)

- Biafada Kingdoms: (Biafada people)

- Guinala/Quinala (pre 15th century CE–?) (vassal of Kaabu)

- Biguba

- Bissege (Bissagos Islands?)

- Kingdom of Sukur/Margi (16th century CE–?) (Margi people)

- Kingdom of Dwaben/Dwabeng (1600/1874 CE–?) (List of rulers of Dwaben)

- Nembe Kingdom (1639–1884/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Emirate of Trarza (1640–1902/present CE) (NSM in Mauritania)

- Emirate of Brakna[124]: 142 (17th century–19th century CE) (mentioned in Trarza)

- Kénédougou Kingdom (1650–1898 CE)

- Gyaman/Jamang/Abron Kingdom (1650–1888/1897 CE) (List of rulers of Gyaman)

- Kingdom of Kaarta (1610–1870/1904 CE)

- Asante/Ashanti Empire[23]: 332–333 (1680–1896/1902 CE, 1935–1957/present CE) (NSM in Ghana) (Golden Stool) (List of rulers of Asante)

- Imamate of Nasr ad–Din (1673–1674 CE) (Char Bouba/Mauritanian Thirty Years' War)

- Khasso/Xaaso Kingdom (1681–1880 CE)

Fula jihad circa 1830 - Bundu Kingdom (1690–1858 CE)

- Sefwi Kingdoms:[104]: 211 (pre 17th century CE–?) (Sefwi people)

- Assini

- Abripiquem

- Ankobra

- Nzima Kingdom[104]: 213 (18th century CE–?) (formed by combining Abripiquem, Ankobra and Jomoro) (Nzema people)

- Lafia Emirate (17th century CE–?/present)

- Aowin Kingdom (?–?/present) (NSM in Ghana)

- Kalabari Kingdom (pre 1699–1900/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Gbe speaking peoples;

- Aja/Adja Kingdoms

- Tado (a primary dispersal point for Gbe speaking groups)

- Ewe Kingdoms:[125][104]: 212 (pre–1710/? CE) (Ewe people) (conquered by Akwamu)

- Notsé/Notsie/Nuadja Kingdom (15th century CE–?/present) (NSM in Togo) (Togbe Agorkoli)

- Anlo (List of rulers of Anlo) (Anlo Ewe)

- Peki (List of rulers of Peki)

- Kpando

- Kingdom of Agwe (1812–1895/present CE)

- Ho

- Fon and closely related Kingdoms

- Kingdom of Ardra/Allada (1440–1894/present CE) (NSM in Benin) (List of rulers of Allada)

- Kingdom of Whydah/Ouidah (1580–1727/present CE) (NSM in Benin) (List of rulers of Whydah)

- Kingdom of Dahomey (1600–1900/present CE) (NSM in Benin)

- Agaja dynasty[126] (1600–1818 CE)

- Ghezo dynasty (1818–1900 CE)

- Hogbonu Kingdom[127] (17th century–1863/1908/present CE) (NSM in Benin) (List of rulers of Hogbonu (Porto–Novo))

- Kingdom of Savalou kingdom of the Mahi (1557–1769/1894/present CE) (NSM in Benin)

- Peda/Popo kingdom/s:

- Grand Popo/Pla/Hulagan Kingdom (pre 17th century CE–?) and Djanglanmey

- Little Popo/Gen/Glidji/Aného Kingdom (1750–1883/1885 CE) (NSM in Togo)

- Aghwey/Agoué (19th century CE) (NSM in Benin)

- Wémè Kingdom[128] (17th century–18th century CE) (Ouémé Department of Benin)

- Aja/Adja Kingdoms

- Asen (17th century CE)

- Kingdom of Dubréka (17th century–19th century CE)

- Imamate of Futa Jallon (1700–1881/1912 CE) (Fugumba)

- Keana[92] (1700–1900 CE)

- Kong Empire (1710–1894 CE)

- Kingdom of Baule[129][130] (1710–1893/present CE) (Baoulé people) (NSM in Côte d'Ivoire)

- Bamana Empire of Segu/Segou (1600–1861 CE)

- Gwiriko Kingdom (1714–1890/1915 CE)

- Bethio Principality (1724 CE–?/present) (NSM in Senegal)

- Akropong–Akuapem Kingdom (1730 CE–?/present) (NSM in Ghana) (List of rulers of Akuapem)

- Gumel[92] (1749–1903 CE)

- Dosso Kingdom (1750–1849 CE, 1856–1898/present CE) (NSM in Niger)

- Keffi[92] (1750–1802/1902 CE)

- Lafia Kingdom[92] (1780 CE–1873/1900/present)

- Akwa Akpa (1786–1896/present CE)(NSM in Nigeria)

- Lebou Republic[131] (1790–1857/present CE) (Lebu people)

- Kingdom of Jakin[132][133]: 21 (pre-18th century–? CE)

- Anyi kingdoms:[104]: 212–213 (18th century–19th century CE) (Anyi people)

- Solima Kingdom[134][124]: 148 (18th century–1884 CE) (Yalunka people)

- Kingdom of Apollonia[135] (18th century–?)

- Kunaari (18th century–19th century CE)

- Kotokolia (18th century CE–?/present) (NSM in Togo)

Sokoto Caliphate 19th century - Sankaran Kingdom[124]: 148–149 (18th century CE–?) (referred to in Fugumba)

- Mahi kingdoms: (18th century–19th century CE) (Mahi people)

19th century CE – present

- Manya Krobo[138] (?–19th century CE) (List of rulers of Manya Krobo)

- Adrar[92] (1800–1909 CE) (Atar, Mauritania)

- Sokoto Caliphate (1804–1904/present CE) (NSM in Nigeria) (List of sultans of Sokoto) (had many emirates as vassals, which continue to exist to the present day as NSMs) (Fula jihads)

- Potiskum Emirate (1809–1901 CE)

- Massina Empire (1818–1862 CE)

- Emirate of Say (1825–? CE)

- Bedde kingdom[92] (1825–1902 CE) (Bade language)

- Aku kingdom[139][92] (1826–1880 CE) (Aku people)

- Jere/Qeko Kingdom (1840 CE–?/present) (NSM in Malawi and Zambia) (List of rulers of Jere)

- Kabadougou Kingdom (1848–1898/1980 CE)

- Toucouleur Empire (1852–1893 CE)

- Zabarma Emirate (1860–1897 CE)

- Fuladu Kingdom[140] (1867–1903/present CE) (NSM in the Gambia)

- Wassoulou Empire (1878–1898 CE) preceded by Wasulu (mid 17th century CE–?)

- Dubreka Kingdom[141] (pre–1885/1906 CE)

- Solimana (19th century CE)

- Kissi Kingdom (19th century CE) (Kissi Kaba Keita)

- Kiang Kingdom (19th century CE)

- Jimara Kingdom[140][142] (19th century CE)

- Tomani Kingdom[140][142] (19th century CE)

- Kantora Kingdom[140][142] (19th century CE)

- Niamina Kingdom[143][142] (19th century CE)

- Foni Kingdom[143][142] (19th century CE)

- Eropina Kingdom[142] (19th century CE)

- Opobo (19th century CE) (Jaja of Opobo)

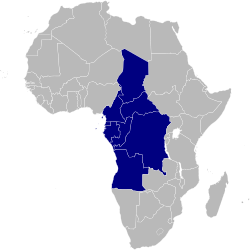

Central Africa

A non-exhaustive list of kingdoms and empires in Central Africa that we have record of:

7th century – 12th century CE

- Kanem Empire[144] (692–1380 CE) succeeded by Bornu Empire[145] (1380–1893 CE) (NSM in Nigeria)

- Duguwa/Zaghawa dynasty (700–1085 CE)

- Sayfawa dynasty (1085–1846 CE) succeeded by Rabih az–Zubayr

- Buffer states against the Tuareg: Damagram, Muniyo, Machina, Gaskeru, Tunbi[145]: 511

- Sao city-states[146] (1100/1400–15th century CE)

- Seven Kingdoms of Kongo dia Nlaza (pre 13th century-16th century CE) included the kingdoms of Mbata, Mpangu, and Nsundi[147]

- Vungu (pre 13th century–?)

- Mpemba[148] (pre 13th century-14th century) included the kingdoms of Mpemba Kasi and Vunda

- Kakongo (pre 13th century–1885 CE)

- Ngoyo (pre 13th century–1885 CE)

- Kibunga[148]: 29 (?–14th century CE)

13th century – 18th century CE

- Kingdom of Ndongo/Ngola (1358–1671/1909/present CE) (NSM in Angola) (List of Ngolas of Ndongo)

- Kingdom of Kongo (1390–1678 CE, 1691–1857/1914 CE, 1915–1975/present CE) (NSM in Angola)

- Kongo Civil War: (1665–1709 CE) led to Kongo fracturing into smaller kingdoms, to be later reunited by Pedro IV of Kongo:

- Kibangu (Manuel I of Kibangu)

- Lemba (João II of Lemba)

- Nsonso/Nkondo (Afonso II of Kongo and Nkondo) (assuming Nsonso/Sonso and Nkondo are the same)

- Mbamba Lovata (Manuel II of Kongo)

- Kongo Civil War: (1665–1709 CE) led to Kongo fracturing into smaller kingdoms, to be later reunited by Pedro IV of Kongo:

- Anziku/Tio/Teke Kingdom[149][150]: ix (14th century–1880)

- Tikar Fondoms:[151] (1390/pre 18th century CE–?/present) (Tikar people) (preceded by Nganha and the Mbum people (Mbum language))

- Tinkala

- Bamkin

- Ngambè–Tikar

- First wave:

- Bamum[152] (1390–1884/present CE) (NSM in Cameroon) (List of rulers of the Bamum)

- Nditam/Bandam

- Ngoumé

- Gâ (not to be confused with Ga–Adangbe)

- Nso (NSM in Cameroon)

- Second wave:

- Kong (not Kong Empire)

- Kom[153] (NSM in Cameroon)

- Ndu (Second degree NSM in Cameroon)

- Bankim

- Bamileke Fondoms: (pre 14th century CE–?) (over 100 in total)

- Luba Empire[154] (14th/15th/16th century–1885/present CE) (NSM in Democratic Republic of the Congo) (List of rulers of Luba) (Luba-Katanga language)

- Mwene Muji[155][150]: ix (c. 1400–early 20th century CE)

- Kotoko kingdom (15th century–19th century CE) vassals:

- Sultanate of Yao[156] (17th century–1909 CE) (Bilala people) (Yao)

- Nsanga[148]: 30 (?–15th century CE)

- Masinga[148]: 30 (?–15th century CE)

- Wembo[148]: 31 (?–15th/16th century CE)

- Wandu[148]: 31 (?–15th century CE)

- Ibom/Mbot Abasi Kingdom (Second degree NSM in Cameroon) (Aro–Ibibio Wars) preceded by Akwa Akpa (Ibibio) (not Akwa Akpa (Efik))

- Dembos[150]: ix (pre-1550–?) (confederation composed of 15 states)

- Kisama[150]: ix (pre-1550–?)

- Suku[154][150]: ix (pre-1550–?) (Suku people)

- Kingdom of Matamba (pre-1550–1744 CE)

- Nsonso (pre-1550–?)

- Okango[150]: ix (pre-1550–?)

- Mandara Kingdom (1500–1893/present CE) (NSM in Cameroon)

- Kasanze Kingdom (1500–1648 CE)

- Mbunda Kingdom (1500–1917/present CE) (NSM in Angola) (Rulers of Mbundaland)

- Sultanate of Bagirmi (1513–1899/present CE) (NSM in Chad) (List of rulers of Bagirmi)

- Kingdom of Bandjoun/Baleng (1545 CE–?/present) (NSM in Cameroon)

- Kingdom of Loango (1550–1883/present CE) (NSM in Republic of the Congo) (Nzari)

- Mutombo Mukulu[157]: 120 (pre-16th century–? CE) (buffer state between Luba and Lunda)

- Duala Kingdom[158][159] (16th century–1879 CE) (Duala people) (Douala) (Monneba) (List of rulers of the Duala)

- Nzakara Kingdom[160][161]: 560 [162]: 203 (16th century–? CE) (Nzakara language) (Ngbandi people)

- Kalundwe[154]: 589–599 (?–? CE)

- Kalonja[161]: 589 (?–? CE)

- Kanyok (?–?, 1780–1810/? CE)

- Luvale kingdom[163] (?–? CE)

- Humbe Kingdom[161]: 570 (16th century CE–?) (Nyanyeka)

- Muzumbu a Kalungu[164] (16th century CE–?)

- Libolo kingdom[165] (early 16th century–?) (Mbondo broke away in the 16th century)[165]

Kingdoms in Angola circa 1760 CE - Ovimbundo Kingdoms:[166] (Ovimbundu) (missing one)

- Kulembe/Kalembe ka Njanja[167][168] (16th century CE–?) (near Libolo)[161]: 570

- Bailundo (1700–1770/present CE) (NSM in Angola)

- Viye/Bie (1700 CE–?/present) (NSM in Angola)

- Wambu/Huambo/Hambo/Huamba (NSM in Angola)

- Ciyaka/Quiyaca/Quiaca

- Ngalangi/Galangue

- Civula/Quibula

- Ndulu/Andulo/Ondulo/Ondura

- Cingolo/Quingolo (?–1770 CE/?)

- Kalukembe/Caluqembe/Caluguembe/Caluqueme (pre 1740 CE–?)

- Sambu

- Ekekete/Quiquete

- Kakonda/Cilombo–conoma/Caconda/Quilombo

- Citata/Quitata

- Benguela Kingdom[169] (16th century–1615/present CE)

- Kingdom of Bandjoun (16th century–1926 CE)

- Kasanje Kingdom (1620–1910/present CE) (NSM in Angola) preceded by Imbangala

- Kuba Kingdom (1625–1884/present CE) (NSM in Democratic Republic of the Congo)

- Kingdom of Matamba (1631–1744 CE)

- Wadai Empire (1635–1912/present CE) (NSM in Chad) (List of rulers of Wadai)

- Dar Runga as a vassal

- Soyo Kingdom (1650 CE–?)

- Empire of Lunda[154] (1665–1887/present CE) (NSM in Democratic Republic of the Congo) preceded by Rund Kingdom[154]

- Bashi Kingdom (pre 17th century CE–?)

- Kingdom of Mbwila (pre 17th century CE–?) (generally maintained independence by playing Portuguese Angola and Kongo off of one another)

- Kingdom of Bouna (17th century CE–?)

- Guiziga Bui Marva[170]: 107–110 (17th century–1795 CE)

- Bemba/Buddu kingdom[23]: 332–333 (17th century CE–?/present) (Bemba people) (NSM in Zambia)

- Yaka Kingdom[171] (17th century–19th century CE) (Yaka people)

- Boma Kingdom/Ibar (17th century–19th century CE)

- Bozanga Kingdom[155][172] (17th century–? CE)

- Zaghawa kingdoms:[173]: 308 (17th century–18th century/?) (Zaghawa people)

- Pende kingdom[174][155] (?–? CE) (Pende people)

- Bolia Kingdom[175] (18th century CE–?)

- Kingdom of Orungu (1700–1873/1927/present CE) (NSM in Gabon) (List of rulers of Orungu)

- Sultanate of Damagaram (1731–1899 CE) (NSM of Niger) (buffer state between Kanem-Bornu and the Tuareg)

- Kazembe Kingdom (1740–1894/present CE) (NSM in Zambia) (Eastern Lunda)

- Mangbetu kingdom[176] (1750–1895 CE) (Mangbetu people)

- Fondom of Bafut (?–1907/present CE) (NSM in Cameroon)

- Mankon Fondom (1799–1901/present CE) (NSM in Cameroon)

- Bangassou Sultanate (pre 18th century CE–?/present) (NSM in Central African Republic)

- Azande Kingdom (18th century CE–1905/present) (NSM in South Sudan)

19th century CE – present

- Zande sultanates:[177] (19th century CE)

- Sultanate of Zemio (1823–?/1923 CE)

- Sultanate of Rafaï

- Dar al Kuti Sultanate (1830–1911 CE) (NSM in Central African Republic)

- Yeke Kingdom (1856–1891 CE)

- Sultanate of Utetera (1860–1887 CE) (Tippu Tip)

- Kingdom of Rabih az–Zubayr (1880s–1900 CE) (conquered the Bornu Empire)

- Lusinga's kingdom[178] (1880s CE)

- Tupuri Kingdom of Doré (19th century CE) (Wang Doré)

- South Kasai (1960–1962 CE) (monarchy proclaimed in 1961)

- Central African Empire (1976–1979 CE)

Southern Africa

A non-exhaustive list of kingdoms and empires in Southern Africa that we have record of:

7th century – 12th century CE

- Mapela (1055–1400 CE)

13th century – 18th century CE

- Kingdom of Mapungubwe (1220–1300 CE) preceded by Leopard's Kopje and K2

Map of trade centres and routes in precolonial Zimbabwe. - Kingdom of Great Zimbabwe[180] (11th/13th century–16th/17th century CE)

- Kingdom of Tonge[181][182] (?–? CE) (Manyikeni)

- Thulamela[183] (13th century–17th century CE)

- Nambya state[184] (14th century–? CE) (Nambya people)

- Empire of Mutapa/Mwenemutapa[185] (1330/15th century–1888 CE)

- Kingdom of Butua (1450–1683 CE) (Torwa dynasty)

- Rozwi Empire[186] (1480–1866 CE)

- Empire of Maravi[187] (1480–1891/present CE) (NSM in Zambia)

- Kingdom of Barue (15th century–? CE)

- Teve kingdom/Uteve/Kiteve[182] (15th century–?) (possibly preceded by a larger kingdom from the 10th century)[188]

- Madanda[189][182] (?–1820s CE)

- Manyika kingdom/Manica[189][190]: 168 (pre-16th century–19th century CE) (Manyika people)

- Ngulube Kingdoms:[187]: 300–301 (16th century CE–?)

- Ulambya Kingdom[191]: 55–66 (Lambya people)

- Ngonde Kingdom[192][193] (1600 CE–?) (NSM in Malawi) (southern Nyakyusa people)

- Chifungwe Kingdom (Fungwe people in Mafinga District)[187]: 309

- Sukwa Kingdom[193]: 135 (Sukwa people)

- others: (Kameme, Misuku, Mwaphoka Mwambele, Kanyenda, Kabunduli, Kaluluma, and Chulu)[187]: 309

- Lozi Empire[194][92] (16th century–1838, 1864–1899 CE) (NSM in Zambia) (Lozi people)

- Ovambo kingdoms:[195][196] (16th century–late 19th/early 20th century CE) (Ovambo people)

- Ondonga (1650 CE–?/present) (NSM in Namibia) (split into Oshitambi and Onamayongo during civil war (1885–1908 CE))[195]: 146 (List of Ondonga kings)

- Uukwanyama[197] (NSM in Namibia) (Battle of the Cunene) (Mandume ya Ndemufayo)

- Ongandjera (?–?/present) (NSM in Namibia)

- Uukwaluudhi (pre 1850 CE–?/present) (NSM in Namibia) (List of Uukwaluudhi kings)

- Uukwambi (NSM in Namibia)

- Uukolonkadhi/Uukolonkathi (NSM in Namibia)

- Ombadja (NSM in Namibia) (Mbadja people)

- Evale[195]: 124–130

- Ombalantu[195]: 135–137 (NSM in Namibia)

- May not be Ovambo or kingdoms: Eunda/Ehanda, Ombwenge (short–lived invasion of Ondonga),[195]: 116 (Oukwanka/Onkwanka, Okafima, Oukumbi/Onkumbi, Eshinga, Okavango),[195]: 122

- Southern Ndebele Kingdoms: (Southern Ndebele people)

- Ndebele (16th century CE–?) split into:

- Manala (NSM in South Africa)

- Ndzundza (NSM in South Africa)

- Ndebele (16th century CE–?) split into:

- Tembe kingdom[183][198][199] (16th century–1885 CE) (Maputsu split away c. 1800 to form his own kingdom)[198] (Tembe people)

- Nyaka kingdom[198][199] (16th century–? CE)

- Belingane kingdom[200][198] (16th century–? CE)

1747 British map of Mutapa and surrounding kingdoms - Mbara kingdom[201][202] (?–? CE)

- Mabhudu Kingdom[203][204] (?–? CE)

- Singo state[205][206][183][207] (17th century–late 18th century CE) succeeded by several Venda kingdoms

- Maungwe (17th century–1889/1896 CE)

- Swaziland/Eswatini (1745 CE–present) (SM of Eswatini) (List of monarchs of Eswatini)

- Tswana kingdoms:[208] (dynasties going back to the 15th century)[92] (Tswana people) (Kweneng' Ruins)

- Ngwaketse (1750–1885/present CE) (NSM in Botswana)

- Barolong (1760–1885/present CE) (NSM in Botswana)

- Ngwato (1780–1885/present CE) (NSM in Botswana)

- Batlôkwa (1780–1885/present CE) (NSM in Botswana and South Africa) (List of rulers of Tlôkwa)

- Batawana (1795–1885/present CE) (NSM in Botswana)

- Batlhaping (18th century CE–?)

- Balete (pre 1805–1885/present CE) (NSM in Botswana) (List of rulers of Lete (Malete))

- Xhosa Kingdom[209][210] (1775–1879/present CE) (NSM in South Africa) (List of Xhosa kings)

- Thembu kingdom[210] (?–1885 CE/present) (NSM in South Africa)

- Mpondomise kingdom[210] (?–? CE) (AmaMpondomise)

- Ndwandwe Kingdom (1780–1819 CE)

- Hlubi Kingdom (c. 1780 CE–1800/1848/present) (NSM in South Africa) (c. 1800 split into factions and incorporated into Cape Colony, except for Langalibalele's kingdom, which later migrated into British Natal c. 1848)[211]

- Mpondo kingdom[212] (1780 CE–1867/present) (Mpondo people) (NSM in South Africa)

- Kavango kingdoms:[213][214] (Kavango people)

- Mthethwa Empire (18th century–1820 CE)

- Nkhamanga Kingdom (18th century–? CE)

- Marota/Pedi Kingdom[215][183] (late 18th century–1882 CE, 1885 CE–present) (NSM in South Africa) (Pedi people) (Mampuru II)

19th century CE – present

- Balobedu Kingdom[199] (1800 CE–?/present) (Lobedu people) (NSM in South Africa) (Rain Queen)

- Cornelius Kok I's land[92] (1813–1857 CE)

- Ngoni Kingdom (1815–1857/present CE)

- Zulu Kingdom[216] (1816–1897/present CE) (NSM in South Africa)

- Lesotho (1822 CE–present) (SM of Lesotho) (List of monarchs of Lesotho)

- Gaza Empire (1824–1895 CE)

- Adam Kok's land[92] (1826–1861 CE)

- Nxaba's kingdom[217][218] (?–1837 CE)

- Kololo Kingdom[219] (1838–1864 CE) (conquered the Lozi Empire)[92] (Kololo people)

- Kingdom of Mthwakazi/Ndebele (1840–1895 CE) (Northern Ndebele people)

See also

- History of Africa

- List of kingdoms and royal dynasties

- List of former sovereign states

- List of Muslim states and dynasties

- List of current non–sovereign African monarchs

- List of Nigerian traditional states

- List of fictional African countries

- Monarchies in Africa

- Chiefdom

- Confederation

- List of confederations

- Queen mother (Africa)

- Category:Lists of rulers in Africa and Category:Lists of monarchs in Africa

- Category:Archaeological sites in Africa

- Category:Archaeological sites in Gran Canaria

Notes

- ^ Origin myths serve multiple purposes, helping to define a group's identity and forge sociocultural alliances, and provide the fulcrum on which a group's religious ideology rests.[5] Dynastic oral traditions often have the king as a stranger, situated above or beyond society. They are considered "a source of order, fertility and well-being", but also "volatile, capricious and potentially dangerous."

Further reading

- General History of Africa (1981–present)

- Cambridge History of Africa (1975–1986)

- Shillington, Kevin (2012). History of Africa. Internet Archive. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire : New York, NY : Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-30847-3.

- Parker, John (2023). Great Kingdoms of Africa. Univ of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-39567-1.

- Stewart, John (2024). African States and Rulers, 3d ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1707-7.

- Aderinto, Saheed (2017). African Kingdoms: An Encyclopedia of Empires and Civilizations. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-61069-580-0.

- Shillington, Kevin, ed. (2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9780203483862. ISBN 978-1-135-45670-2. Archived from the original on 2024-04-11. Retrieved 2025-01-13.

- Ayittey, George (2006). Indigenous African Institutions: 2nd Edition. Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-4003-1.

References

- ^ "Dictionary.com | Kingdom". Dictionary.com. Retrieved 2024-10-25.

- ^ Howe, Stephen (2002). Empire: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. p. 30. ISBN 978-0-19-280223-1.

- ^ Southall, Aidan (1974). "State Formation in Africa". Annual Review of Anthropology. 3: 153–165. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.03.100174.001101. JSTOR 2949286.

- ^ González-Ruibal, Alfredo (2024-11-23). "Traditions of Equality: The Archaeology of Egalitarianism and Egalitarian Behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa (First and Second Millennium CE)". Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. 32 (1): 6. doi:10.1007/s10816-024-09678-1. hdl:10261/395172. ISSN 1573-7764.

- ^ Aderinto, Saheed (201). African Kingdoms: An Encyclopedia of Empires and Civilizations. p. xix.

- ^ a b Parker, John (2023-03-21), "Introduction: Kings, Kingship and Kingdoms in African history", Great Kingdoms of Africa, University of California Press, pp. 11–28, doi:10.1525/9780520395688-002, ISBN 978-0-520-39568-8, retrieved 2024-12-01

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Dalziel, Nigel; MacKenzie, John M, eds. (2016). "African kingdoms and empires". The Encyclopedia of Empire (1 ed.). Wiley. pp. 1–2. doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe378. ISBN 978-1-118-44064-3.

- ^ Kyed, Helene Maria; Buur, Lars (2007), Buur, Lars; Kyed, Helene Maria (eds.), "Introduction: Traditional Authority and Democratization in Africa", State Recognition and Democratization in Sub-Saharan Africa: A New Dawn for Traditional Authorities?, New York: Palgrave Macmillan US, pp. 1–28, doi:10.1057/9780230609716_1, ISBN 978-0-230-60971-6, retrieved 2024-12-07

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Thies, Cameron G. (2009). "National Design and State Building in Sub-Saharan Africa". World Politics. 61 (4): 623–669. doi:10.1017/S0043887109990086. ISSN 1086-3338.

- ^ Florêncio, Fernando (2017). No Reino da Toupeira: Autoridades Tradicionais do M'balundu e o Estado Angolano [In the Mole Kingdom: Traditional M'balundu Authorities and the Angolan State]. ebook'IS (in Portuguese). Lisboa: Centro de Estudos Internacionais. pp. 79–175. ISBN 978-989-8862-32-7. Archived from the original on 2021-07-28. Retrieved 2022-08-21.

- ^ "Chad: protests over Ouaddai sultanate autonomy". CounterVortex. 2022-01-31. Archived from the original on 2023-06-19. Retrieved 2023-06-21.

- ^ "Tanzania chiefs and monarchs". The African Royal Families. 13 June 2023. Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ Kasfir, Nelson (2019). "The restoration of the Buganda Kingdom Government 1986–2014: culture, contingencies, constraints". The Journal of Modern African Studies. 57 (4): 519–540. doi:10.1017/S0022278X1900048X. ISSN 0022-278X.

- ^ Mfonobong Nsehe. "The 5 Richest Kings In Africa". Forbes. p. 2. Archived from the original on 7 July 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2016.

- ^ Middleton, John (2015). World Monarchies and Dynasties. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-45158-7.

- ^ a b Awasom, Nicodemus Fru (2024), Awasom, Nicodemus Fru; Dlamini, Hlengiwe Portia (eds.), "Trends Towards Presidential Monarchism in Postindependence Africa", The Making, Unmaking and Remaking of Africa's Independence and Post-Independence Constitutions, Philosophy and Politics – Critical Explorations, vol. 31, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 11–35, doi:10.1007/978-3-031-66808-1_2, ISBN 978-3-031-66808-1, retrieved 2024-12-14

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Brownlee, J. (2007). "Hereditary Succession in Modern Autocracies". World Politics. 59 (4). Cambridge University Press: 595–628. doi:10.1353/wp.2008.0002. S2CID 154483430. Archived from the original on 2024-03-01. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ a b Mengara, Daniel (2020). "The Making of a Monarchical Republic: The Undoing of Presidential Term Limits in Gabon Under Omar Bongo". The Politics of Challenging Presidential Term Limits in Africa. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 65–104. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-40810-7_3. ISBN 978-3-030-40809-1. S2CID 216244948. Archived from the original on 2024-03-01. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Osei, Anja (2018). "Like father, like son? Power and influence across two Gnassingbé presidencies in Togo". Democratization. 25 (8): 1460–1480. doi:10.1080/13510347.2018.1483916. Archived from the original on 2024-01-05. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Bezabeh, Samson (2023). Djibouti: A political history (PDF). Lynne Rienner. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-10-14. Retrieved 2024-03-14.

- ^ Schmidt, Peter Ridgway (2006). Historical Archaeology in Africa: Representation, Social Memory, and Oral Traditions. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 978-0-7591-0965-0.

- ^ Odhiambo, E. S. Atieno (2004). "The Usages of the past: African historiographies since independence". African Research and Documentation. 96: 3–61. doi:10.1017/S0305862X00014369. ISSN 0305-862X.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Vansina, Jan (1962). "A Comparison of African Kingdoms". Africa: Journal of the International African Institute. 33 (4). Cambridge University Press: 332–333. doi:10.2307/1157437. JSTOR 1157437. S2CID 143572050. Archived from the original on 2023-03-30. Retrieved 2024-03-09.

- ^ Wilkinson, Toby (2010). "The Early Dynastic Period". A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-2006-0. Archived from the original on 2024-03-21. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Baud, Michel (2010). "The Old Kingdom". A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-2006-0. Archived from the original on 2024-03-21. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Willems, Harco (2010). "The Middle Kingdom: The Twelfth Dynasty". A Companion to Ancient Egypt. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4443-2006-0. Archived from the original on 2024-03-21. Retrieved 2024-03-21.

- ^ Jakobielski, Stefan (1988). "Christian Nubia at the height of its civilisation". General History of Africa: Volume 3 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. p. 194. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-22. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ a b Mahjoubi, Ammar; Salama, Pierre (1981). "The Roman and post-Roman period in North Africa". General History of Africa: Volume 2. UNESCO Publishing. Archived from the original on 2023-04-06. Retrieved 2024-02-21.

- ^ Steward., Evans (1996). The age of Justinian : the circumstances of imperial power. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-02209-6. OCLC 797873981.

- ^ a b c Kapteijns, Lidwien (1983). "Dār Silā, the Sultanate in Precolonial Times, 1870–1916 (Le sultanat du Dār Silā à l'époque précoloniale, 1870–1916)". Cahiers d'Études Africaines. 23 (92): 447–470. doi:10.3406/cea.1983.2239. JSTOR 4391880. Archived from the original on 2024-03-15. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Talbi, Mohamed (1988). "The independence of the Maghrib". General History of Africa: Volume 3 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. p. 251. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-22. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ Saidi, O. (1984). "The unification of the Maghreb under the Alhomads". General History of Africa: Volume 4 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. pp. 45–53. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ Hrbek, Ivan (1984). "The disintrigation of the political unity of the Maghreb". General History of Africa: Volume 4 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. p. 84. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ a b c Kapteijns, Lidwien (1983). "The Emergence of a Sudanic State: Dar Masalit, 1874–1905". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 16 (4). Boston University African Studies Center: 601–613. doi:10.2307/218268. JSTOR 218268. Archived from the original on 2024-02-12. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Stuart (1991). Aksum: An African Civilisation of Late Antiquity (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-01-19. Retrieved 2024-03-09.

- ^ LaViolette, Adria; Fleisher, Jeffrey (2009). "The Urban History of a Rural Place: Swahili Archaeology on Pemba Island, Tanzania, 700–1500 AD". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 42 (3). Boston University African Studies Center: 433–455. JSTOR 40646777. Archived from the original on 2024-03-15. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ a b Braukämper, Ulrich (1977). "Islamic Principalities in Southeast Ethiopia Between the Thirteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (part 1)". Ethiopianist Notes. 1 (1): 17–56. ISSN 1063-2751. JSTOR 42731359.

- ^ Smidt, Wolbert (2011). "Preliminary Report on an Ethnohistorical Research Among the Ch'aré People, a Hidden Ethnic Splinter Group in Western Tigray" (PDF). Northeast African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities. 1: 115–116. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ a b Aalen, Lovise (2011). The Politics of Ethnicity in Ethiopia: Actors, Power and Mobilisation under Ethnic Federalism. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20937-4.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard (1997). The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century. The Red Sea Press. ISBN 978-0-932415-19-6.

- ^ Buchanan, Carole Ann (1974). The Kitara complex: the historical tradition of western Uganda to the 16th century (PDF) (Thesis). Indiana University. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-05-21. Retrieved 2024-02-20.

- ^ Umair Mirza (2005). Encyclopedia of African History And Culture, Volume 2.

- ^ a b c Braukämper, Ulrich (1977). "Islamic Principalities in Southeast Ethiopia Between the Thirteenth and Sixteenth Centuries (part Ii)". Ethiopianist Notes. 1 (2): 1–43. ISSN 1063-2751. JSTOR 42731322.

- ^ a b c d e Ogot, Bethwell Allan (1984). "The Great Lakes region". General History of Africa: Volume 4 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ a b Ochieng, William (1992). "The interior of East Africa: The peoples of Kenya and Tanzania, 1500–1800". General History of Africa: Volume 5. UNESCO Publishing. Archived from the original on 2024-03-03. Retrieved 2024-03-03.

- ^ a b Haberland, Eike (1992). "The Horn of Africa". General History of Africa: Volume 5. UNESCO Publishing. Archived from the original on 2024-03-03. Retrieved 2024-03-03.

- ^ a b Dramani-Issifou, Zakari (1988). "Stages in the development of Islam and its dissemination in Africa". General History of Africa: Volume 3 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-22. Retrieved 2024-02-22.

- ^ Deribew, Kiros Tsegay; Mihretu, Yared; Abreha, Girmay; Gemeda, Dessalegn Obsi (2022-10-01). "Spatial analysis of potential ecological sites in the northeastern parts of Ethiopia using multi-criteria decision-making models". Asia-Pacific Journal of Regional Science. 6 (3): 961–991. Bibcode:2022AJPRS...6..961D. doi:10.1007/s41685-022-00248-5. ISSN 2509-7954. PMC 9294842.

- ^ a b c González-Ruibal, Alfredo (2014). An Archaeology of Resistance: Materiality and Time in an African Borderland. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-3091-0.

- ^ a b c d González-Ruibal, Alfredo (2024-03-01). "Landscapes of Memory and Power: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Kingdom in Ethiopia". African Archaeological Review. 41 (1): 71–95. doi:10.1007/s10437-024-09575-8. hdl:10261/361960. ISSN 1572-9842.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Webster, James; Chretien, Jean-Pierre (1992). "The Great Lakes region: 1500–1800". General History of Africa: Volume 5. UNESCO Publishing. Archived from the original on 2024-03-03. Retrieved 2024-03-03.

- ^ Adefuye, Ade (1976). "Palwo Economy, Society and Politics". Transafrican Journal of History. 5 (2). Gideon Were Productions: 1–20. JSTOR 24520233. Archived from the original on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ "Songora People and their Culture in Uganda". Archived from the original on 31 May 2023. Retrieved 18 Feb 2024.

- ^ a b Katoke, Israel (1970). The Making of the Karagwe Kingdom (PDF). East African Publishing House. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-05-21. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Betbeder, Paul (1971). "The Kingdom of Buzinza". Journal of World History. 13 (1). University of Hawaii Press. Archived from the original on 2024-03-08. Retrieved 2024-03-07.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Kent, Raymond (1992). "Madagascar and the islands of the Indian Ocean". General History of Africa: Volume 5. UNESCO Publishing. Archived from the original on 2024-03-03. Retrieved 2024-03-03.

- ^ Simmons, Adam (2023). "A Short Note on Queen Gaua: A New Last Known Ruler of Dotawo (r. around 1520–6)?". Dotawo: A Journal of Nubian Studies. doi:10.5070/D60060625.

- ^ Pirouet, Louise (1978). "Black Evangelists: the Spread of Christianity in Uganda". The Journal of African History. 20 (2). Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ a b c Uzoigwe, Godfrey; Denoon, Donald (1975). "A History of Kigezi in South-West Uganda". International Journal of African Historical Studies. 8. Boston University African Studies Center. doi:10.2307/217613. JSTOR 217613. Archived from the original on 2024-03-01. Retrieved 2024-03-01.

- ^ Gezon, Lisa L. (1999). "Of Shrimps and Spirit Possession:Toward a Political Ecology of Resource Management in Northern Madagascar". American Anthropologist. 101 (1): 58–67. doi:10.1525/aa.1999.101.1.58. ISSN 1548-1433.

- ^ Gilli, Eric (2019), Gilli, Eric (ed.), "The People of the Ankarana", The Ankarana Plateau in Madagascar: Tsingy, Caves, Volcanoes and Sapphires, Cave and Karst Systems of the World, Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 131–135, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-99879-4_10, ISBN 978-3-319-99879-4, retrieved 2024-12-15

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Allen, Phillip (1995). Madagascar: Conflicts Of Authority In The Great Island. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429036057. ISBN 978-0-429-03605-7.

- ^ Huggins, Chris; Mastaki, Christol (2019). "The political economy of land law and policy reform in the Democratic Republic of Congo: an institutional bricolage approach". The Canadian Journal of Development Studies. 41 (2). University of Toronto Press: 260–278. doi:10.1080/02255189.2019.1683519. S2CID 211315785. Archived from the original on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Katoke, Israel (1970). "The country". The Making of the Karagwe Kingdom (PDF). East African Publishing House. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2023-05-21. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Fosbrooke, H. (1934). "Some Aspects of the Kimwani Fishing Culture, with Comparative Notes on Alien Methods". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 64: 1–22. doi:10.2307/2843944. JSTOR 2843944. Archived from the original on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Medard, Henri; Doyle, Shane (2007). Slavery in the Great Lakes Region of East Africa. Longhouse Publishing Services. ISBN 978-0-8214-4574-7. Archived from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 8 March 2024.

- ^ Evers, Sandra (2002). Constructing History, Culture and Inequality: The Betsileo in the Extreme Southern Highlands of Madagascar. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-12460-8.

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (2016), "Malagasy empires (Sakalava and Merina)", The Encyclopedia of Empire, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 1–6, doi:10.1002/9781118455074.wbeoe056, ISBN 978-1-118-45507-4, retrieved 2024-12-17

- ^ "Fipa | Bantu-speaking, Tanzania, Zambia | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-01-07.

- ^ a b Smythe, Kathleen R. (2006). Fipa Families: Reproduction and Catholic Evangelization in Nkansi, Ufipa, 1880–1960. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 978-0-313-09437-8.

- ^ Weiss, Brad (1996). The Making and Unmaking of the Haya Lived World. Duke University Press. ISBN 0-8223-1722-2. Archived from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-18.

- ^ Umair Mirza (2005). Encyclopedia of African History And Culture, Volume 3.

- ^ Alstack, Cornery N.; MA (History) (2023-01-01). "History of Buha Pre-Colonial Social Formation up to 1890". History of Buha Pre-Colonial Social Formation up to 1890.

- ^ McMaster, Mary (2005). "Language Shift and its Reflection in African Archaeology: Cord rouletting in the Uele and Interlacustrine regions". Journal of the British Institute in Eastern Africa. 40 (1): 49. doi:10.1080/00672700509480413. S2CID 162229329. Archived from the original on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-05.

- ^ Pearson, Mike Parker (2018-07-01). "Collective and single burial in Madagascar". HAL (Le Centre Pour la Communication Scientifique Directe).

- ^ Parker Pearson, Mike (1999). "Class and rubbish". Historical Archaeology. Routledge. pp. 171–183. doi:10.4324/9780203208816-18. ISBN 978-0-203-20881-6.

- ^ Rajaonah, Faranirina V. (2020-06-30), "Women in Madagascar", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of African History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277734.013.532, ISBN 978-0-19-027773-4, retrieved 2024-12-15

- ^ Campbell, Gwyn (1981). "Madagascar and the Slave Trade, 1810–1895". The Journal of African History. 22 (2): 203–227. doi:10.1017/S0021853700019411. ISSN 1469-5138.

- ^ de Barros, Philip (2012). "The Bassar Chiefdom in the context of theories of political economy". Power and Landscape in Atlantic West Africa (PDF). Cambridge University Press. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-12-10. Retrieved 2024-03-15.

- ^ Ingham, Kenneth (1974). The Kingdom of Toro in Uganda. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-003-80149-8. Archived from the original on 2024-03-12. Retrieved 2024-03-12.

- ^ a b Jalata, Asafa (2010-01-01). "Oromo Peoplehood: Historical and Cultural Overview". ... And Other Works.

- ^ Winans, Edgar V. (1994). "The Head of the King: Museums and the Path to Resistance". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 36 (2): 221–241. doi:10.1017/S0010417500019034. ISSN 1475-2999.

- ^ Miller, J. M.; Werner, J. J.; Biittner, K. M.; Willoughby, P. R. (2020-06-01). "Fourteen Years of Archaeological and Heritage Research in the Iringa Region, Tanzania". African Archaeological Review. 37 (2): 271–292. doi:10.1007/s10437-020-09383-w. ISSN 1572-9842. PMC 7359695. PMID 32684659.

- ^ Reid, Richard (1998). "Mutesa and Mirambo: Thoughts on East African Warfare and Diplomacy in the Nineteenth Century". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 31 (1): 73–89. doi:10.2307/220885. ISSN 0361-7882. JSTOR 220885.

- ^ Yasin, Mohammed (2008). "Political History of the Afar in Ethiopia and Eritrea". Africa Spectrum. 43 (1). Sage Publications: 44. JSTOR 40175221. Archived from the original on 2023-07-18. Retrieved 2024-03-08.

- ^ "Geothermal for Peace: Exploration and development of the large Bidu-Dubbi geothermal prospect along the border of Ethiopia (Bidu Woreda, Afar Regional State) and Eritrea (Southern Denkhalya subregion, Southern Red Sea Region)". Archived from the original on 2024-03-13. Retrieved 2024-03-08.

- ^ Posnansky, Merrick. "The societies of Africa south of the Sahara in the Early Iron Age". General History of Africa: Volume 2. UNESCO Publishing. p. 729. Archived from the original on 2023-04-06. Retrieved 2024-02-21.

- ^ Cissoko, Sékéné Mody (1984). "The Songhay from the 12th to the 16th century". General History of Africa: Volume 4 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. pp. 196–202. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1989). Histoire des Mandingues de l'Ouest: le royaume du Gabou. KARTHALA Editions. pp. 221 Pages. ISBN 9782865372362.

- ^ a b Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1984). "Mali and the second Mandigo expansion". General History of Africa: Volume 4 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ a b Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1984). "Introduction". General History of Africa: Volume 4 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Stewart, John (2024). African States and Rulers (3rd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1707-7.

- ^ a b Adamu, Mahdi (1984). "The Hausa and their neighbours in central Sudan". General History of Africa: Volume 4 (PDF). UNESCO Publishing. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2024-02-27. Retrieved 2024-02-27.