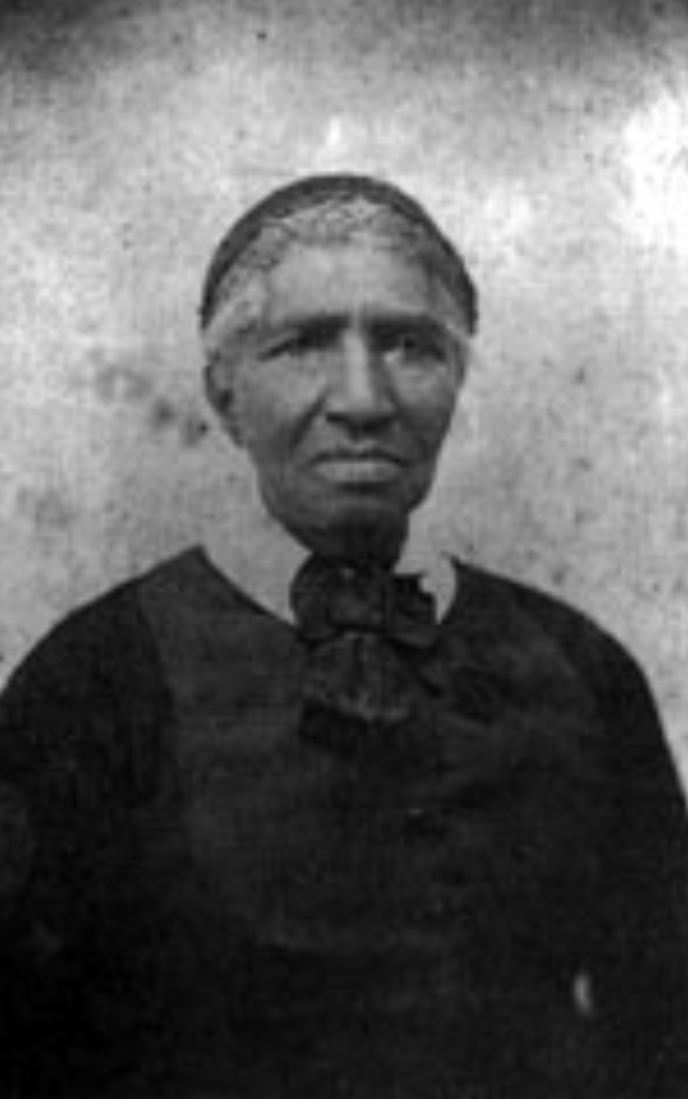

Clara Brown (c. 1800–1885) was a former enslaved woman from Virginia and Kentucky who became a community leader, philanthropist and aided settlement of former slaves during the time of Colorado’s Gold Rush. She was known as the ‘Angel of the Rockies’ and made her mark as Colorado’s first black settler and a prosperous entrepreneur.

Clara Brown | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | January 1, 1800 Near Fredericksburg, Virginia, United States |

| Died | October 23, 1885 (aged 85) Denver, Colorado, United States |

| Other names | Aunt Clara Brown |

| Occupations | Cook, laundress, midwife, nursemaid, and real estate investor |

| Known for | Being the first Black settler in Colorado, philanthropist, and abolitionist |

Clara Brown (January 1, 1800 – October 23, 1885) was a former enslaved woman from Virginia and Kentucky who became a community leader and philanthropist. She helped formerly enslaved people become settled during Colorado's Gold Rush. She was known as the "Angel of the Rockies" and made her mark as "Colorado's first black settler and a prosperous entrepreneur".[1]

Brown, born in Virginia in 1800,[a] moved to Logan County, Kentucky, with her family. She married another enslaved person when she was 18 and they had four children. In 1835, Brown's family was broken apart when they were all sold to different slave owners. When Brown was 56, she received her freedom but was required by law to leave the state. She worked her way to Denver, Colorado, as a cook and laundress on a wagon train, thus functioning as a frontierswoman.

Brown settled in the mining town now called Central City, Colorado, where she worked as a laundress, cook, and midwife. With the money she made, she invested in properties and mines in nearby towns. Known as "Aunt Clara" for her emotional and financial support, Brown was a founding member of a Sunday school that was held in her home.

At the end of the Civil War, Brown could freely travel and liquidated all of her investments to travel to Kentucky to find her daughter. Although she was unsuccessful, she paid the way for 16 or more relatives and others who were former slaves to move to Colorado. Finally, in 1882 she reunited with her daughter Eliza Jane and Eliza Jane's daughter.

In 1885, the last year of her life, Clara Brown was voted into the Society of Colorado Pioneers for her role in Colorado's early history. Brown was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1989 and the Colorado Business Hall of Fame in 2022.[3] The story of her life was told through the opera Gabriel's Daughter at the Central City Opera House in 2003.

Early life

Clara Brown was born into slavery near Fredericksburg, Virginia, on January 1, 1800.[2][a] At a young age, Clara and her mother were sold to Ambrose Smith, a tobacco farmer in Virginia, and worked in the fields.[4] Clara married a slave named Richard at 18 years of age. Together they had four children: Richard, Margaret, Paulina Ann, and Eliza Jane. Paulina and Eliza were twins. Paulina drowned when she was 8.[2] She was also held at some point by the Smith family in Kentucky.[4]

In 1835, Brown's owner, Ambrose Smith, died. To settle the estate, Brown's family were sold separately at a slave auction, after which they were sent to different, distant locations. A plantation owner from Kentucky, George Brown, sensed her intelligence and strength and placed high bids to attain her.[2]

Freedom

At the age of 56, Clara Brown was granted her freedom,[2] as stipulated in George Brown's will. She left the state upon receiving her freedom according to a Kentucky law.[5]

Kentucky to Colorado

Brown was hired as a maid and cook by a family heading to the westward departure point of Leavenworth in Kansas Territory.[2] From there, Brown was hired by Colonel Benjamin Wadsworth in April 1859 to work on a wagon train as a cook for 26 men. It was a hot, difficult eight-week journey to Denver, made more uncomfortable by the complaints of a southern man about a black woman traveling with them.[6] Brown is believed to be Colorado’s gold rush first African American woman.[4]

Denver and Central City

In the Denver area, Brown settled in nearby Auraria where she worked at the City Bakery. She was one of the founding members of the nondenominational Union Sunday school through her affiliation with two Methodist missionary ministers. Following the tide of miners heading into the mountains, Brown set up the first laundry in Gilpin County in Gregory Gulch, now called Central City, Colorado. She also worked as a midwife, cook[6] and nursemaid. Brown's income grew substantially when she expanded her laundry business after taking a partner.[5] She invested her earnings in mine claims and land and within several years had accumulated $10,000 in savings[6] and reportedly owned 16 lots in Denver, 7 houses in Central City, and property and mines in Boulder, Georgetown, and Idaho Springs.[7]

Brown gave generously of herself to those in the community. She hosted the first Methodist church services at her house and helped those in need any way she could, including newly settled Euro-Americans and Native Americans.[5][8] Called "Aunt Clara," her home was "a hospital, a home, a general refuge for those who were sick or in poverty." Brown donated to the construction of the Catholic Church and the first Protestant church in the Rocky Mountains.[5][7]

Frank C. Young, who some called the Washington Irving of the Rockies[9] said of Brown:

In our little community everyone knew everyone else, whatever might be the positive differences in social position. In this connection, I might speak of Aunt Clara Brown. She was raised in old Kentucky, and with her own freedom secured after years of persistent, patient toil, when well along in life she joined the procession of gold seekers to Gregory Gulch. Through the unusual returns of a mining camp for labor such as hers, she was able to bring out from the old plantation her children and later her children’s children [relatives]; and with them, whether aided by her efforts or stimulated by her example, have, year by year, come many others of her race, worthily represented by the Poynters, the Lees, the Nelsons and other families who are as tenacious of recognition as subjects of the 'little kingdom' as you or I may be.[10]

Attempts to find her family and aid to former slaves

Letters were sent to locate her family with the aid of literate friends. Brown heard that her husband Richard and daughter Margaret had both died and her son Richard was lost, but she vowed to find her daughter Eliza Jane.[7][8] At the end of the Civil War, she liquidated her holdings to travel back to Gallatin, Kentucky. She did not find Eliza Jane, but she helped 16[5][7][8] relatives and others who were former enslaved people travel to Colorado by train and wagon train. She helped them find work once they were settled.[5][7][8] Brown also went to Kansas in 1879, to help former slaves "build a community and farm the land."[4] At eighty years of age, Brown's funds were depleted through charitable contributions, her efforts to find her family, and having been cheated by real estate agents.[5]

Brown moved to Denver when she could no longer sustain the higher altitude and lived in the home of a friend. After years of writing letters, Brown heard that her daughter lived in Council Bluffs, Iowa, and traveled there at 82 years of age to meet her. The Council Bluffs Nonpareil reported on March 4, 1882, that Brown was "still strong, vigorous, tall, her hair thickly streaked with gray, her face kind." Brown returned to Denver with her granddaughter after a lengthy visit and was later visited by her daughter, Eliza Jane, until Brown's death. In remembrance of her pioneering role in Colorado history, she was voted into the Society of Colorado Pioneers and interviewed by the Denver Tribune-Republican on June 26, 1885.[11]

Death and memorials

Clara Brown died in Denver on October 23, 1885[2] and was buried in Denver's Riverside Cemetery. Colorado state dignitaries were in attendance at her funeral, including Denver mayor John Long Routt and governor James Benton Grant.[12]

The Central City Opera House dedicated a permanent memorial chair in her name.[13][3] Brown is the subject of the opera Gabriel's Daughter by Henry Mollicone and William Luce, which premiered at Central City Opera in 2003.[14]

Brown was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1989 and on January 27, 2022, she was inducted into the Colorado Business Hall of Fame. [3]

See also

- History of slavery in Colorado

- List of African American pioneers of Colorado

- Mary Green, first black settler of Arizona, similarly arriving as a domestic servant

Notes

References

- ^ a b Shirley, Gayle C. (2002). More than Petticoats. Twodot. p. 1 (n14). ISBN 0-7627-1269-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Varnell 1999, p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Clara Brown". Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

- ^ a b c d Clara Brown Biography, A&E Network.

- ^ a b c d e f g Katz 1995, chapter 7.

- ^ a b c Varnell 1999, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d e Varnell 1999, p. 3.

- ^ a b c d Reiter 1978, p. 131.

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 360.

- ^ Hill 1915, p. 362.

- ^ Varnell 1999, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Wishart 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Varnell 1999, p. 4.

- ^ Weller, Robert (July 22, 2003). "Song in Central City". Fort Collins Coloradoan. p. 16. Retrieved 2023-05-11.

Bibliography

- Clara Brown Biography (1800-1885). Biography Channel. A&E Network. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Colorado Women's Hall of Fame, Clara Brown. Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. 2011. Retrieved 13 June 2011.

- Hill, A. (1915). Colorado pioneers in picture and story. Denver: Brock-Hafner Press.

- Katz, W (1995). "Chapter 7. Clara Brown of Colorado". Black Women of the Old West. New York: Antheum Books for Young Readers, Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781439115862. ISBN 978-0-689-31944-0.

- Reiter, Joan S. (1978). The Old West: The Women. Time-Life Books. ISBN 0-8094-1514-3

- Varnell, Jeanne (1999). Women of Consequence: The Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. Boulder: Johnson Press.ISBN 1-55566-214-5.

- Wishart, David J. (2004). Encyclopedia of the Great Plains. University of Nebraska Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-8032-4787-1.