Carter Godwin Woodson was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History. He was one of the first scholars to study the history of the African diaspora, including African-American history. A founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been called the “father of black history”.

Carter G. Woodson | |

|---|---|

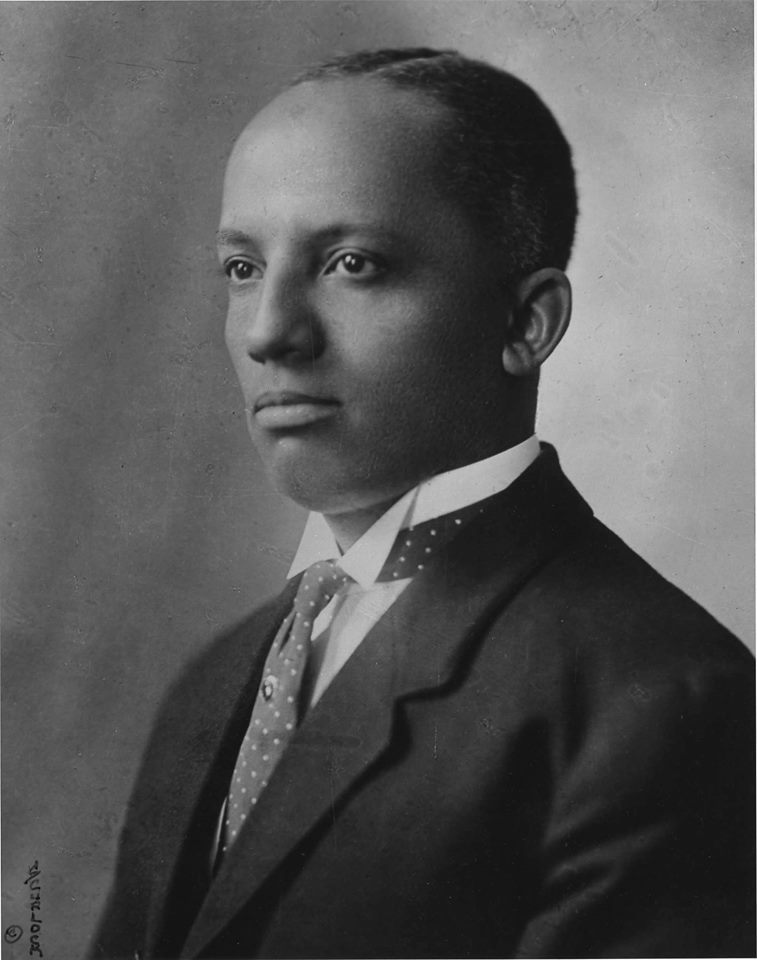

Woodson in 1915 | |

| Born | Carter Godwin Woodson December 19, 1875 New Canton, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | April 3, 1950 (aged 74) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Education | Berea College (BLitt) University of Chicago (AB, AM) Harvard University (PhD) |

| Occupations | Historian, author, journalist |

| Known for |

|

| Relatives | Bessie Woodson Yancey (sister) |

Carter Godwin Woodson (December 19, 1875 – April 3, 1950)[1] was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). He was one of the first scholars to study the history of the Black African diaspora in the United States. A founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been called the "father of Black history."[2] In February 1926, he launched the celebration of "Negro History Week," the precursor of Black History Month.[3] Woodson was an important figure to the movement of Afrocentrism,[4] due to his perspective of placing people of Sub-Saharan African descent at the center of the study of history and the human experience.[5]

Born in Virginia, the son of former slaves, Woodson had to put off schooling while he worked in the coal mines of West Virginia. He graduated from Berea College, and became a teacher and school administrator. Earning graduate degrees at the University of Chicago, Woodson then became the second African American, after W. E. B. Du Bois, to obtain a PhD degree from Harvard University. Woodson is the only person whose parents were enslaved in the United States to obtain a PhD in history.[6] Largely excluded from the uniformly-white academic history profession, Woodson realized the need to make the structures which support scholarship in black history, and black historians. He taught at Howard University and West Virginia State University, both historically black colleges, but spent most of his career in Washington, D.C., managing the ASALH, public speaking, writing, and publishing.

Early life and education

Carter G. Woodson was born in New Canton, Virginia,[7] on December 19, 1875, the son of former slaves Anne Eliza (Riddle) and James Henry Woodson.[8] Although his father was illiterate, Carter's mother, Anna, had been taught to read by her mistress. His father, James, during the Civil War, had helped Union soldiers near Richmond, after escaping from his owner, by leading them to Confederate supply stations and warehouses to raid army supplies. Thereafter, and until the war ended, James had scouted for the Union Army.[9] In 1867, Anna and James married, and later moved to West Virginia after buying a small farm. The Woodson family was extremely poor, but proud. Both Woodson's parents told him that it was the happiest day of their lives when they became free.[10] His sister was the poet, teacher, and activist Bessie Woodson Yancey.[11] Woodson was often unable to attend primary school regularly so as to help out on the farm. Through a mixture of self-instruction and four months of instruction from his two uncles, brothers of his mother who were also taught to read, Woodson was able to master most school subjects.[9][12]

At the age of seventeen, Woodson followed his older brother Robert Henry to Huntington, West Virginia, where he hoped to attend Douglass High School, a secondary school for African Americans founded there.[12] Woodson worked in the coal mines near the New River in southern West Virginia,[13] which left little time for pursuing an education.[10] At the age of twenty in 1895, Woodson was finally able to enter Douglass High School full-time and received his diploma in 1897.[12][14] From his graduation in 1897 until 1900, Woodson was employed as a teacher at a school in Winona, West Virginia. His career advanced further in 1900 when he became the principal of Douglass High School, the place where he had started his academic career. Between 1901 and 1903, Woodson took classes at Berea College in Kentucky, eventually earning his bachelor's degree in literature in 1903. From 1903 to 1907, Woodson served as a school supervisor in the Philippines, which had recently become an American territory.

Woodson later attended the University of Chicago, where he was awarded an A.B. and A.M. in 1908. He was a member of the first Black professional fraternity Sigma Pi Phi[15] and a member of Omega Psi Phi. Woodson's M.A thesis was titled "The German Policy of France in the War of Austrian Succession."[16] He completed his PhD in history at Harvard University in 1912, where he was the second African American (after W. E. B. Du Bois) to earn a doctorate.[17] His doctoral dissertation, The Disruption of Virginia, was based on research he did at the Library of Congress while teaching high school in Washington, D.C. During his research, Woodson came into conflict with his supervisors, causing professor of history, Frederick Jackson Turner, to intervene on Woodson's behalf.[16] Woodson's dissertation advisor was Albert Bushnell Hart, who had also been the advisor for Du Bois, with Edward Channing and Charles Haskins also on the committee.[18]

After earning his doctoral degree, he continued teaching, though racism from the mainstream elite institutions of the time meant he taught at other places. An early senior position was as principal of the all-Black Armstrong Manual Training School in Washington D.C.[19] He later joined the faculty at Howard University as a professor, and served there as Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences.[18]

Woodson felt that the American Historical Association (AHA) had no interest in Black history, noting that although he was a dues-paying member of the AHA, he was not allowed to attend AHA conferences.[20] Woodson became convinced he had no future in the white-dominated historical profession, and to work as a Black historian would require creating an institutional structure that would make it possible for Black scholars to study history.[20] Because Woodson lacked the funds to finance such a new institutional structure himself, he turned to philanthropist institutions such as the Carnegie Foundation, the Julius Rosenwald Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation.[20]

Career

Convinced that the role of his own people in American history and in the history of other cultures was being ignored or misrepresented among scholars, Woodson realized the need for research into the neglected past of African Americans. Along with William D. Hartgrove, George Cleveland Hall, Alexander L. Jackson, and James E. Stamps, he founded the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASLNH) on September 9, 1915, in Chicago.[21] Woodson's purpose was "to treat the records scientifically and to publish the findings of the world" in order to avoid "the awful fate of becoming a negligible factor in the thought of the world."[22] His stays at the Wabash Avenue YMCA in Chicago and in the surrounding Bronzeville neighborhood, including 1915's Lincoln Jubilee, inspired him to create the ASLNH (now the Association for the Study of African American Life and History).[23] Another inspiration was John Wesley Cromwell's 1914 book, The Negro in American History: Men and Women Eminent in the Evolution of the American of African Descent.[24]

Woodson believed that education and increasing social and professional contacts among Black and white people could reduce racism, and he promoted the organized study of African-American history partly for that purpose. He would later promote the first Negro History Week in Washington, D.C., in 1926, forerunner of Black History Month. The Association ran conferences, published The Journal of Negro History, and "particularly targeted those responsible for the education of black children."[25]

In January 1916, Woodson began publication of the scholarly Journal of Negro History. It has never missed an issue, despite the Great Depression, loss of support from foundations, and two World Wars. In 2002, it was renamed the Journal of African American History and continues to be published by the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). Woodson published The Education of the Negro Prior to 1861. His other books followed: A Century of Negro Migration (1918) and The History of the Negro Church (1927). His work The Negro in Our History has been reprinted in numerous editions and was revised by Charles H. Wesley after Woodson's death in 1950. Woodson described the purpose of the ASNLH as the "scientific study" of the "neglected aspects of Negro life and history" by training a new generation of Black people in historical research and methodology.[26] Believing that history belonged to everybody, not just the historians, Woodson sought to engage Black civic leaders, high school teachers, clergymen, women's groups and fraternal associations in his project to improve the understanding of African-American history.[26]

He served as Academic Dean of the West Virginia Collegiate Institute, now West Virginia State University, from 1920 to 1922.[27] By 1922, Woodson's experience of academic politics and intrigue had left him so disenchanted with university life that he vowed never to work in academia again.[20] He continued to write publish and lecture nationwide. He studied many aspects of African-American history. For instance, in 1924, he published the first study of free Black slave owners of 1830, in the United States.[28]

NAACP

Woodson became affiliated with the Washington, D.C., branch of the NAACP and its chairman Archibald Grimké. On January 28, 1915, Woodson wrote a letter to Grimké expressing his dissatisfaction with activities and making two proposals:

- That the branch secure an office for a center to which persons may report whatever concerns the Black race may have, and from which the Association may extend its operations into every part of the city; and

- That a canvasser be appointed to enlist members and obtain subscriptions for The Crisis, the NAACP magazine edited by W. E. B. Du Bois.

Du Bois added the proposal to divert "patronage from business establishments which do not treat races alike;" that is, boycott racially discriminatory businesses. Woodson wrote that he would cooperate as one of the twenty-five effective canvassers, adding that he would pay the office rent for one month. Grimké did not welcome Woodson's ideas.[citation needed]

Responding to Grimké's comments about his proposals, on March 18, 1915, Woodson wrote:

I am not afraid of being sued by white businessmen. In fact, I should welcome such a law suit. It would do the cause much good. Let us banish fear. We have been in this mental state for three centuries. I am a radical. I am ready to act, if I can find brave men to help me.[29]

His difference of opinion with Grimké, who wanted a more conservative course, contributed to Woodson's ending his affiliation with the NAACP.[citation needed]

Black History Month

Woodson devoted the rest of his life to historical research. He worked to preserve the history of African Americans and accumulated a collection of thousands of artifacts and publications. He noted that African-American contributions "were overlooked, ignored, and even suppressed by the writers of history textbooks and the teachers who use them."[30] Race prejudice, he concluded, "is merely the logical result of tradition, the inevitable outcome of thorough instruction to the effect that the Negro has never contributed anything to the progress of mankind."[30]

The summer of 1919 was the "Red Summer," a time of intense racial violence that saw about 1,000 people killed between May and September. Most of them were Black. In the face of widespread disillusionment felt in Black America caused by the "Red Summer", Carter worked hard to improve the understanding of Black history, later writing: "I have made every sacrifice for this movement. I have spent all my time doing this one thing and trying to do it efficiently."[31] The 1920s were a time of rising Black self-consciousness expressed variously in movements such as the Harlem Renaissance and the Universal Negro Improvement Association led by an extremely charismatic Jamaican immigrant Marcus Garvey.[31] In this atmosphere, Woodson was considered by other Black Americans to be one of their most important community leaders who discovered their "lost history."[31] Woodson's project for the "New Negro History" had a dual purpose of giving Black Americans a history to be proud of and to ensure that the overlooked role of Black people in American history was acknowledged by white historians.[31] Woodson wanted a history that would ensure that "the world see the Negro as a participant rather than as a lay figure in history."[31]

He wrote: "[W]hile the Association welcomes the cooperation of white scholars in certain projects...it proceeds also on the basis that its important objectives can be attained through Negro investigators who are in a position to develop certain aspects of the life and history of the race which cannot otherwise be treated. In the final analysis, this work must be done by Negroes.... The point here is rather that Negroes have the advantage of being able to think black."[32] Woodson's claim that only Black historians could really understand Black history anticipated the fierce debates that rocked the American historical profession in the 1960s–1970s when a younger generation of Black historians asserted that only Black people were qualified to write about Black history.[33] Despite these claims, the need for funding ensured that Woodson had several white philanthropists such as Julius Rosenwald, George Foster Peabody, and James H. Dillard elected to the board of the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.[33] Woodson preferred white patrons such as Rosenwald who were willing to finance his Association without being involved in its work.[33] Some of the white board members that Woodson recruited such as historian Albert Bushnell Hart and teacher Thomas Jesse Jones were not content to play the passive role that Woodson wanted, leading to clashes as both Hart and Jones wanted to write about Black history.[33] In 1920, both Jones and Hart resigned from the Board in protest against Woodson.[34]

In 1926, Woodson pioneered the celebration of "Negro History Week,"[35] designated for the second week in February, to coincide with marking the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass.[36] Woodson wrote of the purpose of Negro History Week as:

It is not so much a Negro History Week as it is a History Week. We should emphasise not Negro History, but the Negro in History. What we need is not a history of selected races or nations, but the history of the world void of national bias, race hatred and religious prejudice.[37]

The idea of a Negro History Week was a popular one, and to honor Negro History Week parades, breakfasts, speeches, lectures, poetry readings, banquets, and exhibits were commonly held.[37] The Black United Students and Black educators at Kent State University expanded this idea to include an entire month beginning on February 1, 1970.[38] Since 1976, every US president has designated February as Black History Month.

Colleagues

Woodson believed in self-reliance and racial respect, values he shared with Marcus Garvey, a Jamaican activist who worked in New York. Woodson became a regular columnist for Garvey's weekly Negro World.[22] Garvey believed Afro-Americans should embrace segregation, as he contended that race relations were and always would be antagonistic, and his ultimate objective was a "Back-to-Africa" plan as he believed all Afro-Americans should move to Africa. Woodson broke with Garvey when he learned that Garvey was meeting with the leaders of the Ku Klux Klan to discuss how the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the Klan could work together to achieve his "Back-to-Africa" plans.[22]

Woodson's political activism placed him at the center of a circle of many Black intellectuals and activists from the 1920s to the 1940s. He corresponded with W. E. B. Du Bois, John E. Bruce, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg, Hubert H. Harrison, and T. Thomas Fortune, among others. Even with the extended duties of the Association, Woodson was able to write academic works such as The History of the Negro Church (1922), The Mis-Education of the Negro (1933), and others which continue to have wide readership.

Woodson did not shy away from controversial subjects, and used the pages of Black World to contribute to debates. One issue related to West Indian/African-American relations. He summarized that "the West Indian Negro is free," and observed that West Indian societies had been more successful at properly dedicating the necessary amounts of time and resources needed to educate and emancipate people genuinely. Woodson approved of efforts by West Indians to include materials related to Black history and culture into their school curricula. [citation needed]

Woodson was ostracized by some of his contemporaries because of his insistence on defining a category of history related to ethnic culture and race. At the time, these educators felt that it was wrong to teach or understand African-American history as separate from more general American history. According to these educators, "Negroes" were simply Americans, darker skinned, but with no history apart from that of any other. Thus Woodson's efforts to get Black culture and history into the curricula of institutions, even historically Black colleges, were often unsuccessful. [citation needed]

Criticism of Christian churches

Woodson criticized Christian churches for offering limited opportunity and requiring segregation. In 1933, he wrote in The Mis-Education of the Negro that “the ritualistic churches into which these Negroes have gone do not touch the masses, and they show no promising future for racial development. Such institutions are controlled by those who offer the Negroes only limited opportunity and then sometimes on the condition that they be segregated in the court of the gentiles outside of the temple of Jehovah."[39]

Death and legacy

Woodson died suddenly from a heart attack in the office within his home in the Shaw, Washington, D.C., neighborhood on April 3, 1950, at the age of 74. He is buried at Lincoln Memorial Cemetery in Suitland, Maryland.

The time that schools have set aside each year to focus on African-American history is Woodson's most visible legacy. His determination to further the recognition of the Black race in American and world history, however, inspired countless other scholars. Woodson remained focused on his work throughout his life. Many see him as a man of vision and understanding. Although Woodson was among the ranks of the educated few, he did not feel particularly sentimental about elite educational institutions.[citation needed] The Association and journal that he started are still operating, and both have earned intellectual respect.

Woodson's other far-reaching activities included the founding in 1920 of The Associated Publishers in Washington, D.C. This enabled the publication of books concerning Black people that might not have been supported in the rest of the market. He founded Negro History Week in 1926 (now known as Black History Month). He created the Negro History Bulletin, developed for teachers in elementary and high school grades, and published continuously since 1937. Woodson also influenced the Association's direction and subsidizing of research in African-American history. He wrote numerous articles, monographs, and books on Black people. The Negro in Our History reached its 11th edition in 1966, when it had sold more than 90,000 copies.

Dorothy Porter Wesley recalled: "Woodson would wrap up his publications, take them to the post office and have dinner at the YMCA. He would teasingly decline her dinner invitations saying, 'No, you are trying to marry me off. I am married to my work.'"[40] Woodson's most cherished ambition, a six-volume Encyclopedia Africana, was incomplete at the time of his death.

In 1998, musician and ethnomusicologist Craig Woodson (once of the experimental rock band The United States of America), arranged a ceremony to apologize for his white ancestors' involvement in the slavery that had oppressed members of Carter G. Woodson's family. Following the reconciliation, both sides of the family developed the Black White Families Reconciliation (BWFR) Protocol, using the creative arts, particularly drumming and storytelling, with the aim of healing racial divides within Black and white families who share a surname.[41]

Honors and tributes

- In 1926, Woodson received the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Spingarn Medal.

- The Carter G. Woodson Book Award was established in 1974 "for the most distinguished social science books appropriate for young readers that depict ethnicity in the United States."[42]

- The U.S. Postal Service issued a 20-cent stamp honoring Woodson in 1984.[43]

- In 1992, the Library of Congress held an exhibition entitled Moving Back Barriers: The Legacy of Carter G. Woodson. Woodson had donated his collection of 5,000 items from the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries to the Library.

- A Carter G. Woodson Memorial statue was dedicated in 1995 in Huntington, West Virginia, near where he had gone to high school and taught.[44]

- His Washington, D.C. home has been preserved and designated the Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site.

- In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Carter G. Woodson on his list of 100 Greatest African Americans.[45]

- In 2015, a bronze statue of Woodson was placed in the park named for him in Washington, D.C.[46]

- On February 1, 2018, he was honored with a Google Doodle.[47]

Places named in honor of Woodson

California

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School in Los Angeles.

- Carter G. Woodson Public Charter School in Fresno.

Florida

- Carter G. Woodson Park, in Oakland Park.[48]

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School was located in Oakland Park. It was closed in 1965 when the Broward County Public Schools system was desegregated.

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum in St. Petersburg.

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary School in Jacksonville.

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson PK–8 Leadership Academy in Tampa, Florida.

Georgia

- Carter G. Woodson Elementary in Atlanta.

Illinois

- Carter G. Woodson Regional Library in Chicago.

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in Chicago.

- Carter G. Woodson Library of Malcolm X College in Chicago

Indiana

- Carter G. Woodson Library in Gary.

Kentucky

- Carter G. Woodson Academy in Lexington.

- Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education, Berea College, in Berea.[49]

Louisiana

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in New Orleans.

- Carter G. Woodson Liberal Arts Building at Grambling State University, built in 1915, in Grambling.

- Carter G. Woodson High School in Lawtell, Louisiana.

Maryland

Minnesota

- Woodson Institute for Student Excellence in Minneapolis.

New York

- PS 23 Carter G. Woodson School in Brooklyn. PS 23 Carter G. Woodson

- Carter G. Woodson Children's Park[50] in Brooklyn.

North Carolina

- Carter G. Woodson Charter School in Winston-Salem.

Texas

Virginia

- The Carter G. Woodson Institute for African-American and African Studies at the University of Virginia, Charlottesville.[51]

- C.G. Woodson Road in his home town of New Canton.

- Carter G. Woodson Education Complex in Buckingham County, built in 2012.

- Carter G. Woodson Avenue at Virginia State University, Ettrick

- Carter G. Woodson High School, the new name of Wilbert Tucker Woodson High School in Fairfax, Virginia, to take effect at the 2024–2025 school year[52]

- Carter G. Woodson Middle School in Hopewell, Virginia[53]

Washington, D.C.

- Carter G. Woodson Junior High School was named for him. It currently hosts Friendship Collegiate Academy Public Charter School.

- The Carter G. Woodson Memorial Park is between 9th Street, Q Street and Rhode Island Avenue, NW. The park contains a cast bronze sculpture of the historian by Raymond Kaskey.

- The Carter G. Woodson Home, a National Historic Site, is located at 1538 9th St., NW, Washington, D.C.[54]

West Virginia

- Carter G. Woodson Jr. High School (renamed McKinley Jr. High School after integration in 1954) in St. Albans, built in 1932.

- Carter G. Woodson Avenue (also known as 9th Avenue) in Huntington, West Virginia. Notably, Woodson's alma mater, Douglass High School is located between Carter G. Woodson Avenue and 10th Avenue in the 1500 block.

- The Carter G. Woodson Memorial, also in Huntington, features a statue of the educator on Hal Greer Boulevard, facing the location of the former Douglass High School.[55]

Selected works

- A century of negro migration. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1918. OCLC 79947665.

- The Education of the Negro prior to 1861. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1919. hdl:2027/mdp.39076006056191. OCLC 593592787.

- The history of the Negro church. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1921. hdl:2027/emu.010002643732. OCLC 506124215.

- The Negro in Our History. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1922. OCLC 506124204.

- Free Negro owners of slaves in the United States in 1830, together with Absentee ownership of slaves in the United States in 1830. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1924. OCLC 802300957.

- Free Negro heads of families in the United States in 1830 : together with a brief treatment of the free Negro. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1925. OCLC 176986298.

- Preview of Negro orators and their orations. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1925. OCLC 703518974.

- The mind of the Negro as reflected in letters written during the crisis, 1800–1860. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1926. hdl:2027/mdp.39015002382193. ISBN 978-0837111797. OCLC 558188512.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Negro makers of history. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1928. hdl:2027/mdp.39015002382367. OCLC 558190211.

- African myths and folk tales. Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. 2009 [1928]. ISBN 978-0486114286. OCLC 853448285.

- The Rural Negro. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1930. hdl:2027/mdp.39015002602350. OCLC 613261827.

- Greene, Lorenzo J.; Woodson, Carter G. (1930). The Negro wage earner. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. hdl:2027/mdp.39015009109573. OCLC 558574532.

- The Mis-Education of the Negro. Lanham: Dancing Unicorn Books. 2017 [1933]. ISBN 978-1515415534. OCLC 987740119.

- The Negro professional man and the community, with special emphasis on the physician and the lawyer. Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History. 1934. hdl:2027/uc1.$b60460. OCLC 612967753.

- Woodson, Carter Godwin; Wesiley, Charles H. (1959) [1935]. The story of the Negro retold (4th ed.). Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. hdl:2027/mdp.39015002382680. OCLC 558574303.

- The African background outlined : or, Handbook for the study of the Negro (DjVu). Washington, DC: Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc. 2006 [1936]. OCLC 219632552.

- African heroes and heroines. Washington, DC: Associated Publishers. 1939. hdl:2027/mdp.39015003980995. OCLC 643987347.

- Grimké, F.J. (1942). Woodson, Carter Godwin (ed.). The works of Francis J. Grimke. The Associated Publishers, Inc. OCLC 600171452.

- Woodson, Carter (2008). Scott, Daryl Michael (ed.). Carter G. Woodson's appeal. Washington, DC: ASALH Press. ISBN 978-0976811190. OCLC 922360363.

See also

References

- ^ Du Bois, William Edward Burghardt (1997). The correspondence of W. E. B. Du Bois, Volume 3. University of Massachusetts Press. p. 282. ISBN 1-55849-105-8. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Bennett, Lerone Jr. (2005). "Carter G. Woodson, Father of Black History". United States Department of State. Archived from the original on April 1, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Daryl Michael Scott, "The History of Black History Month" Archived July 23, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, on ASALH website.

- ^ Early, Gerald (May 17, 2002). "Afrocentrism". Encyclopaedia Britannica. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ Wiggan, Greg (2016). Dreaming of a Place Called Home. Springer. p. 14. ISBN 978-9463004411.

- ^ "Carter G. Woodson: Winona, WV – New River Gorge National Park and Preserve (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on June 16, 2019. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- ^ "Virginian Started Negro History Week in 1926". Norfolk (VA) New Journal and Guide, February 9, 1957, p. 11.

- ^ Betty J. Edwards, "He Made World Respect Negroes". Chicago Defender, February 8, 1965, p. 9.

- ^ a b Táíwò, Olúfẹ́mi O. (2022). Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took over Identity Politics (and Everything Else). Haymarket Books. pp. 33–35. ISBN 978-1-64259-688-5.

- ^ a b Winston, Michael R. (1975). "Carter Godwin Woodson: Prophet of a Black Tradition". The Journal of Negro History. 60 (4). University of Chicago Press: 460. doi:10.2307/2717017. ISSN 0022-2992. JSTOR 2717017. S2CID 149971786.

- ^ Katharine Capshaw Smith (2008). "Bessie Woodson Yancey, African-American Poet and Social Critic". Appalachian Heritage. 36 (3): 73–77. doi:10.1353/aph.0.0060. ISSN 1940-5081. S2CID 146641392.

- ^ a b c "Civil Rights Leaders | Carter G. Woodson". naacp.org. NAACP. Retrieved January 31, 2019.

- ^ "Carter G. Woodson". New River Gorge National Park & Preserve (U.S. National Park Service). August 4, 2023. Retrieved February 17, 2024.

- ^ Maurice F. White, "Dr. Carter G. Woodson History Week Founder". Cleveland Call and Post, February 16, 1963, p. 3C.

- ^ "1904–2004: the Boule at 100: Sigma Pi Phi Fraternity holds centennial celebration". Ebony. September 2004. Archived from the original on November 23, 2004. Retrieved January 25, 2007.

- ^ a b Hughes-Warrington 2000, p. 358.

- ^ Kelly, Raina (January 28, 2010). "The End of Black History Month? Not So Fast". Newsweek.

- ^ a b Dagbovie, Pero Gaglo (2014). Carter G. Woodson in Washington, D.C.: The Father of Black History. Charleston, SC: The History Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-1625851642. Retrieved January 30, 2020.

- ^ Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). "Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography". The History Teacher. 19 (3). JSTOR: 405–425. doi:10.2307/493381. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 493381.

- ^ a b c d Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). "Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography". The History Teacher. 19 (3). JSTOR: 406. doi:10.2307/493381. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 493381.

- ^ Scott, Daryl Michael. "The founding of the association September 9, 1915". Carter G. Woodson Center. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ a b c Hughes-Warrington 2000, p. 359.

- ^ "Young Men's Christian Association – Wabash Avenue records". The University of Chicago Library. Black Metropolis Research Consortium. Retrieved December 1, 2018.

- ^ Carrillo, Karen Juanita, African American History Day by Day: A Reference Guide to Events. ABC-CLIO, August 22, 2012, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Corbould, Claire, Becoming African Americans: The Public Life of Harlem 1919–1939, Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press, 2009, p. 88.

- ^ a b Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). "Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography". The History Teacher. 19 (3). JSTOR: 407. doi:10.2307/493381. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 493381.

- ^ Osborne, Kellie (January 29, 2015). "West Virginia State University Celebrates Black History Month with Series of Events". West Virginia State University. Retrieved February 5, 2015.

- ^ Wesley, Charles H., "Carter G. Woodson as a Scholar", The Journal of Negro History, Vol. 36, No. 1 (January 1951), pp. 12–24, in JSTOR.

- ^ Cobb, Jr., Charles E. (2008). On the Road to Freedom: A Guided Tour of the Civil Rights Trail. Algonquin Books. p. 28. ISBN 978-1565124394.

- ^ a b Current Biography 1944, p. 742.

- ^ a b c d e Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). "Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography". The History Teacher. 19 (3). JSTOR: 408. doi:10.2307/493381. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 493381.

- ^ Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). "Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography". The History Teacher. 19 (3). JSTOR: 408–409. doi:10.2307/493381. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 493381.

- ^ a b c d Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). "Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography". The History Teacher. 19 (3). JSTOR: 409. doi:10.2307/493381. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 493381.

- ^ Hine, Darlene Clark (1986). "Carter G. Woodson, White Philanthropy and Negro Historiography". The History Teacher. 19 (3). JSTOR: 413. doi:10.2307/493381. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 493381.

- ^ Corbould (2009), p. 106.

- ^ Beasley, Delilah L. (February 14, 1926). "Activities Among Negroes". Oakland Tribune. p. X–5. Retrieved February 7, 2022 – via NewspaperArchive.

- ^ a b Hughes-Warrington 2000, p. 360.

- ^ Wilson, Milton. "Involvement/2 Years Later: A Report On Programming In The Area Of Black Student Concerns At Kent State University, 1968–1970". Special Collections and Archives: Milton E. Wilson, Jr. papers, 1965–1994. Kent State University. Retrieved September 28, 2012.

- ^ Woodson, Carter Godwin (1990) [1933]. The Mis-education of the Negro. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press. p. 55. ISBN 0-86543-170-1. OCLC 21176196 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Trescott, Jacqueline (February 10, 1992). "Black History's Early Champion". The Washington Post.

- ^ "Black-White Woodson Reconciliation", Drums of Humanity, October 2, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2021.

- ^ "About the Carter G. Woodson Book Award". National Council for the Social Studies. December 5, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2015.

- ^ "Stamp Series". United States Postal Service. Archived from the original on August 10, 2013. Retrieved September 2, 2013.

- ^ Pierson, Lacie (February 6, 2016). "Huntington pays tribute to Carter G. Woodson". The Herald-Dispatch. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ Asante, Molefi Kete (2002). 100 Greatest African Americans: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Amherst, New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 1573929638.

- ^ "Carter G Woodson Memorial Park Project". DC.gov. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- ^ "Celebrating Carter G. Woodson". Google Doodles. February 1, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Dr. Carter G. Wilson Festival". The City of Oakland Park. Archived from the original on February 6, 2009. Retrieved December 15, 2008.

- ^ "Carter G. Woodson Center for Interracial Education". Berea College. Retrieved September 9, 2023.

- ^ "Carter G. Woodson Children's Park : NYC Parks".

- ^ "Carter G Woodson Institute". University of Virginia. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ "Woodson High School Renaming". Fairfax County Public Schools. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ "Carter G Woodson Homepage Hopewell city Public Schools".

- ^ "Directions – Carter G. Woodson Home National Historic Site". National Park Service. January 31, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ "Carter G. Woodson Memorial". Almost Heaven – West Virginia.

Bibliography

- "Carter G. Woodson." Notable Black American Men, Book II, edited by Jessie Carney Smith (Gale, 1998) online

- Alridge, Derrick P. "Woodson, Carter G." in Simon J. Bronner (ed.), Encyclopedia of American Studies (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015), online.

- Dagbovie, Pero Gaglo. The Early Black History Movement, Carter G. Woodson, and Lorenzo Johnston Greene (University of Illinois Press, 2007).

- Goggin, Jacqueline. "Countering White Racist Scholarship: Carter G. Woodson and the Journal of Negro History". Journal of Negro History 68.4 (1983): 355–375 online.

- Goggin, Jacqueline Anne. Carter G. Woodson: A Life in Black History (LSU Press, 1997).

- Hughes-Warrington, Marnie (2000). Fifty Key Thinkers on History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415169828.

- Meier, August, and Elliott Rudwick. Black History and the Historical Profession, 1915–1980 (University of Illinois Press, 1986).

- Romero, Patricia W. "Carter G. Woodson: a biography" (PhD. Diss. The Ohio State University, 1971) online.

- Roche, A. "Carter G. Woodson and the Development of Transformative Scholarship", in James Banks (ed.), Multicultural Education, Transformative Knowledge, and Action: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (Teachers College Press, 1996).

- Winston, Michael R. "Carter Godwin Woodson: Prophet of a Black tradition". Journal of Negro History 60.4 (1975): 459–463. online

Primary sources

- Miller, M. Sammy, and Carter G. Woodson. "The Sixtieth Anniversary of The Journal of Negro History 1916–1976: Letters from Dr. Carter G. Woodson to Mrs. Mary Church Terrell". Journal of Negro History 61.1 (1976): 1–6 online.

External links

- The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH)

- Audiobook version of "The Mis-Education of the Negro"

- Homepage for Carter G. Woodson's Appeal

- Daryl Michael Scott, "The History of Black History Month", ASALH website

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American History Museum

- "Some St. Albans Schools over the years" Archived January 12, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, St. Albans Historical Society.

- Dr. Carter G. Woodson African American Museum

- Dr Carter Godwin Woodson at Find a Grave

- Part of his life is retold in the 1950 radio drama "Recorder of History – Dr. Carter G. Woodson", a presentation from Destination Freedom, written by Richard Durham

Woodson's writings

- Works by Carter G. Woodson at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Carter G. Woodson at the Internet Archive

- Works by Carter G. Woodson at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Woodson, Carter Godwin (1992). The History of the Negro Church. Associated Publishers. ISBN 0874980003.

- Woodson, Carter Godwin (2005). Mis-Education of the Negro. ASALH Press. ISBN 0976811103.

Archival Collections

- Carter Godwin Woodson Correspondence with Charles H. Wesley held by Princeton University Library Special Collections

- Carter Godwin Woodson collection, 1876–1999 held by Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University

- Carter Godwin Woodson papers, 1736–1974 held by Library of Congress Manuscript Division

Other information about Woodson

- "Dr. Carter Godwin Woodson & the Observance of African History"

- "Library of Congress Initiates Traveling Exhibits Program", The Library of Congress, June 18, 1993.

- "Library of Congress Traveling Exhibit Examines Contributions of Black History Pioneer C.G. Woodson", The Library of Congress, October 7, 1993

- Carter G. Woodson Wax Figure at the National Great Blacks in Wax Museum