Alonzo Clemons (born 1958) is an American savant and sculptor from Boulder, Colorado. He suffered a severe brain injury as a child that left him with a developmental disability. He achieved fame for his ability to sculpt almost any animal in a realistic and anatomically accurate three-dimensional rendering even after glancing at a picture for only mere seconds.

Alonzo Clemons | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1958 (age 67–68) Boulder, Colorado, U.S. |

| Occupation | Artist |

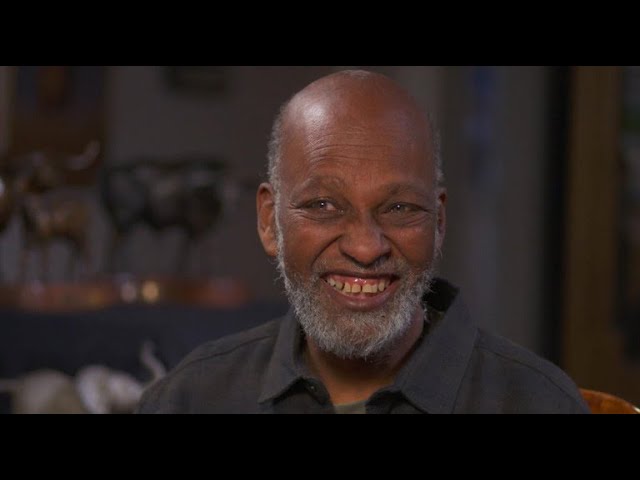

Alonzo Clemons (American English: /əˈlɑːnzoʊ ˈklɛmənz/; born 1958) is an American savant and sculptor from Boulder, Colorado. He sustained a severe brain injury as a child that left him with a developmental disability. He achieved fame for his ability to sculpt almost any animal in a realistic and anatomically accurate three-dimensional rendering even after glancing at a picture for only mere seconds.

Life

Clemons was born in Boulder, Colorado, in 1958, where he has lived his entire life.[1] At the age of three or four, Clemons experienced a severe brain injury due to a falling accident.[1][2] This left him with a developmental disability, having an IQ of around 40[2] and the mental development of a six-year-old.[1] According to his mother, molding clay was his only interest as a child ever since the accident.[3] The accident left him barely able to speak and without the ability to read, write, drive a car, or tie his shoes, meaning he would only be able to live with assistance for the rest of his life. Due to the time he grew up in, his condition was not significantly treated in his youth.[4] Nevertheless, he acquired a high level of self-sufficiency, living in his own apartment and studio next to his mother, while his improving social skills allowed him to work part-time at the local YMCA and partake in Special Olympics events in powerlifting.[2][3]

Clemons is considered an acquired savant, meaning a person that acquired a disability and in turn received a prodigious talent in a certain field, in his case sculpting.[5] Savant syndrome researcher Darold Treffert has referred to Clemons as a prodigy, stating that if he were not disabled, he would be considered a genius.[2]

Artistry

His talent for sculpting began to show shortly after his injury, when he started using clay, or, when unavailable, materials like butter, lard, or even bitumen to sculpt various animals, in most cases using only his hands.[1][2][6] As with other savants, he received and required no formal training of any sort, but is immediately able to sculpt any animal he sees, be it in person, on TV or on a photo,[7] in an accurate three-dimensional rendering, creating extremely lifelike clay sculptures that may later be cast into other materials.[8] Researchers have speculated that he is able to "freeze the frame" of what he sees at any moment in time and reproduce the exact image.[1][2] By 1987, he had already produced 500 clay pieces that filled his entire apartment.[1] One of his gallerists asserted that his ability grew the more contact to animals he had, attributing regular visits to the Denver Zoo and local animal farms to his increased skill and range.[1] While most of his works centers around animals, he has also produced sculptures of humans or religious symbols. Most of his artworks are small in size and sculpted in less than an hour,[9] however; he has also produced life-sized sculptures. His first work of the sort, Three Frolicking Foals, which was sold for $45,000 in 1987, only took him 15 days to produce, even though it required him to learn new techniques.[1] Aside from sculpting, he has also picked up pastel drawing.[2]

In 1983, he appeared in public for the first time on 60 Minutes on CBS[1] and in May of the same year had his first public exhibition at an art gallery in Denver, Colorado, where a sculpture of a bull was sold for $950.[6] For decades, he had practiced his art in obscurity, until the 1988 film Rain Man created an interest in savant syndrome.[2][4][10] Subsequently, he was shown in multiple international documentaries and TV shows, such as the German documentary Expedition ins Gehirn, leading to an increased interest in his art, which was then picked up by galleries and shown in art museums and at exhibitions around the world.

Clemons cannot describe how he sculpts and why his ability mostly relates to animals, but considers his ability to be a "gift from God" and not something he can, but rather something he has to do, an inner urge that enables him to show how he sees the world.[1][2] When asked how he does it, Alonzo will simply smile and point to his head.[6][11] His assistant has referred to working with clay as an "integral part of his personhood",[2] while he himself stated that he would be miserable if he were unable to sculpt.[5]

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Garcia, Joseph (January 12, 1987). "Retarded Sculptor Continues to Astound Public, Doctors". Associated Press. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Allen, Jaclyn (September 25, 2017). "Boulder savant creates inspiring sculptures with national following". Denver7. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Treffert, Darold. "Alonzo Clemons — Genius Among Us". Wisconsin Medical Society. Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-07.

- ^ a b Thomas, Rylee (March 4, 2020). "Alonzo Clemons: The Genius Sculptor". Out Front Magazine. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b Weisfogel, Amiel (March 19, 2018). "Meet an acquired savant". CBS. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ a b c Schmidt, William E. (July 23, 1983). "Gifted Retardates: The Search for Clues to Mysterious Talent". The New York Times. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Barry, Ann Marie Seward (1997). Visual Intelligence: Perception, Image, and Manipulation in Visual Communication. State University of New York Press. p. 85. ISBN 0-7914-3436-2.

- ^ Olson, Steve (2004). Count Down: Six Kids Vie for Glory at the World's Toughest Math Competition. Back Bay: Houghton Mifflin. p. 111. ISBN 0-618-25141-3.

- ^ McGaugh, James L. (2003). Memory and Emotion: The Making of Lasting Memories. New York City: Columbia University Press. p. 133. ISBN 0-231-12022-2.

- ^ Vorwerk-Gundermann, Liane (September 9, 2015). "Genial und doch geistig behindert". Focus (in German). Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ Wallechinsky, David; Wallace, Amy (2005). The New Book of Lists: The Original Compendium of Curious Information. Edinburgh: Canongate Books. p. 594. ISBN 1-84195-719-4.