The African slave trade was first brought to Alabama when the region was part of the French Louisiana Colony.[1]

The African slave trade was first brought to Alabama when the region was part of the French Louisiana Colony.[1]

During the colonial era, Indian slavery in Alabama soon became surpassed by industrial-scale plantation slavery in large part due to the rapid growth of the cotton industry.[2][3]

Settlement and cotton industry expansion

Originally part of the Mississippi Territory, the Alabama Territory was formed in 1817. Like its neighbors, the Alabama Territory was fertile ground for the surging cotton crop, and soon became one of the major destinations for African-American slaves who were being shipped to the Southeastern United States. Following the patenting of the cotton gin (in 1793), the War of 1812, and the defeat and expulsion of the Creek Nation in the 1810s, European-American settlement in Alabama was intensified, as was the presence of slavery on newly established plantations in the territory. Minister Elias Cornelius observed slave trading in Huntsville in 1817, writing in his journal:[4]

"The people seemed to me to almost infatuate with the prospect of making money. There is however a serious subtraction to be made from their prosperity—sickness and vice find in this region a most congenial & luxuriant soil Slaves are in great demand & will probably ere long constitute the principal part of the population of the country. The high demand for slaves made by the cotton planters holds out a most powerful inducement encouragement to the prosecution of that great abominable traffic in human flesh in the southern country are engaged in. The miserable objects of this traffic are brought up in the old states and driven like cattle to the western market when they are sold & bought with as little computation [?] of conscience as if they were so many hogs or sheep. One of these sales I witnessed myself at Huntsville, during the short stay I made there—a number of Africans were taken to the center of the public square & soon a crowd of spectators & purchasers assembled."[4]

Alabama was admitted as the 22nd state on December 14, 1819. Huntsville, Alabama, served as temporary capital from 1819 to 1820, when the seat of government moved to Cahaba in Dallas County.[5][6] Within 20 years of becoming a state, Alabama was the largest cotton producer in the US, producing 23% of the nation's cotton crop.[7][8]

The Alabama Fever land rush was underway when the state was admitted to the Union, with settlers and land speculators pouring into the state to take advantage of fertile land suitable for cotton cultivation.[9][10] Part of the frontier in the 1820s and 1830s, its constitution provided for universal suffrage for white men.[11]

Alabama had an estimated population of under 10,000 people in 1810, but it increased to more than 300,000 people by 1830.[9] Most Native American tribes were completely removed from the state within a few years of the passage of the Indian Removal Act by Congress in 1830.[12][13]

By 1861 nearly 45% of the population of Alabama were slaves, and slave plantation agriculture was the center of the Alabama economy.[14][11] Cotton made up over half of US exports at the time, and southern plantations produced three-fourths of the global cotton supply.[15]

Civil war and abolition

Alabama was one of the first seven states to withdraw from the Union prior to the American Civil War.

The slave trade continued unabated in Alabama until at least 1863, with busy markets in Mobile and Montgomery largely undisputed by the war.[16]: 99–100

Slavery had been theoretically abolished by President Abraham Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation which proclaimed, in 1863, that only slaves located in territories that were in rebellion from the United States were free. Since the U.S. government was not in effective control of many of these territories until later in the war, many of these slaves proclaimed to be free by the Emancipation Proclamation were still held in servitude until those areas came back under Union control. Chattel slavery was officially abolished in the United States, following the end of the American Civil War by the Thirteenth Amendment which took effect on December 18, 1865.

Reconstruction and the Jim Crow era

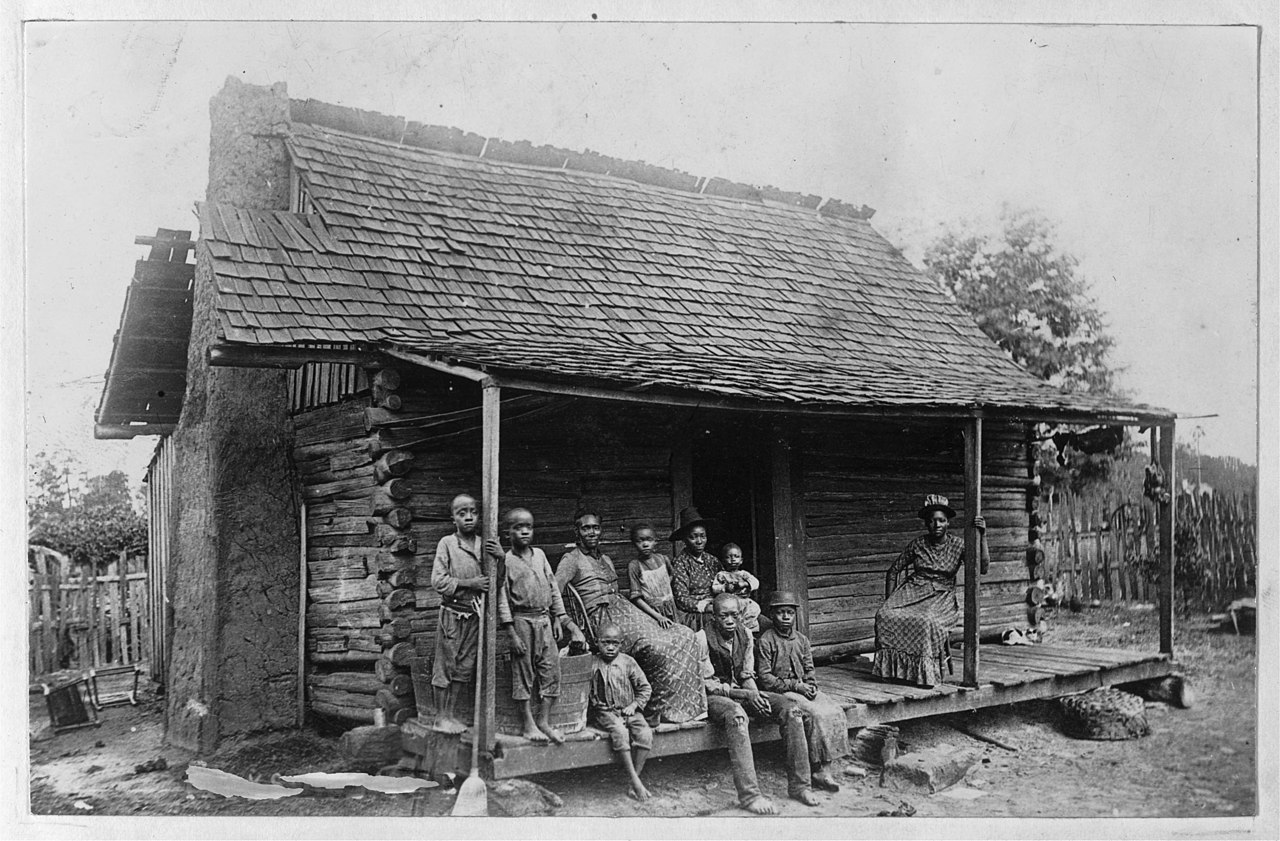

Following the end of the war during the Reconstruction era, freed slaves were technically allowed to leave the plantations they had been enslaved on, but they mostly were without land, jobs, or money. Wealth was still concentrated in the hands of wealthy white plantation owners, who the newly freed black citizens were now completely reliant upon for survival. Contract labor systems were put into place in southern states that forced freed blacks to work in jobs that they could not legally quit, left them permanently in debt, and which often involved violent physical punishment by white property owners. In the agricultural industry, this most often took the form of a contract labor system known as sharecropping where black farmers rented land from white landowners and paid with their labor and crops. Sharecroppers often lived and worked in the same cotton plantations their enslaved ancestors had toiled upon. Many black laborers refused to continue working the plantations, and chose to migrate to southern urban areas in large numbers.[14][17]

See also

- List of plantations in Alabama

- Plantation complexes in the Southern United States

- History of slavery in the United States by state

- List of Alabama slave traders

References

- ^ Sellers, James Benson (1994). Slavery in Alabama. University of Alabama Press. p. 3. ISBN 9780817305949.

- ^ Ethridge, Robbie Franklyn, and Sheri Marie Shuck-Hall. 2009. Mapping the Mississippian Shatter Zone: The Colonial Indian Slave Trade and Regional Instability in the American South. University of Nebraska Press

- ^ Baine, Rodney M. 1995. "Indian Slavery in Colonial Georgia." The Georgia Historical Quarterly 79 (2).

- ^ a b Davis, Robert S. (2019) "Three Visits to Huntsville Before the Civil War,"Huntsville Historical Review: Vol. 44: No. 2, Article 6. https://louis.uah.edu/huntsville-historical-review/vol44/iss2/6

- ^ "Huntsville". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. Alabama Humanities Foundation. Archived from the original on January 22, 2013. Retrieved January 22, 2013.

- ^ "Old Cahawba, Alabama's first state capital, 1820 to 1826". Old Cahawba: A Cahawba Advisory Committee Project. Archived from the original on August 21, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ Hilton, Mark. "Cotton State / Slavery". Historical Marker Database.

- ^ Bunn, Mike. "Alabama Territory: Spring 1818". Alabama Heritage. University of Alabama. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ a b LeeAnna Keith (October 13, 2011). "Alabama Fever". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ "Alabama Fever". Alabama Department of Archives and History. State of Alabama. Archived from the original on January 17, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Tullos, Allen (April 19, 2004). "The Black Belt". Southern Spaces. Emory University. doi:10.18737/M70K6P. Archived from the original on January 11, 2011. Retrieved September 23, 2006.

- ^ AL.com, al com | (2019-12-28). "Alabama's population: 1800 to the modern era". al. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ Wayne Flynt (July 9, 2008). "Alabama". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved September 22, 2012.

- ^ a b Martin, David (1993). "The Birth of Jim Crow in Alabama 1865-1896" (PDF). National Black Law Journal. 13 (1): 184–197.

- ^ "The Cotton Kingdom Era". Alabama Black Belt Heritage Area.

- ^ Colby, Robert K.D. (2024-05-18), ""Old Abe Is Not Feared in This Region": The Revival of Confederate Slave Commerce", An Unholy Traffic (1 ed.), Oxford University PressNew York, pp. 78–107, doi:10.1093/oso/9780197578261.003.0004, ISBN 978-0-19-757826-1, retrieved 2024-03-23

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: work parameter with ISBN (link)

Further reading

- Hebert, Keith S. (2009). "Slavery". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Alabama Humanities Foundation.

- Williams, Horace Randall, ed. (2004). Weren't No Good Times: Personal Accounts of Slavery in Alabama. Winston-Salem, N.C.: John F. Blair. ISBN 9780895872845.

- Meier, August; Rudwick, Elliot M. (1966). From Plantation to Ghetto. New York: Hill & Wang.

- Thornton, J. Mills (1978). Politics and Power in a Slave Society: Alabama, 1800-1860. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press.

- Sellers, James Benson (1994). Slavery in Alabama. First published in 1964 (2nd ed.). Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0817305947.

- Davis, Charles S. (1974). The cotton kingdom in Alabama. First published in 1939. Philadelphia: Porcupine Press. OCLC 0879913298.

- Burton, Annie L. (1909). Memories of Childhood's Slavery Days. Boston: Ross Publishing Company.

External links

- The Alabama Supreme Court on Slaves

- Alabama Department of Archives and History

- "Slavery" Keith S. Hebert, Encyclopedia of Alabama (Auburn University)