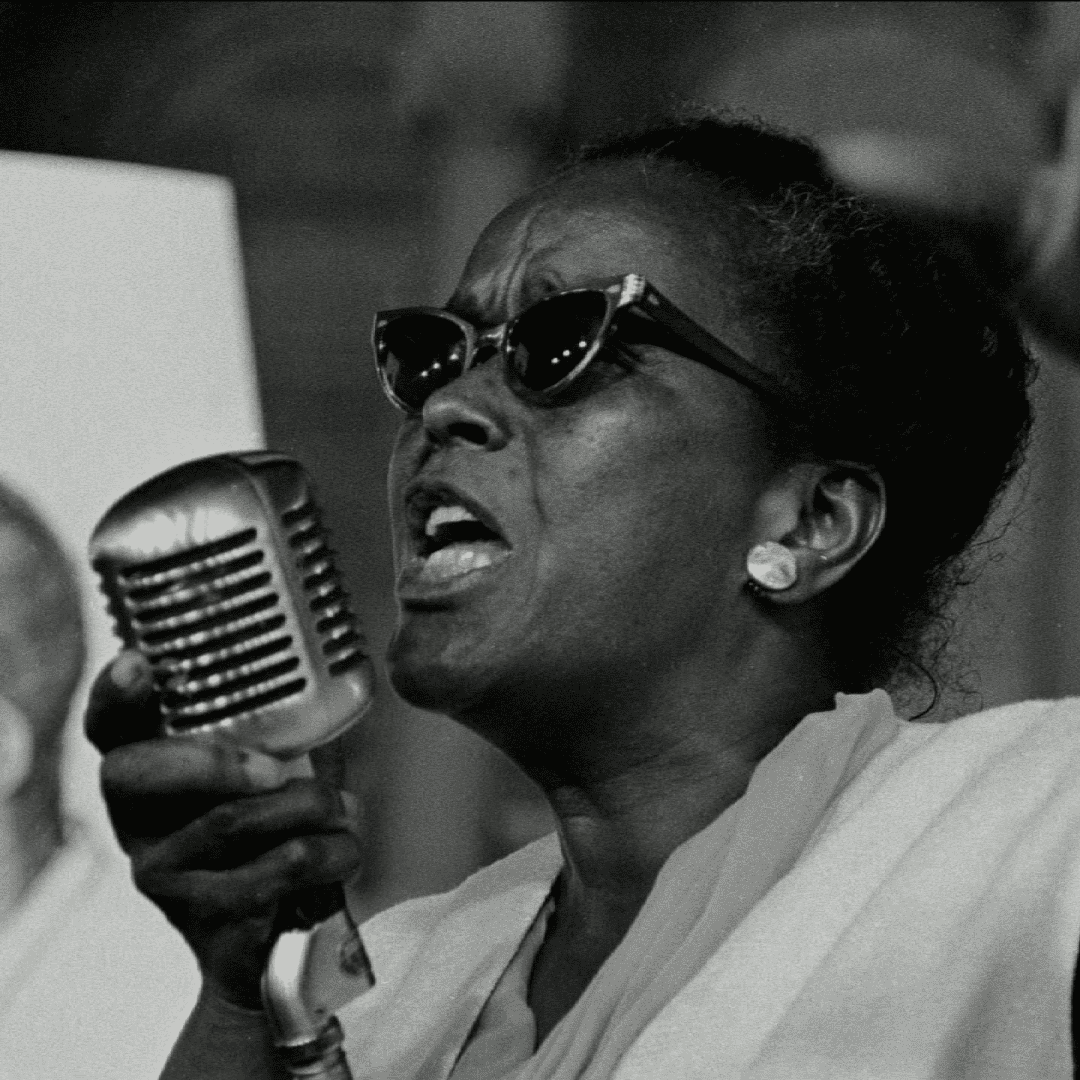

Ella Josephine Baker (December 13, 1903 – December 13, 1986) was an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and the South, she worked alongside some of the most noted civil rights leaders of the 20th century, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr. She also mentored many emerging activists, such as Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael, and Bob Moses, as leaders in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).

Ella Baker | |

|---|---|

Baker c. 1944 | |

| Born | Ella Josephine Baker December 13, 1903 Norfolk, Virginia, U.S. |

| Died | December 13, 1986 (aged 83) New York City, New York U.S. |

| Education | Shaw University (BA) |

| Organizations |

|

| Movement | Civil rights movement |

| Spouse |

Bob Roberts

(m. 1938; div. 1958) |

Ella Josephine Baker (December 13, 1903 – December 13, 1986) was an African-American civil rights and human rights activist. She was a largely behind-the-scenes organizer whose career spanned more than five decades. In New York City and the South, she worked alongside some of the most noted civil rights leaders of the 20th century, including W. E. B. Du Bois, Thurgood Marshall, A. Philip Randolph, and Martin Luther King Jr. She also mentored many emerging activists, such as Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael, and Bob Moses, as leaders in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).[1][2]

Baker criticized professionalized, charismatic leadership; she promoted grassroots organizing, radical democracy, and the ability of the oppressed to understand their worlds and advocate for themselves.[3] She realized this vision most fully in the 1960s as the primary advisor and strategist of the SNCC.[1][4] Biographer Barbara Ransby calls Baker "one of the most important American leaders of the twentieth century and perhaps the most influential woman in the civil rights movement".[4] She is known for her critiques of both racism in American culture and sexism in the civil rights movement.[5][6][7][8]

Early life and education

Ella Josephine Baker was born on December 13, 1903, in Norfolk, Virginia,[9] to Georgiana (called Anna) Blake Baker, and first raised there. She was the second of three surviving children, bracketed by her older brother Blake Curtis and younger sister Maggie.[10] Her father worked on a steamship line that sailed out of Norfolk, and so was often away. Her mother took in boarders to earn extra money. In 1910, Norfolk had a race riot in which whites attacked black workers from the shipyard. Her mother decided to take the family back to North Carolina while their father continued to work for the steamship company. Ella was seven when they returned to her mother's rural hometown near Littleton, North Carolina.[11]

As a child, Baker grew up with little influence.[12] Her grandfather Mitchell had died, and her father's parents lived a day's ride away.[11] She often listened to her grandmother, Josephine Elizabeth "Bet" Ross, tell stories about slavery and leaving the South to escape its oppressive society.[13] At an early age, Baker gained a sense of social injustice, as she listened to her grandmother's horror stories of life as an enslaved person. Her grandmother was beaten and whipped for refusing to marry an enslaved man her owner chose,[14] and told Ella other stories of life as an African-American woman during this period. Giving her granddaughter context to the African-American experience helped Baker understand the injustices black people still faced.[15]

Ella attended Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina, and graduated with valedictorian honors.[9] Decades later, she returned to Shaw to help found SNCC.[12]

Early activism

First efforts (1930–1937)

Baker worked as editorial assistant at the Negro National News. In 1930, George Schuyler, a black journalist and anarchist (and later an arch-conservative), founded the Young Negroes Cooperative League (YNCL). It sought to develop black economic power through collective networks. They conducted "conferences and trainings in the 1930s in their attempt to create a small, interlocking system of cooperative economic societies throughout the US" for black economic development.[16] Having befriended Schuyler, Baker joined his group in 1931 and soon became its national director.[17][18]

Baker also worked for the Worker's Education Project of the Works Progress Administration, established under President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal. Baker taught courses in consumer education, labor history, and African history. She immersed herself in the cultural and political milieu of Harlem in the 1930s, protesting Italy's invasion of Ethiopia and supporting the campaign to free the Scottsboro defendants in Alabama. She also founded the Negro History Club at the Harlem Library and regularly attended lectures and meetings at the YWCA.[19]

During this time, Baker lived with and married her college sweetheart, T. J. (Bob) Roberts. They divorced in 1958. Baker rarely discussed her private life or marital status. According to fellow activist Bernice Johnson Reagon, many women in the Civil Rights Movement followed Baker's example, adopting a practice of dissemblance about their private lives that allowed them to be accepted as individuals in the movement.[20]

Baker befriended John Henrik Clarke, a future scholar and activist; Pauli Murray, a future writer and civil rights lawyer; and others who became lifelong friends.[21] The Harlem Renaissance influenced her thoughts and teachings. She advocated widespread, local action as a means of social change. Her emphasis on a grassroots approach to the struggle for equal rights influenced the growth and success of the civil rights movement of the mid-20th century.[22]

NAACP (1938–1953)

In 1938 Baker began her long association with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), then based in New York City. In December 1940 she started work there as a secretary. She traveled widely for the organization, especially in the South, recruiting members, raising money, and organizing local chapters. She was named director of branches in 1943,[23] and became the NAACP's highest-ranking woman. An outspoken woman, Baker believed in egalitarian ideals. She pushed the NAACP to decentralize its leadership structure and to aid its membership in more activist campaigns at the local level.[24]

Baker believed that the strength of an organization grew from the bottom up, not the top down. She believed that the branches' work was the NAACP's lifeblood. Baker despised elitism and placed her confidence in many. She believed that the bedrock of any social change organization is not its leaders' eloquence or credentials, but the commitment and hard work of the rank and file membership and their willingness and ability to engage in discussion, debate, and decision-making.[25] She especially stressed the importance of young people and women in the organization.[24]

While traveling throughout the South on the NAACP's behalf, Baker met hundreds of black people, establishing lasting relationships with them. She slept in their homes, ate at their tables, spoke in their churches, and earned their trust. She wrote thank-you notes and expressed her gratitude to the people she met. This personalized approach was one important aspect of Baker's effectiveness in recruiting more NAACP members.[26] She formed a network of people in the South who would be important in the continued fight for civil rights. Whereas some northern organizers tended to talk down to rural southerners, Baker's ability to treat everyone with respect helped her in recruiting. Baker fought to make the NAACP more democratic. She tried to find a balance between voicing her concerns and maintaining a unified front.[24]

Between 1944 and 1946, Baker directed leadership conferences in several major cities, such as Chicago and Atlanta. She got top officials to deliver lectures, offer welcoming remarks, and conduct workshops.[27]

In 1946, Baker took in her niece Jackie, whose mother was unable to care for her. Due to her new responsibilities, Baker left her full-time position with the NAACP and began to serve as a volunteer. She soon joined the NAACP's New York branch to work on local school desegregation and police brutality issues. She became its president in 1952.[28] In this role, she supervised the field secretaries and coordinated the national office's work with local groups.[23] Baker's top priority was to lessen the organization's bureaucracy and give women more power in the organization; this included reducing Walter Francis White's dominating role as executive secretary.[citation needed]

Baker believed the program should be primarily channeled not through White and the national office, but through the people in the field. She lobbied to reduce the rigid hierarchy, place more power in the hands of capable local leaders, and give local branches greater responsibility and autonomy.[29] In 1953 she resigned from the presidency to run for the New York City Council on the Liberal Party ticket, but was unsuccessful.[30]

Civil rights movement

| Part of a series on |

| Progressivism in the United States |

|---|

|

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (1957–1960)

In January 1957, Baker went to Atlanta to attend a conference aimed at developing a new regional organization to build on the success of the Montgomery bus boycott in Alabama. After a second conference in February, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was formed. This was planned as a loosely structured coalition of church-based leaders who were engaged in civil rights struggles across the South.[31] The group wanted to emphasize the use of nonviolent actions to bring about social progress and racial justice for southern blacks. They intended to rely on the existing black churches, at the heart of their communities, as a base of its support. Its strength would be built on the political activities of local church affiliates. The SCLC leaders envisioned themselves as the political arm of the black church.[32]

The SCLC first appeared publicly as an organization at the 1957 Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom. Baker was one of three major organizers of this large-scale event. She demonstrated her ability to straddle organizational lines, ignoring and minimizing rivalries and battles.[33] The conference's first project was the 1958 Crusade for Citizenship, a voter registration campaign to increase the number of registered African-American voters for the 1958 and 1960 elections. Baker was hired as associate director, the first staff person for the SCLC. Reverend John Tilley became the first executive director. Baker worked closely with southern civil rights activists in Georgia, Alabama, and Mississippi, and gained respect for her organizing abilities. She helped initiate voter registration campaigns and identify other local grievances. Their strategy included education, sermons in churches, and efforts to establish grassroots centers to stress the importance of the vote. They also planned to rely on the Civil Rights Act of 1957 to protect local voters.[34] While the project did not achieve its immediate goals, it laid the groundwork for strengthening local activist centers to build a mass movement for the vote across the South.[34] After John Tilley resigned as director of the SCLC, Baker lived and worked in Atlanta for two and a half years as interim executive director until Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker started in the role in April 1960.[35]

Baker's job with the SCLC was more frustrating than fruitful. She was unsettled politically, physically, and emotionally. She had no solid allies in the office.[22] Historian Thomas F. Jackson notes that Baker criticized the organization for "programmatic sluggishness and King's distance from the people. King was a better orator than democratic crusader[, she] concluded."[36]

Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (1960–1966)

That same year, 1960, on the heels of regional desegregation sit-ins led by black college students, Baker persuaded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to invite southern university students to the Southwide Youth Leadership Conference at Shaw University on Easter weekend. This was a gathering of sit-in leaders to meet, assess their struggles, and explore the possibilities for future actions.[37] At this meeting, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, pronounced "snick") was formed.[38]

Baker saw the potential for a special type of leadership by the young sit-in leaders, who were not yet prominent in the movement. She believed they could revitalize the Black Freedom Movement and take it in a new direction. Baker wanted to bring the sit-in participants together in a way that would sustain the momentum of their actions, teach them the skills necessary, provide the resources that were needed, and also help them to coalesce into a more militant and democratic force.[39] To this end she worked to keep the students independent of the older, church-based leadership. In her address at Shaw, she warned the activists to be wary of "leader-centered orientation". Julian Bond later described the speech as "an eye opener" and probably the best of the conference. "She didn't say, 'Don't let Martin Luther King tell you what to do,'" Bond remembers, "but you got the real feeling that that's what she meant."[40]

SNCC became the most active organization in the deeply oppressed Mississippi Delta. It was more open to women than the other prominent Civil Rights organizations, including the SCLC, where Baker witnessed extensive misogynistic teachings and the suppression of women activists. But widespread sexism and appeals to male supremacy pervaded its membership.[41] After the conference at Shaw, Baker resigned from the SCLC and began a long and close relationship with SNCC.[42] Along with Howard Zinn, she was one of SNCC's highly revered adult advisors, known as the "Godmother of SNCC".[43]

In 1961 Baker persuaded the SNCC to form two wings: one wing for direct action and the second wing for voter registration. With Baker's help SNCC, along with the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), coordinated the region-wide Freedom Rides of 1961. They also expanded their grassroots movement among black sharecroppers, tenant farmers, and others throughout the South. Ella Baker insisted that "strong people don't need strong leaders", and criticized the notion of a single charismatic leader of movements for social change. In keeping the idea of "participatory democracy", Baker wanted each person to get involved.[44] She also argued that "people under the heel", the most oppressed members of any community, "had to be the ones to decide what action they were going to take to get (out) from under their oppression".[45]

She was a teacher and mentor to the young people of SNCC, influencing such important future leaders as Julian Bond, Diane Nash, Stokely Carmichael, Curtis Muhammad, Bob Moses, and Bernice Johnson Reagon. Through SNCC, Baker's ideas of group-centered leadership and the need for radical democratic social change spread throughout the student movements of the 1960s. For instance, the Students for a Democratic Society, the major antiwar group of the day, promoted participatory democracy. These ideas also influenced a wide range of radical and progressive groups that would form in the 1960s and 1970s.[46]

In 1964 Baker helped organize the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP) as an alternative to the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party. She worked as the coordinator of the Washington office of the MFDP and accompanied a delegation of the MFDP to the 1964 National Democratic Party convention in Atlantic City, New Jersey. The group wanted to challenge the national party to affirm the rights of African Americans to participate in party elections in the South, where they were still largely disenfranchised. When MFDP delegates challenged the pro-segregationist, all-white official delegation, a major conflict ensued. The MFDP delegation was not seated, but their influence on the Democratic Party later helped to elect many black leaders in Mississippi. They forced a rule change to allow women and minorities to sit as delegates at the Democratic National Convention.[47]

The 1964 schism with the national Democratic Party led SNCC toward the "black power" position. Baker was less involved with SNCC during this period, but her withdrawal was due more to her declining health than to ideological differences. According to her biographer Barbara Ransby, Baker believed that black power was a relief from the "stale and unmoving demands and language of the more mainstream civil rights groups at the time."[48] She also accepted the turn towards armed self-defense that SNCC made in the course of its development. Her friend and biographer Joanne Grant wrote that "Baker, who always said that she would never be able to turn the other cheek, turned a blind eye to the prevalence of weapons. While she herself would rely on her fists ... she had no qualms about target practice."[49]

Later years

Southern Conference Education Fund (1962–1967)

From 1962 to 1967, Baker worked as the staff of the Southern Conference Education Fund (SCEF). Its goal was to help black and white people work together for social justice; the interracial desegregation and human rights group was based in the South.[22] SCEF raised funds for black activists, lobbied for implementation of President John F. Kennedy's civil rights proposals, and tried to educate southern whites about the evils of racism.[50] Federal civil rights legislation was passed by Congress and signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 and 1965, but implementation took years.

In SCEF, Baker worked closely with her friend Anne Braden, a white longtime anti-racist activist. Braden had been accused in the 1950s of being a communist by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC). Baker believed that socialism, the transitory phase toward communism, was a humane alternative to capitalism. She became a staunch defender of Braden and her husband Carl; she encouraged SNCC to reject red-baiting as divisive and unfair. During the 1960s, Baker participated in a speaking tour and co-hosted several meetings on the importance of linking civil rights and civil liberties.[51]

Final efforts (1968–1986)

In 1967 Baker returned to New York City, where she continued her activism. She later collaborated with Arthur Kinoy and others to form the Mass Party Organizing Committee, a socialist organization.[citation needed] In 1972 she traveled the country in support of the "Free Angela" campaign, demanding the release of activist and writer Angela Davis, who had been imprisoned on charges of kidnapping and murder in the Marin County Civic Center attacks.[citation needed] Davis was eventually acquitted.

Baker also supported the Puerto Rican independence movement and spoke out against apartheid in South Africa. She allied with a number of women's groups, including the Third World Women's Alliance and the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom. She remained an activist until her death on December 13, 1986, her 83rd birthday.[52]

Thought

In the 1960s, the idea of "participatory democracy" became popular among political activists, including those in the Civil Rights Movement. It took the traditional appeal of democracy and added direct citizen participation.[53]

The new movement had three primary emphases:

- An appeal for grassroots involvement of people throughout society, while making their own decisions

- The minimization of (bureaucratic) hierarchy and the associated emphasis on expertise and professionalism as a basis for leadership

- A call for direct action as an answer to fear, isolation, and intellectual detachment[54]

Baker said:

You didn't see me on television, you didn't see news stories about me. The kind of role that I tried to play was to pick up pieces or put together pieces out of which I hoped organization might come. My theory is, strong people don't need strong leaders.[55]

According to Mumia Abu-Jamal, Baker advocated a more collectivist model of leadership over the "prevailing messianic style of the period".[56] She was largely arguing against the structuring of the civil rights movement by the organization model of the black church. The black church then had largely female membership and male leadership. Baker questioned not only the gendered hierarchy of the civil rights movement but also that of the Black church.[56]

Baker, King, and other SCLC members were reported to have differences in opinion and philosophy during the 1950s and 1960s. She was older than many of the young ministers she worked with, which added to their tensions. She once said the "movement made Martin, and not Martin the movement". When she gave a speech urging activists to take control of the movement themselves, rather than rely on a leader with "heavy feet of clay", it was widely interpreted as a denunciation of King.[57]

Baker's philosophy was "power to the people".[19] If members worked together, she believed that a group's force could make significant changes.[19]

Legacy

Representation in media

- Portrayed by Audra McDonald in the 2023 film Rustin.[58]

- The 1981 documentary Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker, directed by Joanne Grant, explored Baker's important role in the civil rights movement.[59]

- Bernice Johnson Reagon wrote "Ella's Song", in Baker's honor, for Fundi.[60]

- Several biographies have been written of Baker, including Barbara Ransby's Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (2003),[61] published by the University of North Carolina Press.[62] Ransby is a historian and longtime activist.[63][64]

Honors

- In 1984, Baker received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women.[65]

- Her papers are held by the New York Public Library.[66]

- In 1994, Baker was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame.[67]

- In 1996, the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, a nonprofit strategy and action center based in Oakland, California, was founded and named for her.[68]

- The Ella Baker School in the Julia Richman Education Complex in New York City was founded in 1996.

- In 2003, The Ella Jo Baker Intentional Community Cooperative, a 15-unit co-housing community, began living together in a renovated house in Washington, DC.[69]

- Ella J. Baker House, a community center which supports at-risk youth in Dorchester, Boston, was created at some point before 2005.[70]

- In 2009, Baker was honored on a U.S. postage stamp.[71]

- In 2014, the University of California at Santa Barbara established a visiting professorship to honor Baker.[72]

- In 2021 the former Woodrow Wilson Montessori School in Houston was renamed the Baker Montessori School[73]

- In 2022, Minneapolis Public Schools changed the name of PreK-8 Jefferson Community School to Ella Baker Global Studies and Humanities Magnet School.[74]

- In 2025, a statue of Baker sculpted by artist Dana King was dedicated at Ohio State University Newark.[75]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b Robert, Pascal (February 21, 2013). "Ella Baker and the Limits of Charismatic Masculinity". Huffington Post.

- ^ "Tired of Giving In: Remembering Rosa Parks". Ella Baker Center. Archived from the original on July 15, 2019. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ 350.org; Hunter, Daniel (April 15, 2024). "Building Movement Capacity and Structure: Ella Baker and the Civil Rights Movement". The Commons Social Change Library. Retrieved February 5, 2025.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Ransby, Barbara (2003). Ella Baker & the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision. Chapel Hill, North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press. pp. 6. ISBN 978-0807856161.

- ^ Dastagir, Alia E. "The unsung heroes of the civil rights movement are black women you've never heard of". USA TODAY. Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Kealoha, Samantha (April 18, 2007). "Ella Baker (1903-1986)". Retrieved February 5, 2021.

- ^ Elliott, Aprele (1996). "Ella Baker: Free Agent in the Civil Rights Movement". Journal of Black Studies. 26 (5): 593–603. doi:10.1177/002193479602600505. ISSN 0021-9347. JSTOR 2784885. S2CID 144321434.

- ^ James, Joy (1994). "Ella Baker, 'Black Women's Work' and Activist Intellectuals". The Black Scholar. 24 (4): 8–15. doi:10.1080/00064246.1994.11413167. ISSN 0006-4246. JSTOR 41069719.

- ^ a b Randolph, Irv (March 2, 2019). "Randolph: The work and wisdom of Ella Baker". The Philadelphia Tribune. Retrieved December 7, 2019.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 14.

- ^ a b Ransby (2003), pp. 29–31.

- ^ a b Davis, Marcia. "Ella Baker: An Unsung Civil Rights-Era Legend." The Crisis, vol. 110, no. 3, May 2003, pp. 48–49. ProQuest 199627266

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 13–63.

- ^ "Ella Baker's Story". Ella Baker Women's Center. Archived from the original on June 14, 2020. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- ^ "Who Was Ella Baker?". Ella Baker Center. Retrieved June 5, 2019.

- ^ Nembhard, Jessica Gordon (October 21, 2015). "The Black Co-op Movement: The Silent Partner in Critical Moments of African-American History". The Daily Kos (Interview). Interviewed by Beverly Bell; Natalie Miller.

- ^ Johnson, Cedric Kwesi (September 8, 2003). "A Woman of Influence". In These Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2008. Retrieved February 18, 2008.

- ^ Ransby, Barbara (1994). "Ella Josephine Baker". In Buhle, Mary Jo; et al. (eds.). The American Radical. London: Psychology Press. p. 290. ISBN 9780415908047.

- ^ a b c Elliott, Aprele (May 1996). "Ella Baker: Free Agent in the Civil Rights Movement". Journal of Black Studies. 26 (5). Newbury Park, California: Sage Publishing: 593–603. doi:10.1177/002193479602600505. JSTOR 2784885. S2CID 144321434.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 9.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 64–104.

- ^ a b c Ransby, Ella Baker (2003).

- ^ a b Ransby (2003), p. 137.

- ^ a b c "Ella Baker: Backbone of the Civil Rights Movement | The Jackson Advocate". Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved January 22, 2021.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 139.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 136.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 150.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 148.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 138.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 105–158.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 174.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 175.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 176.

- ^ a b Morris, Aldon D. (1986). The Origins of the Civil Rights Movement. New York City: Simon and Schuster. pp. 102–108. ISBN 9780029221303.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 170–175.

- ^ Jackson, Thomas F. (2007). From Civil Rights to Human Rights: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Struggle for Economic Justice. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 104. ISBN 978-0812220896.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 240.

- ^ Equal Justic Initiative. "April 15 - Birth of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC)". A History of Racial Justice. Archived from the original on August 9, 2020.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 239.

- ^ o'Malley, Susan Gushee (2000). Baker, Ella Josephine (13 December 1903–13 December 1986), civil rights organizer | American National Biography. doi:10.1093/anb/9780198606697.article.1500989. ISBN 978-0-19-860669-7. Retrieved May 10, 2019.

{{cite book}}:|website=ignored (help) - ^ Women in the Civil Rights Movement, p. 2.

- ^ Creating Black Americans, p. 291.

- ^ DEGREGORY, CRYSTAL (April 17, 2012). "Godmother of SNCC: Remembering Shaw Alumna Ella Baker". hbcustory. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Creating Black Americans, p. 292.

- ^ Boyte, Harry (July 1, 2015). "Ella Baker and the Politics of Hope -- Lessons From the Civil Rights Movement". HuffPost. Retrieved June 3, 2019.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 239–272.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 330–344.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 347–351.

- ^ Grant, Joanne, Ella Baker: Freedom Bound (Wiley, 1999), pp. 194–199.

- ^ Ransby (2003), p. 231.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 209–238, 273–328.

- ^ Ransby (2003), pp. 344–374.

- ^ Dictionary.com. "Participatory democracy". www.dictionary.com. Archived from the original on March 24, 2016. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ Women in the Civil Rights Movement, pp. 51–52.

- ^ Women in the Civil Rights Movement, p. 51.

- ^ a b Abu-Jamal, Mumia. We Want Freedom: A Life in the Black Panther Party. South End Press: Cambridge, 2004. p. 159.

- ^ Barbra Harris, "Ella Baker: Backbone of the Civil Rights Movement" Archived August 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, Jackson Advocate News Service

- ^ Lang, Brent (October 5, 2021). "Colman Domingo, Chris Rock, Audra McDonald Starring in 'Rustin' for Obamas' Higher Ground". Variety. Retrieved November 19, 2023.

- ^ "Click - Women in Civil Rights - Women in the Civil Rights Movement, Ella Baker, Black Women and Civil Rights, Women and Civil Rights Act". www.cliohistory.org. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Joy of Resistance proudly presents Fundi--The Story of Ella Baker", WBAI.org, May 28, 2014.

- ^ Ransby, Barbara (2003). Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-2778-9.

- ^ Hill, Copyright 2016 The University of North Carolina at Chapel. "UNC Press - Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement". uncpress.unc.edu. Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Ransby, Barbara (June 12, 2015). "Ella Taught Me: Shattering the Myth of the Leaderless Movement". ColorLines.

- ^ Ransby, Barbara (April 4, 2011). "Quilting a Movement". In These Times. ISSN 0160-5992. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ^ "Candace Award Recipients 1982-1990, Page 1". National Coalition of 100 Black Women. Archived from the original on March 14, 2003.

- ^ Ella Baker papers, 1926-1986, New York Public Library

- ^ "Baker, Ella". National Women’s Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ "Who Was Ella Baker?". Ella Baker Center for Human Rights. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Ella Jo Baker Intentional Community Cooperative, Inc". Foundation for Intentional Community. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Boston Foundation grants mean more summer jobs for teens". TBF. Retrieved December 12, 2020.

- ^ "Civil Rights Pioneers Honored on Stamps". about.usps.com. Retrieved January 23, 2021.

- ^ "Shana Redmonds Named to Professorship Honoring Civil Rights Activist Ella Baker". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education. October 20, 2014. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- ^ Carpenter, Jacob (April 8, 2021). "Houston ISD board approves Wilson Montessori name change, citing former president's racist actions". Houston Chronicle. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Rybak, Charlie (January 31, 2022). "Jefferson Students Vote to Name School after American Hero Ella Baker". Southwest Voices. Retrieved August 22, 2024.

- ^ "Civil Rights activist statue unveiled at Ohio State University Newark". WCMH. October 17, 2025. Retrieved December 24, 2025.

References

- S. G. O'Malley, "Baker, Ella Josephine", American National Biography Online (2000).

- G. J. Barker Benfield and Catherine Clinton, eds., Portraits of American Women (1991).

- Ellen Cantarow and Susan O'Malley, Moving the Mountain: Women Working for Social Change (1980).

- Joanne Grant, Ella Baker: Freedom Bound (John Wiley & Sons, 1998).

- Barbara Ransby, Ella Baker and the Black Freedom Movement: A Radical Democratic Vision (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2003), ISBN 0-8078-2778-9

- Henry Louis Gates and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, African American Lives(2004), ISBN 0-19-516024-X

Further reading

- Inouye, M. (2021). "Starting with People Where They Are: Ella Baker’s Theory of Political Organizing". American Political Science Review

- Moye, J. Todd (2013). Ella Baker: Community Organizer of the Civil Rights Movement. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9781442215665.

External links

- SNCC Digital Gateway: Ella Baker, Documentary website created by the SNCC Legacy Project and Duke University, telling the story of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee & grassroots organizing from the inside-out

- Biography: Ella Baker, SNCC-People, iBiblio

- The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights

- Ella J. Baker Biography, NC State University's College of Humanities and Social Sciences

- Oral History Interviews with Ella Baker [1], [2] at Oral Histories of the American South, Documenting the American South

- "Ella Baker - Freedom Bound" by Joanne Grant

- Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker, a film by Joanne Grant

- Video clip of Fundi: The Story of Ella Baker, Click! The Ongoing Feminist Revolution

- "Ella Baker," One Person, One Vote Archived July 16, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, SNCC