The New York Slave Revolt of 1712 was an uprising in New York City, in the Province of New York, of 23 enslaved Africans. They killed nine whites and injured another six before they were stopped.

| New York Slave Revolt of 1712 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Slave Revolts in North America | |||

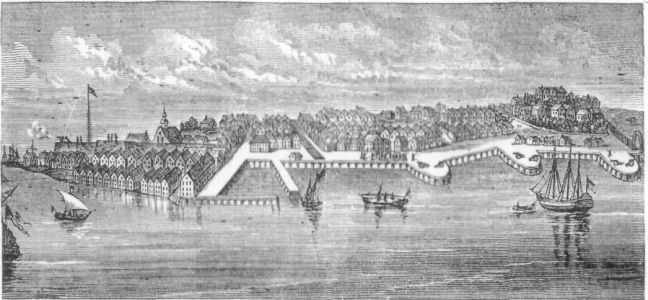

New York's Municipal Slave Market, c. 1730 | |||

| Date | April 6, 1712 | ||

| Location | |||

| Caused by | Slavery, the erosion of the rights of free blacks | ||

| Goals | Emancipation, Liberation | ||

| Methods | Arson, ambush | ||

| Resulted in | Suppression | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

| Casualties and losses | |||

| |||

| Part of a series on |

| North American slave revolts |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

The New York Slave Revolt of 1712 was an uprising in New York City, in the Province of New York, of 23 Black enslaved people. The population consisted of a low 6,000 -8,000 people in which 1,000 of them were slaves. They killed nine whites and injured another six before they were stopped. More than 70 blacks were arrested and jailed. Of these, 27 were put on trial, and 21 convicted and executed.

Although they were certain slaves had different owners it was most common that they still engaged with each other which allowed them to create a plan to rebel. On the night of 6 April 1712, a group of more than twenty slaves, the majority of whom were believed to be Coromantee people of Ghanaian heritage, set fire to a building on Maiden Lane near Broadway to initiate their revolt. Slaves turned the night into a panic. While the local white inhabitants tried to put out the fire, the slaves, armed with guns, hatchets, and swords, fought the whites and then ran off. Eight whites died, and seven were wounded. Over the next few days, colonial forces arrested seventy blacks and jailed them. Twenty-seven were put on trial, 21 of whom were convicted and sentenced to death.[1] Six of them committed suicide even before trial started to avoid pension and consequences such as: physical abusement, excessive work, and unimaginably terrible life conditions that some believe weren't worth going through only to see another day. From then on slaves were seen by European enslavers as a species of property in which they can be owned and ruled by one. They may be seen as individuals who are deprived of rights and justice in such a way where they rarely had any say in most situations. African people were most often captured and enslaved through war, during their childhoods due to being "unwanted" and having no place to be, or even being raided and kidnapped. Many were also were made into from committing crimes, leading them to be punished and put under the "slave" title. Since their rebellion, slavery was mandated for owners to be more harsh on their "property" to create a smaller chance of them to commit these acts once again.

Events

By the early 18th century, New York had one of the largest slave populations of any of the settlements in the Thirteen Colonies. In contrast to the southern states where slaves were primarily agricultural laborers, enslaved people in New York worked in a variety of jobs including as domestic servants, artisans, dock workers, and in various skilled trades.[2] Slaves in New York also lived near each other, making communication easy. Furthermore, they often worked among free black people, a situation that did not exist on most Southern plantations. Slaves in the city could communicate and plan a conspiracy more easily than among those on plantations.[3]

After the seizure of the Dutch colony of New Netherland by the English in 1664 and its incorporation into the Province of New York, the rights of the Free Negro social group were gradually eroded. In 1702, the first of the New York slave codes were passed, which further limited the rights enjoyed by the African community in New York; many of these legal rights, such as the right to own land and marry, were granted during the Dutch colonial period.[4] On December 13, 1711, the New York City Common Council established the city's first slave market near Wall Street for the sale and rental of enslaved Africans and Native Americans.[5][6]

By the early 1700s, about 20 percent of the population were enslaved black people. The colonial government in New York restricted this group through several measures: requiring slaves to carry a pass if traveling more than a mile (1.6 km) from home; discouraging marriage among them; prohibiting gatherings in groups of more than three persons; and requiring them to sit in separate galleries at church services.[7]

A group of more than twenty black slaves, the majority of whom were believed to be Coromantee or Akan,[8] gathered on the night of April 6, 1712, and set fire to a building on Maiden Lane near Broadway.[3] While the white colonists tried to put out the fire, the enslaved blacks, armed with guns, hatchets, and swords, attacked the whites and then ran off. 8 whites were killed and 7 wounded.[9] All of the runaway slaves were captured almost immediately and returned to their owners.[10]

Aftermath

Colonial forces arrested seventy blacks and jailed them. Six are reported to have committed suicide. Twenty-seven were put on trial, 21 of whom were convicted and sentenced to death, including one woman with child.[10] Twenty were burned to death and one was executed on a breaking wheel.[11]

After the revolt, the city and colony passed more restrictive laws governing black and Indian slaves. Slaves were not permitted to gather in groups of more than three, they were not permitted to carry firearms, and gambling was outlawed. Crimes of property damage, rape, and conspiracy to kill qualified for the death penalty. Free blacks were still allowed to own land, however. Anthony Portuguese (alternately spelled Portugies),[4] owned land that makes up a portion of present-day Washington Square Park; this continued to be owned by his daughter and grandchildren.[12]

The colony required slave owners who wanted to free their slaves to pay a tax of £200 per person, then an amount much higher than the cost of a slave. In 1715 Governor Robert Hunter argued in London before the Lords of Trade that manumission and the chance for a slave to inherit part of a master's wealth was important to maintain in New York. He said that this was a proper reward for a slave who had helped a master earn a lifetime's fortune, and that it could keep the slave from descending into despair.[10]

This revolt also played a big part in the New York Conspiracy of 1741. There were numerous poor whites, enslaved people and freedmen that were involved in the Conspiracy of 1741 that had family ties or direct connection to this revolt. One speculation is that "John Provoost [owner of Toby (hanged), juror, and grand juror in 1741] and David Provoost [owner of Lowe (transported) and grand juror in 1741] were probably the nephew and son, respectively, of David Provoost, Jr., a witness in the 1712 trials. David Provoost, Jr., was likely the cousin of Abraham Provoost, whose slave Quacko was burned in 1712" (Plaag 20).[13] Many other families were involved and a lot of other stories align with each others. One thing is for certain, this slave revolt in 1712 had a lasting impact on the enslaved people in New York.

References

- ^ Hughes, Ben (2021). When I Die I Shall Return to My Own Land: The New York Slave Revolt of 1712. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 9781594163562.

- ^ "MAAP – Place Detail: Slave Revolt of 1712". Retrieved November 25, 2016.

- ^ a b "New York's Revolt of 1712". Africans in America. WGBH-TV. Retrieved January 5, 2008.

- ^ a b Christoph, Peter R. (1991). "The Freedmen of New Amsterdam". In McClure Zeller, Nancy Anne (ed.). A Beautiful and fruitful place : selected Rensselaerswijck Seminar papers (PDF). New Netherland Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 6, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2018. View at the HathiTrust Digital Library

- ^ Slave Market. Mapping the African American Past, Columbia University.

- ^ Peter Alan Harper (February 5, 2013). How Slave Labor Made New York. The Root. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ Diehl, Lorraine B. (October 5, 1992). "Skeletons in the Closet". New York Magazine. New York Media, LLC. pp. 78–86. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Hughes, Ben (2021). When I Die I Shall Return to My Own Land: The New York Slave Revolt of 1712. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 9781594163562.

- ^ Hughes, Ben (2021). When I Die I Shall Return to My Own Land: The New York Slave Revolt of 1712. Westholme Publishing. ISBN 9781594163562.

- ^ a b c Hunter, Robert (1712). "New York Slave Revolt 1712". In O’Callaghan, E. B. (ed.). Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York; procured in Holland, England and France. Albany, New York: Weeds, Parson. Archived from the original on June 14, 2016. Retrieved November 25, 2016 – via SlaveRebellion.org.

- ^ Pencak, William (July 15, 2011). Historical Dictionary of Colonial America. Scarecrow Press. p. 161. ISBN 9780810855878. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Geismar, Joan H. (April 2004). "The Reconstruction of the Washington Square Arch and Adjacent Site Work" (PDF). New York City Department of Park and Recreation. p. 10. Retrieved April 4, 2018.

- ^ Flaag, Eric (Summer 2003). "New York's 1741 Slave Conspiracy in a Climate of Fear and Anxiety".

Bibliography

- Berlin, Ira & Harris, Leslie (2005), Slavery in New York, New York: New Press, ISBN 1565849973.

- Horton, James & Horton, Lois (2005), Slavery and the Making of America, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 019517903X.

- Hughes, Ben (2021), When I Die I shall Return to My Own Land: The New York Slave Revolt of 1712, Westholme Publishing, ISBN 9781594163562

- Katz, William Loren (1997), Black Legacy, A History of New York's African Americans, New York: Atheneum, ISBN 0689319134.

- Johnson, Mat (2007), The Great Negro Plot, New York: Bloomsbury, ISBN 9781582340999 (Fiction).

- Hughes, Ben (2024), The New York City Slave Revolt of 1712: The First Enslaved Insurrection in British North America, Westholme Publishing, ISBN 978-1594164163

See also

- ^ "Slavery | Definition, History, & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. September 22, 2025. Retrieved October 21, 2025.