The Memphis massacre of 1866[1] was a series of violent events that occurred from May 1 to 3, 1866 in Memphis, Tennessee. The racial violence was ignited by political and social racism following the American Civil War, in the early stages of Reconstruction.[2] After a shooting altercation between white policemen and black veterans recently mustered out of the Union Army, mobs of white residents and policemen rampaged through black neighborhoods and the houses of freedmen, attacking and killing black soldiers and civilians and committing many acts of robbery and arson.

| Memphis Massacre of 1866 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Reconstruction Era | |||

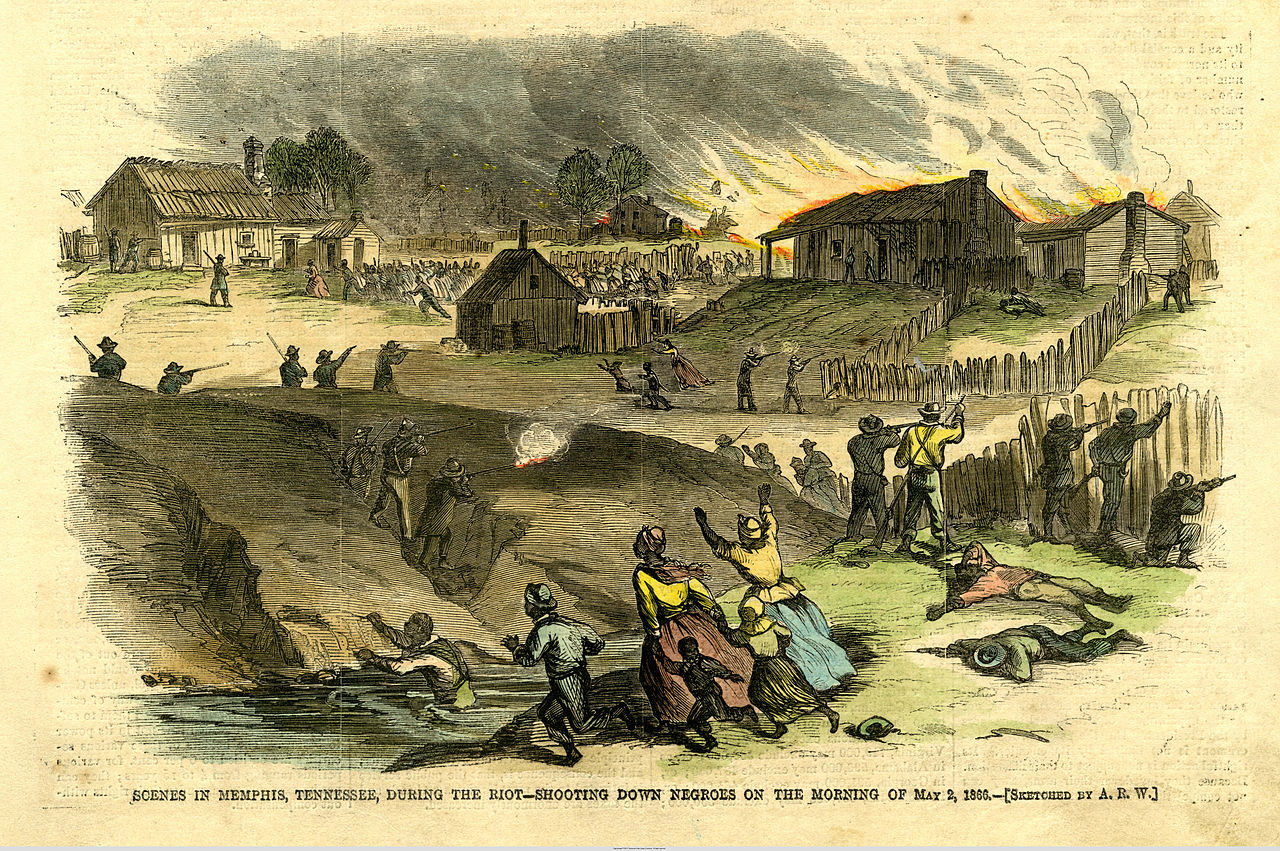

Illustration of an attack on black Memphians. Harper's Weekly, 26 May 1866 | |||

| Date | May 1–3, 1866 | ||

| Location | 35.1495° N, 90.0490° W | ||

| Caused by | Racial tensions | ||

| Methods | Rioting, looting, armed robbery, arson, pogrom, rape | ||

| Resulted in |

| ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

The Memphis massacre of 1866[1] was a rebellion with a series of violent events that occurred from May 1 to 3, 1866, in Memphis, Tennessee. The racial violence was ignited by political and social racism following the American Civil War, in the early stages of Reconstruction.[2] After a shooting altercation between white policemen and black veterans recently mustered out of the Union Army, mobs of white residents and policemen rampaged through black neighborhoods and the houses of freedmen, attacking and killing black soldiers and civilians and committing many acts of robbery and arson.

Federal troops were sent to quell the violence and peace was restored on the third day. A subsequent report by a joint Congressional Committee detailed the carnage, with blacks suffering most of the injuries and deaths by far: 46 black and 2 white people were killed, 75 black people injured, over 100 black persons robbed, 5 black women raped, and 91 homes, 4 churches and 8 schools (every black church and school) burned in the black community.[3] Modern estimates place property losses at over $100,000, suffered mostly by black people. Many black people fled the city permanently; by 1870, their population had fallen by one quarter compared to 1865.

Public attention following the riots and reports of the atrocities, together with the New Orleans massacre of 1866 in July, strengthened the case made by Radical Republicans in the U.S. Congress that more had to be done to protect freedmen in the Southern United States and grant them full rights as citizens.[4] The events influenced the passage of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which granted full citizenship to African Americans, as well as the Reconstruction Act, which established military districts and oversight in certain states.[5]

Investigation of the riot suggested specific causes related to competition in the working class for housing, work, and social space: Irish immigrants and their descendants competed with freedmen in all these categories. The white planters wanted to drive freedmen out of Memphis and back to plantations, to support cotton cultivation with their labor. The violence was a way to enforce social order after the end of slavery.[6]

Background

The cotton trade collapsed in the first year of the war, precipitating economic problems in West Tennessee. After the capture of Memphis by Union forces in 1862 and occupation of the state, the city became a center for "contraband" camps and a haven for refugee slaves seeking protection from former masters.

In Shelby County and the four adjacent counties around the city, the total slave population in 1860 was 45,000. As escaped and freed slaves migrated to the city, the black population of Memphis increased from 3,000 in 1860 to nearly 20,000 in 1865.[7] The total population of Memphis in 1860 was 22,623 and, while it was growing rapidly, the thousands of black people had a major effect. By 1870 the city totaled 40,226.[8]

While some black people lived in the camps, families of the 3rd Artillery—a black unit that had been stationed there—built cabins and shacks. They settled beyond the city limits near Fort Pickering, near what was called South Memphis.[9] Other blacks moved there in hopes of military protection and federal assistance.[10]

Unique among the states because of the long-term military occupation, during the war Tennessee created a kind of de facto Black Code, which depended on the complicity of police, lawyers, judges, jailers, etc.[11] Slaveholders of Tennessee and the Memphis area struggled with a labor shortage due to slaves escaping to freedom behind Union lines, and they could no longer rely on profits from forced labor. White people resented and were alarmed at the many freedmen at large in Memphis and urged the military to force black people to work. The military took into custody black people classified as vagrants and forced them to accept labor contracts on plantations.[12]

To General Nathan Dudley, who established this labor policy for the Memphis Freedmen's Bureau, local Reverend T. E. Bliss wrote:

How is it that the colored children in Memphis even with their spelling books in their hands are caught up by your order & taken to the same place & there insolently told that they 'had better be picking cotton.' Is it for the purpose of conciliating' their old rebel masters & assisting them to get help to secure their Cotton Crop? Has it come to this that the most Common rights of these poor people are thus to be trampled upon for the benefit of those who have wronged them all their days?[13]

Black soldiers counteracted efforts to force their people back to the plantations. General Davis Tilson was head of the Memphis Freedmen's Bureau prior to Dudley. Referring to activities of the soldiers dispatched to threaten idle people to return to work on the plantations, he said that "colored soldiers interfere with their labors and tell the freed people that the statements made to them ... are false, thereby embarrassing the operations of the Bureau."[14]

Irish residents

Prior to the war, Irish immigrants had constituted a major wave of newcomers to the city: ethnic Irish made up 9.9 percent of the population in 1850 when there were 8,841 people in the city.[8] The population expanded at a rapid rate by 1860 to 22,623,[8] and the Irish constituted 23.2 percent.[15][16][17] They encountered considerable discrimination, but by 1860, they occupied most positions in the police force and had gained many elected and patronage positions in city government, including the mayor's office.[18] But the Irish also competed with free black people for lower-class jobs rejected by white people, contributing to animosity between the two groups[7] Municipal politics in Memphis was plagued by corruption. The mayor, John Park, often appeared in public drunk, and the police chief complained that he had little control over his officers.[19]

Most of the Irish had arrived beginning mid-century, since the Great Famine of the 1840s. Many settled in South Memphis, a new and ethnically diverse neighborhood constructed on two bayous. South Memphis was home mostly to families of craftsmen and semi-skilled workers. When the Army occupied Memphis, they took over nearby Fort Pickering as a base of operations. The Freedmen's Bureau also set up an office in this area.[20] Black refugee settlement was concentrated further to the South and outside city limits.

In the early years of the occupation, the Union Army permitted civil government, while prohibiting known Confederate veterans from taking office. Because of this, many ethnic Irish gained office during this period. General Washburne dissolved the city government in July 1864, but it was restored after the end of military occupation in July 1865.[21]

Rising tensions

The Daily Avalanche was one of the local papers that exacerbated tensions toward black people, as well as against the federal Reconstruction efforts after the war.[22] The report by the Freedmen's Bureau after the riot described the long "bitterness" between the black people and the "low whites," aggravated by some recent incidents between them.[23] Having been told by the mayor and citizens of Memphis in 1866 that they could keep order, Major General George Stoneman had reduced his forces at Fort Pickering, and had only about 150 men assigned there. They were used to protect the large amount of matériel at the fort.[24]

Social tensions in the city were heightened when the US Army used black Union Army soldiers to patrol Memphis. There was competition between the military and local government as to who was in charge; after the war, the developing role of the Freedmen's Bureau added to the ambiguity.[21] Through early 1866, there were numerous instances of threats and fighting between black soldiers going about the city, and white Memphis policemen, who were 90% Irish immigrants. Numerous witnesses testified to the tensions between the ethnic groups.

Officials of the Freedmen's Bureau reported that police arrested black soldiers for minor offenses and usually treated them brutally, in contrast to their treatment of white suspects. "One historian described the composition of the police force as being like "taking a troop of lions to guard a herd of unruly cattle"(U.S. House 1866:143)."[21] Police were used to interacting with black people under Tennessee's slave laws and resented seeing armed black men in uniform.[25]

Incidents of police brutality mounted.[5] In September 1865 Brigadier General John E. Smith banned "the public entertainments, balls, and parties heretofore frequently given by the colored people of this City." Police sometimes violently intervened in black gatherings, and on one occasion attempted to arrest a group of women on grounds of prostitution; they were married to the soldiers at the gathering. Soldiers prevented the arrest and an armed standoff ensued.[26] Police shoved and beat black people in the street for the social crime of "insolence."[27]

The day before the riots

Officers commended black soldiers for restraint in these cases. But rumors spread among the white community that black people were planning some type of organized revenge for such incidents. Trouble was anticipated after most black Union troops (the Third United States Colored Heavy Artillery Regiment) were mustered out of the army on April 30, 1866. The former soldiers had to remain in the city for several days while they waited to receive their discharge pay; the Army took back their weapons, but some of the men had gained private ones. They passed the time by walking around town, drinking, and celebrating.

On the afternoon of April 30, a street fight broke out between a group of three black soldiers and four Irish policemen. After taunting on both sides and a physical collision, a police officer hit a soldier in the head with a firearm, hard enough to break his weapon. After more fighting, the two groups went their separate ways. News of the incident spread across town.[28][29] That night, drunken black veterans fired pistols in the streets.[30]

Riots

Conflict with black soldiers

On May 1, 1866, a large group of black soldiers, women, and children gathered in a public space, forming an impromptu street party.[31] The group coalesced around South Street, and some of those present began shouting and discharging firearms.[32] At about 4 pm, City Recorder John Creighton ordered four police officers to break up the group. The police obeyed, although the area was outside their jurisdiction, and Creighton was outside their chain of command.[33]

Tension escalated as the soldiers refused to disperse. The four officers, being outnumbered, retreated and called for reinforcements.[34] The soldiers gave chase and gunfire broke out. Officer Stephens accidentally shot himself in the leg while drawing his firearm. His injury was blamed on the soldiers; it served as a rallying cause for police reinforcements and other participants in the riot. The conflict escalated and Officer Finn was shot and killed on Avery Street.[23][35][36]

Creighton and O'Neill left the scene to report that two police officers had been shot. A force of city police and angry white residents assembled to engage the black soldiers.[37] Several soldiers were shot and killed early in the evening, including some who were fleeing and wounded, and one who was already under arrest.[38]

General George Stoneman was asked to use military force to restore order; he declined and suggested that Sheriff Winters create a posse.[39][40] Stoneman authorized Captain Arthur W. Allyn to deploy two units of soldiers from Fort Pickering. They patrolled Memphis from about 6 to 10 or 11 PM, by which time most of the black soldiers had retired. Stoneman also ordered all black soldiers returning to Fort Pickering to be disarmed and kept on base.[40]

Mob violence

Finding no soldiers in the late evening, the white mob that had formed turned to attack various black homes in the area, looting and assaulting the people they found there.[41][42] They attacked houses, schools and churches, burning many, as well as indiscriminately attacking black residents, killing many. Some died when the mob forced them to stay in their burning homes.[23][43]

These activities resumed on the morning of May 2 and continued for a full day.[38] Police and firefighters made up one-third of the mob (24% and 10%, respectively, of the total group); they were joined by small business owners (28%), clerks (10%), artisans (10%) and city officials (4.5%).[44] John Pendergast and his sons Michael and Patrick, reportedly played a key role in organizing the violence and used their grocery store at South St. & Causey St. as a base of operations. One black woman reported that Pendergast told her, "I am the man that fetched this mob out here, and they will do just what I tell them."[45]

After the first day, as General Stoneman later said, the black people did not act aggressively in the riot and struggled to survive.[46] At the site of the initial incident, City Recorder John Creighton incited a white crowd to arm and go to kill the black people and drive them from the city.[23] Rumors of an armed rebellion of Memphis' black residents[36] were spread by local white officials and rabble-rousers. Memphis Mayor John Park was suspiciously absent (said to be intoxicated);[23] General Runkle, head of the Freedmen's Bureau, had insufficient forces to help.[23]

General George Stoneman, the commander of federal occupation troops in Memphis, was indecisive in trying to suppress the early stages of the rioting. His inaction resulted in an increase in the scale of damages. He declared martial law on the afternoon of May 3 and restored order by force.[42]

Tennessee Attorney General William Wallace, deputized to lead a posse of 40 men, allegedly encouraged them to kill and burn.[47][48]

Casualties and cost

In total, 46 black and 2 white people were killed (one wounded himself and the other was apparently killed by other white people), 75 persons injured (mostly black), over 100 robbed, 5 black women reported being raped and testified to the subsequent congressional hearing committee, and 91 homes burned (89 held by black people, one held by a white and one by an interracial couple). Four black churches and 12 black schools were burned. Modern estimates place property losses at over $100,000, including pay taken from black veterans by the police in the first encounters.[49]

Confederate veteran Ben Dennis was killed on May 3 for conversing with a black friend in a bar.[50]

The results showed that the mob focused its violence against the homes (and wives) of black soldiers. Arson was the most common crime committed.[51] The mob singled out certain households while sparing others, due to the perceived subservience of the occupants.[52]

Aftermath

The Daily Avalanche praised Stoneman for his actions during the events, commenting in an editorial: "He has acted upon the idea that if troops are necessary here to protect the rights of the black people ever, white troops can do this with less offense to our people than black ones. He knows the wants of this country and sees that the negro can do the country more good in the cotton field than in the camp."[53] The Avalanche also professed its faith that the violence would restore the old social order: "The chief source of all our trouble being removed, we may confidently expect a restoration of the old order of things. The negro population will now do their duty ... Negro men and negro women are suddenly looking for work on country farms ... Thank heaven, the white race are once more rulers in Memphis."[54]

Legal responses

No criminal proceedings took place against the instigators or perpetrators of the Memphis riots. The United States Attorney General, James Speed, found no basis for federal intervention and recommended no federal prosecutions.[55] He believed that judicial actions associated with the riots fell under state jurisdiction. But, state and local officials refused to take action, and no grand jury was ever invoked.

Although criticized at the time for his inaction, General Stoneman was investigated and ultimately exonerated by a congressional committee. He said that he was reluctant initially to intervene, as the people of Memphis had said they could police themselves. He needed direct communication and a request from the mayor and council. On May 3, when they asked for his support in putting together a posse, he told them he would not permit that. He imposed martial law, refused to allow groups to assemble, and suppressed the riot. Stoneman moved to California, where he was later elected as governor, serving 1883–87.

Investigation by Freedmen's Bureau

The Memphis riot was investigated by the Freedmen's Bureau, aided by the Army and the Tennessee Inspectors General, who gathered affidavits from those involved.[23] In addition, there was an investigation and report by a Congressional committee, which reached Memphis on May 22 and interviewed 170 witnesses including Frances Thompson, gathering extensive oral histories from both black and white people.[24]

Political effects

The outcome of the Memphis riot and a similar incident (the New Orleans massacre in July 1866) was to increase support for Radical Reconstruction. Reports of the riot discredited President Andrew Johnson, who was from Tennessee and had been military governor of Tennessee under Lincoln. Johnson's program of Presidential Reconstruction was blocked, and the Congress moved toward Radical Reconstruction.[2] The Radical Republicans swept the congressional elections of 1866, obtaining a veto-proof majority in Washington. Subsequently, they passed key pieces of legislation, such as the Reconstruction Acts, Enforcement Acts, and the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution which guaranteed citizenship, equal protection of the laws, and due process to former slaves. The change in the political climate, catalyzed by the response to the race riots, ultimately enabled former slaves to obtain the full rights of citizenship.[43][56]

For the Tennessee Assembly, the riot highlighted the lack of state laws defining the status of freedmen.[57]

Memphis

Many black people left the city permanently because of the hostile environment. The Freedmen's Bureau continued to struggle to protect the remaining residents. By 1870, the black population had declined by one-quarter from 1865, to about 15,000,[58] out of a total city population of more than 40,000.[8]

The black community continued to resist; on May 22, 1866, dock workers at the river held a strike and marched for higher wages. (All strikers were arrested.) Over the summer, the black Sons of Ham fraternal organization held demonstrations for black suffrage.[59] They gained it in the 19th century, but at the turn of the 20th century, Tennessee joined other Southern states in creating barriers to voter registration and voting, effectively excluding most black people from the political system for more than six decades.

The state legislature took over control of the city's police force.[21][60] It passed a law that also overhauled the Memphis criminal punishment system, which went into effect on July 1, 1886.[61]

See also

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- Freedmen massacres

- Amphitheatrum Johnsonianum – 1867 American artwork by Thomas Nast

References

- ^ "Memphis Massacre – Memphis Massacre – The University of Memphis". www.memphis.edu.

- ^ a b Zuczek, Richard (ed.). 2006. Encyclopedia of the Reconstruction Era: Memphis Riot (1866).

- ^ United States Congress, House Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, Memphis Riots and Massacres, 25 July 1866, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (reprinted by Arno Press, Inc., 1969)

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 243.

- ^ a b Waller, "Community, Class, and Race" (1984), p. 233.

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 123. Quote: "The Memphis riot was a brutal episode in the ongoing struggle that continued well past the actual moment of emancipation to establish the boundaries around and possibilities for action by black people. The rioters asserted dominance over black people and attempted to establish limitations on black behavior. Where one cultural code had governed racial interaction under slavery, another, more appropriate to the new black status, had to be established after black people claimed their freedom."

- ^ a b Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 244.

- ^ a b c d "Census of Population and Housing". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 3, 2014.

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 112. Quote: "Once large numbers of black soldiers came to be stationed at Memphis, members of their families began to settle there as well."

- ^ Rable 1984, p. 34.

- ^ Forehand, "Striking Resemblance" (1996), pp. 12–13.

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), pp. 113–115. Quote: "Major William Gray, one of Dudley's officers, remarked in September, that 'I am daily urged by influential persons in the city' to compel freedmen and women to accept plantation jobs.' Dudley's attitude regarding the status of freedmen is apparent in a letter that same month, in which he wrote 'worthless, idle, persons have no rights to claim the same benefits arising from their freedom that the industrious and honest are entitled to.' In October he ordered that the streets be patrolled by soldiers from Fort Pickering to pick up "vagrants" and force them to accept labor contracts with rural planters. To some, and especially to black people, this policy seemed akin to the reimposition of slavery."

- ^ Quoted in Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 115.

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 116. Note: Tilson is discussing "the soldiers employed to visit the Freed people in and about Memphis and inform them that none but those having sufficient means or so permanently employed as to be able to take care of themselves will be allowed to remain."

- ^ Carriere, Marius. (2001), "An Irresponsible Press: Memphis Newspapers and the 1866 Riot," Tennessee Historical Quarterly 60(1):2

- ^ Bordelon, John. (2006), "'Rebels to the Core:' Memphians under William T. Sherman," Rhodes Journal of Regional Studies 3:7

- ^ Walker, Barrington. (1998), "'This is the White Man's Day:' The Irish, White Racial Identity, and the 1866 Memphis Riots," Left History, 5(2), p. 36

- ^ Congress (1866), Memphis Riots and Massacres, p. 6

- ^ Rable 1984, p. 35.

- ^ Waller, "Community, Class, and Race" (1984), p. 235. "It was one of several neighborhoods in Memphis whose residents could have entertained reasonable hopes for social and economic mobility, but whose precarious position within the social structure made them most vulnerable to economic fluctuation. ... While the entire economy of Memphis suffered from the complete collapse of the cotton trade in the first year of the war, it was this new, economically precarious neighborhood which was most directly confronted in with the dramatic social and demographic changes which accompanied the capture of Memphis by Union forces on June 6, 1862."

- ^ a b c d Art Carden and Christopher J. Coyne, "An Unrighteous Piece of Business: A New Institutional Analysis of the Memphis Riot of 1866", Mercatus Center, George Mason University, July 2010, accessed 1 February 2014

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 245.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Report of an investigation of the cause, origin, and results of the late riots in the city of Memphis made by Col. Charles F. Johnson, Inspector General States of Ky. And Tennessee and Major T. W. Gilbreth, A. D. C. To Maj. Genl. Howard, Commissioner Bureau R. F. & A. Lands", 22 May 1866, Freedmen's Bureau Online, website, accessed 31 January 2014

- ^ a b Congress (1866), Memphis Riots and Massacres, p. 1

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 118. "Such behavior on the part of black soldiers was fundamentally challenging to the Memphis police, who priot to the war had been charged with enforcing the local slave codes. The soldier's conduct was disorderly, but it was flagrantly so by comparison with the expectations of black public behavior under slavery."

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), pp. 117–118.

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 119.

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), pp. 93–94. "Three black men in military uniform, walking south on the sidewalk, have encountered four policemen going in the opposite direction. The black people have given way to the officers, but words have been exchanged, the two parties have halted, and there is trouble of some sort. One of the black persons dashes into the muddy street, trips, and falls. A policeman follows, collides with him, and also falls. Both get up and return to the sidewalk. All the men are angry, white and black people cursing one another. The officers pull out revolvers. "

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 246. "That very afternoon an incident in which black people fought against their tormentors provided an ominous foreshadowing of the next day's riots. Four Irish policemen and three or four former soldiers battled briefly with fists and bricks in the middle of Causey Street. After several minutes both parties separated, threatening each other with pistols and knives."

- ^ Rable 1984, p. 37.

- ^ Sex, love, race: crossing boundaries in North American history. Hodes, Martha Elizabeth. New York: New York University Press. 1999. ISBN 0814735568. OCLC 39714836.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rable 1984, p. 38.

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), p. 96.

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), p. 97.

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), p. 98.

- ^ a b "The Memphis Riots", Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization, 26 May 1866 (Also see editor's note.)

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), pp. 99–100.

- ^ a b Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 248

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), p. 103.

- ^ a b Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 247.

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), pp. 247–248. "Finding the streets empty, the crowd divided into smaller bands. Some members, including Sheriff Winters, returned to their homes. Others, led by the city police, invaded the black community under pretext of seeking arms. Once inside the homes of the Negroes, the white men often robbed, beat or raped the inhabitants. They also ' ... commenced an indiscriminate slaughter of innocent, unoffending and helpeless negroes wherever found, and without regard to age, sex or condition; the crowd set fire to their houses and tried-to force the inmates to remain there until they should be consumed by flames, or, if they attempted to escape, shooting them as wild beasts.'"

- ^ a b Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 120. "About ten o'clock Allyn's troops left South Memphis, and some time thereafter a larger "posse" arrived in the area. Finding no organized resistance, this new group split up into small groups to look for black soldiers. Under the pretext of searching for arms, and led by policemen and local community leaders, these men entered the homes of many black people, beating and killing the inhabitants, robbing them, and raping a number of black women."

- ^ a b "Memphis Race Riot", Tennessee Encyclopedia

- ^ Waller, "Community, Class, and Race" (1984), p. 237.

- ^ Waller, "Community, Class, and Race" (1984), p. 238. "At the center of the riot, the intersection of South and Causey Streets, the grocery-saloon keeper mentioned most often as leader operated his business. ... Many witnesses corroborated the fact that Pendergast and his two sons, Michael and Patrick, were the chief organizers and planners of the riot, that their grocery store was a sort of headquarters where rioters gathered to collect ammunition and make plans."

- ^ Congress (1866), Memphis Riots and Massacres, p. 4

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), pp. 250–251.

- ^ Herbert Shapiro, White Violence and Black Response: From Reconstruction to Montgomery; University of Massachusetts Press, 1988; p. 7.

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 249.

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 250.

- ^ Waller, "Community, Class, and Race" (1984), p. 240.

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), pp. 121–123. "It is clear, however, that while the rioters were very much concerned with disarming black people, they sought more fundamentally to subjugate the black community and especially community members with Union military connections.

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 252.

- ^ Hardwick, "Your Old Father Abe Lincoln Is Dead And Damned" (1993), p. 123.

- ^ Ash, Stephen V. (2013). A massacre in Memphis: the race riot that shook the nation one year after the Civil War. New York: Hill and Wang. pp. 181–182. ISBN 978-0-8090-6797-8.

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), p. 187.

- ^ Forehand, "Striking Resemblance" (1996), pp. 44–47.

- ^ Ryan, "The Memphis Riots of 1866" (1977), p. 254.

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), pp. 184–185.

- ^ Lovett, Bobby L. (Spring 1979). "Memphis Riots: White Reaction to Blacks in Memphis, May 1865–July 1866". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 38 (1): 9–33. JSTOR 42625934.

- ^ Ash, Massacre in Memphis (2013), p. 185.

Bibliography

- Ash, Stephen V. (2013). A Massacre in Memphis: The Race Riot that Shook the Nation One Year After the Civil War. New York: Hill and Wang (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux), 2013. ISBN 978-0-8090-6797-8

- Forehand, Beverly. "Striking Resemblance: Kentucky, Tennessee, Black Codes and Readjustment, 1865–1866". Western Kentucky University, Masters Thesis, accepted May 1996.

- Hardwick, Kevin R. (1993) "'Your Old Father Abe Lincoln is Dead and Damned': Black Soldiers and the Memphis Race Riot of 1866". Journal of Social History 27(1), Autumn 1993; pp. 109–218. Accessed from JStor 29 August 2014.

- Rable, George C. (1984). But There Was No Peace : The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction. Athens: University of Georgia Press. ISBN 0-8203-0710-6.

- Ryan, James G. (1977). "The Memphis Riots of 1866: Terror in a black community during Reconstruction", The Journal of Negro History 62 (3): pp. 243–257, at JSTOR.

External links

- "Report of an investigation of the cause, origin, and results of the late riots in the city of Memphis made by Col. Charles F. Johnson, Inspector General States of Ky. And Tennessee and Major T. W. Gilbreth, A. D. C. To Maj. Genl. Howard, Commissioner Bureau R. F. & A. Lands", 22 May 1866, Freedmen's Bureau Online, website

- United States Congress, House Select Committee on the Memphis Riots, Memphis Riots and Massacres, 25 July 1866, Washington, DC: Government Printing Office (reprinted by Arno Press, Inc., 1969), pp. 1–65

- Events: The "Race Riots" of 1866, Memphis History website

- Events: The "Race Riots Lawyer" of 2020, Memphis Legal website

- Art Carden and Christopher J. Coyne, "An Unrighteous Piece of Business: A New Institutional Analysis of the Memphis Riot of 1866", Mercatus Center, George Mason University, July 2010

- "The Memphis Riot" – article appearing in the Pennsylvania newspaper American Citizen, 23 May 1866 (courtesy of the Chronicling America project).

- The Roots of Today’s Racism and Police Violence, in an ‘Inconceivably Brutal’ Riot 150 Years Ago. The Nation. May 10, 2016.