Octavius Valentine Catto (February 22, 1839 – October 10, 1871) was an American educator, intellectual, and civil rights activist. He became principal of male students at the Institute for Colored Youth, where he had also been educated. Born free in Charleston, South Carolina, in a prominent mixed-race family, he moved north as a boy with his family. After completing his education, he went into teaching, and becoming active in civil rights. He also became known as a top cricket and baseball player in 19th-century Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. A Republican, he was shot and killed in election-day violence in Philadelphia, where ethnic Irish of the Democratic Party, who were anti-Reconstruction and had opposed black suffrage, attacked black men to prevent their voting.

Octavius Catto | |

|---|---|

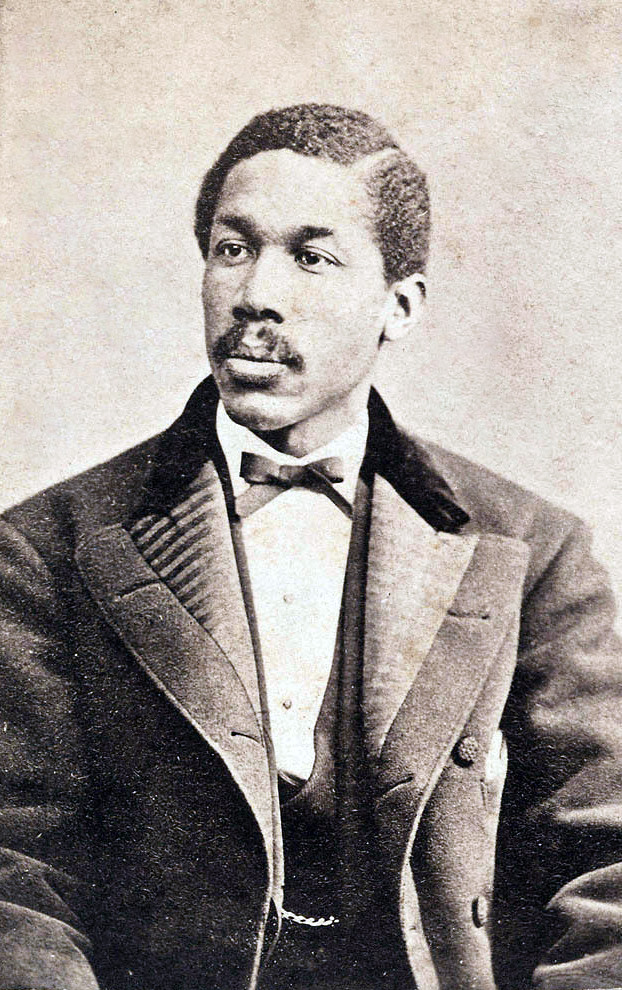

Catto, year unknown | |

| Born | February 22, 1839 |

| Died | October 10, 1871 (aged 32) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US |

| Cause of death | Murder |

| Resting place | Eden Cemetery, Collingdale, Pennsylvania, US |

| Occupations | Educator and civil rights activist |

| Movement | Civil rights movement |

| Partner | Caroline LeCount (fiancée) |

Octavius Valentine Catto (February 22, 1839 – October 10, 1871) was an American educator, intellectual, and civil rights activist. He became principal of male students at the Institute for Colored Youth, where he had also been educated. Born free in Charleston, South Carolina, in a prominent mixed-race family, he moved north as a boy with his family. After completing his education, he went into teaching, and became active in civil rights. He also became known as a top cricket and baseball player in 19th-century Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He helped organize and played for the Philadelphia Pythians baseball team. He was shot and killed on election-day in Philadelphia, where ethnic Irish of the Democratic Party, who were anti-Reconstruction and had opposed black suffrage, attacked black men to prevent their voting.

Early life

Octavius Catto was born free. His mother Sarah Isabella Cain was a free member of the city's prominent mixed-race DeReef family, which had been free for decades and belonged to the Brown Fellowship Society, a mark of their status.[1] His father, William T. Catto, had been an enslaved millwright in South Carolina who gained his freedom. He was ordained as a Presbyterian minister before taking his family north, first to Baltimore, and then to Philadelphia, where they settled in the free state of Pennsylvania. The state had gradually abolished slavery, beginning before the end of the Revolutionary War.[2][3]

William T. Catto was a founding member of Philadelphia's Banneker Institute, an African-American intellectual and literary society.[4] He wrote "A Semi-Centenary Discourse", a history of the First African Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia.[5]

Catto began his education at Vaux Primary School and then Lombard Grammar School, institutions specifically for the education of African-Americans, in Philadelphia. In 1853, he entered the, otherwise, all-white Allentown Academy in Allentown, New Jersey, located across the Delaware River and 40 miles north. In 1854, when his family returned to Philadelphia, he became a student at that city's Institute for Colored Youth (ICY).[1] Managed by the Society of Friends (Quakers), ICY's curriculum included the classical study of Latin, Greek, geometry, and trigonometry.[6]

While a student at ICY, Catto presented papers and took part in scholarly discussions at "a young men's instruction society". Led by fellow ICY student Jacob C. White Jr., they met weekly at the ICY.[1][4] Catto graduated from ICY in 1858, winning praise from principal Ebenezer Bassett for "outstanding scholarly work, great energy, and perseverance in school matters."[1] Catto did a year of post-graduate study, including private tutoring in both Greek and Latin, in Washington, D. C.

Activism and influence

In 1859, he returned to Philadelphia, where he was elected full member and Recording Secretary of the Banneker Institute. He also was hired as teacher of English and mathematics at the ICY.[1][4][7]

On May 10, 1864, Catto delivered ICY's commencement address, which gave a historical synopsis of the school.[6] In addition, Catto's address touched on the issue of the potential lack of sensitivity of white teachers toward the needs and interests of African-American students:

It is at least unjust to allow a blind and ignorant prejudice to so far disregard the choice of parents and the will of the colored tax-payers, as to appoint over colored children white teachers, whose intelligence and success, measured by the fruits of their labors, could neither obtain nor secure for them positions which we know would be more congenial to their tastes.[6]

Catto also spoke of the Civil War, then in progress. He believed that the United States government had to evolve several times in order to change. He understood that the change must come not necessarily for the benefit of African Americans, but more for America's political and industrial welfare. This would be a mutual benefit for all Americans.

... It is for the purpose of promoting, as far as possible, the preparation of the colored man for the assumption of these new relations with intelligence and with the knowledge which promises success, that the Institute feels called upon at this time to act with more energy and on a broader scale than has heretofore been required.[6]

On January 2, 1865, at a gathering at the National Hall in Philadelphia to celebrate the second anniversary of the Emancipation Proclamation, Catto "delivered a very able address, and one that was a credit to the mind and heart of the speaker."[8]

In 1869, Bassett left ICY when he was appointed ambassador to Haiti. Catto lobbied to succeed Bassett as principal; however, the ICY board chose Catto's fellow teacher, Fanny Jackson Coppin, as head of the school. Catto was elected as the principal of the ICY's male department.[1][9] In 1870, Catto joined the Franklin Institute, a center for science and education whose white leaders supported Catto's membership despite his race, in the face of some opposition.[1] Catto served as principal and teacher at ICY until his death in 1871. His successor in the position was Richard Theodore Greener.[10]

Sportsman

Catto was active not just in the public arenas of education and equal rights, but also on the sporting field. Like many other young men of Philadelphia, both white and black, Catto began playing cricket while in school, as it was a British tradition.[1] Later he took up the American sport of baseball. Following the Civil War, he helped establish Philadelphia as a major hub of what became Negro league baseball. Along with Jacob C. White, Jr., he ran the Pythian Base Ball Club of Philadelphia.[1] The Pythians had an undefeated season in 1867.[1]

Following the 1867 season, Catto, with support from players from the white Athletic Base Ball Club, applied for the Pythians' admission into the newly formed Pennsylvania Base Ball Association. As it became clear that they would lose any vote by the Association, they withdrew their application.[1] In 1869, the Pythians challenged various white baseball teams in Philadelphia to games. The Olympic Ball Club accepted the challenge. The first match game between black and white baseball teams took place on September 4, 1869, ending in the Pythians' defeat, 44 to 23. (New York Times, September 5, 1869)

Activist for equal rights

The Civil War increased Catto's activism for abolition and equal rights. He joined with Frederick Douglass and other black leaders to form a Recruitment Committee to sign up black men to fight for the Union and emancipation. After the Confederate invasion of Pennsylvania in 1863, Catto helped raise a company of black volunteers for the state's defense; their help, however, was refused by the staff of Major General Darius N. Couch on the grounds that the men were not authorized to fight. (Couch was later reprimanded by US Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, but not until the aspiring soldiers had returned to Philadelphia.) Acting with Douglass and the Union League, Catto helped raise eleven regiments of United States Colored Troops in the Philadelphia area. These men were sent to the front and many saw action. Catto was commissioned as a major in the army but never saw action.[1]

On Friday, April 21, 1865, at the State House (Independence Hall) in Philadelphia, Catto presented the regimental flag to Lieutenant Colonel Trippe, commander of the 24th United States Colored Troops. An account of Catto's presentation speech was reported the following day in the Christian Recorder:

The speaker then paid a tribute to the two hundred thousand blacks, who, in spite of obloquy and the old bane of prejudice, have been nobly fighting our battles, trusting to a redeemed country for the full recognition of their manhood in the future. He thought that in the plan of reconstruction, the votes of the blacks could not be lightly dispensed with. They were the only unqualified friends of the Union in the South. In the impressive language written on this flag, "Let Soldiers in War be Citizens in Peace," the Banks policy may plant the seed of another revolution. Our statesmen will have to take care lest they prove neither so good nor wise under the seductions of mild-eyed peace, as heretofore, amidst the tumults of grim-visaged war. Merit should also be recognised in the black soldier, and the way opened to his promotion. De Tocqueville prophesied that if ever America underwent Revolution, it would be brought about by the presence of the black race, and that it would result from the inequality of their condition. This has been verified. But there is another side to the picture; and while he thought it his duty to keep these things before the public, there are motives of interest founded on our faith in the nation's honor, to act in this strife. Freedom has rapidly advanced since the firing on Sumter; and since the Genius of Liberty has directed the war, we have gone from victory to victory. Soldiers! Accept this flag on behalf of the citizens of Philadelphia. I know too well the mettle of your pasture, that you will not dishonor it. Keep before your eyes the noble deeds of your fellows at Port Hudson, Fort Wagner, and on other historic fields. Desert them not. Accept, Colonel, this flag on behalf of the regiment, and may God bless you and them.

— Christian Recorder, April 22, 1865

In November 1864, Catto was elected to be the Corresponding Secretary of the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League.[1] He also served as Vice President of the State Convention of Colored People held in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in February 1865. (Liberator March 3, 1865: 35).

Catto fought for the desegregation of Philadelphia's trolley car system, along with his fiancée Caroline LeCount and abolitionist William Still.[11] The May 18, 1865, issue of the New York Times ran a story discussing the civil disobedience tactics employed by Catto as he fought for civil rights:

Philadelphia, Wednesday, May 17—2 P. M.

Last evening a colored man got into a Pine-street passenger car, and refused all entreaties to leave the car, where his presence appeared to be not desired.

The conductor of the car, fearful of being fined for ejecting him, as was done by the Judges of one of our courts in a similar case, ran the car off the track, detached the horses, and left the colored man to occupy the car all by himself.

The colored man still firmly maintains his position in the car, having spent the whole of the night there.

The conductor looks upon the part he enacted in the affair as a splendid piece of strategy.

The matter creates quite a sensation in the neighborhood where the car is standing, and crowds of sympathizers flock around the colored man.

— New York Times, May 18, 1865, p. 5

A meeting of the Union League of Philadelphia was held in Sansom Street Hall on Thursday, June 21, 1866, to protest and denounce the forcible ejection of several black women from Philadelphia's street cars. At this meeting, Catto presented the following resolutions:

Resolved, That we earnestly and unitedly protest against the proscription which excludes us from the city cars, as an outrage against the enlightened civilization of the age.

Resolved, That we cannot discover any reason based upon good sense or common justice for the continuance of a practice which has long ceased to disgrace democratic New York, Washington, St. Louis, Harrisburg and other cities, whose pledges of fidelity to the principles of freedom and civil liberty have not been so frequent as have been those of our own city.

Resolved, That, with feelings of sorrow rather than pride, we remind our white fellow-citizens of the glaring inconsistency and palpable injustice of forcing delicate women and innocent children, by the ruthless hands of ungentlemanly and unprincipled conductors and drivers, to places on the front platform, subjecting to storm and rain, cold and heat, relatives of twelve thousand colored soldiers, whose services these very citizens gladly accepted when the nation was in her hour of trouble, and they seriously entreated, under the chances of IMPARTIAL DRAFTS, to fill the depleted ranks of the Union army.

Resolved, That while men and women of a Christian community can sit unmoved and in silence, and see women barbarously thrown from the cars, – and while our courts of justice fail to grant us redress for acts committed in violation of the chartered privileges of these railroad companies, – we shall never rest at ease, but will agitate and work, by our means and by our influence, in court and out of court, asking aid of the press, calling upon Christians to vindicate their Christianity, and the members of the law to assert the principles of the profession by granting us justice and right, until these invidious and unjust usages shall have ceased.

Resolved, That we do solemnly pledge ourselves to assist by our means any suit brought against the perpetrators of outrages such as those, the occurrence of which has convened this meeting; and we respectfully call upon our liberal-minded and friendly white fellow-citizens to cease to remain silent witnesses of the grievance of which we complain, and to demonstrate the sincerity of their professions by an interference in our behalf. (Brown 1866)

Later enlisting the help of Congressmen Thaddeus Stevens and William D. Kelley, Catto was instrumental in the passage of a Pennsylvania bill that prohibited segregation on transit systems in the state. Publicity about a conductor's being fined who refused to admit Catto's fiancée to a Philadelphia streetcar helped establish the new law in practice.[1]

Catto's crusade for equal rights was capped in March 1869, when Pennsylvania voted to ratify the 15th Amendment, which prohibited discrimination against citizens in registration and voting based on race, color or prior condition; effectively, it provided suffrage to black men. (No women then had the vote.) It was fully ratified in 1870.[citation needed]

Following the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870, Black political organizing in Philadelphia expanded rapidly. Octavius Catto was a leading figure in this movement through his work with the Pennsylvania Equal Rights League (PERL), which coordinated Black civil rights advocacy, voter education, and political mobilization across the state. In April 1870, Catto and other PERL leaders helped organize a massive Fifteenth Amendment celebration parade in Philadelphia[12], in which thousands of Black men marched by ward. Contemporary reporting and later historical analysis describe the parade as a deliberate demonstration of electoral readiness and political discipline, signaling that newly enfranchised Black voters would have a decisive impact on upcoming elections, including the 1871 mayoral race. [13]

Assassination

By 1871, Black voters in Philadelphia overwhelmingly supported the Republican Party, threatening the control of the city’s Democratic political machine. The Democratic administration of Mayor Daniel M. Fox, working through ward organizations, responded with systematic efforts to suppress the Black vote. In the Fourth Ward, political power was controlled by Alderman William “Bull” McMullen, whose organization relied on patronage, police loyalty, and street violence to maintain electoral dominance. Historical research and trial records show that McMullen’s organization coordinated Election Day violence using both uniformed police officers and civilian enforcers.[14]

On Election Day, October 10, 1871, McMullen’s Fourth Ward organization initiated a campaign of racially targeted political violence intended to intimidate Black voters and disrupt polling. Police officers aligned with the Fourth Ward machine illegally separated Black and white voters at polling places, assaulted Black men attempting to vote, and either participated in or enabled armed attacks in surrounding neighborhoods. The violence spread beyond the Fourth Ward into adjacent Black communities. [15][16]

In the hours preceding Catto’s death, multiple Black men were shot or killed within the same area of the city. Within a two-block radius of the site where Catto was later attacked, Jacob Gordon, Levi Bolden, Moses Wright, and Isaac Chase were violently assaulted or killed between the night before and the afternoon of Election Day. Armed groups moved through Black residential streets, breaking into homes, attacking residents, and forcing the closure of polling places. [17][18][19]

According to witness testimony and trial evidence, Frank Kelly, a Democratic partisan operating within McMullen’s Fourth Ward organization, recognized Catto on South Street between Eighth and Ninth Streets. Kelly had already participated in violent attacks earlier that day, including the fatal assault on Isaac Chase. After recognizing Catto, Kelly confronted and shot him multiple times. [20]

Catto did not die immediately. Police testimony indicates that after the first shot, Catto sought protection from nearby officers and requested their assistance. Kelly fired additional shots moments later, resulting in fatal wounds. Kelly fled the scene. He was able to escape Philadelphia and lived for 7 years in Chicago. He was recognized and apprehended, tried, and acquitted. No police officers or political officials were convicted for their roles in the Election Day violence. [20]

Catto's military funeral at Lebanon Cemetery in Passyunk was well-attended. Later, after the cemetery was closed down, Catto's remains were reinterred at Eden Cemetery, in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.[21]

O. V. Catto Memorial

On June 17, 1878, R. W. Wallace, a biographer of Catto, wrote to the Christian Recorder, questioning why no one was taking care of Catto's grave:

Can you inform me through your paper, why there is no care taken of Prof. O. V. Catto's grave? I have recently been down to the Cemetery and was surprised to see its condition. Thousands of people have asked me about the same thing, and, when I am compelled to say there is no sign of any stone to his grave, while both white and colored stand ready to help in the matter, it is not creditable to us. Something ought to be done in the matter. I believe almost everybody would give something toward getting a stone. I am the publisher of his life, and am prepared to speak in regard to the interest taken by all classes of people. (Wallace 1878)

However, Catto's memory continued to be revered in the Black community. His fiance Carolyn LeCount influenced the City of Philadelphia schools to rename the Ohio Street School to the Octavius V. Catto school.[22][23] Fraternal organizations named lodges after him. [24]

Some twenty years later, the New York Times reported:

Many Negro citizens of Philadelphia are now endeavoring to have carried into speedy execution a long-cherished wish to have erected there a monument to Prof. Octavius V. Catto, one of their race, who was killed in an election day riot in that city twenty-six years ago. He was long an instructor in the Institute for Colored Youth, and the plan is to erect a mausoleum, and that the work be done by the pupils of the school as far as possible.

— New York Times, November 12, 1897, p. 6

21st century memorial campaign

An annual remembrance ceremony was initiated in 1995.[25]

On June 14, 2006, the Board of Trustees of the O. V. Catto Memorial announced the kickoff of a $1.5 million fundraising campaign to erect a memorial statue to Catto. The Abraham Lincoln Foundation made the first contribution of $25,000. On October 10, 2007, the 136th anniversary of Catto's death, the Octavius V. Catto Memorial Fund erected a headstone at Catto's burial site at Eden Cemetery in Collingdale, Pennsylvania.[26]

On July 26, 2011, to commemorate his life, the General Meade Society of Philadelphia participated in a wreath-laying ceremony at 6th and Lombard Streets in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The first OV Catto award was presented that year.[citation needed]

To honor the man affectionately called the "19th century Martin Luther King", Mayor Jim Kenney announced on June 10, 2016, that a new sculpture to commemorate Catto and other leaders would be erected outside Philadelphia City Hall.[citation needed]

The sculptural group, A Quest for Parity, including a twelve-foot bronze statue of Catto, was installed at Philadelphia's City Hall on September 24, 2017, and dedicated on September 26, 2017. The sculptor is Branly Cadet. It is the first public monument in Philadelphia to honor a specific African American.[27]

See also

References

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Silcox, Harry C. (1977). "Nineteenth Century Philadelphia Black Militant: Octavius V. Catto (1839–1871)". Pennsylvania History. 44 (1): 53–76. Retrieved September 26, 2023 – via PennState University Libraries.

- ^ Delany, M. R. (1852). The Condition, Elevation, Emigration, and Destiny of the Colored People of the United States. Self-published.

- ^ Douglass, F (October 20, 1848). W. T. Catto, North Star.

- ^ a b c Lapsansky, E. J. (1993). "Discipline to the Mind". Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography. Vol. 117, no. 1/2. Philadelphia's Banneker Institute, 1854–1872. pp. 83–102. Archived from the original on February 13, 2012. Retrieved June 19, 2007.

- ^ Delivered in the First African Presbyterian Church, in Philadelphia, on the fourth Sabbath of May, 1857, with a History of the Church from the first organization, including a brief Notice of Rev. John Gloucester, its First Pastor, Philadelphia: Joseph M. Wilson, 1857,

also, An Appendix, containing Sketches of all the Coloured Churches in Philadelphia

- ^ a b c d Catto, O. V. (May 10, 1864). Our Alma Mater, An Address Delivered at Concert Hall on the Occasion of the Twelfth Annual Commencement of the Institute for Colored Youth. Philadelphia: C. Sherman, Printers.

- ^ Griffin, H. H. (n. d.). The Trial of Frank Kelly, for the Assassination and Murder of Octavius V. Catto, On October 10, 1871. Philadelphia: Daily Tribune Publishing Co. Archived from the original on July 9, 2007.

- ^ Christian Recorder, January 7, 1865

- ^ References to him as an influence on one of his students, Hershel V. Cashin, can be found in the book, Cashin, Sheryll (July 31, 2008). The Agitator's Daughter: A Memoir of Four Generations of One Extraordinary African-American Family. PublicAffairs. ISBN 9780786721726.

- ^ Simmons, William; Turner, Henry McNeal (1887). Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company. pp. 327–335.

- ^ "Caroline LeCount & the Ohio Street School". Biographical Profiles - Explore the story of women's activism through documents & images. October 3, 2020. Retrieved September 28, 2022.

- ^ "Joyous Celebrations of Enfranchisement in the Black Metropolis". The Evening Telegraph. April 26, 1870. p. 8. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ Metropolis, 1838 Black (December 17, 2025). "A Procession of Unified Purpose: The Day the Philadelphia Black Metropolis Announced Its Power". 1838BlackMetropolis. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Silcox, Harry C. (1989). Philadelphia politics from the bottom up : the life of Irishman William McMullen, 1824-1901. Internet Archive. Philadelphia : Balch Institute Press ; London ; Cranbury, NJ : Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0-944190-01-2.

- ^ "Report on Election Violence". The Philadelphia Inquirer. October 11, 1871. p. 2. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ "Interview that includes Jacob C. White after The election day violence". The Philadelphia Inquirer. October 12, 1871. p. 3. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ "Report on Election Violence". The Philadelphia Inquirer. October 11, 1871. p. 2. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ "Election Violence reporting". The Philadelphia Inquirer. October 12, 1871. p. 3. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ Quinones, Michiko (October 9, 2025). "The Forgotten Victims and Organized Violence To Suppress the Black Vote on Election Day 1871". 1838BlackMetropolis. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ a b Griffen, Henry H. (1877). The trial of Frank Kelly for the assassination (!) & murder of Octavius V. Catto, on October 10, 1871 . Philadelphia: Daily Tribune Publishing Company.

- ^ Philadelphia Magazine: Finding African American History at Delaware County’s Eden Cemetery

- ^ Edmunds, Franklin Davenport (1926). The Public School Buildings of the City of Philadelphia ... F.D. Edmunds.

- ^ Quinones, Michiko (May 12, 2024). "A Love Story; How The Institute for Colored Youth Birthed a Philly Public School in 1860". 1838BlackMetropolis. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ "PastPerfect". philadelphiahistory.catalogaccess.com. Retrieved January 3, 2026.

- ^ Andy Waskie (Professor of History, Temple University) (February 15, 2015), "Introductory remarks", Ceremony at 7th and Lombard Streets, Philadelphia, PA

- ^ "Philadelphia civil rights hero to get statue at City Hall". PhillyVoice. June 10, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2022.

- ^ Salisbury, Stephan (September 25, 2017). "A monument at last for Octavius Catto, the activist who changed Philadelphia". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved September 25, 2017.

Bibliography

- Biddle, Daniel R.; Dubin, Murray (2010). Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-466-3. Archived from the original on October 10, 2020. Retrieved October 8, 2020.

- Lane, R. (1991). William Dorsey's Philadelphia and Ours: On the Past and Future of the Black City in America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195065664.

- "Anniversary of the Banneker Institute". Christian Recorder. January 7, 1865.

- "Presentation of Colors to the 24th Regt., U. S. C. T.". Christian Recorder. April 22, 1865.

- Brown, J. W. (June 30, 1868). "Home Affairs: The Cars and Our People". Christian Recorder.

- Wallace, R. W. (June 20, 1878). "Prof. O. V. Catto's Grave". Christian Recorder.

- "Convention of Colored People". Liberator. Vol. 35, no. 9. March 3, 1865. p. 35.

- "The Rights of Colored Citizens: Curious Affair in Philadelphia". New York Times. May 18, 1865. p. 5.

- "Base Ball". New York Times. September 5, 1869. p. 1.

- "New York Times". November 12, 1897. p. 6.

- Waskie, A. (n. d.) (July 3, 2017). Biography of Octavius V. Catto – Forgotten Black Hero of Philadelphia.

Further reading

- "The Forgotten Hero". National Public Radio.

- "Octavius V. Catto, 1839–1871". Research Resources in Philadelphia Collections. Philadelphia Area Consortium of Special Collections Libraries. Archived from the original on November 17, 2013. Retrieved November 1, 2013.

- Biddle, Daniel R.; Dubin, Murray (August 13, 2010). Tasting Freedom: Octavius Catto and the Battle for Equality in Civil War America. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1592134656.

- "Forging Citizenship and Opportunity - O.V. Catto's Legacy and America's Civil Rights History". Archived from the original on July 26, 2025. Retrieved January 27, 2019.

External links

Media related to Octavius Catto at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Octavius Catto at Wikimedia Commons