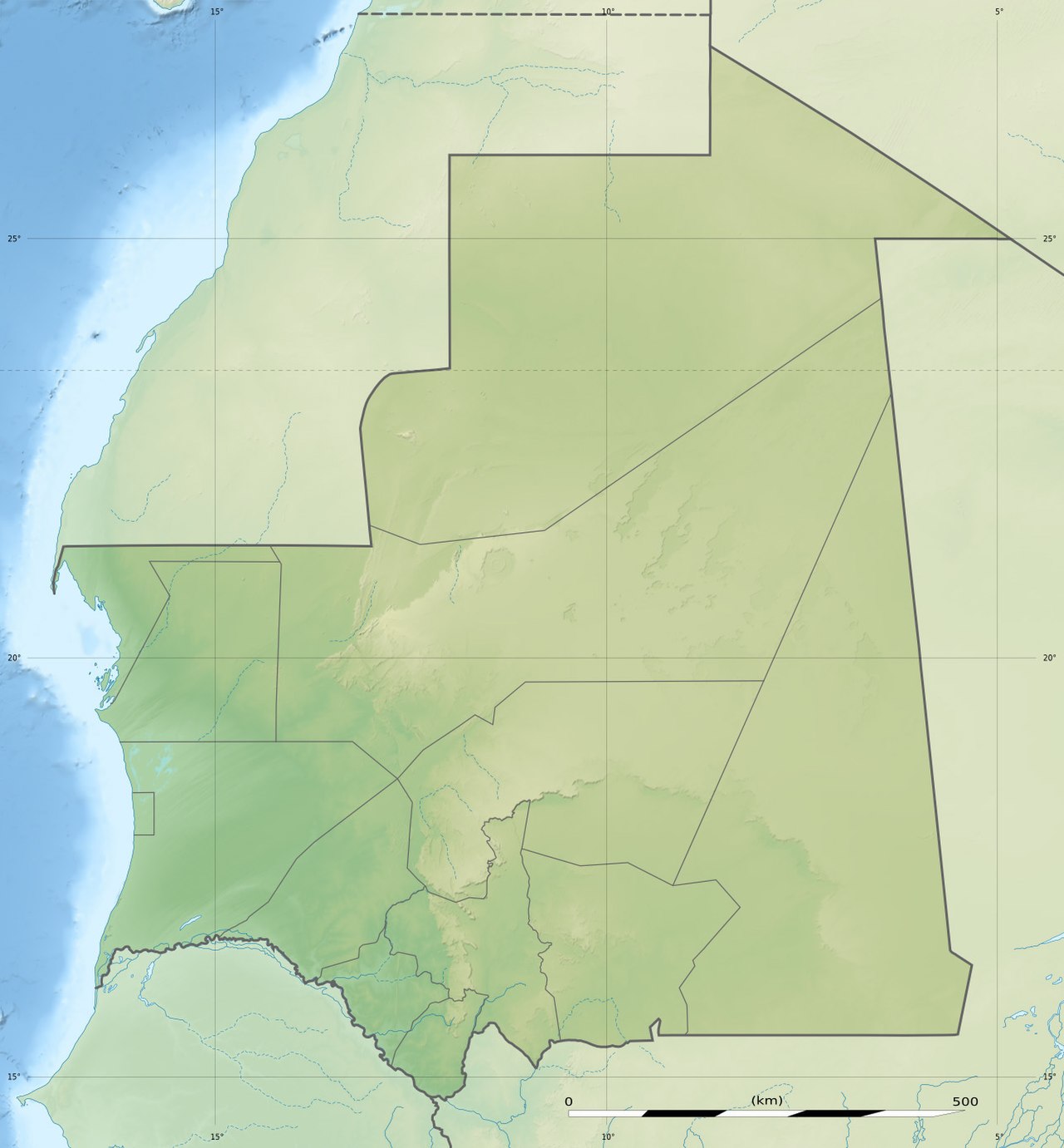

Dhar Tichitt is a Neolithic archaeological site located in the southwestern region of the Sahara Desert, in Mauritania. It is one of several settlement locations along the sandstone cliffs in the area. Dhar Tichitt, Dhar Walata, Dhar Néma, and Dhar Tagant are the sites which compose Tichitt culture.The cliffs were inhabited by farmers and pastoralists starting at around 4500 BP and lasted to around 2300 BP, or approximately 2500 to 500 BCE. This area is one of the oldest known archaeological occupation sites in the western part of Africa. About 500 stone settlements littered the region in the former savannah of the Sahara. In addition to herding livestock (e.g., cattle, sheep, goats), its inhabitants hunted, fished, collected wild grain, and grew bulrush millet. The inhabitants and creators of these settlements during these periods thought to have been ancestors of the Soninke people.

| Dhar Tichitt | |

|---|---|

| Location | Mauritania |

| Coordinates | 18°27′06″N 9°24′19″W / 18.4517°N 9.40528°W |

Dhar Tichitt is a line of sandstone cliffs located in the southwestern region of the Sahara Desert in Mauritania that boasts a series of eponymous Neolithic archaeological sites. It is one of several in the area belonging to the Tichitt culture, including Dhar Tichitt, Dhar Walata, Dhar Néma, and Dhar Tagant.[1] Dhar Tichitt, which includes Dakhlet el Atrouss, may have served as the primary regional center for a hierarchical social structure within the Tichitt Tradition.[2] The cliffs of Dhar Tichitt were inhabited by pastoralists and farmers between 4000 BP and 2300 BP,[3] or between 2000 BCE and 300 BCE.[4][5]

Dhar Tichitt is one of the oldest known archaeological occupation sites in West Africa. About 500 settlements littered the region in the former savannah of the Sahara. In addition to herding livestock (cattle, sheep, goats), its inhabitants hunted, fished, collected wild grain, and grew bulrush millet. The inhabitants and creators of these settlements during these periods are thought to have been ancestors of the Soninke people. Plateau settlements consisted of multiple drystone-compounds containing houses and granaries (or "storage facilities"), sometimes with "street" layouts, which were constructed between c. 1400 BCE and 300 BCE.[6] Large livestock enclosures were erected in proximity of some sites. And around some settlements, larger common stone "circumvallation walls" were built, suggesting that "special purpose groups" cooperated as a result of decisions "enforced for the benefit of the community as a whole."[7][8]

Geography and climate

Dhar Tichitt and the surrounding areas are characterized by steep sandstone cliffs (the word dhar meaning escarpment in Hassaniya Arabic,[9] sandy flats with scattered clumps of coarse grasses, and interdunal depressions.[10][11] Today, the climate of the Dhar Tichitt region today is arid and hot, with it only experiencing about 100 millimeters of rain per year.[11] However, in the past the area was much more temperate. Paleoclimatic data shows that there were three separate phases of significant humidity occurring during the Holocene period, one from 10,000 to 7,000 BP, another from 5,000 to 3,000 BP, and a more subtle episode at around 2,000 BP.[10] During the middle humid phase, referred to in Mauritania as the Nouakchottian, the region experienced two different seasons per year, a dry season and a shorter rainy season. These humid phases would have made it possible for moisture to accumulate in the sandy flats, leading to small lakes forming in the interdunal depressions of the region. Around 2,500 BP, as the climate began to change into an increasing pattern of desertification, it is thought that people were forced out of the region.[10]

Archaeological findings

Initial excavations

The site was first extensively excavated by Patrick Munson in the late 1960s, with him publishing a detailed description of the sites in 1971.[9] Munson determined an archeological sequence which he deemed to have existed entirely during the Neolithic period. He divided the site into eight discreet temporal phases based on the artifacts, architecture, and locations in the area. These periods were named, in chronological order, as follows: Akreijit, Khimiya, Goungou, N'Khall, Naghez, Chebka, Arriane, and Akjinjeir.[11]

In the Akreijit deposit, his excavation discovered various microliths of diverse size and purpose, scrapers, projectile points, quartz pebbles and cores, milling stones, and a particular ceramic pottery culture. The Khimiya phase yielded a larger amount of pottery, although a significant portion of it was of the same variety as the Akreijit layer. The most notable contents of the Khimiya phase were the huge number of fish and shellfish remains, as well as other aquatic cultures; this deposit indicated that the people of this time were extensively using the lakes in the region. The Goungou layer yielded largely similar pottery and lithic culture to that of the Khimiya, while the N'Khall only contained a small amount of unique lipped jars in a different stratigraphical layer.[11]

The Naghez layer showcases a major departure from the previous phases, since the sites contain precise stone-masonry constructions which measured 20 to 40 meters in diameter. These compounds appear to have been walled and fortified. Although the ceramic culture remained constant in this period, there was a change with the newfound presence of large amounts of non-portable milling stones. The Chebka period had the same level of architectural complexity, with the only major difference being the placement of the sites. The Chebka and later sites did not appear to contain any evidence for aquatic fauna, which may point to the advancement of desertification.[11]

The last two periods, Arriane and Akjinjeir, are characterized by their much smaller and more compact sites. Both the Arriane and Akjinjeir phases still appeared to have some level of walls, albeit no real fortifications. The lithic and ceramic cultures found at the site were much less diverse and not aesthetically-driven as some of the previously dated artifacts were.[11]

Subsequent excavations

Throughout the late 1970s and early 1980s, various archaeological expeditions took place to thoroughly excavate and document the Dhar Tichitt site, with most of these efforts largely focused on sites with stone architecture that were associated with the peak of the architecture. Studies led by archaeologists, many of them French, such as Hugot, Delneuf, Beyries, Amblard, Holl, and Roux explored the architecture, ceramics, rock engravings, lithics, and possible economies at the site.[10]

In the field seasons of 1980 and 1981, a large number of animal bone fragments and samples were found. These included domesticated animals such as cows, sheep, goats, and camels as well as a wide variety of wild animals ranging from aquatic animals like hippopotami to desert antelope like the Addax.[10]

Between 1980 and 1983, a limited amount of botanical evidence was also found. The majority of this data was gathered from the impressions of grain left behind on ceramic potsherds, although some remains of seeds and grains were also present at the sites. Of the half dozen species of plants found at the site, Pennisetum or bulrush millet was the only domesticate found. Some wild grains and fruits also represent a small amount of the botanical evidence present at the site.[10] Carnelian and amazonite beads, as well as stone-arm rings and axes have been found in association with the site, and these objects are known to represent at least some level of long-distance trade.[12] Further excavations of the earliest layer of desposition yielded eight ostrich eggshell beads and a pierced bone disc.[13] Only one fragment of an iron slag has been discovered from the site and was dated to the Late Tichitt period, possibly indicating the presence of metallurgy in the latter part of this site's habitation.[13]

In 1980, the first aerial survey of the site was performed via low altitude photographic coverage. This method allowed archaeologists to collect data regarding the placement of the stone structures in relation to each other by studying site morphology as well as topographical location.[10]

-

Stone axes from Dhar Tichitt

-

Grinding stone

-

Pottery

-

Rock art

-

Tichitt Tradition drystone tumulus

Recent research

Essentially all of the major sites related to Dhar Tichitt had been thoroughly excavated during the 1980s. Later efforts in the 1990s and 2000s were much more focused on analyzing lithics and pottery, as well as formulating hypotheses for the socioeconomic strategies of the inhabitants.[14] Significant progress has taken place in research necropolises and tumuli located in and around these sites in order to decipher the culture's potential funerary perspectives. Furthermore, new excavations have taken time to reconstruct the climactic changes which resulted in the demise of this population center.

Significance and interpretations

This site is considered a Neolithic site. The Neolithic period in Africa (sometimes referred to as the Pastoral Neolithic) is marked by a change from hunter-gatherer lifestyles towards agricultural or pastoralist ones. Patrick Munson hypothesized that the Dhar Tichitt region was inhabited by pastoralists around 4500 BP, and it likely reached its population and cultural peak during this period. He also believed that the 4500 to 4000 BP date range of most significant occupation corresponded well with the Mid-Holocene humid period.[11]

Chronology

Munson's original interpretation with eight distinct phases was thoroughly refuted and reformatted by later archaeologists after more analysis of the recovered materials. Following analysis by Holl, Amblard, and MacDonald the chronology of the site were reorganized as follows:[15][16]

- Pre-Tichitt (Phase I, Akreijit): 2600 to 1900 BCE. Mobile hunter-gatherers and herders living in temporary campsites.

- Early Tichitt (Phase II and III, Khimiya and Goungou): 1900 to 1600 BCE. Initial cultivation of domesticated pearl millet. Considerable degree of mobility.

- Classic Tichitt (Phases IV-VI, N'Khall, Naghez, and Chebka): 1600 to 1000 BCE. Development of settlements comprising clusters of stone-walled compounds.

- Late Tichitt (Phases VII and VIII, Arriane and Akjineir): 1000 to 400 BCE. Period of intense aridification and demographic decline in the Tichitt-Oualata region.

The majority of expert on this site agree with dividing the chronology into either three or four periods. However, there is some level of pushback from one of the leading archaeologists at the site, Sylvie Amblard-Pison, who does not believe that the current data is able to represent an accurate chronology.[17] Overall, the chronology at the site is contentious, especially due to the spatial separation across a large space which makes it difficult to determine relative stratigraphy.

Agriculture

The first evidence for domestication of grain in the Dhar Tichitt region came from impressions in of grain on potsherds found by Patrick Munson's excavation. These impressions demonstrated that millet (Pennisetum glaucum) had been domesticated in the region.[18] Further analysis has demonstrated that the crop had been fully domesticated by at least 1100 BCE, but it likely occurred significantly before this.[15] The original investigation put forth by Munson hypothesized that the people associated with this site had likely become sedentary as a result of decreasing rain over the period of hundreds of year. Due to the lack of water, wild grains could no longer be gathered on a reliable basis. Thus, people begun settling down in communities adjacent to isolated pockets of moisture (oases) and practicing agriculture.[19] At the same time, some interpretations have concluded that during the dry season, wild grains and fruits were collected in the lowlands to supplement the otherwise pastoralist diet.[10] Thus, there is evidence for variance in diet during different seasons, with the millet forming a staple crop that was cultivated during the wet season while other wild sources of food that grew relatively well on sandy soils providing a supplementary food reservoir.[10]

Since the 1990s, research on the potsherd impressions has become more thorough. More recent dating using accelerated mass spectrometry has resulted in a newly calculated date of around 1900 to 1700 BCE for the domestication of millet, which aligns the emergence of agriculture with the Early Tichitt period.[20] Interestingly, the Tichitt culture was not unique in its domestication of millet, with some estimates placing domestication in associated Sahelian regions at around 2500 to 2000 BCE.[21] In fact, it has been suggested that domestication was taking place as early as the fourth millennium BCE.[22] It is likely that grain domestication in Dhar Tichitt was part of a much larger movement across the Sahel. Moreover, the evidence for material culture changes between the Pre-Tichitt and Early Tichitt periods appears to suggest that people started to farm millet more intensively around this time.[15]

Pastoralism

Much of the archeological data associated with the Pre-Tichitt period points to a relatively simple and widespread pastoralist economy incorporating herding of cows, sheep, and goats with hunting of antelope and freshwater fish.[13] Initially, Munson viewed the Pre-Tichitt period as being characterized by mobile pastoralists and a complete lack of agricultural developments. Despite the lack of evidence for cereal domestication during this period, it is now thought that pastoralism was likely practiced at the same time as millet agriculture for a significant period of time prior to the Early Tichitt period.[13] Some interpretations suggest that as the Tichitt culture was arriving en-masse into the region that is now Southeastern Mauritania, they had already formed a concrete culture characterized by agro-pastoralism.[23] This pastoral tradition persisted in the area far beyond the fall of the Tichitt culture; many Fulbe clans claim to have originally come from the Dhar Tichitt area, which they called 'Maasina' and became the namesake of the Sultanate of Massina, the Massina Empire and the modern town of Ke Macina in Mali.[24]

Social structure

Many of the societies of the Sahelian West Africa region are defined by organization into compounds, which encompass a given kinship group's material possessions.[9] The presence and roles of elites in the Dhar Tichitt has been a point of much debate amongst archeologists. There is very limited evidence for imported materials into the region, which some have taken to be proof that there was a long-distance trading network that was only accessible to the elites of the society.[4] However, it was also suggested that such scarce evidence could not be used to make conclusions about how the socioeconomic system of Tichitt was organized.[25]

Several factors point to the idea that households at the site had socioeconomic differentiation. The massive stone compounds that have come to define the site in the Classical Tichitt period are known to have served as dividers for social space. Different spaces within these compounds housed different classes of workers.[11] The settlements also appear to show the presence of multi-tiered hierarchies. The household compound units were characterized by different types of grinding stones that were likely used for different facets of food processing and tool-making.[11] Not every dwelling unit was equipped with the exact same set of grinding stones, which likely points to the fact that different households were focused on different types of production.[11] Furthermore, each household appears to have contained at least one male and one female member, with many of the compounds probably having a large family unit suitable for their agro-pastoralist lifestyle.[11] The clustering of funerary tumuli is known to have occurred only at certain places within the site, such as Dakhlet el Atrouss I. The overall settlement at Dhar Tichitt can be divided into four distinct tiers including hamlets (2 ha), villages (less than 10 ha), district centers (15 ha), and regional centers (80 ha).[26] It is thought that each of these district centers was capable of managing up to 20 different hamlets.[15] For most of the Classical compound clusters, large areas outside of the walled compounds were adjacent to the living quarters that are thought to have been used for maintaining livestock or gardens.[15] Research on the funerary tumuli of the site has been limited thus far, but experts believe that the larger presence of tumuli at this site indicates the possibility of it being an important cultural site. It is also possible that Dhar Tichitt represents a ritualistically important center given its unproportionally large number of tumuli that is not seen in any other sites within the associated Tichitt culture.[15] Interestingly, the large stone walls at the Dhar Tichitt site appear to be designed for spatial division, rather than defensive walls for outside attackers.[4] Some experts have speculated that Dhar Tichitt's unique system of social organization is indicative of a heterarchical organization system as seen in Jenné-jeno.[27] Moreover, the increased the diversity in decoration and pottery types as the culture transitioned into Dhar Tichitt may have been related to specialization.[28]

Ties to Middle Niger

Many archeologists have hypothesized a connection between the Dhar Tichitt and the overarching Middle Niger River Delta cultures such as the Ghana Empire. Both archeological and linguistic evidence shows that the Soninke people associated with the Ghana Empire are descendants of the remnants of the Tichitt culture following its collapse.[29] Most of the archeological evidence has come in the form of ceramics, cattle remains, and stonework present on the Northern border of the known Middle Niger boundaries. The earliest Tichitt assemblages present in this region have been dated to around 1300 BCE at the Saberi Faita site.[15] Thus, the presence archeological evidence seems to point to the Tichitt diaspora as being directly related to the later emergence of Middle Niger cultures in the first millennium BCE.[15]

Collapse

Both the change in climate (desertification of the Sahel) and influence of nomadic groups such as the Berbers are seen as plausible causes for the collapse of the Tichitt culture. Munson formulated the hypothesis that the Berbers arrived in the first millennium BCE on the basis of local rock art.[30] Violent conflicts with Berbers may have contributed to the fall of this society. Moreover, the Berber influences may be present in the material culture of the Late Tichitt period.[13] Sites such as Dhar Nema show the sudden presence of metallurgy, which were not associated with any of the previous Tichitt culture sites. Some suggest Berbers may have brought metal-making culture into the region, but also state that, "the major difficulty for testing this hypothesis is that so little is known about Berber metallurgy, its technology and its antiquity." Berbers are thought to have displaced many of the original inhabitants of the area, who then gradually moved into the northern Middle Niger River Valley.[13]

References

- ^ Sterry, Martin; Mattingly, David J. (26 March 2020). "Pre-Islamic Oasis Settlements in the Southern Sahara". Urbanisation and State Formation in the Ancient Sahara and Beyond. Cambridge University Press. p. 318. doi:10.1017/9781108637978.008. ISBN 978-1-108-49444-1. OCLC 1128066278. S2CID 243375056.

- ^ Linares-Matás, Gonzalo J. (13 April 2022). "Spatial Organization and Socio-Economic Differentiation at the Dhar Tichitt Center of Dakhlet el Atrouss I (Southeastern Mauritania)". African Archaeological Review. 39 (2): 167–188. doi:10.1007/s10437-022-09479-5. ISSN 1572-9842. OCLC 9530792981. S2CID 248132575.

- ^ Holl, Augustin F. C. (2009-08-01). "Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania (ca. 4000–2300 BP)". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. Histoire climatique des déserts d'Afrique et d'Arabie. 341 (8): 703–712. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2009.04.005. ISSN 1631-0713.

- ^ a b c Holl, Augustin (1985). "Background to the Ghana empire: Archaeological investigations on the transition to statehood in the Dhar Tichitt region (mauritania)". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 4 (2): 73–115. doi:10.1016/0278-4165(85)90005-4. ISSN 0278-4165.

- ^ Holl, Augustin F. C. (2002). "Time, Space, and Image Making: Rock Art from the Dhar Tichitt (Mauritania)". African Archaeological Review. 19 (2): 75–118. doi:10.1023/A:1015479826570. hdl:2027.42/43991. S2CID 54741966.

- ^ Challis, Sam; et al. (2005). "Funerary monuments and horse paintings: A preliminary report on the archaeology of a site in the Tagant region of South East Mauritania - Near Dhar Tichitt". The Journal of North African Studies. 10 (3): 459–470. doi:10.1080/13629380500336821.

- ^ Holl, Augustin (August 2009). "Coping with uncertainty: Neolithic life in the Dhar Tichitt-Walata, Mauritania, ( ca. 4000–2300 BP)". Comptes Rendus Geoscience. 341 (8–9): 703–712. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2009.04.005.

- ^ Hall A (1985). "Background to the Ghana Empire: archaeological investigations on the transition to statehood in the Dhar Tichitt region (Mauritania)". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 4 (2): 108. doi:10.1016/0278-4165(85)90005-4.

- ^ a b c Linares-Matás, Gonzalo J. (2022-06-01). "Spatial Organization and Socio-Economic Differentiation at the Dhar Tichitt Center of Dakhlet el Atrouss I (Southeastern Mauritania)". African Archaeological Review. 39 (2): 167–188. doi:10.1007/s10437-022-09479-5. ISSN 1572-9842. S2CID 254182626.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Holl, Augustin (1985). "Subsistence patterns of the Dhar Tichitt Neolithic, Mauritania". The African Archaeological Review. 3 (1): 151–162. doi:10.1007/bf01117458. ISSN 0263-0338. S2CID 162041986.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Munson, P. J. (1971). The Tichitt Tradition: A late prehistoric occupation of the southwestern Sahara. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

- ^ Atherton, John (June 1986). "Tichitt-Walata (R.I. Mauritanie): Civilisation et Industrie Lithique. Sylvie Amblard". American Anthropologist. 88 (2): 498–499. doi:10.1525/aa.1986.88.2.02a00620. ISSN 0002-7294.

- ^ a b c d e f MacDonald, Kevin C.; Vernet, Robert; Martinón-Torres, Marcos; Fuller, Dorian Q. (April 2009). "Dhar Néma: from early agriculture to metallurgy in southeastern Mauritania". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 44 (1): 3–48. doi:10.1080/00671990902811330. ISSN 0067-270X. S2CID 111618144.

- ^ Linares Matás, Gonzalo J. (2023-06-01). "Memory, agency, and labor mobilization in the monumental funerary landscapes of southeastern Mauritania, West Africa". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 70 101488. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2023.101488. ISSN 0278-4165. S2CID 256771770.

- ^ a b c d e f g h MacDonald, Kevin C. (2015), Goucher, Candice; Barker, Graeme (eds.), "The Tichitt tradition in the West African Sahel", The Cambridge World History: Volume 2: A World with Agriculture, 12,000 BCE–500 CE, The Cambridge World History, vol. 2, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 499–513, ISBN 978-0-521-19218-7, retrieved 2023-04-20

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Linares-Matás, Gonzalo J. (2022). "Spatial Organization and Socio-Economic Differentiation at the Dhar Tichitt Center of Dakhlet el Atrouss I (Southeastern Mauritania)". African Archaeological Review. 39: 167–188. doi:10.1007/s10437-022-09479-5.

- ^ Amblard-Pison, Sylvie (2014-12-15). "Entre sables et pierres: s'alimenter et boire dans les villages néolithiques d'une zone refuge saharienne de Mauritanie sud-orientale". Afriques (5). doi:10.4000/afriques.1496. ISSN 2108-6796.

- ^ Vernet, R. (1979), "La préhistoire de la Mauritanie", Introduction à la Mauritanie, Institut de recherches et d'études sur les mondes arabes et musulmans, pp. 17–44, doi:10.4000/books.iremam.1222, ISBN 978-2-222-02402-6

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ Munson, Patrick J. (1976-12-31), "Archaeological Data on the Origins of Cultivation in the Southwestern Sahara and Their Implications for West Africa", Origins of African Plant Domestication, De Gruyter Mouton, pp. 187–210, doi:10.1515/9783110806373.187, ISBN 978-90-279-7829-5

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link) - ^ K. Manning et al., '4500-year-old domesticated pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) from the Tilemsi valley, Mali: new insights into an alternative cereal domestication pathway', Journal of Archaeological Science, 38 (2011), 312–22.

- ^ Allsworth-Jones, Philip, ed. (2010). West African Archaeology: New developments, new perspectives. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. doi:10.30861/9781407307084. ISBN 978-1-4073-0708-4.

- ^ Fuller, Dorian Q.; Barron, Aleese; Champion, Louis; Dupuy, Christian; Commelin, Dominique; Raimbault, Michel; Denham, Tim (June 2021). "Transition From Wild to Domesticated Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum) Revealed in Ceramic Temper at Three Middle Holocene Sites in Northern Mali". African Archaeological Review. 38 (2): 211–230. doi:10.1007/s10437-021-09428-8. ISSN 0263-0338. PMC 8550313. PMID 34720323.

- ^ Person, Alain; Saoudi, Nour E.; Amblard, Sylvie (1995). "Nouvelles recherches, objectifs et premiers résultats sur le paléoenvironnement holocène des sites archéologiques de la région des Dhars Tichitt et Oualata (Mauritanie sud-orientale)". Journal des africanistes. 65 (2): 9–29. doi:10.3406/jafr.1995.2428. ISSN 0399-0346.

- ^ Kane, Oumar (2004). La première hégémonie peule. Le Fuuta Tooro de Koli Teηella à Almaami Abdul. Paris: Karthala. p. 90. Retrieved 1 April 2025.

- ^ McIntosh, Susan Keech; McIntosh, Roderick J. (March 1988). "From stone to metal: New perspectives on the later prehistory of West Africa". Journal of World Prehistory. 2 (1): 89–133. doi:10.1007/bf00975123. ISSN 0892-7537. S2CID 162413016.

- ^ Gibson, Catriona (June 1996). "Katina T. Lillios (ed.). The origins of complex societies in late prehistoric Iberia. (International Monographs in Prehistory Archaeological Series 8.) viii+183 pages, 82 illustrations, 10 tables. 1995. Ann Arbor(MI): International Monographs in Prehistory; 1-879621-19-3 hardback $39.50". Antiquity. 70 (268): 478–480. doi:10.1017/s0003598x00083551. ISSN 0003-598X. S2CID 163329826.

- ^ Haour, Anne (November 2001). "Susan Keech Mcintosh (ed.), Beyond Chiefdoms: pathways to complexity in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999, 176 pp., £40.00, ISBN 521 63074 6". Africa. 71 (4): 694–695. doi:10.3366/afr.2001.71.4.694. ISSN 0001-9720. S2CID 142213180.

- ^ MacDonald, K.C. (2011-04-01). "Betwixt Tichitt and the IND: the pottery of the Faïta Facies, Tichitt Tradition". Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa. 46 (1): 49–69. doi:10.1080/0067270X.2011.553485. ISSN 0067-270X. S2CID 161938622.

- ^ Capuzzo, Giacomo; Barceló, Juan Antonio (2015-06-05). "Cultural changes in the second millennium BC: a Bayesian examination of radiocarbon evidence from Switzerland and Catalonia". World Archaeology. 47 (4): 622–641. doi:10.1080/00438243.2015.1053571. ISSN 0043-8243. S2CID 162617517.

- ^ Munson, Patrick J. (October 1980). "Archaeology and the prehistoric origins of the Ghana empire". The Journal of African History. 21 (4): 457–466. doi:10.1017/s0021853700018685. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 161981607.