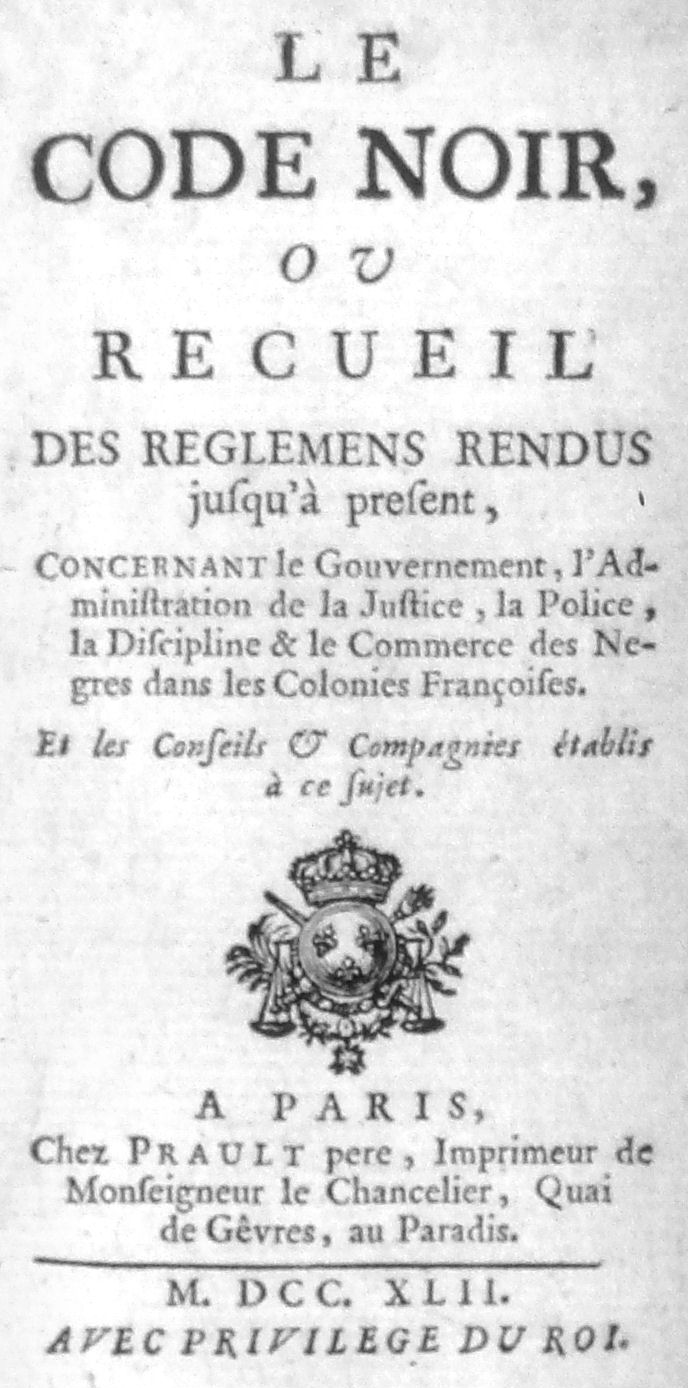

The Code Noir (French pronunciation: [kɔd nwaʁ], Black Code) was a decree passed by the French King Louis XIV in 1685 defining the conditions of slavery in the French colonial empire.

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Racial segregation |

|---|

|

The Code noir (French pronunciation: [kɔd nwaʁ], Black code) was a decree passed by King Louis XIV of France in 1685, defining the conditions of slavery in the Antilles, then also Louisiana, and served as the code for slavery conduct in the French colonies up until 1789, the year marking the beginning of the French Revolution. The decree restricted the activities of free people of color, mandated conversion to Catholicism for all enslaved people throughout the empire, defined the punishments meted out to them, and ordered the expulsion of all Jews from France's colonies. The code has been described by historian of modern France Tyler Stovall as "one of the most extensive official documents on race, slavery, and freedom ever drawn up in Europe".[1]

History

Context

At the time, there were two common law statutes in effect in Martinique: that pertaining to French nationals, which was the Custom of Paris as well as laws for foreigners, which did not include rules particular to soldiers, nobles, or clergy. These statutes were included in the Edict of May 1664 that established the French West India Company. The American Isles were enfeoffed or conceded to the company, whose formation had replaced the Company of Saint Christopher (1626–1635), but would eventually be succeeded by the Company of the American Isles (1635–1664). The Indigenous population, called Caribbean Indians (Indiens caraïbes), were seen as naturalized French subjects, and were provided the same rights as French nationals upon their baptism. It was forbidden to enslave Indigenous peoples, or to sell them as slaves. Two populations were provided for: natural populations and native French, as the Edict of 1664 did not describe slaves or the importation of a black population. The French West India Company had gone bankrupt in 1674, with its commercial activities having been transferred to the Senegal Company and its territories returned to the Crown. The rulings of the Sovereign Council of Martinique patched the legal hole concerning slave populations. In 1652, at the behest of Jesuit missionaries, the Council reified the rule that slaves, like domestic servants, shall not be made to work on Sundays and in 1664, held that slaves would be required to be baptized and to attend catechism.[2][3]

Codes governing slavery had already been established in many European colonies in the Americas, such as the 1661 Barbados Slave Code. At this time in the Caribbean, Jews were mostly active in the Dutch colonies, so their presence was seen as an unwelcome Dutch influence in French colonial life.[4] French Plantation owners largely governed their land and holdings in absentia, with subordinate workers dictating the day-to-day running of the plantations. Because of their enormous population, in addition to the harsh conditions facing slaves, small-scale slave revolts were common. Although the Code Noir contained a few, minor humanistic provisions, the Code noir was generally flaunted, in particular regarding protection for slaves and limitations on corporal punishment.[5]

The Code Noir aimed to provide a legal framework for slavery, to establish protocols governing the conditions of the slaves in the French colonies, and appears to make an attempt at ending the illegal slave trade. Strict religious morals were also imposed in the crafting of the Code noir; in part a result of the influence of the influx of Catholic leaders arriving in the Antilles between 1673 and 1685.

The Code Noir was also conceived to “maintain the discipline of the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman church”[6] in the French colonies. It required that all enslaved people of African descent in the French colonies receive baptism, religious instruction, and the same practices and sacraments for slaves as it did for free persons. While it did grant enslaved people the right to rest on Sundays and holidays, to formally marry through the church, and to be buried in proper cemeteries, forced religious conversion was just one of the many methods that France used to attempt to 'civilize' and exert their imperial control over the Black population in the French colonies.

The Code thus gave a guarantee of morality to the Catholic nobility that arrived in Martinique between 1673 and 1685.[7]

Inception

In 1681, the King decided to create a statute for the black population of the French Caribbean and delegated its writing to Colbert, who, in turn, requested memoranda from the colonial intendant of Martinique, Jean-Baptiste Patoulet and later from his replacement, Michel Bégon, as well as the governor general of the Caribbean, Charles de Courbon, comte de Blenac (1622–1696). The Mémoire (memorandum) of 30 April 1681 from the King to the intendant (who was probably Colbert), expressed the utility of making an ordinance specific to the Antilles.

The study, which incorporated local legal customs, decisions, and jurisprudence of the Sovereign Council, as well as a number of rulings by the King's Council, was challenged by the members of the Sovereign Council. When negotiations settled, the draft was sent to the chancellery, which retained what was essential and only reinforced or streamlined the articles such that they were compatible with preexisting laws and institutions.

The earliest of these constituent ordinances was drafted by the Naval Minister (secrétaire d'État à la Marine) Marquis de Seignelay and promulgated in March 1685 by King Louis XIV with the title "Ordonnance ou édit de mars 1685 sur les esclaves des îles de l'Amérique". The only known manuscript of this law to have been preserved is currently in the French National Overseas Archives (Archives nationales d'outre-mer). The Marquis de Seignelay wrote the draft using legal briefs written by the first intendant of the French islands of the Americas, Jean-Baptiste Patoulet, as well as those of his successor Michel Bégon. Legal historians have debated whether other sources, such as Roman slavery laws, were consulted in the drafting of this original text. Studies of correspondence from Patoulet suggest that the 1685 ordinance drew mostly on local regulations provided in the colonial intendant's memoranda.[5][8]

Based on the fundamental law that any man who sets foot on French soil is free, various parliaments refused to pass the original Ordonnance ou édit de mars 1685 sur les esclaves des îles de l'Amérique which was ultimately instituted only in the colonies for which the edict was written: the Sovereign Council of Martinique on 6 August 1685, Guadeloupe on 10 December of the same year, and in Petit-Goâve before the Council of the French colony of Saint-Domingue on 6 May 1687.[9] Finally, the Code was passed before the councils of Cayenne and Guiana on 5 May 1704.[9]

Subsequent evolution

There existed many editions of the Code noir. While their differences were often formal, they sometimes differed greatly from one another, with semantic and thus juridic modifications of the text.[10]: 74 These versions can be divided in three main groups: 1. the B version (alongside its 1847 and 1897 transcriptions) 2. the "Windward Islands" (Martinique and Guadeloupe) and Guyana versions, and 3. the "Saint-Domingue" versions; by far the most widespread in the 18th century and nowadays.[11]: 39 The Guadeloupe version of 1685 is considered the most authentic and trustworthy by Jean-François Niort and Jérémy Richard.[10]: 74–75

The title Code noir first appeared during the regency of Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, (1715–1723) under minister John Law, and referred to a compilation of two separate ordinances of Louis XIV from March and August 1685.[8] One of the two regulated black slaves in the French islands of the Americas, while the other established the Sovereign Council of Saint-Domingue.[5]

From the 18th century onward, the term Code noir was used not only to describe edits and additions to the original code, but also came to refer broadly to compilations of laws and other legal documents applicable to the colonies. Over time, the foundational ordinances and their associated texts were amended to meet the evolving needs of each colony.[5] Local modifications and additions to the Code noir (in the wide sense of the term) could be confirmed by the central government - but weren't always so. Thus sprouted local law on slavery answering local needs and solving the lacks of the 1685 Code noir.[11]: 40–41

Damas and Petit de Viévigne's "Ordonnance de police générale des Nègres et Gens de couleur libres" of December 25, 1783, which more or less corresponds the state of the law on its topic matter in Martinique and Guadeloupe just before the fall the Ancien régime, aimed to better enforce, explain, reiterate, modify and add to the Code noir. For example, the practice of letting Sunday off as a free day for slaves in exchange of them waiving their legal right to be fed ("Samedi-jardin") was now to be punished with a 500 livres fine (which it was not in the Code noir); the fine for abandoning an aged or infirm slave if they had to be placed in a hospital by the authorities was raised from the Code noir's standards; freemen keeping or fencing slaves were to be enslaved (and not fined) and slaves were also now prohibited from hiding escaped slaves under the threat of whipping and prison...[11]: 41–47

After the restitution of France's colonies in the Treaty of Amiens of 1802, slavery and the provisions of the Code noir were put back in place.[12] They were reinstated first in the restituted colonies of Martinique, Saint-Lucia and Tobago, and also the Mascarenes by the law of May 20, 1802;[13]: 31–33 in Guadeloupe by a consular decree on July 16, 1802;[13]: 36–37, [47,54,57] and in Guiana by consular decree on 7 December 1802.[12]: paragraph 48 The Code Noir coexisted for forty-three years with the Napoleonic code despite the contradictory nature of the two texts, but this arrangement became increasingly difficult due to the French Court of Cassation rulings on local jurisdictions' decisions following the 1827 and 1828 ordinances on civil procedures.[14] Due to the codification of the law, the ensuing legal dogmatism and need for legality, and the administrative and judicial centralisation, the Code noir was likely applicated with more rigor than in the time of the Ancien Régime.[15]: 249

According to historian Frédéric Charlin, in metropolitan France, "the two decades of the July Monarchy were characterized by a political trend to endow the slave with a certain level of humanity… [and to] encourage a slow assimilation of the slave into other workforces of French society through moral and family values". The jurisprudence of the Court of Cassation under the July Monarchy was marked by a gradual recognition of a legal personhood for slaves. Accordingly, the 1820s saw a general abolitionist trend, but one that was mainly preoccupied with a gradual emancipation that paralleled improved conditions for slaves.[14]

Summary

In the preamble of the Code noir, it is stated that it only applicates to the Islands of French America (in the Caribbean).[16]: 121

In 60 articles,[17] the document specified the following:

Legal status and incapacity of slaves

In the Code noir, the slave (of any race, color or gender) is considered property immune from seizure (article 44), yet also criminally liable (article 32). Article 48 stipulates that, in the case of a seizure of person (physical seizure), this is an exception to article 44.[17][8] Should the human nature of the slave confer certain rights, the slave was nevertheless denied a true civil personality before the reforms adopted under the July Monarchy. According to French colonial legal historian Frédéric Charlin, an individual's legal capacity was fully dissociable from her humanity under old French law.[18] Additionally, the legal status of slaves was further distinguished by the separation of field slaves (esclave de jardin), the main workforce, from domestic slaves "of culture" (esclave de culture).[19] Before the institution of the Code noir, slaves other than those "of culture" were considered fixtures (immeubles par destination). The new status was adopted with such great reluctance on the part of local jurisdictions that it was necessary for a ruling of the King's Council of 22 August 1687 to take a position on the capacity of slaves because of the rules of succession applicable to the new status.[18] Despite the 1804 creation of the Napoleonic Code and its partial promulgation in the Antilles, the re-institution of slavery in 1802 had led to the reinstatement of parts of Code noir which precluded Napoleonic rights.[18] In the 1830s, under the civil code of the July Monarchy, slaves were explicitly given a civil personality while also considered as being fixtures, that is, personal property legally attached to and/or part of real estate or businesses.[19]

The status of the slave in Code noir is legally different from that of a serf primarily in that serfs could not be bought. According to anthropological historian Claude Massilloux, it is the mode of reproduction that distinguishes slavery from serfdom: while a serf cannot be purchased, they reproduce through demographic growth.[20] In Roman law (the Digest), a slave could be sold, given away, and legally passed to another owner as part of an estate or a legacy, but this could not be done with a serf. Contrary to serfdom, slaves were considered in Roman law to be objects of personal property that could be owned, usufruct, or used as a part of a pledge. In general, a slave could be said to have a much more restricted legal capacity than does a serf, simply due to the fact that serfs were considered right-holding individuals whereas slaves, although recognized as human beings, were not. Swiss Roman law scholar Pahud Samuel explains this paradoxical status as "the slave being a person in the natural sense and a thing in the civil law sense".[21]

The Code noir provided that slaves might lodge complaints with local judges in the case of mistreatment or being under-provided with necessities (article 26), but also that their statements should be considered only as reliable as that of minors or domestic servants.[8]

Religion

- The Code noir encouraged that slaves be baptized and educated in the Apostolic and Roman Catholic religion (article 2).[5][8]

- The writers of the code believed that slaves of all races were human persons, endowed with a soul and receptive to salvation.[citation needed]

- Slaves were prohibited from publicly practicing any religion other than the Catholic, Apostolic, and Roman Catholic religion (article 3),

- Slaves were prohibited the practice of the Protestant faith (article 5) and particularly "pagan religions" practiced by indigenous Indians who were routinely forced into slavery in Mexico and the Americas. [citation needed]

- The code extends the punishment of pagan slave conventicles to masters who allowed pagan beliefs and practices performed by their slaves, thus encouraging quick indoctrination into Catholicism on threat of the outright punishment of lenient slave holders.[citation needed]

- Slaves had to be buried in consecrated ground if they were baptized (article 14).

Sexual relations, marriage, and progeny

- Weddings between slaves strictly required the master's permission (art. 10)

- Weddings also required the slave's own consent (art. 11)

- Children born to married slaves were also slaves, belonging to the female slave's master (art. 12)

- Children of a male slave and a free woman were free; children of a female slave and a free man were slaves (art. 13; compare partus sequitur ventrem)

- Sexual relationships between a free man and a female slave were deemed adulterous. A free man fathering children with a slave, and the slave's master who had allowed it to happen, were fined 2000 pounds of sugar. If the slave's master was the father, the slave and her children were confiscated and couldn't be freed, unless the master agreed to marry the slave, making her and her children free (art.9)

Maternal Impact

Code Noir acknowledged the existence of slave families and marriages. The Code recognized slaves marriages provided they were contracted according to the Catholic rite and attempted to regulate family life among slaves. Mothers played a central role in maintaining family structures, and the Code addressed issues related to the separation of families through sales or other means. The status of a child's freedom was dependent on the mother's status at the time of birth. Article XIII cites that "...if a male slave has married a free woman, their children, either male or female, shall be free as is their mother, regardless of their father's condition of slavery. And if the father is free and the mother a slave, the children shall also be slaves".

Article XII precises that "the children born in marriage to a male and a female slave will belong to the mother's master if they are owned by two different masters".[22][23] This reliance upon the mother's status for the identification of the consequent child's status placed the majority of the slave-producing burden upon the enslaved women of the French colonies.

Prohibitions

- Slaves must not carry weapons except with the permission of their masters for hunting (art. 15)

- Slaves belonging to different masters must not gather at any time under any circumstance (art. 16)

- Slaves who contravened to this article were at the very least whipped and branded, and could be sentenced to death by a judge in cases of recidivism. Masters had to compensate their neighbors for any damage suffered and had to pay a fine of ten crowns, to be doubled for a second offence

- Slaves should not sell sugar cane, even with permission of their masters (art. 18)

- Slaves who contravened to this article would be whipped, while consenting masters and the purchaser would be fined ten livres.

- Slaves should not sell any other commodity without permission of their masters (art. 19–21)

- Masters must give food (quantities specified) and clothes to their slaves, even to those who were sick or old (art. 22–27)

- Slaves under ten had to be given half the specified quantities

- The food could not be replaced by cane brandy.

- It was not allowed for slaves to obtain these supplies by working on their own behalf during some days of the week.

- Slaves couldn't work, nor be sold, on Sunday or on catholic's holy days. The penalty was the confiscation of the slave and of the product of his work (art. 6)

- Slaves could testify in court but their testimony couldn't be considered a proof or be the basis for a ruling (art.30)

- A slave who struck his or her master, his wife, his mistress, his mistress' husband or his master's/mistress's children with bruising, bloodshed or on the face would be executed (art. 33)

- 'Excess' (?) and assaults would be severely punished, if not by execution (art. 34)

- Slaves robbing (meaning, with the use of force, threat of force or use of fear) horses or cows would receive 'afflictive sentences', possibly execution (art. 35)

- Thievery of sheep, goats, pigs, poultry, sugar cane, millet and vegetables would be punished, depending on the thievery's specificities, by a judge, by whipping and branding (art. 36)

- It is important to note that these kinds of punishments (branding by iron, mutilation, etc.) also existed in metropolitan France's penological practice at the time.[25]

- The third attempt to escape was punishable by death (art. 38)

- A slave husband and wife and their prepubescent children under the same master were not to be sold separately (art. 47)

Punishments

- Fugitive slaves absent for a month should have their ears cut off and be branded. For another month their hamstring would be cut and they would be branded again. A third time they would be executed (art. 38)

- Free blacks who harboured fugitive slaves would be beaten by the slave owner and fined 300 pounds of sugar per day of refuge given; other free people who harboured fugitive slaves would be fined 10 livres tournois per day (art. 39)

- If a master had falsely accused a slave of a crime and as a result, the slave had been put to death, the master would be fined (art. 40)

- Masters might chain and beat slaves but might not torture nor mutilate them (art. 42)

- Masters or 'commandants' who killed their slaves would be prosecuted by agents of the law and punished (art. 43)

- However, in reality, the conviction of masters for the murder or torture of slaves was very rare.[citation needed]

- Slaves were community property and could not be mortgaged, and must be equally split between the master's heirs, but could be used as payment in case of debt or bankruptcy, and otherwise sold (art. 44–46, 48–54)

Punishments were a matter of public or royal law, where the disciplinary power over slaves could be considered more severe than that for domestic servants yet less severe than that for soldiers.

Freedom

- Slave masters 20 years of age (25 years without parental permission) could free their slaves (art. 55)

- Starting in the 18th century, manumission required authorization as well as the payment of an administrative tax. The tax was first instituted by local officials, but later affirmed by the edict of 24 October 1713 and the royal ordinance of 22 May 1775.[26]: 66

- Slaves who were declared to be sole legatees by their masters, or named as executors of their wills, or tutors of their children, should be considered as freed slaves (art. 56)

- Freed slaves had to show a special respect for their former master and were punished more severely for any offense against him. However, they were deemed free of any other obligation the former master could claim (art. 58)

- This principle was later deformed to impose harsher punishments on freemen who committed assault against whites, for the sake of maintaining the slaver regime.[27]: 368

- Freed slaves were French subjects, even if born elsewhere (art. 57)

- No naturalization records were required for French citizenship, even if the individual was born abroad

- The manumission certificate replaced the birth certificate in France.[27]: 376

- Freed slaves had the same rights as French colonial subjects (art. 58, 59)

- Fees and fines paid with regard to the Code noir must go to the royal administration, but one third would be assigned to the local hospital (art. 60)

Seizure and slaves as chattels

With respect to the inheritance of property, estate, and seizures, slaves were considered to be personal property (article 44), that is, considered separate from the estate on which they live (which was not the case with serfs). Despite this, slaves could not be seized by a creditor as property independent of the estate, with the exception of compensating the seller of the slaves (article 47).

According to the Code, slaves can be bought, sold, and given like any chattels. Slaves were provided no name or civil registration, rather, starting in 1839, they were given a serial number. Following the 1848 abolition of slavery under the French Second Republic, a name was assigned to each former slave.[28] Slaves could testify, have a proper burial (for those baptized), lodge complaint, and, with the master's permission, have savings, marry, etc. Nevertheless, their legal capacity was still more restrictive than that of minors or domestic servants (articles 30 and 31). Slaves had no right to personal possessions and could not bequeath anything to their families. Upon the death of the slave, all remained property of the master (article 28).

Married slaves and their prepubescent children could not be separated through seizure or sale (article 47).

Expulsion of the Jews

The first article of the Code noir enjoined a Catholic expulsion of all Jews residing in the colonial territories due to their being "sworn enemies of the Christian faith" (ennemis déclarés du nom chrétien), within three months under penalty of the confiscation of person and property. The Antillean Jews targeted by the Code noir were mainly descendants of families of Portuguese and Spanish origin who had come from the Dutch colony of Pernambuco in Brazil.[29][4]

After the Da Costa family founded the first synagogue of Martinique in 1676, the visible Jewish presence in Martinique and Saint-Domingue led Jesuit missionaries to petition for the expulsion of Jews and other non-Catholics to both local and metropolitan authorities.[30][2]

This precipitated an edict expelling Jews from the colonies in 1683, which would be incorporated into the Code Noir.[2] The Jewish population of Martinique was likely the specific target of the antisemitic clause (article 1) of the original 1685 Code.

The Code Noir in other French colonies

Two supplementary texts instituted the code in the Mascarene Islands and Louisiana;[5] they were ratified by King Louis XV in December 1723 and March 1724 respectively.[31] While they were essentially derived from the Code noir, these are distinct legislative texts, differing in content and in "spirit"; they were far more racialist and segregationist.[11]: 39–40

Mascarene Islands

The Code noir was introduced in the French colonies in the Indian Ocean (île de France and île de Bourbon; modern Mauritius and Réunion, respectively) by the Lettres patentes of 1723. The Lettres patentes were kept in place by the British after their annexation of Mauritius to ensure a better application of its protective clauses, and some of its provisions lasted until 1848. By virtue of their long lifespan, they are considered the fundamental legal texts for slavery in the region[32]: 112–113

The Mascarene Islands' Lettres patentes had 54 articles.[32]: 113 It notably differed from the Antilles' Code noir that slave owners, and not colonial authorities, were responsible for the Christianization of slaves.[33]: 467

The Lettres patentes were not exhaustive, and had to be supplemented if not amended by other texts; most notably, the royal ordinance of 20 August 1766, the local ordinance of September 1767, the Code jaune, the Code Decaen and the Nouveau Code Noir.[32]: 113–115

Louisiana

The Louisiana Code noir was ratified by King Louis XV in December 1723 and registered in New Orleans on September 10, 1724. It remained the basis of Louisiana's legislation on slavery (with some revisions in the Spanish Partidas Siete) until 1806-1807, when the legislature of New Orleans decided to revise the regulations on these matters. Even then, parts of the Code noir were kept.[34]: 21–22

The Louisiana Code noir had 54 articles, of which 31 were directly taken from the previous Code noir. The new articles generally offered minor changes, except the articles on marriage : whites were fully prohibited from contracting marriages with blacks.[16]: 121–122 Also, whereas punishment by whipping, branding or the cutting of the ears had to be confirmed by the Conseil supérieur in the Antilles' Code noir, they did not in the Louisiana Code noir (meaning the lower court, a trial court, could alone choose punishment for a slave)[16]: 189

Canada

The Code noir was not legally valid in Canada, be it the French West Indies' or Louisiana's,[16]: 43 and there were no specific rules on the treatment of slaves in royal edicts, ordinances, acts in public registries transcribed by the Conseil supérieur or Raudot's ordinance. However, owners generally complied with the Code noir without requirement to do so[16]: 122 , and slaves were still considered to be personal property.[16]: 85

Yet, the Code noir was not always followed to the letter. Corporal punishment was less severe.[16]: 178 In front of the court, slaves were generally treated equally to free persons - if not with leniency.[16]: 189–190, [178] Slaves could be the plaintiffs in civil cases.[16]: 189–190 Whereas slaves had no legal capacity in the Code noir, they could and often did act as witnesses in the Canada on the same footing as free persons.[16]: 179 For slaves to survive the harsh weather, they needed better clothing than the minimum prescribed by the Code noir.[16]: 127 There is at least one case of an owner taking only a portion of his slave's earnings (whereas according to the Code noir, he was entitled to all of it)[16]: 126

Legacy

Jean-François Niort controversy

Upon the 2015 release of his work Le Code noir. Idées reçues sur un texte symbolique, colonial law historian Jean-François Niort was attacked for his position that the authors of the Code intended for "a mediation between master and slave" by minor Guadeloupean political organizations self-styled as "patriotic" and accused of "racial discrimination" and denialism by some members of the Guadeloupean independentist movement who threatened to expel him from Guadeloupe.[35] He has been roundly supported by the historical community[who?] which has denounced the verbal and physical intimidation of specialists in the colonial history of the region.[36] The controversy continued in an argument in the opinions section of the French newspaper Le Monde between Niort and the philosopher Louis Sala-Molins.[37]

Repeal in 2025

On May 10, 2025, on the occasion of the National Day of Remembrance of the Slave Trade, Slavery, and Their Abolition, French Prime Minister François Bayrou promised to abolish the Black Code on slavery. The Senegalese historian Mansour AW criticized the effort as vain subtilities with no adherent, as slavery is already abolished and the Code noir is no longer in force.[38]

Further reading

- Palmer, Vernon Valentine (1996). "The Origins and Authors of the Code Noir". Louisiana Law Review. 56: 363–408.

See also

- History of slavery in Louisiana

- Slavery in the French West Indies

- Slavery in Canada

- Slavery in Haiti

- Slave codes

- Slave rebellions

- Black Codes

- Slave Trade Acts

- Panis

References

- ^ Stovall, p. 205.

- ^ a b c Breathett, George. "Catholicism and the Code Noir in Haiti". The Journal of Negro History, vol. 73, no. 1/4, Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc, 1988, pp. 1–11, doi:10.1086/JNHv73n1-4p1.

- ^ Jacques Le Cornec, "Un royaume antillais: d'histoires et de rêves et de peuples mêlés", on Google Books, L'Harmattan.

- ^ a b Lafleur, Gérard (1985). "Les juifs aux îles françaises du vent (XVIIe-XVIIIe siècles)" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe. 65–66 (65–66): 77–133. doi:10.7202/1043818ar.

- ^ a b c d e f Palmer, Vernon Valentine (1996). "The Origins and Authors of the Code Noir". Louisiana Law Review. 56: 363–408.

- ^ "The "Code Noir" (1685)" (PDF). 19 June 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2015. Retrieved 10 October 2022.

- ^ Breathett, George. "Catholicism and the Code Noir in Haiti". The Journal of Negro History, vol. 73, no. 1/4, Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, Inc, 1988, pp. 1–11.

- ^ a b c d e "Le Code noir de 1685". axl.cefan.ulaval.ca. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ^ a b Bellance, Hurard (2011). La police des Noirs en Amérique (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Guyane, Saint-Dominique) et en France aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles. Ibis rouge. p. 67. ISBN 978-2-84450-369-5.

- ^ a b Niort, Jean-François; Richard, Jérémy (2010). "L'Édit royal de mars 1685 touchant la police des îles de l'Amérique française dit « Code Noir » : Comparaison des éditions anciennes à partir de la version « Guadeloupe »". Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe (in French) (156): 73–89. doi:10.7202/1036845ar. ISSN 0583-8266.

- ^ a b c d Niort, Jean-François (2016). "De l'ordonnance royale de mars 1685 à l'ordonnance locale sur la police générale des Nègres de décembre 1783 : remarques sur le « Code Noir » et son évolution juridique aux Iles françaises du Vent sous l'Ancien Régime". Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe (in French) (173): 37–52. doi:10.7202/1036583ar. ISSN 0583-8266.

- ^ a b Pouliquen, Monique (2009), Hroděj, Philippe (ed.), "L'esclavage subi, aboli, rétabli en Guyane de 1789 à 1809", L'esclave et les plantations : de l'établissement de la servitude à son abolition. Hommage à Pierre Pluchon, Histoire (in French), Rennes: Presses universitaires de Rennes, pp. 241–263, ISBN 978-2-7535-6637-8, retrieved 8 August 2025

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ a b Niort, Jean-François; Richard, Jérémy (2009). "A propos de la découverte de l'arrêté consulaire du 16 juillet 1802 et du rétablissement de l'ancien ordre colonial (spécialement de l'esclavage) à la Guadeloupe". Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe (in French) (152): 31–59. doi:10.7202/1036868ar. ISSN 0583-8266.

- ^ a b Frédéric Charlin, « La condition juridique de l’esclave sous la Monarchie de Juillet : de l’homo servilis à l’homo civilis », https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01926560/document, 2010, p. 45

- ^ Carbonnier, Jean (2001). "Scolie sur le non-sujet du droit : L'esclavage sous le régime du Code Civil". Flexible droit (PDF) (in French) (10th ed.). Paris: Librairie Générale de Droit et de Jurisprudence. pp. 247–254. ISBN 978-2275020082.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Trudel, Marcel (2012). Canada's Forgotten Slaves : Two centuries of bondage. Translated by Tombs, George. Montréal, Québec: Véhicule Press. ISBN 9781550653274.

- ^ a b "The 60 articles of the Code Noir". Liceo Cantonale di Locarno. Archived from the original on 4 March 2007.

- ^ a b c Charlin, Frédéric (2010). "La condition juridique de l'esclave sous la Monarchie de Juillet". Revue française de théorie, de philosophie et de cultures juridiques: 45–74.

- ^ a b Castaldo, André (2010). "Les " Questions ridicules " : la nature juridique des esclaves de culture aux Antilles" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société d'Histoire de la Guadeloupe. 157: 56–62.

- ^ Meillassoux, Claude (1998). Anthropologie de l'esclavage. Paris: Quadrige. p. 90.

- ^ Pahud, Samuel (2013). "Le statut de l'esclave et sa capacité à agir dans le domaine contractuel" (PDF). Étude de droit romain de l'époque classique – via University of Lausanne Open Archives.

- ^ "Code noir". Archived from the original on 4 March 2007.

- ^ wfu.ares.atlas-sys.com https://web.archive.org/web/20231208230321/https://wfu.ares.atlas-sys.com/ares/ares.dll?SessionID=A054125445F&Action=10&Type=10&Value=62625. Archived from the original on 8 December 2023. Retrieved 23 April 2025.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ^ Recueil de l'Académie de législation de Toulouse. 1868.

- ^ "Le châtiment au Moyen Age". Histoires d'antan et d'à présent. Retrieved 30 May 2022.

- ^ Niort, Jean-François (January–April 2020). "Les libres de couleur dans la société coloniale ou la ségrégation à l'oeuvre (XVIIeXIXe siècles)" (PDF). Bulletin de la Société d'histoire de la Guadeloupe (131): 61–112. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 December 2023 – via Érudit.

- ^ a b Rogers, Dominique (6 December 1999). Les libres de couleur dans les capitales de Saint-Domingue : fortune, mentalités et intégration à la fin de l'Ancien Régime (1776-1789) (PhD thesis) (in French). Université Michel de Montaigne - Bordeaux III.

- ^ Gordien, Emmanuel (11 February 2013). "Les patronymes attribués aux anciens esclaves des colonies françaises. NON AN NOU, NON NOU, les livres des noms de familles antillaises". In Situ. Revue des patrimoines (in French) (20). doi:10.4000/insitu.10129. ISSN 1630-7305. S2CID 191475428.

- ^ Merrill, Gordon (1964). "The Role of Sephardic Jews in the British Caribbean Area during the Seventeenth Century". Caribbean Studies. 4 (3): 32–49. JSTOR 25611830.

- ^ Maurouard, Elvire. Juifs de Martinique et Juifs Portugais sous Louis XIV. Éditions Du Cygne, 2009.

- ^ Library of Congress. "The Code Noir". The Library of Congress Global Gateway. Archived from the original on 24 October 2005. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ a b c Benoiton, Laurent (2010). "Le droit de l'esclavage à l'île Bourbon: un exemple d'"antidroit"". Revue juridique de l'Océan Indien (11): 111–122 – via HAL open science.

- ^ Larson, Pier M. (2007). "Enslaved Malagasy and 'Le Travail De La Parole' in the Pre-Revolutionary Mascarenes". The Journal of African History. 48 (3): 457–479. doi:10.1017/S0021853707002824. ISSN 0021-8537. JSTOR 40206590.

- ^ Everett, Donald E. (1966). "Free Persons of Color in Colonial Louisiana". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 7 (1): 21–50. ISSN 0024-6816. JSTOR 4230881.

- ^ dahomay, jacky (6 April 2015). "Dénonçons la fatwa contre Jean-François Niort". Mediapart (in French). Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ Creoleways, Rédac (10 April 2015). "Code Noir : Jean-François Niort menacé, les historiens de Guadeloupe font bloc contre la censure". Creoleways (in French). Archived from the original on 18 January 2022. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Le Code Noir, une monstruosité qui mérite de l'histoire et non de l'idéologie". Le Monde.fr (in French). 15 September 2015. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Le code noir bientôt abrogé". dw.com (in French). 27 May 2025. Retrieved 2 June 2025.

External links

- Le code noir ou Edit du roy (in French). Paris: Chez Claude Girard, dans la Grand'Salle, vis-à-vis la Grande'Chambre. 1735.

- Édit du Roi, Touchant la Police des Isles de l'Amérique Française (Paris, 1687), 28–58. [1]

- Le Code noir (1685) [2] Archived 9 July 2005 at the Wayback Machine

- The "Code Noir" (1685) (in English), trans. John Garrigus

- Tyler Stovall, "Race and the Making of the Nation: Blacks in Modern France." In Michael A. Gomez, ed. Diasporic Africa: A Reader. New York: New York University Press. 2006.

- "Slavery". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Archived from the original on 29 November 2011. Retrieved 7 November 2016.