Negrito skull confirms Taiwan indigenous legends of ‘little Black people’

6,000-year-old skull found in Taitung cave was that of a woman who was 139 cm tall

TAIPEI (Taiwan News) — The discovery of a 6,000-year-old skull of a Negrito woman confirms legends by almost all of Taiwan’s Indigenous tribes of “little Black people” that span centuries.

On Oct. 4, a journal article article was published in World Archeology titled “Negritos in Taiwan and the wider prehistory of Southeast Asia: new discovery from the Xiaoma Caves.” The authors of the study report that cranial morphometric studies of a skeleton found in the Xiaoma Caves in Taitung County’s Chenggong Township “for the first time, validates the prior existence of small stature hunter-gatherers 6,000 years ago.”

With the exception of the Yami (Tao) people on Orchid Island, Taiwan’s 15 other indigenous peoples have legends about “little Black people” who were short in stature, with dark skin, and frizzy hair who lived in remote mountain areas. Some 258 accounts of these peoples by Indigenous tribes have been recorded by researchers in the Qing Dynasty, the Japanese colonial period, and since 1945.

Qing Dynasty records state that these dark-skinned peoples spoke languages that were different from the Austronesians. The Saisiyat have legends of extensive contact with the “Black pygmy people,” who they called the Ta’ai.

Saisiyat say they learned much in the way of medicine, singing, dancing, and other rituals from the Ta’ai. However, because they claimed that Ta’ai often harassed their women, so the Saisiyat killed most of them by laying a trap.

They soon came to regret this act because the tribe suffered many misfortunes afterward and it was two surviving elder Ta’ai members who taught the Saisiyat the Pas-ta’ai ritual. This ritual has since been performed every two years for many centuries, with a grand ceremony practiced once every 10 years.

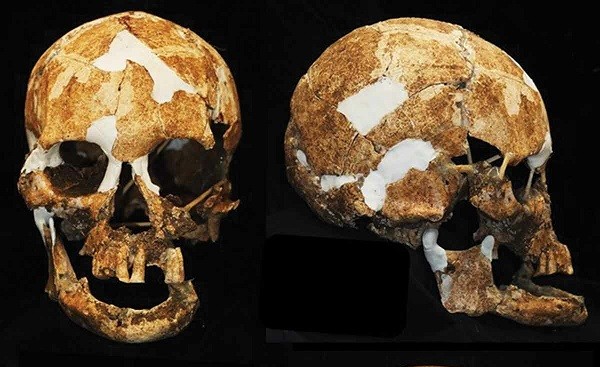

Cranial profile of the Xiaoma female. (Hirofumi Matsumura photo)

Scientists found the skull was that of a female and her cranial features and size were closest to Philippine Negritos and the people of India’s Andaman Islands. This population is believed to be tied to the “first layer” of anatomically modern humans (AMH) who show a closer resemblance to Africans than present-day Eurasians, who represent the “second-layer.”

The “Out of Africa” theory posits that Negrito groups in the Andaman Islands, Malay Peninsula, and Philippines are descended from some of the earliest groups of AMH who are believed to have traveled by land from Africa, through the Arabian Peninsula, South Asia, Southeast Asia, and Australia. It is not yet certain whether their short stature comes from common ancestry or developed later in different areas.

Although archeologists did not find a full skeleton, they estimate the woman was 139 centimeters tall. Researchers are not yet certain whether this group of people was already short in stature before they came to Taiwan or later developed that trait.

It is also uncertain where this group of people came from before arriving in Taiwan. Possible locations mentioned are the Philippines, Borneo, or elsewhere in Mainland Asia.

A few hundred years after what they are calling the “Xiaoma lady” lived in Taiwan, a wave of Neolithic farmers with different features began to stream into Taiwan in 4,800 BC and began to inhabit areas near Xiaoma. The researchers believe that these Neolithic farmers, who formed much larger communities may have driven the Negritos into “refuge” zones such as remote mountain areas.

The authors of the study suggested that this increasing isolation or linguistic differences with the Austronesian peoples could have led to the decline and disappearance of the Negritos in Taiwan.

https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/4680037

Pas-ta'ai (Chinese: 矮靈祭; pinyin: Ǎilíngjì), the "Ritual to the Spirits of the Short [People]", is a ritual of the Saisiyat people, a Taiwanese aboriginal group. The ritual commemorates the Ta'ai, a tribe of short dark-skinned people they say used to live near them. The ritual is held every two years and all Saisiyat are expected to participate.

History

The Pas-ta'ai ritual is purported to have been practiced for 400 years and was initially practiced every year during the harvest season. It was first recorded in 1915 in the Surveys of the Customs of Barbarian Tribes by researchers operating under the colonial Japanese government. Under Japanese rule, the frequency was reduced to once every two years. According to anthropologist and filmmaker Hu Tai-li, from the Institute of Ethnology at Academia Sinica, the tradition had died down to the point to where it was largely only the elders of the Saisiyat who could practice the rituals; over the last 20 years, however, the tradition has been revitalized in the scope of the larger Aboriginal Taiwanese movement as well as through increasing outsider interest.[1] The Pas-ta'ai ceremonies were officially designated as Taiwan's Cultural Heritage in 2009 and 2010 respectively. Over the years, certain external forces have had negative repercussions on the ritual, including improper intervention on the part of government administrative sectors, biased media coverage, improper tourist behaviour, and the proliferation of waste.

Legend

There are slightly different versions of the myth surrounding the ritual. According to one legend of the Saisiyat, the short people, who were dark-skinned, less than a meter high and lived on the other side of the river, excelled in singing and dancing and were invited to the harvest festivals of the Saisiyat, engaging in a long-standing mutually beneficial relationship. The short people, however, were lascivious and often made advances towards the Saisiyat women. One day, some young Saisiyat decided to take revenge because of this disrespectful act. They cut the sturdy tree on which the short people rested. All the short people, except for two elders, fell from the cliff and died. These two surviving elders taught the Saisiyat the songs and dances of the Pas-ta'ai ritual and then left for the east. Shortly afterwards, the Saisiyat suffered from famine, which they attributed to the vengeful pygmy spirits. In order to appease the spirits, the Saisiyat began to hold the Pas-ta'ai and beg for forgiveness. In addition, the Saisiyat were to be hardworking, fair, honest, and tolerant in dealing with others.[2]

In another version, the two elders of the short people put a curse on the Saisiyat, who pleaded for forgiveness. The elders allowed this on the condition that the Saisiyat practice the dances of the short people to appease the spirits of the dead, else the crops of the Saisiyat would fail and wither.[1]

According to the legends, the short people had magical skills and brought luck to the Saisiyat if treated with respect or handled well.[2]

Ceremony

The ceremony is traditionally the responsibility of the Saisiyat Titiyon family. The ceremony is held in Shiangtian Lake, Donghe Village, Nanzhuang Township (the southern ceremonial group) and in Taai Village, Wufeng Township (the northern ceremonial group). The ritual is held over the course of three days and nights, during the full moon of the 10th lunar month (mid-October), and occurs biannually - the first ritual held in a 10-year period is larger and carries more significance.[2][3] The southern ceremony takes place one day earlier than its northern counterpart, and the two slightly differ in detail. One or two months before the ritual, both ceremonial groups send their delegates to decide on an appropriate date to hold the ritual, which is around the fifteenth day of the tenth month in the lunar calendar. Preparations are then begun and ceremonial songs, forbidden on other occasions, are practiced. The rituals, dances and songs performed in the Pas-ta'ai are complex, consisting of the five phases of raraol (welcoming the spirits), kisirinaolan (treating the spirits), kisitomal (entertaining the spirits), papatnawasak (chasing the spirits) and papaosa (sending off the spirits). Following the five phases is the "post-ritual ceremony," which brings the ceremony to an end.[2]

Traditional costumes with ornate decorations and bells (which enable a connection to the spirit world) are worn for the ceremony. Silvergrass is used to provide spiritual security and to ward off evil. Tribal taboos are carefully observed during the ceremony; Saisiyat tradition holds that those who misbehave during the ceremony will consequently suffer from ill events.[1]

Origins

The description of the Little People as dark-skinned and pygmy-like in stature has led to theories and associations with the Negritos of Southeast Asia. There is currently no scholarly consensus on whether the Little People were of pre-Austronesian origin if they existed at all. Some anthropologists suggest these may have been Proto-Australoid people who possibly arrived from Africa during the early Southern Dispersal 60,000 years ago.[4] The Tsou, Bunun, and Paiwan peoples of Taiwan (amongst others) also hold oral traditions of the existence of similar pygmy-like short peoples who possess similar anthropometric traits with Negritos, possibly suggesting widespread Negrito presence on Taiwan prior to the Austronesian migration, though no physical evidence had been found that attests to their existence, until 2022.[5] A 2019 genetic study comparing the genetic markers of Philippine Negritos with that of several indigenous Taiwanese peoples was inconclusive in its findings; "The deep coalescence of B4b1a2 in the Philippine Negritos, Saisiyat, Atayal, Island Southeast Asia, and SEA (Southeast Asia) suggested a deeply rooted common ancestry, but could not support a past Negrito presence in Taiwan. Conversely, the sharing of cultural components and mtDNa haplogroup D6a2 in Saisiyat, Atayal and Philippine Negritos may characterize a Negrito signature in Taiwan. Although the molecular variation of D6a2 determines its presence in Taiwan back to middle Neolithic, other markers, Y-SNP haplogroups C-M146 and K-M9, warrant further analysis."[4]

Anthropologist Gregory Forth proposes that a common origin lies between the Taiwanese traditions and similar Malayo-Polynesian accounts of little people.[6]

Other theories purport that the "Little People" could be African slaves brought by European merchants during the 1600s. Letters sent by Dutch traders visiting Taiwan in the 1600s mention the existence of "short people" on the island.[1]

See also

Further reading

- Xiuche Lin (2000). History of Taiwan's Aborigines: The Saisiyat. Nantou City: Historical Records Committee of Taiwan Province.

- Yuan-Yi Huang (2008). When "Ta'ay" is Confronted with "Journalists": A Study of tourism and news coverage of the Pas-ta'ai. Master's Thesis, Graduate Institute of Journalism, National Taiwan University.

- Provisional Committee on the Investigation of Taiwan Old Customs, Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan. Translated by the Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica (1998). Surveys of the Customs of Barbarian Tribes, Third Volume, The Saisiyat. Taipei: Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica.

- Bin-Xiong Liu and Tai-Li Hu (1987). A Study of the Traditional Ceremonies, Songs and Dances of Taiwan's Aborigines. Nantou County: Department of Household Registration, Government of Taiwan Province.

References

- ^ a b c d Gluck, Caroline (7 December 2006). "Taiwan aborigines keep rituals alive". BBC News. BBC. Archived from the original on 2019-11-03. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ a b c d "A Past that Has Witnessed Gratitude and Resentment: The Legend of the Pas-ta'ai". culture.teldap.tw. Retrieved 2019-04-29.

- ^ "Saisiyat tribe". Shung Ye Museum of Formosan Aborigines. Archived from the original on 23 February 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ a b Lan-Rong Chen; Jean Alain Trejaut; Ying-Hui Lai; Zong-Sian Chen; Jin-Yuan Huang; Marie Lin; Jun-Hun Loo (October 2019). "Mitochondrial DNA Polymorphisms of the Saisiyat Indigenous Group of Taiwan, Search for a Negrito Signature". Edelweiss Journal of Biomedical Research and Review. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

- ^ https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/news/4680037

- ^ Forth, Gregory (Jan 26, 2009). Images of the Wildman in Southeast Asia: An Anthropological Perspective. New York: Routledge. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-7103-1354-6. Retrieved 6 October 2020.

External links