The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between various groups of Native Americans and Black Indians collectively known as Seminoles and the United States, part of a series of conflicts called the Seminole Wars. The Second Seminole War, often referred to as the Seminole War, is regarded as “the longest and most costly of the Indian conflicts of the United States”.

| Second Seminole War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Seminole Wars and Indian removal | |||||||

Rampage during the Second Seminole War. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

Creek (1836–37) | Seminole | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Over 9,000 in 1837[5] cumulative 10,169 regulars, 30,000 militia and volunteers[6] 776 Creeks[7] | 900–1,400 warriors in 1835,[8] fewer than 100 in 1842[9] 6,000 up to 10,000 total population in 1835 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,600 regular troops, unknown militia and civilian[10] | 3,000[11][12] | ||||||

The Second Seminole War, also known as the Florida War, was a conflict from 1835 to 1842 in Florida between the United States and groups of people collectively known as Seminoles, consisting of Creek and Black Seminoles as well as other allied tribes (see below). It was part of a series of conflicts called the Seminole Wars. The Second Seminole War, often referred to as the Seminole War, is regarded as "the longest and most costly of the Indian conflicts of the United States".[13] After the Treaty of Payne's Landing in 1832 that called for the Seminoles' removal from Florida, tensions rose until fierce hostilities occurred in Dade's massacre in 1835. This engagement officially started the war although there were a series of incidents leading up to the Dade battle. The Seminoles and the U.S. forces engaged in mostly small engagements for more than six years. By 1842, only a few hundred native peoples remained in Florida. Although no peace treaty was ever signed, the war was declared over on August 14, 1842, by Colonel William Jenkins Worth.[14]

Background

Bands from various tribes in the southeastern United States had moved into the unoccupied lands in Florida in the 18th century. These included Alabamas, Choctaw, Yamasees, Yuchis and Muscogees (then called "Creeks"). The Muscogees were the largest group, and included people from the Lower Towns and Upper Towns of the Muscogee Confederacy, and both Hitchiti and Muscogee speakers. One group of Hitchiti speakers, the Mikasuki, settled around what is now Lake Miccosukee near Tallahassee. Another group of Hitchiti speakers settled around the Alachua Prairie in what is now Alachua County (see Ahaya). The Spanish in St. Augustine began calling the Alachua Muscogees cimarrones, which roughly meant "wild ones" or "runaways",[a] and which is the probable origin of "Seminole". This name was eventually also applied to the other groups in Florida, although the Native Americans still regarded themselves as members of different tribes. Other groups in Florida at the time of the Seminole Wars included "Spanish Indians", so called because it was believed that they were descended from Calusas, and "rancho Indians", persons of Native American ancestry, possibly both Calusa and Muscogee, and mixed Native American/Spanish ancestry, living at Spanish/Cuban fishing ranchos on the Florida coast.[16] For a brief period after the start of the war, these rancho Indians, particularly those residing along Tampa Bay, were offered protection. However, they were also eventually forced onto reservations.[17]

The United States and Spain were at odds over Florida after the Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolutionary War and returned East and West Florida to Spanish control. The United States disputed the boundaries of West Florida. They accused the Spanish authorities of harboring fugitive slaves (see the Negro Fort) and of failing to restrain the Native Americans living in Florida from raiding the United States. Starting in 1810, the United States occupied and annexed parts of West Florida. Also, the Patriot War of 1812 was part of these ongoing conflicts. In 1818, Andrew Jackson led an invasion of Spanish Florida, during the War of 1812 and the Creek War leading to the First Seminole War.[18]

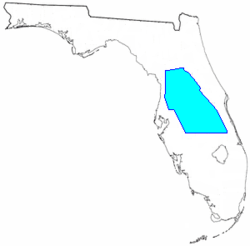

The United States acquired Florida from Spain through the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819 and took possession of the territory in 1821. Now that Florida belonged to the United States, settlers pressured the government to remove the Seminole and their allies altogether. In 1823 the government negotiated the Treaty of Moultrie Creek with the Seminoles, establishing a reservation for them in the middle of the territory. Six chiefs, however, were allowed to keep their villages along the Apalachicola River (see Neamathla).[19]

Move to the reservation

The Seminoles gave up their lands in the panhandle and slowly settled into the reservation, although they occasionally had clashes with European Americans. Colonel (later General) Duncan Lamont Clinch was placed in charge of the Army units in Florida. Fort King was built near the reservation agency, at the site of present-day Ocala, Florida.[20]

By early 1827, the Army reported that the Seminoles were on the reservation and Florida was peaceful. This peace lasted for five years, during which time there were repeated calls for the Seminoles to be sent west of the Mississippi. The Seminoles were opposed to the move, and especially to the suggestion that they should be placed on the Creek reservation. Most European Americans regarded the Seminoles as simply Creeks who had recently moved to Florida, while the Seminoles claimed Florida as their home and denied that they had any connection with the Creeks.[21]

The status of runaway slaves was a continuing irritation between Seminoles and European Americans. "The major problem was not with them [Seminoles] but with the Indian-Negros."[22] General Taylor would not, being a slave holder himself, deny "the Seminoles of their Negros", and "in practice", handed his captives over to Lt. J. G. Reynolds, U.S. Marine Corps, "in charge of immigration."[22] Spain had given freedom to slaves who escaped to Florida under their rule, although the U.S. did not recognize it. Over the years, those who became known as Black or Negro Seminoles established communities separate from the Seminole villages, and the two peoples had close alliances although they maintained separate cultures. "Negroes among the Seminoles constituted a threat to the institution of slavery north of the Spanish border.[23] Slave holders in Mississippi and other border areas were aware of this and "constantly accused the Indians of stealing their Negroes. However, this "accusation" was often reversed; whites were raiding Florida and forcibly stealing the red men's slaves.[23]

Worried about the possibility of an Indian uprising and/or an armed slave rebellion, Governor DuVal requested additional Federal troops for Florida. Instead, Fort King was closed in 1828. The Seminoles, short of food and finding the hunting becoming poorer on the reservation, were wandering off of it more often. Also in 1828, Andrew Jackson, the old enemy of the Seminoles, was elected President of the United States. In 1830 Congress passed the Indian Removal Act. They wanted to solve the problems with the Seminoles by moving them to west of the Mississippi River.[24]

Treaty of Payne's Landing

In the spring of 1832, the Seminoles on the reservation were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the Oklawaha River. The treaty negotiated there called for the Seminoles to move west, if the land was found to be suitable. They were to be settled on the Creek reservation and become part of the Creek tribe. The delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did not leave Florida until October 1832. After the chiefs had toured the area for several months and had conferred with the Creeks who had already been settled there, on March 28, 1833, the federal government produced a treaty with the chiefs' signatures.[25]

Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or that they had been forced to sign it. They said they did not have the power to decide for all the tribes and bands that resided on the reservation. Even some U.S. Army officers claimed that the chiefs had been "wheedled and bullied into signing." Others noted "there is evidence of trickery by the whites in the way the treaty is phrased."[26] The members of the villages in the area of the Apalachicola River were more easily persuaded, however, as they suffered more encroachment from European Americans; they went west in 1834.[25]

The United States Senate finally ratified the Treaty of Payne's Landing in April 1834. The treaty had given the Seminoles three years to move west of the Mississippi. The government interpreted the three years as starting 1832, and expected the Seminoles to move in 1835. Fort King was reopened in 1834. A new Seminole agent, Wiley Thompson, had been appointed in 1834, and the task of persuading the Seminoles to move fell to him. He called the chiefs together at Fort King in October 1834 to talk to them about the removal to the west. The Seminoles informed Thompson that they had no intention of moving, and that they did not feel bound by the Treaty of Payne's Landing. Thompson requested reinforcements for Fort King and Fort Brooke, reporting that, "the Indians after they had received the Annuity, purchased an unusually large quantity of Powder & Lead." General Clinch also warned Washington that the Seminoles did not intend to move, and that more troops would be needed to force them to move. In March 1835 Thompson called the chiefs together to read a letter from President Andrew Jackson to them. In his letter, Jackson said, "Should you... refuse to move, I have then directed the Commanding officer to remove you by force." The chiefs asked for thirty days to respond. A month later the Seminole chiefs told Thompson that they would not move west. Thompson and the chiefs began arguing, and General Clinch had to intervene to prevent bloodshed. Eventually, eight of the chiefs agreed to move west, but asked to delay the move until the end of the year, and Thompson and Clinch agreed.[27]

Five of the most important Seminole chiefs, including Micanopy of the Alachua Seminoles, had not agreed to the move. In retaliation, Thompson declared that those chiefs were removed from their positions. As relations with the Seminoles deteriorated, Thompson forbade the sale of guns and ammunition to them. Osceola, a young warrior beginning to be noticed by the European Americans, was particularly upset by the ban, feeling that it equated Seminoles with slaves and said, "The white man shall not make me black. I will make the white man red with blood; and then blacken him in the sun and rain ... and the buzzard live upon his flesh." In spite of this, Thompson considered Osceola to be a friend, and gave him a rifle. Later, though, when Osceola was causing trouble, Thompson had him locked up at Fort King for a night. The next day, in order to secure his release, Osceola agreed to abide by the Treaty of Payne's Landing and to bring his followers in.[28]

The situation grew worse. A group of European Americans assaulted some Indians sitting around a campfire. Two more Indians came up during the assault and opened fire on the European Americans. Three European Americans were wounded, and one Indian was killed and one wounded. In August 1835, Private Kinsley Dalton (for whom Dalton, Georgia, is named) was killed by Seminoles as he was carrying the mail from Fort Brooke to Fort King. In November, Chief Charley Emathla, wanting no part of a war, led his people to Fort Brooke, where they were to board ships to go west. This was considered a betrayal by other Seminoles. Osceola met Charley Emathla on the trail to Fort King and killed him.[29]

The Dade Battle

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the War Department for the loan of 500 muskets. Five hundred volunteers were mobilized under Brig. Gen. Richard K. Call. Indian war parties raided farms and settlements, and families fled to forts, large towns, or out of the territory altogether. A war party led by Osceola captured a Florida militia supply train, killing eight of its guards and wounding six others. Most of the goods taken were recovered by the militia in another fight a few days later. Sugar plantations along the Atlantic coast south of St. Augustine were destroyed, with many of the slaves on the plantations joining the Seminoles.[30]

The U.S. Army had 11 companies, about 550 soldiers, stationed in Florida. Fort King had only one company of soldiers, and it was feared that they might be overrun by the Seminoles. There were three companies at Fort Brooke, with another two expected on the way, so it was decided to send two companies to Fort King. On December 23, 1835, the two companies, totaling 110 men, left Fort Brooke under the command of Maj. Francis L. Dade. Seminoles shadowed the marching soldiers for five days. On December 28 the Seminoles ambushed the soldiers, and killed all but three of the command, which became known as the Dade Massacre. Only three white men survived the battle. Pvt Edwin DeCourcey was hunted down and killed by a Seminole the next day. The other two survivors, Pvt Ransom Clarke and Pvt Joseph Sprague, returned to Fort Brooke. Only Clarke, who ultimately succumbed to his wounds 5 years later, dying on November 18, 1840, at the age of 28, left any account of the battle from the Army's perspective. Entitled "The Surprising Adventures of Ransom Clark, Among the Indians in Florida", it was published in 1839 by J. Orlando Orton and "printed by Johnson and Marble in Binghamton, New York."[31][b] Joseph Sprague suffered a "shattered arm",[32] served in the army until March 1843, and lived out his days near White Springs, Florida, until possibly 1848. No written material from Sprague's personal military experience's has ever surfaced.[32] The Seminoles lost three men killed, with five wounded. On the same day as the Dade Massacre, Osceola and his followers shot and killed Wiley Thompson and six others outside of Fort King.[33]

In February, Major Ethan Allen Hitchcock was among those who found the remains of the Dade party. In his journal he wrote about the discovery and vented his bitter discontent with the conflict:

The government is in the wrong, and this is the chief cause of the persevering opposition of the Indians, who have nobly defended their country against our attempt to enforce a fraudulent treaty. The natives used every means to avoid a war, but were forced into it by the tyranny of our government.[34]

On December 29, General Clinch left Fort Drane (recently established on Clinch's plantation, about twenty miles (32 km) northwest of Fort King) with 750 soldiers, including 500 volunteers on an enlistment due to end January 1, 1836. They were going to a Seminole stronghold called the Cove of the Withlacoochee, an area of many lakes on the southwest side of the Withlacoochee River. When they reached the river, they could not find the ford, and Clinch had his regular troops ferried across the river in a single canoe they had found. Once they were across and had relaxed, the Seminoles attacked. The troops survived only by fixing bayonets and charging the Seminoles, at the cost of four dead and 59 wounded. The militia provided cover as the Army troops withdrew across the river.[35]

On January 6, 1836, a band of Seminoles attacked the coontie plantation of William Cooley on the New River (in present-day Fort Lauderdale, Florida), killing his wife and children and the children's tutor. The other residents of the New River area and of the Biscayne Bay country to the south fled to Key West.[36] On January 17, volunteers and Seminoles met south of St. Augustine at the Battle of Dunlawton. The volunteers lost four men, with thirteen wounded.[37] On January 19, 1836, the Navy sloop-of-war Vandalia was dispatched to Tampa Bay from Pensacola. On the same day 57 U.S. Marines were dispatched from Key West to help man Fort Brooke.[38]

General Gaines' expedition

The regular American army was very small at the time, with fewer than 7,500 men manning a total of 53 posts.[39] It was spread thin, with the Canada–U.S. border to guard, coastal fortifications to man, and especially, Indians to move west and then watch and keep separated from white settlers. Temporary needs for additional troops were filled by state and territory militias, and by self-organized volunteer units. As news and rumors of the fighting spread, action was taken on many levels. Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott was placed in charge of the war. Congress appropriated US$620,000 for the war. Volunteer companies began forming in Alabama, Georgia and South Carolina. General Edmund P. Gaines put together a force of 1,100 regulars and volunteers in New Orleans and sailed with them to Fort Brooke.[40] A lack of arms was also an issue, with only two arsenals located in Florida, one at Fort Brooke and the other at Fort Marion, with a third under construction in what is now Chattahoochee.[41]

When Gaines reached Fort Brooke, he found it low on supplies. Believing that General Scott had sent supplies to Fort King, Gaines led his men on to Fort King. Along the road they found the site of the Dade Massacre, and buried the bodies in three mass graves. The force reached Fort King after nine days, only to find it was very short on supplies. After receiving seven days' worth of rations from General Clinch at Fort Drane, Gaines headed back for Fort Brooke. Hoping to accomplish something for his efforts, Gaines took his men on a different route back to Fort Brooke, intending to engage the Seminoles in their stronghold in the Cove of the Withlacoochee River. Due to a lack of knowledge of the country, the Gaines party reached the same point on the Withlacoochee where Clinch had met the Seminoles one-and-a-half months earlier, and it took another day to find the ford while the two sides exchanged gunfire across the river.[42]

When a crossing was attempted at the ford of the Withlacoochee, Lt. James Izard was wounded (and later died), and General Gaines was stuck by a bullet. Unable to ford the river, and not having enough ration to return to Fort King, Gaines and his men constructed a fortification, called Camp Izard, and sent word to General Clinch. Gaines hoped that the Seminoles would concentrate around Camp Izard, and that Clinch's forces could then hit the Seminoles in their flank, crushing them between the two forces. General Scott, however, who was in charge of the war, ordered Clinch to stay at Fort Drane. Gaines's men were soon reduced to eating their horses and mules, and an occasional dog, while a battle went on for eight days. Still at Fort Drane, Clinch requested that General Scott change his orders and allow him to go to Gaines' aid. Clinch finally decided to disobey Scott and left to join Gaines just one day before Scott's permission to do so arrived at Fort Drane. Clinch and his men reached Camp Izard on March 6, chasing away the Seminoles.[43]

General Scott's campaign

General Scott had begun assembling men and supplies for a grand campaign against the Seminoles. Three columns, totaling 5,000 men, were to converge on the Cove of the Withlacoochee, trapping the Seminoles with a force large enough to defeat them. Scott would accompany one column, under the command of General Clinch, moving south from Fort Drane. A second column, under Brig. Gen. Abraham Eustis, would travel southwest from Volusia, a town on the St. Johns River. The third wing, under the command of Col. William Lindsay, would move north from Fort Brooke. The plan was for the three columns to arrive at the Cove simultaneously so as to prevent the Seminoles from escaping. Eustis and Lindsay were supposed to be in place on March 25, so that Clinch's column could drive the Seminoles into them.[44]

On the way from St. Augustine to Volusia to take up his starting position, Gen. Eustis found Pilaklikaha, or Palatlakaha (Palatka, Florida), also known as Abraham's Town. Abraham had been a member of the Corps of Colonial Marines and was present at, and taken into custody, at the Battle of Negro Fort. In custody only a short time, he was a Black Seminole leader, and interpreter for the Seminoles, who played a critical role during the Second Seminole War.[45]: 51 Eustis burned the town before moving on to Volusia.

All three columns were delayed. Eustis was two days late departing Volusia because of an attack by the Seminoles. Clinch's and Lindsay's columns only reached their positions on March 28. Because of problems crossing through uncharted territory, Eustis's column did not arrive until March 30. Clinch crossed the Withlacoochee on March 29 to attack the Seminoles in the Cove, but found the villages deserted. Eustis's column did fight a skirmish with some Seminoles before reaching its assigned position, but the whole action had killed or captured only a few Seminoles. On March 31 all three commanders, running low on supplies, headed for Fort Brooke. The failure of the expedition to effectively engage the Seminoles was seen as a defeat, and was blamed on insufficient time for planning and an inhospitable climate.[46]

The Army retreats, Governor Call tries his hand

April 1836 did not go well for the Army. Seminoles attacked a number of forts, including Camp Cooper in the Cove, Fort Alabama on the Hillsborough River north of Fort Brooke, Fort Barnwell near Volusia, and Fort Drane itself. The Seminoles also burned the sugar works on Clinch's plantation. After that, Clinch resigned his commission and left the territory. Fort Alabama was abandoned in late April. In late May, Fort King was also abandoned. In June the soldiers in a blockhouse on the Withlacoochee were rescued after being besieged by the Seminoles for 48 days. On July 23, 1836, Seminoles attacked the Cape Florida lighthouse, severely wounding the assistant keeper in charge, killing his assistant, and burning the lighthouse. The lighthouse was not repaired until 1846. Fort Drane and Fort Defiance successfully drove Seminoles away in early June, each using a single artillery piece in support of troops charging Seminoles.[47]

The Army was suffering terribly from illness; at the time summer in Florida was called the "sickly season". On July 14, Fort Drane was abandoned because of illness, with five out of seven officers and 140 men on the sick list. Troops and supplies from the abandoned fort were sent to Fort Defiance, less than 10 miles (16 km) away. Seminoles attacked the convoy before it could reach Fort Defiance, and the convoy was only able to reach its goal after troops from Fort Defiance arrived to support them. By the end of August, Fort Defiance, on the edge of the Alachua Prairie, was also abandoned. Seeing that the war promised to be long and expensive, Congress appropriated another US$1.5 million, and allowed volunteers to enlist for up to a year.[48][49]

Richard Keith Call, who had led the Florida volunteers as a Brig. Gen. when Clinch marched on the Cove of the Withlacoochee in December 1835, had been appointed Governor of the Territory of Florida on March 16, 1836. Governor Call proposed a summer campaign using militia and volunteers instead of regular Army troops. The War Department agreed to this proposal, but delays in preparations meant the campaign did not start until the end of September. Call also intended to attack the Cove of the Withlacoochee. He sent most of his supplies down the west coast of the peninsula and up the Withlacoochee to set up a supply base. With the main body of his men he marched to the now abandoned Fort Drane, and then on to the Withlacoochee, which they reached on October 13. The Withlacoochee was flooding and could not be forded. The army could not make rafts for a crossing because they had not brought any axes with them. In addition, Seminoles on the other side of the river were shooting at any soldier who showed himself along the river. Call then turned west along the north bank of the river to reach the supply depot. However, the steamer bringing the supplies had sunk in the lower part of the river, and the supply depot was far downstream from where Call was expecting it. Out of food, Call led his men back to Fort Drane, another failed expedition against the Cove.[50]

In mid-November Call tried again. His forces made it across the Withlacoochee this time, but found the Cove abandoned. Call divided his forces, and proceeded south along the river. On November 17, Seminoles were routed from a large camp. There was another battle the next day, and the Seminoles were assumed to be headed for the Wahoo Swamp. Call waited to bring the other column across the river, then entered the Wahoo Swamp on November 21. The Seminoles resisted the advance in the Battle of Wahoo Swamp, as their families were close by, but had to retreat across a stream. Major David Moniac, who was part Creek and possibly the first Native American to graduate from West Point, tried to determine how deep the stream was, but was shot and killed by the Seminoles.[51]

Faced with trying to cross a stream of unknown depth under hostile fire, and with supplies again running short, Call withdrew and led his men to Volusia. On December 9, Call was relieved of command and replaced by Maj. Gen. Thomas Jesup, who took the troops back to Fort Brooke. The enlistments of the volunteers were up at the end of December and they went home.[52]

Jesup takes command

In 1836, the U.S. Army had just four Major Generals. Alexander Macomb, Jr. was the commanding general of the Army. Edmund Gaines and Winfield Scott had each taken to the field and failed to defeat the Seminoles. Thomas Jesup was the last Major General available. Jesup had just suppressed an uprising by the Creeks of western Georgia and eastern Alabama (the Creek War of 1836), upstaging Winfield Scott in the process. Jesup brought a new approach to the war. Instead of sending large columns out to try to force the Seminoles into a set-piece battle, he concentrated on wearing the Seminoles down. This required a large military presence in Florida, and Jesup eventually had a force of more than 9,000 men under his command. About half of the force were volunteers and militia; he also brought a regiment of friendly Creeks from Alabama who had been involved in the Second Creek War.[53] The force also included a brigade of Marines, and Navy and United States Revenue Cutter Service (AKA: Revenue Marine) personnel patrolling the coast and inland rivers and streams. In all the Revenue Marine committed 8 Cutters to operations in Florida during the war.[54]

The U.S. Navy and the Revenue Marine both worked with the Army from the beginning of the war. Navy ships and revenue cutters ferried men and supplies to Army posts. They patrolled the Florida coast to gather information on and intercept Seminoles, and to block smuggling of arms and supplies to the Seminoles. Sailors and Marines helped man Army forts that were short of manpower. Sailors, Marines, and the Cuttermen of the Revenue Marine participated in expeditions into the interior of Florida, both by boat and on land. Against those numbers the Seminoles had started the war with between 900 and 1,400 warriors, and with no means of replacing their losses.[55] The total population of the Seminoles in 1836 was estimated at 6,000 up to 10,000 people.[56]

Truce and reversal

January 1837 saw a change in the war. In various actions a number of Seminoles and Black Seminoles were killed or captured. At the Battle of Hatchee-Lustee, the Marine brigade, "succeeded in capturing the horses and baggage of the enemy, with twenty-five Indians and negroes, principally women and children."[57] At the end of January some Seminole chiefs sent messengers to Jesup, and a truce was arranged. Fighting did not stop right away, and a meeting between Jesup and the chiefs did not occur until near the end of February. In March a 'Capitulation' was signed by a number of chiefs, including Micanopy, stipulating that the Seminoles could be accompanied by their allies and "their negroes, their 'bona fide' property" in their relocation to the West.[58]

Even as Seminoles began to come into the Army camps to await transportation west, slave catchers were claiming blacks living with the Seminoles. As the Seminoles had no written records of ownership, they generally lost in disputes over ownership. Other whites were trying to have Seminoles arrested for alleged crimes or debts. All of this made the Seminoles suspicious of promises made by Jesup. On the other hand, it was noted that many of the warriors coming into the transportation camps had not brought their families, and seemed mainly to be interested in collecting supplies. By the end of May, many chiefs, including Micanopy, had surrendered. Two important leaders, Osceola and Ar-pi-uck-i (Sam Jones), had not surrendered, however, and were known to be vehemently opposed to relocation. On June 2 these two leaders with about 200 followers entered the poorly guarded holding camp at Fort Brooke and led away the 700 Seminoles there who had surrendered.[59]

The war did not immediately resume on a large scale. General Jesup had thought that the surrender of so many Seminoles meant the war was ending, and had not planned a long campaign. Many of the soldiers had been assigned elsewhere, or, in the case of militias and volunteers, released from duty. It was also getting into summer, the 'sickly season', and the Army did not fight aggressively in Florida during the summer. The Panic of 1837 was reducing government revenues, but Congress appropriated another US$1.6 million for the war. In August the Army stopped supplying rations to civilians who had taken refuge at its forts.[60]

Captures and false flags

Jesup kept pressure on the Seminoles by sending small units into the field. Many of the blacks with the Seminoles began turning themselves in. After a couple of swings in policy on dealing with fugitive slaves, Jesup ended up sending most of them west to join the Seminoles that were already in Indian territory. On September 10, 1837, the Army and militias captured a band of Mikasukis including King Phillip, one of the most important chiefs in Florida. The next night the same command captured a band of Yuchis, including their leader, Uchee Billy.[61]

General Jesup had King Phillip send a message to his son Coacoochee (Wild Cat) to arrange a meeting with Jesup. When Coacoochee arrived under a flag of truce, Jesup arrested him. In October Osceola and Coa Hadjo, another chief, requested a parley with Jesup. A meeting was arranged south of St. Augustine. When Osceola and Coa Hadjo arrived for the meeting, also under a white flag, they were arrested. Osceola was dead within three months of his capture, in prison at Fort Moultrie in Charleston, South Carolina. Not all of the Seminoles captured by the Army stayed captured. While Osceola was still held at Fort Marion (Castillo de San Marcos) in St. Augustine, twenty Seminoles held in the same cell with him and King Phillip escaped through a narrow window. The escapees included Coacoochee and John Horse, a Black Seminole leader.[62] "Undoubtedly the general violated the rules of civilized warfare...[and] he was still writing justifications of it twenty-one years later" for an act that "hardly seems worthwhile to try to grace the capture with any other label than treachery."[63]

A delegation of Cherokee was sent to Florida to try to talk the Seminoles into moving west. When Micanopy and others came in to meet the Cherokees, General Jesup had the Seminoles held. John Ross, the head of the Cherokee delegation, protested, but to no avail. Jesup replied that he had told the Cherokees that no Seminole who came in would be allowed to return home.[64]

Zachary Taylor and the Battle of Lake Okeechobee

Jesup now had a large army assembled, including volunteers from as far away as Missouri and Pennsylvania—so many men, in fact, that he had trouble feeding all of them. Jesup's plan was to sweep down the peninsula with multiple columns, pushing the Seminoles further south. General Joseph Marion Hernández led a column down the east coast. General Eustis took his column up the St. Johns River (southward). Colonel Zachary Taylor led a column from Fort Brooke into the middle of the state, and then southward between the Kissimmee River and the Peace River. Other commands cleared out the areas between the St. Johns and the Oklawaha River, between the Oklawaha and the Withlacoochee River, and along the Caloosahatchee River. A joint Army-Navy unit patrolled the lower east coast of Florida. Other troops patrolled the northern part of the territory to protect against Seminole raids.[65]

Colonel Taylor saw the first major action of the campaign. Leaving Fort Gardiner on the upper Kissimmee with 1,000 men on December 19, Taylor headed towards Lake Okeechobee. In the first two days out ninety Seminoles surrendered. On the third day Taylor stopped to build Fort Basinger, where he left his sick and enough men to guard the Seminoles that had surrendered. Three days later, on Christmas Day, 1837, Taylor's column caught up with the main body of the Seminoles on the north shore of Lake Okeechobee.[66]

The Seminoles led by Halpatter Tustenuggee (Alligator]), Ar-pi-uck-i (Sam Jones), and the recently escaped Coacoochee, were well positioned in a hammock surrounded by sawgrass. The ground was thick mud, and sawgrass easily cuts and burns the skin. Taylor had about 800 men, while the Seminoles numbered less than 400. Taylor sent the Missouri volunteers in first. Colonel Richard Gentry, three other officers and more than twenty enlisted men were killed before the volunteers retreated. Next in were 200 soldiers of the 6th Infantry, who lost four officers and suffered nearly 40% casualties before they withdrew. Then it was the turn of the 4th Infantry, 160 men augmented by remnants of the 6th Infantry and the Missouri volunteers. This time the troops were able to drive the Seminoles from the hammock and towards the lake. Taylor then attacked their flank with his reserves, but the Seminoles were able to escape across the lake. Only about a dozen Seminoles had been killed in the battle. Nevertheless, the Battle of Lake Okeechobee was hailed as a great victory for Taylor and the Army.[67]

The Battle of Loxahatchee

Taylor now joined the other columns sweeping down the peninsula to pass on the east side of Lake Okeechobee, under the overall command of General Jesup. The troops along the Caloosahatchee River blocked any passage north on the west side of the lake. Still patrolling the east coast of Florida was the combined Army-Navy force under Navy Lt. Levin Powell. On January 15, Powell, in the Battle of Jupiter Inlet, led eighty men towards a Seminole camp only to find themselves outnumbered by the Seminoles. A charge against the Seminoles was unsuccessful, but the troops made it back to their boats after losing four dead and twenty-two wounded. The party's retreat was covered by Army Lt. Joseph E. Johnston. At the end of January, Jesup's troops caught up with a large body of Seminoles to the east of Lake Okeechobee. The Seminoles were originally positioned in a hammock, but cannon and rocket fire drove them back across a wide stream (the Loxahatchee River), where they made another stand. The Seminoles eventually just faded away, having caused more casualties than they received, and the Battle of Loxahatchee was over.[68]

The fighting now died down. In February 1838, Seminole chiefs Tuskegee and Halleck Hadjo approached Jesup with the proposition that they would stop fighting if they were allowed to stay south of Lake Okeechobee. Jesup favored the idea, foreseeing a long struggle to capture the remaining Seminoles in the Everglades, and calculating that the Seminoles would be easier to round up later when the land was actually needed by white settlers. However, Jesup had to write to Washington for approval. The chiefs and their followers camped near the Army while awaiting the reply, and there was considerable fraternizing between the two camps. Secretary of War Joel Roberts Poinsett rejected the arrangement, however, and instructed Jesup to continue his campaign. Upon receiving Poinsett's response, Jesup summoned the chiefs to his camp, but they refused his invitation. Unwilling to let 500 Seminoles return to the swamps, Jesup sent a force to detain them. The Seminoles offered very little resistance, perhaps seeing little reason to continue fighting.[69]

Loxahatchee River Battlefield Park preserves an area of the fighting. Memorials are also located in Jonathan Dickinson State Park.

Jesup steps down; Zachary Taylor takes command

Jesup asked to be relieved of his command. As summer approached in 1838 the number of troops in Florida dwindled to about 2,300. In April, Jesup was informed that he should return to his position as Quartermaster General of the Army. In May, Zachary Taylor, now a General, assumed command of the Army forces in Florida. With reduced forces in Florida, Taylor concentrated on keeping the Seminole out of northern Florida, so that settlers could return to their homes. The Seminoles were still capable of reaching far north. In July they were thought responsible for the deaths of a family on the Santa Fe River, another near Tallahassee, as well as two families in Georgia. The fighting died down during the summer, as the soldiers were pulled back to the coasts. The Seminoles concentrated on growing their crops and gathering supplies for fall and winter.[70]

Taylor's plan was to build small posts at frequent intervals across northern Florida, connected by wagon roads, and to use larger units to search designated areas. This was expensive, but Congress continued to appropriate the necessary funds. In October 1838, Taylor relocated the last of the Seminole living along the Apalachicola River to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Killings in the Tallahassee area caused Taylor to pull troops out of southern Florida to provide more protection in the north. The winter season was fairly quiet. The Army killed only a few Seminole and transported fewer than 200 to the West. Nine U.S. troops were killed by the Seminoles. Taylor reported in the Spring of 1839 that his men had constructed 53 new posts and cut 848 miles (1,365 km) of wagon roads.[71]

Macomb's peace and the Battle of Caloosahatchee

In Washington and around the country in 1839, support for the war was eroding. The size of the Army had been increased because of the demands for manpower in the Florida war. Many people were beginning to think that the Seminole had earned a right to stay in Florida. The cost and time required to get all the Seminole out of Florida were looming larger. Congress appropriated US$5,000 to negotiate a settlement with the Seminole people in order to end the outlay of resources. President Martin Van Buren sent the Commanding General of the Army, Alexander Macomb, to negotiate a new treaty with the Seminole. Remembering the broken treaties and promises of the past, they were slow to respond to the new overtures. Finally, Abiaka (Sam Jones) sent his chosen successor, Chitto Tustenuggee, to meet with Macomb. On May 19, 1839, Macomb announced reaching agreement with the Seminole. They would stop fighting in exchange for a reservation in southern Florida.[72]

As the summer passed, the agreement seemed to be holding. There were few killings. A trading post was established on the north shore of the Caloosahatchee River, near present-day Cape Coral, and the Seminoles who came to the trading post seemed to be friendly. A detachment of 23 soldiers was stationed at the Caloosahatchee trading post under the command of Colonel William S. Harney. On July 23, 1839, some 150 Indians, including Holato Micco (Billy Bolek or Bowlegs) and two other leaders named Chakaika and Hospertarke, attacked the trading post and guard.[73][74] Some of the soldiers, including Colonel Harney, were able to reach the river and find boats to escape in, but most of the soldiers, as well as a number of civilians in the trading post, were killed. The war was on again.[75]

The Americans did not know which band of Indians had attacked the trading post. Many blamed the 'Spanish' Indians, led by Chakaika. Some suspected Abiaka (Sam Jones), whose band of Mikasuki had come to agreement with Macomb. Jones promised to turn the men responsible for the attack over to Harney in 33 days. In the meantime, the Mikasuki in Sam Jones' camp near Fort Lauderdale remained on friendly terms with the local soldiers. On July 27 they invited the officers at the fort to a dance at the Mikasuki camp. The officers declined but sent two soldiers and a Black Seminole interpreter with a keg of whiskey. The Mikasuki killed the soldiers, but the Black Seminole escaped. He reported at the fort that Abiaka and Chitto Tustenuggee were involved in the attack. In August 1839, Seminole raiding parties operated as far north as Fort White.[76]

New tactics

The Army decided to use bloodhounds to track the Seminoles. (General Taylor had requested and received permission to buy bloodhounds in 1838) "Taylor accepted two of them for trial...the hounds failed their tests. They were trained to track Negros...and could not be induced to nose out Indians."[77][78] In early 1840, the Florida territorial government purchased bloodhounds from Cuba and hired Cuban handlers. Initial trials of the hounds had mixed results, and a public outcry arose against the use of the dogs, based on fears that they would be set on the Seminoles in physical attacks, including against women and children. The Secretary of War ordered the dogs to be muzzled and kept on leashes while tracking. Bloodhounds could not track through water, however "tracks of Indians were found, but the dogs finding the scent far different from that of a negro, refused to follow [them]."[79][80][81]

In the north of Florida, Taylor's blockhouse and patrol system kept the Seminole on the move, but the Army could not clear them from the area. Ambushes of travelers were common. On February 13, 1840, the mail stage between St. Augustine and Jacksonville was ambushed. In May Seminole attacked a theatrical troupe near St. Augustine, killing a total of six people. In the same month, a group of four soldiers traveling between forts in Alachua County was attacked, with one killed and two others never seen again. A party of eighteen men pursued the Indians, but six were killed.[82]

In May 1840, Zachary Taylor, having served longer than any preceding commander in the Florida war, was granted his request for a transfer. He was replaced by Brig. Gen. Walker Keith Armistead, who had earlier served in Florida as second in command to General Jesup. Armistead began an offensive, sending out 100 soldiers at a time to search for the Seminole and their camps. For the first time, the Army campaigned in Florida during the summer, taking captives and destroying crops and buildings. The Seminole also were active in warfare, killing fourteen soldiers during July.[83] The Army worked to find the Seminole camps, burn their fields and stores of food, and drive off their livestock, including their horses.[84]

Armistead planned to turn over the defense of Florida north of Fort King to the militia and volunteers. He wanted to use Army regulars to confine the Seminole to south of Fort King, and pursue them within that territory. The Army destroyed camps and fields across central Florida, a total of 500 acres (2.0 km2) of Seminole crops by the middle of the summer. General Armistead became estranged from the territorial government, although he needed 1,500 militiamen from the Territory to defend the area north of Fort King. To bolster the effort south of Fort King, the Army sent the Eighth Infantry Regiment to Florida. The Army in Florida now included ten companies of the Second Dragoon, nine companies of the Third Artillery, and the First, Second, Third, Sixth, Seventh and Eighth Infantry Regiments.[85]

Changes were also being made in southern Florida. At Fort Bankhead on Key Biscayne, Col. Harney instituted an intensive training program in swamp and jungle warfare for his men.[86] The Navy took a larger role in the war, sending manned boats with sailors and marines up rivers and streams, and into the Everglades.[87]

The "Mosquito Fleet"

In the early years of the war, Navy Lt. Levin Powell had commanded a joint Army-Navy force along with 8 Revenue Cutters of some 200 plus men that operated along the coast. In late 1839, Navy Lt. John T. McLaughlin was given command of a joint Army-Navy force supported by the Revenue Marine. This included schooners and cutters off the shores, barges close to the mainland to intercept Cuban and Bahamian traders bringing arms and other supplies to the Seminoles, and smaller boats, down to canoes, for patrolling up rivers and into the Everglades. McLaughlin established his base at Tea Table Key in the upper Florida Keys.[88]

An attempt to cross the Everglades from west to east was launched in April 1840, but the sailors and marines were engaged by Seminoles at the rendezvous point on Cape Sable. Although there were no known fatalities (the Seminoles carried off their dead and wounded), many of the naval personnel became ill, and the expedition was called off and the sick were taken to Pensacola. For the next few months the men of Lt. McLaughlin's force explored the inlets and rivers of southern Florida.[89] McLaughlin did lead a force across the Everglades later. Traveling from December 1840 to the middle of January 1841, McLaughlin's force crossed the Everglades from east to west in dugout canoes, the first groups of whites to complete a crossing.[90]

Indian Key

Indian Key is a small island in the upper Florida Keys which had developed into a base for wreckers. In 1836 it became the county seat of the newly created Dade County and a port of entry. Despite fears of attack and sightings of Indians in the area, the inhabitants of Indian Key stayed to protect their property, and to be close to any wrecks in the upper Keys. The islanders had six cannons and their own small militia company for their defense, and the Navy had established a base on nearby Tea Table Key.[91]

Early in the morning of August 7, 1840, a large party of Spanish Indians snuck onto Indian Key. By chance, one man was up and raised the alarm after spotting the Indians. Of about fifty people living on the island, forty were able to escape. The dead included Dr. Henry Perrine, former United States Consul in Campeche, Mexico, who was waiting at Indian Key until it was safe to take up a 36 sq mi (93 km2) grant on the mainland that Congress had awarded to him.[92]

The naval base on Tea Table Key had been stripped of personnel for an operation on the southwest coast of the mainland, leaving only a physician, his patients, and five sailors under a midshipman to look after them. This small contingent mounted a couple of cannons on barges and tried to attack the Indians on Indian Key. The Indians fired back at the sailors with musket balls loaded in one of the cannons on shore. The recoil of the cannons on the barges broke them loose, sending them into the water, and the sailors had to retreat. The Indians burned the buildings on Indian Key after thoroughly looting it.[93]

Revenge and negotiations

In December 1840, Colonel William S. Harney led ninety men into the Everglades from Fort Dallas on the Miami River, traveling in canoes borrowed from the Marines. They were guided by a black man named John who had been in Seminole captivity for some time. The column encountered some Indians in canoes and gave chase, catching some of them and promptly hanging the men. When John was having trouble finding the way, Harney tried to force the captured Seminole women to lead the way to the camp, reportedly by threatening to hang their children. However, John got his bearings again and the Harney party found the camp of Chakaika and the 'Spanish Indians'. Dressed as Indians, the soldiers approached the camp early in the morning, achieving surprise. Chakaika was outside the camp when the attack started. He started to run and then stopped and turned to face the soldiers, offering his hand, but one of the soldiers shot and killed him. There was a brief fight during which some of the Indians escaped. Harney had two of the captured warriors hanged, and had Chakaika's body hung beside them. Harney and his men returned to Fort Dallas after twelve days in the Everglades. Harney had lost one soldier killed. His command had killed four Indians in action and hanged five more. The Legislative Council of Florida presented Harney with a commendation and a sword, and Harney was soon given command of the Second Dragoons.[94]

Armistead had US$55,000 ($1.8 million in 2025 dollars) to use for bribing chiefs to surrender. In November 1840, General Armistead met at Fort King with Thlocklo Tustenuggee, a Muscogee speaker known as "Tiger Tail", and Halleck Tustenuggee, a Mikasuki speaker. Armistead was authorized by Washington to offer each leader $5,000 ($115,023) to bring their followers in for transportation west, and to concede land in the south of Florida to those remaining. However, Colonel Ethan A. Hitchcock recorded in his diary, with considerable frustration, that the General instead pocketed these proposals and insisted the chiefs agree to the terms of the Payne's Landing treaty. Moreover, while talking peace, he secretly sent a force threatening Halleck's people at his home. After several days as guests of the Army both chiefs fled in the middle of the night on November 14, 1840.[95] Echo Emathla, a Tallahassee chief, surrendered, but most of the Tallahassee, under Thlocklo Tustenuggee, did not. The Mikasukis, led by Coosa Tustenuggee and Halleck Tustenuggee, continued to operate in the northern part of the Florida peninsula. Coosa Tustenuggee finally accepted $5,000 for bringing in his sixty people. Lesser chiefs received $200 ($4,601), and every warrior $30 ($690) and a rifle. Coacoochee took advantage of Armistead's willingness to negotiate. In March 1841, he agreed to bring in his followers in two or three months. During that time, he appeared at several forts, presenting the pass given to him by Armistead, and demanding food and liquor. On one visit to Fort Pierce, Coacoochee demanded a horse to ride to Fort Brooke. The fort commander gave him one, along with five and one-half gallons of whiskey.[96]

By the spring of 1841, Armistead had sent 450 Seminoles west. Another 236 were at Fort Brooke awaiting transportation. Armistead estimated that 120 warriors had been shipped west during his tenure, and that there were no more than 300 warriors left in Florida. In May 1841, Halleck Tustenuggee sent word that he would be bringing his band in to surrender.[97]

Colonel Worth takes charge

In May 1841, Armistead was replaced by Col. William Jenkins Worth as commander of Army forces in Florida. Due to the unpopularity of the war in the nation and in Congress, Worth had to cut back. The war was costing US$93,300 per month in addition to the pay of the regular soldiers. John T. Sprague, Worth's aide, believed that some civilians were trying to deliberately prolong the war in order to stay on the government payroll. Nearly 1,000 civilian employees of the Army were released, and smaller commands were consolidated. Worth then ordered his men out on what would now be called 'search and destroy' missions during the summer. These efforts effectively drove the Seminoles out of their old stronghold in the Cove of the Withlacoochee. Much of the rest of northern Florida was also cleared by these methods.[98]

On May 1, 1841, Lieutenant William Tecumseh Sherman was assigned to escort Coacoochee to a meeting at Fort Pierce. (The fort was named for Colonel Benjamin Kendrick Pierce, who oversaw its construction.) After washing and dressing in his best (which included a vest with a bullet hole and blood on it), Coacoochee asked Sherman to give him silver in exchange for a one-dollar bill from the Bank of Tallahassee. At the meeting Major Thomas Childs agreed to give Coacoochee thirty days to bring in his people for transportation west. Coacoochee's people came and went freely at the fort for the rest of the month, while Childs became convinced that Coachoochee would renege on his agreement. Childs asked for and received permission to seize Coacoochee. On June 4 he arrested Coachoochee and fifteen of his followers. Lieutenant Colonel William Gates ordered that Coacoochee and his men be shipped immediately to New Orleans. When Colonel Worth learned of this, he ordered the ship to return to Tampa Bay, as he intended to use Coacoochee to persuade the rest of the Seminoles to surrender.[99]

Colonel Worth offered bribes worth about US$8,000 to Coacoochee. As Coacoochee had no real hope of escaping, he agreed to send out messengers urging the Seminoles to move west. The chiefs still active in the northern part of the Florida peninsula, Halleck Tustenuggee, Tiger Tail, Nethlockemathla, and Octiarche, met in council and agreed to kill any messengers from the whites. The southern chiefs seemed to have learned of this decision, and supported it. However, when one messenger appeared at a council of Holata Mico, Sam Jones, Otulkethlocko, Hospetarke, Fuse Hadjo and Passacka, he was made prisoner, but not killed.[100]

A total of 211 Seminoles surrendered as a result of Coacoochee's messages, including most of his own band. Hospetarke was drawn into a meeting at Camp Ogden (near the mouth of the Peace River) in August and he and 127 of his band were captured. As the number of Seminoles in Florida decreased, it became easier for those left to stay hidden. In November the Third Artillery moved into the Big Cypress Swamp and burned a few villages. Some of the Seminoles in southern Florida gave up after that, and turned themselves in for transportation west.[101]

Seminoles were still scattered throughout most of Florida. One band that had been reduced to starvation surrendered in northern Florida near the Apalachicola River in 1842. Further east, however, bands led by Halpatter Tustenuggee, Halleck Tustenuggee and Chitto Hadjo raided Mandarin and other settlements along the lower (i.e., northern) St. Johns River. On April 19, 1842, a column of 200 soldiers led by First Lieutenant George A. McCall found a group of Seminole warriors in the Pelchikaha Swamp, about thirty miles south of Fort King. There was a brief fire-fight and then the Seminoles disappeared into a hammock. Halleck Tustenuggee was held prisoner when he showed up at Fort King for a talk. Part of his band was caught when they visited the fort, and Lieutenant McCall captured the rest of Halleck's band in their camp.[102]

The war winds down

Colonel Worth recommended early in 1842 that the remaining Seminoles be left in peace if they would stay in southern Florida. Worth eventually received authorization to leave the remaining Seminoles on an informal reservation in southwestern Florida, and to declare an end to the war on a date of his choosing. At this time there were still several diverse bands of Indians in Florida. Billy Bowlegs was the head of a large band of Seminoles living near Charlotte Harbor. Sam Jones led a band of Mikasukis that lived in the Everglades near Fort Lauderdale. North of Lake Okeechobee was a band of Muskogees led by Chipco. Another Muskogee band, led by Tiger Tail, lived near Tallahassee. Finally, in northern Florida there was a band of Creeks led by Octiarche which had fled from Georgia in 1836.[103]

In August 1842, Congress passed the Armed Occupation Act, which provided free land to settlers who improved the land and were prepared to defend themselves from Indians. In many ways this act prefigured the Homestead Act of 1862. Heads of households could claim 160 acres (0.6 km2) of land south of a line running across the northern part of the peninsula. They had to 'prove' their claim by living on the land for five years and clearing 5 acres (20,000 m2). However, they could not claim land within two miles (3.2 km) of a military post. A total of 1,317 grants totaling 210,720 acres (853 km2) were registered in 1842 and 1843.[104]

In the last action of the war, General William Bailey and prominent planter Jack Bellamy led a posse of 52 men on a three-day pursuit of a small band of Tiger Tail's braves who had been attacking pioneers, surprising their swampy encampment and killing all 24. William Wesley Hankins, at sixteen the youngest of the posse, accounted for the last of the kills and was acknowledged as having fired the last shot of the Second Seminole War.[105]

Also in August 1842, Worth met with the chiefs still in Florida. Each warrior was offered a rifle, money and one year's worth of rations if they moved west. Some accepted the offer, but most hoped to eventually move to the reservation in southwest Florida. Believing that the remaining Indians in Florida would either go west or move to the reservation, Worth declared the war to be at an end on August 14, 1842. Worth then went on ninety-days leave, leaving command to Colonel Josiah Vose. The Army in Florida consisted at this point of parts of three regiments, totaling 1,890 men. Attacks on white settlers continued even as far north as the area around Tallahassee. Otiarche and Tiger Tail had not indicated what they would do. Complaints from Florida caused the War Department to order Vose to take action against the bands still off the reservation, but Vose argued that breaking the pledges made to the Indians would have bad results, and the War Department accepted his arguments. In early October a major hurricane struck Cedar Key, where the Army headquarters had been located, and the Indians would no longer visit it.[106]

Worth returned to Florida at the beginning of November 1842. He soon decided that Tiger Tail and Otiarche had taken too long to make up their minds on what to do, and ordered that they be brought in. Tiger Tail was so ill that he had to be carried on a litter, and he died in New Orleans waiting for transportation to the Indian territory. The other Indians in northern Florida were also captured and sent west. By April 1843, only one regiment, the Eighth Infantry, was still in Florida. In November 1843 Worth reported that the only Indians left in Florida were 42 Seminole warriors, 33 Mikasukis, 10 Creeks and 10 Tallahassees, with women and children bringing the total to about 300. Worth also stated that these Indians were all living on the reservation and were no longer a threat to the white population of Florida.[107]

Costs

Mahon cites estimates of US$30,000,000 to $40,000,000 as the cost of the Second Seminole War, but knew of no analysis of the actual cost. Congress appropriated funds for the 'suppression of Indian hostilities', but the costs of the Creek War of 1836 are included in that. An inquiry in extravagance in naval operations found that the Navy had spent about US$511,000 on the war. The investigation did find questionable expenditures. Among other things, while the Army had bought dugout canoes for $10 to $15 apiece, the Navy spent an average of $226 per canoe. The number of Army, Navy and Marine regulars who served in Florida is given as 10,169. About 30,000 militiamen and volunteers also served in the war.[6]

By the spring 1841, the paymaster general issued a report that found the U.S. government had issued $2,500,000 in payroll to regular army soldiers and an additional $3,500,000 in payroll to citizen soldiers.[108]

Sources agree that the U.S. Army officially recorded 1,466 deaths in the Second Seminole War, mostly from disease. The number killed in action is less clear. Mahon reports 328 regular Army killed in action, while Missall reports that Seminoles killed 269 officers and men. Almost half of those deaths occurred in the Dade Massacre, Battle of Lake Okeechobee and Harney Massacre. Similarly, Mahon reports 69 deaths for the Navy while Missall reports 41 for the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps, but adds others may have died after being sent out of Florida as incurable. Mahon and the Florida Board of State Institutions agree that 55 volunteer officers and men were killed by the Seminoles, while Missall says the number is unknown. There is no figure for how many militiamen and volunteers died of disease or accident, however.[109]

The number of white civilians, Seminoles and Black Seminoles killed is uncertain. A northern newspaper carried a report that more than 80 civilians were killed by Indians in Florida in 1839. Nobody was keeping a cumulative account of the number of Indians and Black Seminoles killed, or the number who died of starvation or other privations caused by the war. The people shipped west did not fare well, either. By the end of 1843, 3,824 Indians (including 800 Black Seminoles) had been shipped from Florida to what became the Indian Territory. They were initially settled on the Creek Reservation, which created tensions. The next year, the Florida people numbered 3,136. As of 1962, their numbers had dropped to 2,343 Seminoles in the Indian Territory and perhaps some 1,500 in Florida.[109]

Aftermath

Peace had come to Florida for a while. The Natives were mostly staying on the reservation, but there were minor clashes. The Florida authorities continued to press for removal of all Natives from Florida. The Natives tried to limit their contacts with the American settlers as much as possible.

As time went on there were more serious incidents. The government resolved once more to remove all Indians from Florida, and applied increasing pressure on the Seminoles until they struck back, starting the Third Seminole War of 1855–1858.[110]

See also

- Black Seminoles

- History of Florida

- Indian Campaign Medal

- Population transfer

- Seminole (tribe)

- Distant Drums

Notes

- ^ In the 17th century the Spanish in Florida used cimaron to refer to christianized natives who had left their mission villages to live "wild" in the woods.[15]

- ^ Ransom Clark was permanently crippled for life, and could not physically work for a living; he supported himself, his wife and daughter from a monthly $8.00 U.S. Gov't Army disability check, and conducting lectures, along with his "short" book. Clark mentioned when promoting his book, that he intended on writing a fuller account of his life and the war; succumbing to his shoulder wound, which became infected, he died too young to write his book. Author Frank Laumer, a native of Florida, who studied the Seminole War, and Ransom Clark in particular for over 40 years, finally got Ransom Clark's book written and published in 2008; 168 years later.[citation needed]

References

- ^ Rhodes, Rick (2003). Cruising Guide to Florida's Big Bend: Apalachicola, Chattahoochee, Flint, and Suwanee Rivers. Gretna, Louisiana: Pelican Publishing Company. pp. 20–21. ISBN 978-1-58980-072-4.

- ^ Schultz, Jack Maurice (1999). The Seminole Baptist Churches of Oklahoma: Maintaining a Traditional Community. Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8061-3117-7.

- ^ Swanton, John Reed (1922). Early History of the Creek Indians and Their Neighbors, Issue 73. Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office. p. 443.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer C. (2011). Encyclopedia of North American Indian Wars, 1607–1890. Vol. 1. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 719. ISBN 978-1-85109-697-8.

- ^ Missall 122–25

- ^ a b Mahon 323, 325

- ^ Ellisor 339

- ^ Buker 11

It is not clear whether this number includes Black Seminoles who often fought alongside the Seminoles. - ^ Mahon 318

- ^ Mahon 321, 325.

Missall 177, 204–205.

Florida Board of State Institutions. 9. - ^ Foner, Eric (2006). Give me liberty. Norton.

- ^ Mahon 321

- ^ Lancaster 18.

- ^ Bauer, P. (2021, December 21). "Second Seminole War". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ^ Hann, John H. (1992). "Heathen Acuera, Murder, and a Potano Cimarrona: The St. Johns River and the Alachua Prairie in the 1670s". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 70 (4): 451–474. ISSN 0015-4113. JSTOR 30148124.

- ^ Missall 4–7, 128

Knetsch 13

Buker 9–10

Sturtevant 39–41 - ^ Buker 1997, p. 11.

- ^ Missall 55, 39–40

- ^ Missall 55, 63–64

- ^ Cubberly, Fred (January 1927). "Fort King". The Florida Historical Society Quarterly. 5 (3): 139–152. JSTOR 30150749. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Missall 75–76

- ^ a b Mahon p. 251

- ^ a b Mahon p. 20

- ^ Missall 78–80

- ^ a b Missall 83–85

- ^ Meltzer 76

- ^ Missall 86–90

- ^ Missall 90–91

- ^ Missall 91–92

- ^ Missall 93–94

- ^ Laumer p. 270 (2008)

- ^ a b Laumer p. 266 (2008)

- ^ Missall 97

Knetsch 71–72

Mahon 106

Thrapp "Clark(e), Ransom" 280 - ^ Hitchcock 120–131

- ^ Missall 97–100

- ^ Vone Research.

- ^ Missall 100

- ^ Buker, p 1

- ^ Knetsch. P. 71.

- ^ Missall 100–105

- ^ Brown, M.L. (1982). "Notes on U.S. Arsenals, Depots, and Martial Firearms of the Second Seminole War". Florida Historical Quarterly. 61 (4): 445. Retrieved February 16, 2024.

- ^ Missall 105–107

- ^ Mahon 147–150

Missall 107–109 - ^ Missall 111–112

- ^ Cox, Dale (2016). Fort Scott, Fort Hughes & Camp Recovery. Three 19th century military sites in Southwest Georgia. Old Kitchen Books. ISBN 9780692704011.

- ^ Missall 112–114

- ^ Mahon 158–160, 173–174, 176

- ^ Mahon 173–176

- ^ Missall 114–118

- ^ Missall 117–119

- ^ Hauptman, Laurence M.; Dixon, Heriberto (September 2008). "Cadet David Moniac: A Creek Indian's Schooling at West Point, 1817-1822". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 152 (3): 322–342. JSTOR 40541590. PMID 19831231. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Missall 120–121

- ^ Ellisor, John T. (2010). The Second Creek War. University of Nebraska Press. p. 328.

- ^ Missall 122–125

- ^ Buker 11, 16–31

- ^ Index to the miscellaneous documents of the House of Representatives for the first session of the forty-ninth Congress, 1885-86. In twenty-six volumes. Washington: Government Printing Office. 1886. p. 896.

- ^ Spraque p. 170

- ^ Missall 126–128

- ^ Missall 128–129

- ^ Missall 131–132

- ^ Missall 132–134

- ^ Missall 134, 140–141

- ^ Mahon p. 217

- ^ Missall 141

- ^ Missall 138–139

- ^ Missall 142

- ^ Missall 142–143

- ^ Missall 144–145

Chapman, Kathleen. (2009) "Artifacts found, collected from forgotten Loxahatchee battle from 1838". Palm Beach Post. at [1] Archived June 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine - ^ Missall 146–147, 151

- ^ Missall 152, 157–158

- ^ Missall 152, 159–160

- ^ Missall 152, 162–164

- ^ Patsis, Matt. "The Battle of Caloosahatchee" (PDF). Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Adams, George R. (April 1970). "The Caloosahatchee Massacre: Its Significance in the Second Seminole War". The Florida Historical Quarterly. 48 (4): 376. Retrieved April 26, 2023.

- ^ Missall 165–166

- ^ Missall 167–168

- ^ Mahon p. 266

- ^ Sprague "The Florida War" p. 239, 240

- ^ Sprague p. 240

- ^ Missall 169–173

- ^ Parry, Tyler D.; Yingling, Charlton W. (February 1, 2020). "Slave Hounds and Abolition in the Americas". Past & Present (246): 69–108. doi:10.1093/pastj/gtz020. ISSN 0031-2746.

- ^ Missall 176–178, 182–4

- ^ Missall 178, 182–4

- ^ Covington 98–99

- ^ Mahon 276–81

- ^ Blank 1996, pp. 44–49.

- ^ Missall 176–178

- ^ Buker 99–101

- ^ Buker. pp. 103–104.

- ^ Mahon 289

- ^ Viele 1996, pp. 33–35.

- ^ Viele 1996, p. 35.

- ^ Buker 106–107

- ^ Mahon 283–4

- ^ Fifty Years in Camp and Field: Diary of Major-General Ethan Allen Hitchcock, U.S.A., pp. 122–123.

- ^ Mahon 282, 285–7

- ^ Mahon 287

- ^ Knetsch 128–131

Mahon 298 - ^ Mahon 298–9

- ^ Mahon 299–300

- ^ Covington 103–4

- ^ Covington 105–6

- ^ Covington 107

- ^ Mahon 313–4

- ^ D. B. McKay's "Pioneer Florida", "Buckshot from 26 Shotguns Swept Band of Ferocious, Marauding Seminoles Off Face of The Earth", The Tampa Tribune, June 27, 1954, p. 16-C

- ^ Mahon 316–7

- ^ Mahon 317–8

- ^ Matthews 110

- ^ a b Mahon 321, 325

Missall 177, 204–205

Florida Board of State Institutions 9 - ^ Covington 110–27

Sources

- Blank, Joan (1996). Key Biscayne : a history of Miami's tropical island and the Cape Florida lighthouse (1st ed.). Sarasota, Fla.: Pineapple Press. ISBN 1561640964.

- Buker, George E. (1975) Swamp Sailors: Riverine Warfare in the Everglades 1835–1842. Gainesville, Florida:The University Presses of Florida.

- Buker, George E. (1997). Swamp Sailors in the Second Seminole War. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 9780813015149.

- Covington, James W. (1993). The Seminoles of Florida. Gainesville, Fla.: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1196-5.

- Florida Board of State Institutions. (1903) Soldiers of Florida in the Seminole Indian, Civil and Spanish–American Wars. at Internet Archive – Ebooks and Texts Archive – URL retrieved November 22, 2010.

- Hitchcock, Ethan Allen. (1930) Edited by Grant Foreman. A Traveler in Indian Territory: The Journal of Ethan Allen Hitchcock, Late Major-General in the United States Army. Cedar Rapids, Iowa: Torch.

- Knetsch, Joe. (2003) Florida's Seminole Wars: 1817–1858. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-7385-2424-7.

- Lancaster, Jane F. (1994) Removal Aftershock: The Seminoles' Struggles to Survive in the West, 1836–1866. Knoxville, Tennessee: The University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-845-2

- Laumer, Frank. (2008). Nobody's Hero. A novel[a] The story of Pvt. Ransom Clark, survivor of Dade's Battle, 1835. Pineapple Press, Inc. Sarasota, Florida.

- Mahon, John K. (1967) History of the Second Seminole War 1835–1842. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press.

- Matthews, Janet Snyder (1983). Edge of Darkness: A Settlement History of Manatee River and Sarasota Bay. Tulsa, OK: Caprine Press. ISBN 0914381008.

- Meltzer, Milton (2004). Hunted Like a Wolf : the Story of the Seminole War. Sarasota, Fla.: Pineapple Press. ISBN 1-56164-305-X.

- Milanich, Jerald T. (1995). Florida Indians and the invasion from Europe. Gainesville, Fla.: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1360-7.

- Missall, John; Missall, Mary Lou (2004). The Seminole wars : America's longest Indian conflict. Gainesville, Fla.: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2715-2.

- Office of the Chief of Military History, United States Army. (2001) Chapter 7: The Thirty Years' Peace Archived January 15, 2016, at the Wayback Machine. American Military History Archived December 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. P. 153. Retrieved October 22, 2006.

- Officers of 1–5 FA. (1999) 1st Battalion, 5th Field Artillery Unit History. P. 17. at [2] – Retrieved from Internet Archive January 5, 2008.

- Sprague, John T. (2000), The Florida War, By John T. Sprague, Brevet Captain, Eighth Regiment U.S. Infantry, A reproduction of the 1848 edition. University of Tampa Press.

- Sturtevant, William C. (1953) "Chakaika and the 'Spanish Indians': Documentary Sources Compared with the Seminole Tradition." Tequesta. No. 13 (1953):35–73. Found at Chakaika and the "Spanish Indians' Archived February 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Thrapp, Dan L. Encyclopedia of frontier biography, Glendale, California : A.H. Clark Co., 1988–1994. ISBN 978-0-87062-191-8

- U.S. Army National Infantry Museum. Indian wars. at U.S. Army Infantry Home Page – URL retrieved October 22, 2006.

- U.S. Coast Guard Historian's Office publication, "The Coast Guard at War" http://www.uscg.mil/history/articles/h_CGatwar.asp

- Viele, John (1996). The Florida Keys (1st ed.). Sarasota, FL: Pineapple Press. ISBN 1-56164-101-4.

- Vone Research, Inc. Coastal History and Cartography: The Seminole War Period. at Vŏnē Research – URL retrieved November 22, 2010.

- Source notes

- ^ The people, events, and places are real. The dialogue and personalities are the authors, since those could not be recorded in 1835; Afterword chapter p. 265. The author researched Dade's Battle & Pvt. Clark from 1962 until publication in 2008.

Further reading

- Barr, Capt. James (1836). A Correct and Authentic Narrative of the Indian War in Florida: with Description of Maj. Dade's Massacre, and an Account of the Extreme Suffering, for Want of Provisions, of the Army. New York: J. Narine, Printer. Retrieved February 23, 2023.

- Bemrose, John (1966). Reminiscences of the Second Seminole War. Gainesville: University of Florida Press. ISBN 978-0598213884.

- Cohen, Myer M. (An Officer of the Left Wing) (1836). Notices Of Florida and The Campaigns. Charleston, S.C. Burges & Honour, 18 Broad-Street. and New York: B. B. Hussey, 378 Pearl-Street.

- Hovatter, Ryan P. (2021) "Florida Volunteers: Territorial Militia in the Opening of the Second Seminole War" DTIS AD1157347

- Lacey, Michael O., Maj. (2002) Military Commissions: A Historical Survey. The Army Lawyer, March, 2002. Department of the Army Pam. 27–50–350. P. 42. at JAGCNet Portal – URL retrieved October 22, 2006.

- Weisman, Brent Richards. (1999) Unconquered People. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1662-2.

External links

- Maps of North America showing the Second Seminole War (omniatlas.com)

- Buck and Ball at A History of Central Florida Podcast

- Klos, George (1991). "Blacks and Seminoles" (PDF). South Florida History Magazine. No. 2. pp. 12–5. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2017 – via HistoryMiami.