Homo naledi is an extinct species of archaic human discovered in 2013 in the Rising Star Cave, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa dating to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specimens, representing 737 different elements, and at least 15 different individuals. Despite this exceptionally high number of specimens, their classification with other Homo species remains unclear.

| Homo naledi Temporal range: Middle Pleistocene

| |

|---|---|

| |

| The 737 known elements of H. naledi | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Suborder: | Haplorhini |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. naledi

|

| Binomial name | |

| †Homo naledi Berger et al., 2015

| |

| |

| Location of Rising Star Cave in Cradle of Humankind, South Africa. | |

Homo naledi is an extinct species of archaic human discovered in 2013 in the Rising Star Cave system, Gauteng province, South Africa, part of the Cradle of Humankind, dating back to the Middle Pleistocene 335,000–236,000 years ago. The initial discovery comprises 1,550 specimens of bone, representing 737 different skeletal elements, and at least 15 different individuals. Despite this exceptionally high number of specimens, their classification with other Homo species remains unclear.

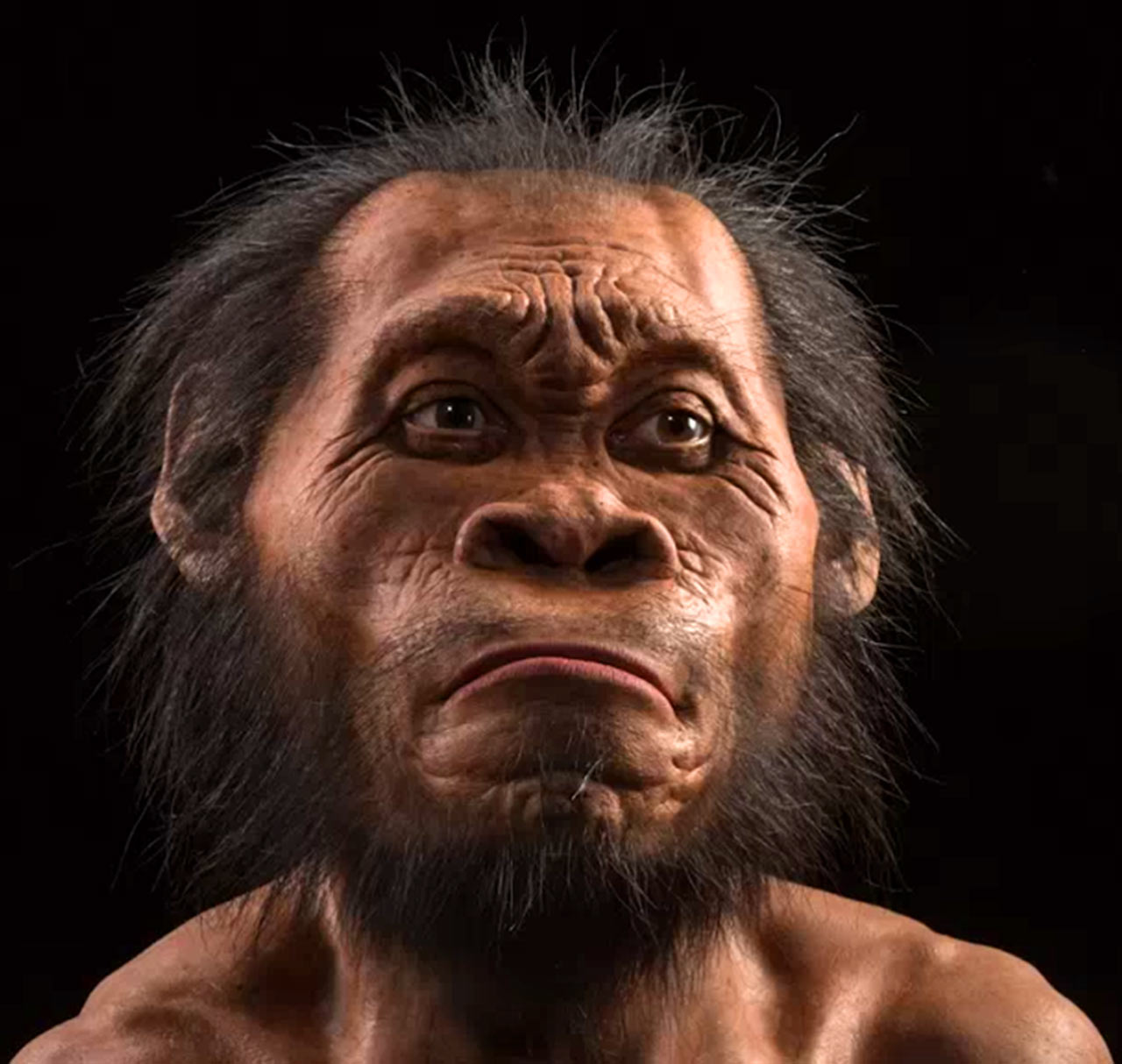

Along with similarities to contemporary Homo, they share several characteristics with the ancestral Australopithecus as well as early Homo (mosaic evolution), most notably a small cranial capacity of 465–610 cm3 (28.4–37.2 cu in), compared with 1,270–1,330 cm3 (78–81 cu in) in modern humans. They are estimated to have averaged 143.6 cm (4 ft 9 in) in height and 39.7 kg (88 lb) in weight, yielding a small relative brain size, encephalization quotient, of 4.5. H. naledi brain anatomy seems to have been similar to contemporary Homo, which could indicate comparable cognitive complexity. The persistence of small-brained humans for so long in the midst of bigger-brained contemporaries revises the previous conception that a larger brain would necessarily lead to an evolutionary advantage, and their mosaic anatomy greatly expands the known range of variation for the genus.

H. naledi anatomy indicates that, although they were capable of long-distance travel with a humanlike stride and gait, they were more arboreal than other Homo, better adapted to climbing and suspensory behaviour in trees than endurance running. Tooth anatomy suggests consumption of gritty foods covered in particulates such as dust or dirt, suggesting a diet of nuts and tubers.[2]

Although they have not been associated with stone tools or any indication of material culture, they appear to have been dexterous enough to produce and handle tools, and therefore may have manufactured Early or Middle Stone Age industries found in excavations near their fossils, since no other human species in the vicinity at that time has been discovered. It has also been controversially postulated that these individuals were buried deliberately by being carried into and placed in the chamber. Some researchers suggest that H. naledi also may have carved crosshatched rock signs in a passage to what could be a burial chamber, but many paleontologists question this hypothesis.

Discovery

On 13 September 2013 while exploring the Rising Star Cave system in the Cradle of Humankind, South Africa, cavers Rick Hunter and Steven Tucker found hominin fossils at the bottom of the Dinaledi Chamber.[3] On 24 September, they returned to the chamber and took photographs that they showed to South African palaeoanthropologists Pedro Boshoff and Lee Rogers Berger on 1 October.[3] Berger assembled an excavation team that included Hunter and Tucker, the so-called "Underground Astronauts".[4]

The chamber had been entered at least once before, by cavers in the early 1990s. They rearranged some bones and may have caused further damage, although much of the floor in the chamber had not been walked on prior to 2013.[5] The site lies about 80 m (260 ft) from the main entrance, at the bottom of a 12 m (39 ft) vertical drop, and the 10 m (33 ft) long main passage is only 25–50 cm (10 in – 1 ft 8 in) at its narrowest.[5] In total, more than 1,550 pieces of bone belonging to at least fifteen individuals (9 immature and 6 adults)[6] have been recovered from the clay-rich sediments. Berger and colleagues published the findings in 2015.[7]

The fossils represent 737 anatomical elements – including portions of the skull, jaw, ribs, teeth, limbs, and inner ear bones – from old, adult, young, and infantile individuals. There are also some articulated or near-articulated elements, including the skull with the jaw bone, and nearly complete hands and feet.[7][5] With the number of individuals of both genders across several age demographics, it then became the richest assemblage of associated fossil hominins discovered in Africa. Aside from the Sima de los Huesos collection and later Neanderthal and modern human samples, the excavation site has the most comprehensive representation of skeletal elements across the lifespan, and from multiple individuals, in the hominin fossil record by that time.[7]

The holotype specimen, DH1, comprises a male partial calvaria (top of the skull), partial maxilla, and nearly complete jawbone. The paratypes, DH2 through DH5, all comprise partial calvaria. Because the remains came from Rising Star Cave, in 2015, Berger and colleagues named the species Homo naledi with the specific name meaning "star" in the Sotho language.[7]

The remains of at least three additional individuals (two adults and a child) were reported in the Lesedi Chamber of the cave by John Hawks and colleagues in 2017.[8]

Classification

In 2017, the Dinaledi remains were dated to 335,000–236,000 years ago in the Middle Pleistocene, using electron spin resonance (ESR) and uranium–thorium (U-Th) dating on three teeth, and U-Th and paleomagnetic dating of the sediments they were deposited in.[1] Previously, the fossils were thought to have dated to 1–2 million years ago,[7][9][10][4] because no similarly small-brained hominins had been known from such a recent date in Africa.[11] The smaller-brained Homo floresiensis of Indonesia lived on an isolated island and, apparently, became extinct shortly after the arrival of modern humans.[12]

The ability of such a small-brained hominin to have survived for so long in the midst of bigger-brained Homo has greatly revised previous conceptions of human evolution and the notion that a larger brain would necessarily lead to an evolutionary advantage.[11] Their mosaic anatomy also greatly expands the range of variation for the genus.[13]

H. naledi is hypothesised to have branched off very early from contemporaneous Homo. It is unclear whether they branched off at approximately the time of H. habilis, H. rudolfensis, and A. sediba, are a sister taxon to H. erectus and the contemporaneous large-brained Homo, or are a sister taxon to the descendants of H. heidelbergensis (modern humans and Neanderthals). This places the branching from contemporary Homo in a range of time from as early as the Pliocene to 900,000 years ago at the latest. It is also possible that their ancestors speciated after an interbreeding event between Homo and late australopithecines.[11] Comparison of skull features reveals that H. naledi has the closest affinities to H. erectus.[13]

It is unclear whether these H. naledi were an isolated population in the Cradle of Humankind, or were ranged across Africa. If the latter, then several gracile hominin fossils from African sites that traditionally have been classified as late H. erectus might instead represent H. naledi specimens.[14]

Although earlier study placed H. naledi as a late offshoot from H. erectus in the phylogenetic tree,[15] the recent study places H. naledi as an early offshoot from H. erectus in the phylogenetic tree.[16]

Anatomy

Skull

Two male H. naledi skulls from the Dinaledi chamber had cranial volumes of approximately 560 cm3 (34 cu in), and two female skulls 465 cm3 (28.4 cu in). A male H. naledi skull from the Lesedi chamber had a cranial volume of 610 cm3 (37 cu in). The Dinaledi specimens are more similar to the cranial capacity of australopithecines. For comparison, H. erectus averaged approximately 900 cm3 (55 cu in),[8] and modern humans 1,270 and 1,130 cm3 (78 and 69 cu in) for males and females respectively.[17] The Lesedi specimen is more within the range of H. habilis and H. e. georgicus. The encephalization quotient of H. naledi was estimated at 3.75, which is the same as the pygmy H. floresiensis, but notably smaller than all other Homo. Contemporary Homo were all above 6, H. e. georgicus at 3.55, and A. africanus at 3.81.[18] It is unclear whether H. naledi inherited small brain size from the last common Homo ancestor, or whether it was evolved secondarily and more recently.[19]

The skull morphology is more similar to Homo, with a slenderer shape, the asymmetry in both the temporal and occipital lobes of the brain, and reduced post-orbital constriction, with the skull not becoming narrower behind the eye-sockets.[7][19] The frontal lobe morphology is more or less the same in all Homo brains despite size, and differs from Australopithecus, a characteristic that has been implicated in the production of tools, the development of language, and sociality.[19]

Similarly to modern humans (but not to fossil hominins, including South African australopithecines, H. erectus, and Neanderthals) the permanent second molar of H. naledi erupted comparatively late in life, emerging alongside the premolars instead of before, a characteristic that indicates a slower maturation unusually comparable to modern humans.[20] The tooth formation rate of the front teeth is also most similar to modern humans.[21] The overall size and shape of the molars most closely resemble those of three unidentified Homo specimens from the local Swartkrans and East African Koobi Fora Caves, and are similar in size (but not shape) to Pleistocene H. sapiens. The necks of the molars are proportionally similar to those of A. afarensis and Paranthropus.[22]

Unlike modern humans and contemporary Homo, H. naledi lacks several accessory dental features, and has a high frequency of individuals who present main cusps, namely the metacone (midline on the tongue-side) and hypocone (to the right on the lip-side) on the second and third molars, and a Y-shaped hypoconulid (a ridge on the lip-side toward the cheek) on all three molars.[23] The premolars of H. naledi are characterised by a well-developed P3 and P4 metaconid, strongly developed P3 mesial marginal ridge, a larger P3 than P4, and tall crowns, distinguishing them from the premolars of other Homo species.[24] Nonetheless, H. naledi also has many dental similarities with contemporary Homo.[23]

The anvil (a middle ear bone) more resembles those of chimps, gorillas, and Paranthropus than Homo.[25] Like H. habilis and H. erectus, H. naledi has a well-developed brow-ridge with a fissure stretching across just above the ridge and, like H. erectus, a pronounced occipital bun. H. naledi has some facial similarities with H. rudolfensis.[23]

Build

The H. naledi specimens are estimated to have, on average, stood approximately 143.6 cm (4 ft 9 in) and weighed 39.7 kg (88 lb). This body mass is intermediate between what is typically seen in Australopithecus and Homo species. Like other Homo, female and male H. naledi were likely about the same size, males on average about 20% larger than females.[18] A juvenile specimen, DH7, is skeletally consistent with a growth rate similar to the faster ape-like trajectories of MH1 (A. sediba) and Turkana boy (H. ergaster). Because dental development is so similar to that of modern humans, a slower maturation rate is not completely out of the question. Using the faster growth rate, DH7 would have died at 8–11 years old, but using the slower growth, DH7 would have died at 11–15 years old.[26]

Concerning the spine, only the tenth and eleventh thoracic vertebrae (in the chest region) are preserved from presumably a single individual, which are proportionally similar to those of contemporary Homo, although being the smallest recorded of any hominin. The two transverse processes of the vertebra, which jut out diagonally, are most similar to those of Neanderthals. The neural canals within are proportionally large, similar to modern humans, Neanderthals, and H. e. georgicus. The eleventh rib is straight like that of A. afarensis, and the twelfth rib is robust in cross-section like that of Neanderthals. Like Neanderthals, the twelfth rib appears to have supported strong intercostal muscles above, and a strong quadratus lumborum muscle below. Unlike Neanderthals, there was weak attachment to the diaphragm. Overall, this H. naledi specimen appears to have been small-bodied compared with other Homo species, although it is unclear whether this single specimen is representative of the species.[27]

The shoulders are more similar to those of australopithecines, with the shoulder blade situated higher on the back and farther from the midline, short clavicles, and little or no humeral torsion.[7] Elevated shoulder and clavicle bones indicate a narrow chest.[27] The pelvis and legs have features reminiscent of Australopithecus, including anterposteriorly compressed (from front to back) femoral necks, mediolaterally compressed (from left to right) tibiae, and a somewhat circular fibular neck;[28][29] which indicate a wide abdomen. This combination would preclude efficient endurance running in H. naledi, unlike H. erectus and descendants. Instead, H. naledi appears to have been more arboreal.[27]

Limbs

The metacarpal bone of the thumb, which is used in holding and manipulating large objects, was well-developed and had strong crests to support its opponens pollicis muscle used in precision-pinch gripping, and its thenar muscles. This is more similar to other Homo than Australopithecus. H. naledi appears to have had strong flexor pollicis longus muscles like modern humans, with humanlike palm and finger pads, which are important for forceful gripping between the thumb and fingers. Unlike Homo, the H. naledi thumb metacarpal joint is comparably small, relative to the thumb's length, and the thumb phalangeal joint is flattened. The distal thumb phalanx bone is robust, and proportionally more similar to those of H. habilis and P. robustus.[30]

The metacarpals of the other fingers share adaptations with modern humans and Neanderthals to be able to cup and manipulate objects, and the wrist joint is broadly similar to that of modern humans and Neanderthals. Conversely, the proximal phalanges are curved and are almost identical to those of A. afarensis and H. habilis, which is interpreted as an adaptation for climbing and suspensory behaviour. Such curvature is more pronounced in adults than juveniles, suggesting that adults climbed just as much or more so than juveniles, and this behaviour was common. The fingers are proportionally longer than those of any other fossil hominin, other than the arboreal Ardipithecus ramidus and a modern human specimen from Qafzeh cave, Israel, which is consistent with climbing behaviour.[30]

H. naledi was a biped and stood upright.[7] Like other Homo, they had strong insertion for the gluteus muscles, well-defined linea aspera (a ridge running down the back of the femur), thick patellae, long tibiae, and gracile fibulae. These indicate that they were capable of long-distance travel.[29] The H. naledi foot was similar to that of modern humans and other Homo, with adaptations for bipedalism and a humanlike gait. The heel bone has a low orientation, comparable to those of non-human great apes, and the ankle bone has a low declination, which possibly indicate the foot would have been subtly stiffer during the stance phase of walking before the foot pushed off the ground.[31]

Pathology

The adult right mandible U.W. 101-1142 has a bony lesion, suggestive of a benign tumour. The individual would have experienced some swelling and localised discomfort, but the tumour's position near the medial pterygoid muscle (likely causing discomfort on the jaw hinge) may have impeded function of the muscle, and changed elevation of the right side of the jaw.[32]

Dental defects in H. naledi specimens during 1.6–2.8 and 4.3–7.6 months of development were most likely caused by seasonal stressors. This may have been due to extreme summer and winter temperatures causing food scarcity. Minimum winter temperatures of the area average about 3 °C (37 °F), and can drop below freezing. Staying warm for an infant of the small-bodied H. naledi would have been difficult, and winters likely increased susceptibility to respiratory diseases. Environmental stressors are consistent with present-day flu seasons in South Africa peaking during winter, and paediatric diarrhoea hospitalisation being most frequent at the height of the rainy season in summer.[33]

Local hominins were likely preyed upon by large carnivores, such as lions, leopards, and hyaenas. There seems to be a distinct paucity of large carnivore remains from the northern end of the Cradle of Humankind, where Rising Star Cave is located, possibly because carnivores preferred the Blaaubank River to the south that may have offered better hunting grounds with a greater abundance of large prey items. Alternatively, because many more sites are known in the south than the north, carnivore spatial patterns may not be well-represented by the fossil record (preservation bias).[34]

Culture

Food

Dental chipping and wearing indicates the habitual consumption of small hard objects, such as dirt and dust, and cup-shaped wearing on the back teeth may have stemmed from gritty particles. These could have originated from unwashed roots and tubers. Alternatively, aridity could have stirred up particulates onto food items, coating food in dust. It is possible that they commonly ate larger hard items, such as seeds and nuts, but these were processed into smaller pieces before consumption.[35][36]

H. naledi occupied a seemingly unique ecological niche from previous South African hominins, including Australopithecus and Paranthropus. The teeth of all three species indicate that they needed to exert high shearing force to chew through perhaps plant or muscle fibres. The teeth of other Homo cannot produce such high forces perhaps due to the use of some food processing techniques, such as cooking.[35]

Technology

H. naledi could have produced Early Stone Age (Acheulean and possibly the earlier Oldowan) or Middle Stone Age industries because they have the same adaptations to the hand as other human species that are implicated in tool production.[11][18] H. naledi is the only identified human species to have existed during the early Middle Stone Age of the Highveld region, South Africa, possibly indicating that this species manufactured and maintained this tradition at least during this time period. In this scenario, such industries and stone cutting techniques would have evolved independently several times among different Homo species and populations, or were transported over long distances by the inventors or apprentices and taught.[11]

Possible burials

Since the first publication of results from the Dinaledi Chamber, there has been scholarly debate on whether the fossils excavated from the cave provide evidence of H. naledi engaging in intentional burial activity. If proven true, Dinaledi Chamber would be the oldest known hominin burial, beating out the c. 78,000 year old H. sapiens burial from Panga ya Saidi cave in Kenya by some 160,000 years.[37][38][39] However, a lack of proof regarding the taphonomic, stratigraphic, and mineralogical claims made by the excavators has caused significant academic backlash.

In 2015, excavating archaeologists Paul Dirks, Lee Berger, and their colleagues concluded that the bodies had to have been deliberately carried and placed into the chamber by people because they appear to have been intact when they were first deposited in the chamber. They found no evidence of trauma from being dropped into the chamber nor evidence of predation. Furthermore, the chamber is inaccessible to large predators, appears to be an isolated system, and has never been flooded. There is no hidden shaft through which people could have accidentally fallen in, and there is no evidence of some catastrophe that killed all the individuals inside the chamber. The excavating team stated that it is possible that the bodies were dropped down a chute and fell slowly due to the narrowness and irregularity of the path down. Thus, they concluded that, since natural forces were apparently not at play, the bodies must have been deliberately buried. Since the cave is unlit, those burying them would have required artificial light to navigate the cave. The archaeologists have reported finding evidence for fire which may support this claim, yet they have not published it as of July 2024.[40] The excavators claim that the site was used repeatedly for burials since the bodies were not all deposited at the same time.[41]

In 2016, paleoanthropologist Aurore Val countered that discounting natural forces for depositing the bodies is unjustified. She identified evidence of damage done by beetles, beetle larvae, and snails, which facilitate decomposition. Since the chamber does not present ideal conditions for snails and does not contain snail shells, she argued that decomposition began before deposition in the chamber, potentially discounting the excavators' claims of intentional burial.[42] Invertebrate damage to the fossils was later confirmed by a 2021 analysis of a fragmentary skull, although this analysis also concludes that it is likely that "some" hominin agency was involved in the deposition of the bone fragments.[43]

In 2017, Dirks, Berger, and colleagues reaffirmed that there is no evidence of water flow into the cave and that it is more likely that the bodies were deliberately deposited into the chamber. They theorized that as it is possible that the H. naledi bones were deposited by contemporary Homo, such as the ancestors of modern humans, rather than other H. naledi, but that the cultural behavior of burial practices is not impossible for H. naledi. They proposed that placement in the chamber may have been done to remove decaying bodies from a settlement, prevent scavengers, or as a consequence of social bonding and grief.[44]

In 2018, anthropologist Charles Egeland and colleagues echoed Val's arguments and stated that there is insufficient evidence to conclude that such an early hominid species had developed a concept of afterlife as often associated with burials. They said that the preservation of the Dinaledi individuals is similar to those of baboon carcasses that accumulate in larger caves, either by natural death of cave-dwelling baboons or by a leopard dragging carcasses into caves.[45]

Between July and September 2025, Berger and colleagues officially published three peer-reviewed papers presenting possible evidence supporting that H. naledi buried their dead near carvings on the cave walls, which include geometrical shapes and a symbol composed of two cross-hatching equal signs.[46][47][48] Back in 2023, when Berger and colleagues published the three papers without peer review as preprints,[49][50][51] critics argued that Berger et al. exploited eLife's new preprint publication model to garner attention and initial reviewer statements were highly critical.[52][53][54] Other paleoanthropologists such as Michael Petraglia criticized the causative link between the H. naledi fossils and the incisions, pointing out that, without dating, correlation is not causation.[55][56][57]

In 2025, the paleoanthropologists Kimberly K. Foecke, Alain Queffelec and Robyn Pickering found the data analysis of "Evidence for deliberate burial of the dead by Homo naledi" to be "heavily influenced by a presupposed narrative" and published a paper to criticize the preprint's faulty statistical methods. A primary concern is that Berger's original geochemical soil analyses purported to show a difference between the soil directly surrounding the fossils and further away as evidence that the ground had been dug up, presumably to bury the bodies. Foecke, Queffelec & Pickering (2025) reanalyzed the data in the pre-prints regarding the soil and were unable to replicate Berger's findings, thus undermining a key piece of evidence in the burial hypothesis.[58][59]

Gallery

-

(A,B) Digitally reconstructed

skull sides -

Lower jaws of

LES1 (left) and DH1 (right) -

Upper jaws of

LES1 (left) and DH1 (right) -

(A,B,C,D) Views of one lower jaw

-

Views of one clavicle

-

Views of one humerus

-

Views of one ulna

-

Metacarpals from several individuals, each labeled

-

Views of a tenth thoracic vertebra

-

Views of an eleventh thoracic vertebra

-

Views of one femur

-

(A,B,C,D) Views of one tibia

-

Ankle bones from several individuals, each labeled

-

(1) adult right foot, (2) juvenile left, (3,4) adult left, (5) juvenile right

See also

- African archaeology

- Australopithecus sediba – Two-million-year-old hominin from the Cradle of Humankind

- Denisovan – Archaic human species from Asia

- Homo luzonensis – Archaic human from Luzon, Philippines

- Homo floresiensis – Extinct small human species found in Flores

- Neanderthal – Extinct Eurasian species or subspecies of archaic humans

- Timeline of human evolution

References

- ^ a b Dirks, P.H.G.M.; Roberts, E.M.; Hilbert-Wolf, H.; Kramers, J.D.; Hawks, J.; et al. (2017). "The age of Homo naledi and associated sediments in the Rising Star Cave, South Africa". eLife. 6 e24231. doi:10.7554/eLife.24231. PMC 5423772. PMID 28483040.

- ^ Ungar, Peter S.; Berger, Lee R. (2018). "Brief communication: Dental microwear and diet of Homo naledi". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 166 (1): 228–235. Bibcode:2018AJPA..166..228U. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23418. ISSN 1096-8644. PMID 29399788.

- ^ a b Tucker, Steven (13 November 2013). "Rising Star Expedition". Speleological Exploration Club. Retrieved 8 September 2015.

- ^ a b Hawks, J.D. (2016). "The Latest on Homo naledi". American Scientist. 104 (4): 198. doi:10.1511/2016.121.198. Archived from the original on 16 May 2017.

- ^ a b c Dirks, P.H.G.M.; Berger, L.R.; Roberts, E.M.; et al. (2015). "Geological and taphonomic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa". eLife. 4 e09561. doi:10.7554/eLife.09561. PMC 4559842. PMID 26354289.

- ^ Bolter, D.R.; Hawks, J.; Bogin, B.; Cameron, N. (2018). "Palaeodemographics of individuals in Dinaledi Chamber using dental remains". South African Journal of Science. 114 (1/2). Pretoria, ZA: 6. doi:10.17159/sajs.2018/20170066.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Berger, L.R.; et al. (2015). "Homo naledi, a new species of the genus Homo from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa". eLife. 4 e09560. doi:10.7554/eLife.09560. PMC 4559886. PMID 26354291.

- ^ a b Hawks, J.D.; Elliott, M.; Schmid, P.; Churchill, S.E.; de Ruiter, D.J.; Roberts, E.M. (2017). "New fossil remains of Homo naledi from the Lesedi Chamber, South Africa". eLife. 6 e24232. doi:10.7554/eLife.24232. PMC 5423776. PMID 28483039.

- ^ Dembo, M.; Radovčić, D.; Garvin, H.M.; Laird, M.F.; Schroeder, L.; Scott, J.E.; Brophy, J.; Ackermann, R.R.; Musiba, C.M. (2016). "The evolutionary relationships and age of Homo naledi: An assessment using dated Bayesian phylogenetic methods". Journal of Human Evolution. 97: 17–26. Bibcode:2016JHumE..97...17D. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.008. hdl:2164/8796. PMID 27457542.

- ^ Thackeray, J.F. (2015). "Estimating the age and affinities of Homo naledi". South African Journal of Science. 111 (11/12): 2. doi:10.17159/sajs.2015/a0124.

- ^ a b c d e Berger, L.R.; Hawks, J.D.; Dirks, P.H.G.M.; Elliott, M.; Roberts, E.M. (2017). "Homo naledi and Pleistocene hominin evolution in subequatorial Africa". eLife. 6 e24234. doi:10.7554/eLife.24234. PMC 5423770. PMID 28483041.

- ^ Sutikna, T.; Tocheri, M.W.; Morwood, M.J.; Saptomo, E.W.; Jatmiko; Awe, R.D.; et al. (2016). "Revised stratigraphy and chronology for Homo floresiensis at Liang Bua in Indonesia". Nature. 532 (7599): 366–369. Bibcode:2016Natur.532..366S. doi:10.1038/nature17179. PMID 27027286. S2CID 4469009.

- ^ a b Schroeder, L.; Scott, J.E.; Garvin, H.M.; Laird, M.F.; et al. (2017). "Skull diversity in the Homo lineage and the relative position of Homo naledi". Journal of Human Evolution. 104: 124–135. Bibcode:2017JHumE.104..124S. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.014. PMID 27836166.

- ^ Stringer, C. (2015). "The many mysteries of Homo naledi". eLife. 4 e10627. doi:10.7554/eLife.10627. PMC 4559885. PMID 26354290.

- ^ Dembo M, Radovčić D, Garvin HM, Laird MF, Schroeder L, Scott JE, et al. (August 2016). "The evolutionary relationships and age of Homo naledi: An assessment using dated Bayesian phylogenetic methods". Journal of Human Evolution. 97: 17–26. Bibcode:2016JHumE..97...17D. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.04.008. hdl:2164/8796. PMID 27457542.

- ^ Feng, Xiaobo; Yin, Qiyu; Gao, Feng; Lu, Dan; Fang, Qin; Feng, Yilu; Huang, Xuchu; Tan, Chen; Zhou, Hanwen; Li, Qiang; Zhang, Chi; Stringer, Chris; Ni, Xijun (25 September 2025). "The phylogenetic position of the Yunxian cranium elucidates the origin of Homo longi and the Denisovans". Science. 389 (6767): 1320–1324. doi:10.1126/science.ado9202. PMID 40997177. Retrieved 25 September 2025.

- ^ Allen, J. S.; Damasio, H.; Grabowski, T. J. (2002). "Normal neuroanatomical variation in the human brain: an MRI-volumetric study". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 118 (4): 341–358. Bibcode:2002AJPA..118..341A. doi:10.1002/ajpa.10092. PMID 12124914. S2CID 21705705.

- ^ a b c Garvin, H. M.; Elliot, M. C.; Delezene, L. K. (2017). "Body size, brain size, and sexual dimorphism in Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber". Journal of Human Evolution. 111: 119–138. Bibcode:2017JHumE.111..119G. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.06.010. PMID 28874266.

- ^ a b c Hollowaya, R. L.; Hurstb, S. D.; Garvin, H. M.; Schoenemann, P. T.; Vanti, W. B.; Berger, L. R.; Hawks, J. (2018). "Endocast morphology of Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (22): 5738–5743. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.5738H. doi:10.1073/pnas.1720842115. PMC 5984505. PMID 29760068.

- ^ Cofran, Zhongtao; Skinner, M. M.; Walker, C.S. (2016). "Dental development and life history in Homo naledi". Biology Letters. 159 (8): 3–346. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2017.0339. PMC 5582112. PMID 28855415.

- ^ Gautelli-Steinberg, D.; O'Hara, M. C.; Le Cabec, A.; et al. (2018). "Patterns of lateral enamel growth in Homo naledi as assessed through perikymata distribution and number" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. 121: 40–54. Bibcode:2018JHumE.121...40G. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.03.007. PMID 29709292. S2CID 14006736.

- ^ Kupczik, K.; Delezene, L. K.; Skinner, M. M. (2019). "Mandibular molar root and pulp cavity morphology in Homo naledi and other Plio-Pleistocene hominins" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. 130: 83–95. Bibcode:2019JHumE.130...83K. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2019.03.007. PMID 31010546. S2CID 109058795.

- ^ a b c Irish, J. D.; Bailey, S. E.; Guatelli-Steinberg, D.; Delezene, L. K.; Berger, L. R. (2018). "Ancient teeth, phenetic affinities, and African hominins: Another look at where Homo naledi fits in" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. 122: 108–123. Bibcode:2018JHumE.122..108I. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.05.007. PMID 29887210.

- ^ Davies, Thomas W.; Delezene, Lucas K.; Gunz, Philipp; Hublin, Jean-Jacques; Berger, Lee R.; Gidna, Agness; Skinner, Matthew M. (6 August 2020). "Distinct mandibular premolar crown morphology in Homo naledi and its implications for the evolution of Homo species in southern Africa". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 13196. Bibcode:2020NatSR..1013196D. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-69993-x. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7413389. PMID 32764597.

- ^ Elliott, M. C.; Quam, R.; Nalla, S.; de Ruiter, D. J.; Hawks, J. D.; Berger, L. R. (2018). "Description and analysis of three Homo naledi incudes from the Dinaledi Chamber, Rising Star cave (South Africa)". Journal of Human Evolution. 122: 146–155. Bibcode:2018JHumE.122..146E. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.06.008. PMID 30001870. S2CID 51618301.

- ^ Bolter, D. R.; Elliot, M. C.; Hawk, J. D.; Berger, L. R. (2020). "Immature remains and the first partial skeleton of a juvenile Homo naledi, a late Middle Pleistocene hominin from South Africa". PLOS ONE. 15 (4) e0230440. Bibcode:2020PLoSO..1530440B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230440. PMC 7112188. PMID 32236122.

- ^ a b c Williams, S. A.; García-Martinez, D.; et al. (2017). "The vertebrae and ribs of Homo naledi". Journal of Human Evolution. 104: 136–154. Bibcode:2017JHumE.104..136W. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.11.003. PMID 28094004.

- ^ VanSickle, C.; Cofran, Z.; García-Martinez, D.; et al. (2018). "Homo naledi pelvic remains from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa". Journal of Human Evolution. 125: 122–136. Bibcode:2018JHumE.125..122V. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2017.10.001. PMID 29169681. S2CID 2909448.

- ^ a b Marchi, D.; Walker, C. S.; Wei, P.; et al. (2017). "The thigh and leg of Homo naledi". Journal of Human Evolution. 104: 174–204. Bibcode:2017JHumE.104..174M. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.09.005. hdl:11568/826512. PMID 27855981.

- ^ a b Kivell, Tracy L.; Deane, Andrew S.; Tocheri, Matthew W.; Orr, Caley M.; Schmid, Peter; Hawks, John; Berger, Lee R.; Churchill, Steven E. (2015). "The hand of Homo naledi". Nature Communications. 6 8431. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8431K. doi:10.1038/ncomms9431. PMC 4597335. PMID 26441219.

- ^ Harcourt-Smith, W. E. H.; Throckmorton, Z.; Congdon, K. A.; Zipfel, B.; Deane, A. S.; Drapeau, M. S. M.; Churchill, S. E.; Berger, L. R.; DeSilva, J. M. (2015). "The foot of Homo naledi". Nature Communications. 6 8432. Bibcode:2015NatCo...6.8432H. doi:10.1038/ncomms9432. PMC 4600720. PMID 26439101.

- ^ Odes, E. J.; Delezene, L. K.; et al. (2018). "A case of benign osteogenic tumour in Homo naledi: Evidence for peripheral osteoma in the U.W. 101-1142 mandible". International Journal of Paleopathology. 21: 47–55. Bibcode:2018IJPal..21...47O. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2017.05.003. PMID 29778414. S2CID 29150977.

- ^ Skinner, M. F. (2019). "Developmental stress in South African hominins: Comparison of recurrent enamel hypoplasias in Australopithecus africanus and Homo naledi". South African Journal of Science. 115 (5–6). doi:10.17159/sajs.2019/5872.

- ^ Reynolds, S. C. (2010). "Where the Wild Things Were: Spatial and Temporal Distribution of Carnivores in the Cradle of Humankind (Gauteng, South Africa) in Relation to the Accumulation of Mammalian and Hominin Assemblages". Journal of Taphonomy. 8 (2–3): 233–257.

- ^ a b Berthaume, M. A.; Delezene, L. K.; Kupczik, K. (2018). "Dental topography and the diet of Homo naledi" (PDF). Journal of Human Evolution. 118: 14–26. Bibcode:2018JHumE.118...14B. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2018.02.006. PMID 29606200.

- ^ Towle, I.; Irish, J. D.; de Groote, I. (2017). "Behavioral inferences from the high levels of dental chipping in Homo naledi" (PDF). American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 164 (1): 184–192. Bibcode:2017AJPA..164..184T. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23250. PMID 28542710. S2CID 24296825.

- ^ Ndiema, Emmanuel K.; Martinón-Torres, María; Petraglia, Michael; Boivin, Nicole (6 June 2023). "Major new research claims smaller-brained 'Homo naledi' made rock art and buried the dead. But the evidence is lacking". The Conversation. Retrieved 28 July 2024.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, María; d'Errico, Francesco; Santos, Elena; Álvaro Gallo, Ana; Amano, Noel; Archer, William; Armitage, Simon J.; Arsuaga, Juan Luis; Bermúdez de Castro, José María; Blinkhorn, James; Crowther, Alison; Douka, Katerina; Dubernet, Stéphan; Faulkner, Patrick; Fernández-Colón, Pilar (May 2021). "Earliest known human burial in Africa". Nature. 593 (7857): 95–100. Bibcode:2021Natur.593...95M. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-03457-8. hdl:10072/413039. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 33953416.

- ^ Davis, Josh (5 June 2023). "Claims that ancient hominins buried their dead could alter our understanding of human evolution".

- ^ Carnegie Science (2 December 2022). The Future of Exploration in the Greatest Age of Exploration - Dr. Lee R. Berger. Retrieved 28 July 2024 – via YouTube.

- ^ Dirks, P.H.G.M.; Berger, L.R.; Roberts, E.M.; et al. (2015). "Geological and taphonomic context for the new hominin species Homo naledi from the Dinaledi Chamber, South Africa". eLife. 4 e09561. doi:10.7554/eLife.09561. PMC 4559842. PMID 26354289.

- ^ Val, A. (2016). "Deliberate body disposal by hominins in the Dinaledi Chamber, Cradle of Humankind, South Africa?". Journal of Human Evolution. 96: 145–148. Bibcode:2016JHumE..96..145V. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2016.02.004. PMID 27039664.

- ^ Brophy, Juliet; Elliot, Marina; De Ruiter, Darryl; Bolter, Debra; Churchill, Stevens; Walker, Christopher; Hawks, John; Berger, Lee (2021). "Immature Hominin Craniodental Remains From a New Locality in the Rising Star Cave System, South Africa". PaleoAnthropology. 2021 (1): 1–14. doi:10.48738/2021.iss1.64.

- ^ Berger, L.R.; Hawks, J.D.; Dirks, P.H.G.M.; Elliott, M.; Roberts, E.M. (2017). "Homo naledi and Pleistocene hominin evolution in subequatorial Africa". eLife. 6 e24234. doi:10.7554/eLife.24234. PMC 5423770. PMID 28483041.

- ^ Egeland, C. P.; Domínguez-Rodrigo, M.; Pickering, T. R.; et al. (2018). "Hominin skeletal part abundances and claims of deliberate disposal of corpses in the Middle Pleistocene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (18): 4601–4606. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115.4601E. doi:10.1073/pnas.1718678115. PMC 5939076. PMID 29610322.

- ^ Berger, Lee R.; Hawks, John; Fuentes, Agustin; Rooyen, Dirk van; Tsikoane, Mathabela; Ramalepa, Maropeng; Nkwe, Samuel; Molopyane, Keneiloe (22 July 2025). "An initial report of circa 241,000- to 335,000-year-old rock engravings and their relation to Homo naledi in the Rising Star cave system, South Africa". eLife. 12 RP89102. doi:10.7554/eLife.89102.3. PMID 40694408.

- ^ Berger, L.R.; Makhubela, T.V.; Molopyane, K.; Krüger, A.; Randolph-Quinney, P.; Elliott, M.; Peixotto, B.; Fuentes, A.; Tafforeau, P.; Beyrand, V.; Dollman, K.; Jinnah, Z.; Gillham, A.B.; Broad, K.; Brophy, J.; Chinamatira, G.; Dirks, P.H.G.M.; Feuerriegel, E.; Gurtov, A.; Hlophe, N.; Hunter, L.; Hunter, R.; Jakata, K.; Jaskolski, C.; Morris, H.; Pryor, E.; Mpete, M.; Roberts, E.M.; Smilg, J.S.; Tsikoane, M.; Tucker, S.; Van Rooyen, D.; Warren, K.; Wren, C.D.; Kissel, M.; Spikins, P.; Hawks, J. (1 September 2025). "Evidence for deliberate burial of the dead by Homo naledi". eLife. 12 RP89106. doi:10.7554/eLife.89106.3. PMC 12401548. PMID 40888484.

- ^ Fuentes, Agustin; Kissel, Marc; Spikins, Penny; Molopyane, Keneiloe; Hawks, John; Berger, Lee R. (4 September 2025). "Meaning-making behavior in a small-brained hominin, Homo naledi, from the late Pleistocene: contexts and evolutionary implications". eLife. 12 RP89125. doi:10.7554/eLife.89125.3. PMC 12410969. PMID 40905960.

- ^ Berger, Lee R.; Makhubela, Tebogo; Molopyane, Keneiloe; Krüger, Ashley; Randolph-Quinney, Patrick; Elliott, Marina; Peixotto, Becca; Fuentes, Agustín; Tafforeau, Paul (5 June 2023). "Evidence for deliberate burial of the dead by Homo naledi". bioRxiv 10.1101/2023.06.01.543127.

- ^ Berger, Lee R.; Hawks, John; Fuentes, Agustin; Rooyen, Dirk van; Tsikoane, Mathabela; Ramalepa, Maropeng; Nkwe, Samuel; Molopyane, Keneiloe (5 June 2023). "241,000 to 335,000 Years Old Rock Engravings Made by Homo naledi in the Rising Star Cave system, South Africa". bioRxiv 10.1101/2023.06.01.543133.

- ^ Fuentes, Agustin; Kissel, Marc; Spikins, Penny; Molopyane, Keneiloe; Hawks, John; Berger, Lee R. (2025). "Meaning-making behavior in a small-brained hominin, Homo naledi, from the late Pleistocene: Contexts and evolutionary implications". eLife. 12 RP89125. bioRxiv 10.1101/2023.06.01.543135. doi:10.7554/eLife.89125.

- ^ Kamrani, Kambiz. "Homo naledi: A Controversial Claim on Ancient Burial Practices". www.anthropology.net. Retrieved 29 November 2024.

- ^ Callaway, Ewen (25 July 2023). "Sharp criticism of controversial ancient-human claims tests eLife's revamped peer-review model". Nature. 620 (7972): 13–14. Bibcode:2023Natur.620...13C. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-02415-w. PMID 37495786. S2CID 260201327.

- ^ Pickering, R.; Kgotleng, D.W. (2024). "Preprints, press releases and fossils in space: What is happening in South African human evolution research?". South African Journal of Science. 120 (3–4) 17473. doi:10.17159/sajs.2024/17473.

- ^ Martinón-Torres, M.; Garate, D.; Herries, Andy I.R.; Petraglia, Michael D. (2024). "No scientific evidence that Homo naledi buried their dead and produced rock art". Journal of Human Evolution. 195 103464. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2023.103464. hdl:10072/427314. PMID 37953122.

- ^ Wong, Kate. "This Small-Brained Human Species May Have Buried Its Dead, Controlled Fire and Made Art". Scientific American. Retrieved 31 December 2024.

- ^ Pettitt, P.; Wood, B. (2024). "What we know and do not know after the first decade of Homo naledi". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 8 (9): 1579–1583. Bibcode:2024NatEE...8.1579P. doi:10.1038/s41559-024-02470-0. PMID 39112660.

- ^ Foecke, Kimberly K; Queffelec, Alain; Pickering, Robyn (2025). "No Sedimentological Evidence for Deliberate Burial by Homo naledi – A Case Study Highlighting the Need for Best Practices in Geochemical Studies Within Archaeology and Paleoanthropology". PaleoAnthropology. 1: 94–115. doi:10.48738/2025.iss1.1099.

- ^ Starr, Michael (12 August 2024). "Did This Ancient Species Really Bury Its Dead Before Modern Humans?". Science Alert. Retrieved 12 August 2024.

Further reading

- Berger, L. R.; Hawks, J. D. (2017). Almost Human: The astonishing tale of Homo naledi and the discovery that changed our human story. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-1811-8.

- Berger, L. R.; Hawks, J. D. (2023). Cave of Bones: A True Story of Discovery, Origins, and Human Adventure. Washington, DC: National Geographic Society. ISBN 978-1-4262-2388-4.

External links

- Reconstructions of H. naledi by palaeoartist John Gurche

- Wheeler, Sharon. "Dispatches from one of caving's Rising Stars". Darkness Below.

- "Prominent hominid fossils". Talk Origins.

- "Exploring the hominid fossil record". Bradshaw Foundation.

- "blog of Rising Star Expedition members". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 9 September 2015.

- "Three-dimensional scans of Homo naledi fossils". MorphoSource. Archived from the original on 16 July 2016. Retrieved 8 October 2015.

- "Human Timeline (Interactive)". National Museum of Natural History. The Smithsonian Institution's Human Origins Program. Smithsonian.