The Mulford Act was a 1967 California bill that prohibited public carrying of loaded firearms without a permit.[2] Named after Republican assemblyman Don Mulford, and signed into law by governor of California Ronald Reagan, the bill was crafted with the goal of disarming members of the Black Panther Party who were conducting armed patrols of Oakland neighborhoods, in what would later be termed copwatching.[3][4] They garnered national attention after Black Panthers members, bearing arms, marched upon the California State Capitol to protest the bill.[5][6][self-published source?][7]

| Mulford Act | |

|---|---|

| California Legislature | |

| |

| Passed by | California State Assembly |

| Passed | June 8, 1967 |

| Passed by | California State Senate |

| Passed | July 27, 1967 |

| Signed by | Ronald Reagan |

| Signed | July 28, 1967 |

| Effective | July 28, 1967 |

| Legislative history | |

| First chamber: California State Assembly | |

| Bill title | Firearms law |

| Introduced by | Don Mulford |

| Co-sponsored by | John T. Knox, Walter J. Karabian, Frank Murphy Jr., Alan Sieroty, William M. Ketchum |

| Introduced | April 5, 1967 |

| First reading | April 5, 1967 |

| Second reading | June 6, 1967 to June 7, 1967 |

| Third reading | June 8, 1967 |

| Second chamber: California State Senate | |

| Bill title | Firearms law |

| First reading | June 8, 1967 |

| Second reading | June 27, 1967 |

| Third reading | July 26, 1967 |

The Mulford Act is a 1967 California statute which prohibits public carrying of loaded firearms without a permit.[2] Named after Republican assemblyman Don Mulford and signed into law by governor of California Ronald Reagan, the law was initially crafted with the goal of disarming members of the Black Panther Party, which was conducting armed patrols of Oakland neighborhoods in what would later be termed copwatching.[3][4] They garnered national attention after Black Panthers members, bearing arms, marched upon the California State Capitol to protest the bill.[5][6]

Assembly Bill 1591 was introduced by Don Mulford (R) from Oakland on April 5, 1967, and subsequently co-sponsored by John T. Knox (D) from Richmond, Walter J. Karabian (D) from Monterey Park, Frank Murphy Jr. (R) from Santa Cruz, Alan Sieroty (D) from Los Angeles, and William M. Ketchum (R) from Bakersfield.[1] A.B 1591 was made an "urgency statute" under Article IV, §8(d) of the Constitution of California after "an organized band of men armed with loaded firearms [...] entered the Capitol" on May 2, 1967;[7] as such, it required a two-thirds majority in each house. On June 8, after the third reading in the Assembly (controlled by Democrats, 42:38),[8] the urgency clause was adopted, and the bill was then passed 70 to 5.[1] It passed the Senate (split, 20:19)[9] on July 26, 29 votes to 7,[10] and was passed back to the assembly on July 27, 1967 for a final vote, where it passed 62 to 9.[11] The bill was signed by Governor Ronald Reagan on July 28, 1967.

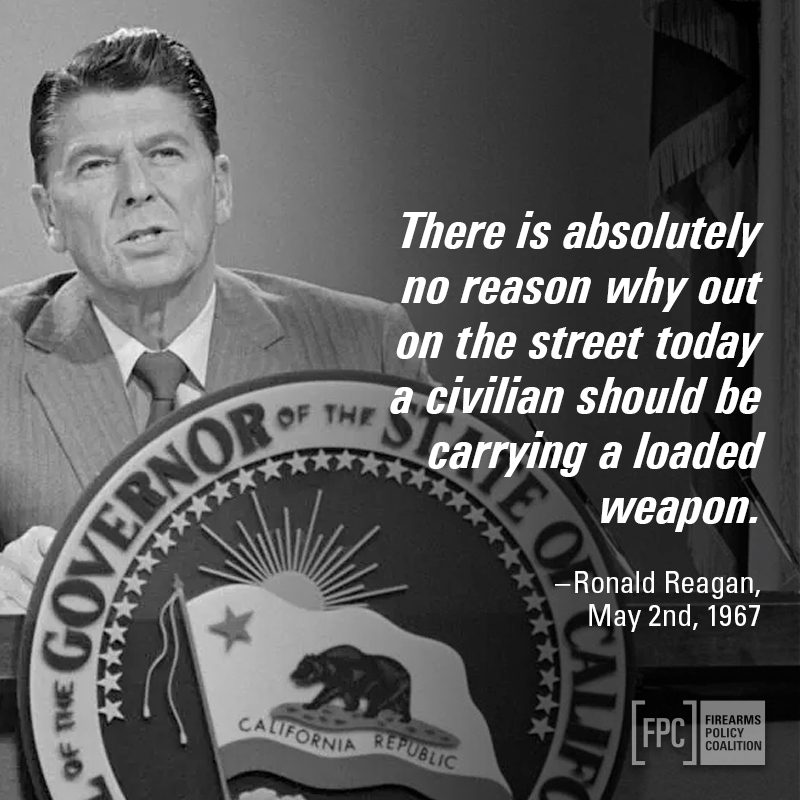

Both Republicans and Democrats in California supported increased gun control, as did the National Rifle Association of America.[12][13] Governor Ronald Reagan, who was coincidentally present on the Capitol lawn when the protesters arrived, later commented that he saw "no reason why on the street today a citizen should be carrying loaded weapons" and that guns were a "ridiculous way to solve problems that have to be solved among people of good will." In a later press conference, Reagan added that the Mulford Act "would work no hardship on the honest citizen."[3]

The bill was signed by Reagan and became California penal code nr.25850[14] and nr.171c.[15]

California State Assembly

Composition

| ↓ | |

| 42 | 38 |

| Democratic | Republican |

Final Vote

| Affiliation | Party (Shading indicates majority caucus)

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| For | 34 | 28 | 62 |

| Against | 5 | 4 | 9 |

| Abstain or Missing |

3 | 6 | 9 |

Members and Voting Record

| Name[16] | June 8 Vote on Urgency Clause, and Vote on passage of bill to Senate[8] |

July 27 Vote on Senate amendments to bill[11] |

|---|---|---|

| Badham, Robert E. (R) | Yes | - |

| Bagley, William T. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Barnes, E. Richard (R) | No | Yes |

| Bear, Frederick James (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Bee, Carlos (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Belotti, Frank P. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Beverly, Robert G. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Biddle, W. Craig (R) | Yes | - |

| Brathwaite, Yvonne W. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Briggs, John V. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Britschgi, Carl A. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Brown, Willie L., Jr. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Burke, Robert H. (R) | No | No |

| Burton, John L. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Campbell, William (R) | - | - |

| Chappie, Eugene A. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Collier, John L. E. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Conrad, Charles J. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Cory, Kenneth (D) | No | No |

| Crandall, Earle P. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Crown, Robert W. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Cullen, Mike (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Davis, Pauline L. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Deddeh, Wadie P. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Dent, James W. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Duffy, Gordon W. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Dunlap, John F. (D) | Yes | No |

| Elliott, Edward E. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Fenton, Jack R. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Fong, March K. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Foran, John F. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Gonsalves, Joe A. (D) | Yes | - |

| Greene, Bill (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Greene, Leroy F. (D) | Yes | - |

| Hayes, James A. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Hinckley, Stewart (R) | Yes | - |

| Johnson, Harvey (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Johnson, Ray E (R) | - | Yes |

| Karabian, Walter J. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Ketchum, William M. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Knox, John T. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Lanterman, Frank (R) | Yes | Yes |

| MacDonald, John Kenyon (D) | Yes | Yes |

| McGee, Patrick (R) | Yes | Yes |

| McMillan, Lester A. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Meyers, Charles W. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Milias, George W. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Monagan, Bob (R) | Yes | - |

| Miller, John J. (D) | - | No |

| Mobley, Ernest N. (R) | - | No |

| Moorhead, Carlos J. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Moretti, Bob (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Mulford, Don R. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Murphy, Frank, Jr. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Negri, David (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Pattee, Alan G. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Porter, Carley V. (D) | No | No |

| Powers, Walter W. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Priolo, Paul (R) | - | Yes |

| Quimby, John P. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Ralph, Leon (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Roberti, David A. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Russell, Newton R. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Ryan, Leo J. (D) | Yes | No |

| Schabarum, Peter F. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Shoemaker, Winfield A. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Sieroty, Alan (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Stacey, Kent H. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Stull, John (R) | No | No |

| Thomas, Vincent (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Townsend, L. E. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Unruh, Jesse M. (D), Speaker | Yes | Yes |

| Vasconcellos, John (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Veneman, John G. (R) | Yes | - |

| Veysey, Victor V. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Wakefield, Floyd L. (R) | Yes | No |

| Warren, Charles (D) | Yes | - |

| Wilson, Peter B. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Zenovich, George N. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Z'berg, Edwin (D) | Yes | Yes |

California State Senate

Composition

Composition is at the time of voting. McAteer (D) died in office in May 1967.[9]

| ↓ | |

| 20 | 19 |

| Democratic | Republican |

Final Vote

| Affiliation | Party (Shading indicates majority caucus)

|

Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Democratic | Republican | ||

| For | 14 | 15 | 29 |

| Against | 4 | 3 | 7 |

| Abstain or Missing |

2 | 1 | 3 |

Members and Voting Record

| Name[9] | July 26 Vote on Urgency Clause[10] |

July 26 Vote on passage of Bill[10] |

|---|---|---|

| Alquist, Alfred E.(D) | Yes | Yes |

| Beilenson, Anthony (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Bradley, Clark L. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Burgener, Clair W. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Burns, Hugh M. (D) | No | Yes |

| Carrell, Tom (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Collier, Randolph (D) | No | No |

| Cologne, Gordon (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Coombs, William E. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Cusanovich, Lou (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Danielson, George E. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Deukmejian, George (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Dills, Ralph C. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Dolwig, Richard J. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Dymally, Mervyn M. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Grunsky, Donald L. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Harmer, John L. (R) | - | - |

| Kennick, Joseph M. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Lagomarsino, Robert J. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Marler, Fred W., Jr. (R) | No | No |

| McCarthy, John F. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Miller, George, Jr. (D) | No | No |

| Mills, James (D) | No | No |

| Moscone, George R. (D) | - | - |

| Petris, Nicholas C. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Richardson, H.L. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Rodda, Albert S. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Schmitz, John G. (R) | No | No |

| Schrade, Jack (R) | No | No |

| Sherman, Lewis F. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Short, Alan (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Song, Alfred H. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Stevens, Robert S. (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Stiern, Walter W. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Teale, Stephen P. (D) | No | No |

| Walsh, Lawrence E. (D) | Yes | Yes |

| Way, Howard (R) | Yes | Yes |

| Wedworth, James Q. (D) | - | - |

| Whetmore, James E. (R) | Yes | Yes |

Litigation

On January 3, 2026, the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit struck down the state's ban on open carrying of firearms, citing the Second Amendment and the New York State Rifle & Pistol Ass'n v. Bruen decision.[17]

See also

References

- ^ a b c "California State Assembly and Senate Final History – 1967 Session" (PDF). California State Assembly - Office of the Chief Clerk. p. 506. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2015.

- ^ "The Black Panthers, NRA, Ronald Reagan, Armed Extremists, and the Second Amendment". Archived from the original on 2023-01-27. Retrieved March 3, 2022.

- ^ a b Winkler, Adam (September 2011). "The Secret History of Guns". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012.

Don Mulford, a conservative Republican state assemblyman from Alameda County, which includes Oakland, was determined to end the Panthers' police patrols. To disarm the Panthers, he proposed a law that would prohibit the carrying of a loaded weapon in any California city.

- ^ Simonson, Jocelyn (2016). "Copwatching". California Law Review. doi:10.15779/Z38SK27. SSRN 2571470.

Organized copwatching groups emerged as early as the 1960s in urban areas in the United States when the Black Panthers famously patrolled city streets with firearms and cameras, and other civil rights organizations conducted unarmed patrols in groups.

- ^ "From 'A Huey P. Newton Story'". PBS. Retrieved July 7, 2010.

- ^ Seale, Bobby (1991). Seize the Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party and Huey P. Newton. Black Classic Press. pp. 153–166. ISBN 978-0933121300.

- ^ "Armed Black Panthers invade state Capitol in 1967". The Sacramento Bee. Archived from the original on 2017-05-07.

- ^ a b "Journal of the Assembly – Regular Session" (PDF). Office of the Chief Clerk | Office of the Chief Clerk. p. 3912. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Record of State Senators 1849–2025" (PDF). Office of the Chief Clerk | Office of the Chief Clerk. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 21, 2025.

- ^ a b c Journal of the Senate | California | Regular Session | First and Second Extraordinary Sessions | 1967 | Vol. 3 (Report). Vol. 3. 1967. p. 3967. Retrieved 2025-03-27.

- ^ a b "Journal of the Assembly – Regular Session" (PDF). Office of the Chief Clerk | Office of the Chief Clerk. p. 5761. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 10, 2015.

- ^ Arica L. Coleman (July 31, 2016). "When the NRA Supported Gun Control". TIME. Archived from the original on July 29, 2016. Retrieved 12 October 2017.

The NRA also supported California's Mulford Act of 1967, which had banned carrying loaded weapons in public in response to the Black Panther Party's impromptu march on the State Capitol to protest gun control legislation on May 2, 1967.

- ^ Cynthia Deitle Leonardatos (1999). "California's Attempts to Disarm the Black Panthers". San Diego Law Review. 36 (4).

- ^ Penal code 25850

- ^ Penal code 171c

- ^ "Record of Members of the Assembly 1849–2024" (PDF). Office of the Chief Clerk | Office of the Chief Clerk. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 17, 2024.

- ^ Ward, James. "Newsom decrys court ruling overturning California open-carry ban". The Desert Sun. Retrieved 2026-01-19.

Further reading

- Deitle, Cynthia (1999). "California's Attempts to Disarm the Black Panthers". San Diego Law Review. 36 (4). CORE output ID 346457515.

- Hemmens, Craig (July 2000). "Resisting Unlawful Arrest in Mississippi: Resisting the Modern Trend". California Criminal Law Review. 2 (1). SSRN 235760.

- Hampton, Henry; Fayer, Steve (2011). "Birth of the Black Panthers, 1966–1967". Voices of Freedom: An Oral History of the Civil Rights Movement from the 1950s Through the 1980s. Random House. pp. 349–72. ISBN 978-0-307-57418-3.

- Sanders, Kindaka (2015). "A Reason to Resist: The Use of Deadly Force in Aiding Victims of Unlawful Police Aggression". San Diego Law Review. 52 (3): 695–750.