Wentworth Cheswell[a] (11 April 1746 – 8 March 1817) was an American assessor, auditor, Justice of the Peace, teacher and Revolutionary War veteran in Newmarket, New Hampshire. Elected as town constable in 1768, he was elected to other positions, serving in local government every year but one until his death.

Some sources consider Cheswell to be the first African American elected to public office in the history of the United States, as well as the first African American judicial officer.[1] Others are less sure, noting he was biracial and recorded as “white” in censuses.[2][3]

Around the time of his marriage, Wentworth purchased a plot of land from his father Hopestill. His grandfather Richard is believed to be the first African American in New Hampshire to own land. A deed shows that Richard purchased 20 acres (8.1 ha) from the Hilton grant in 1717. In 1801, Wentworth was among the founders of the first library in the town and provided in his will for public access to his personal library.

Wentworth Cheswill | |

|---|---|

| Born | April 11, 1746 |

| Died | March 8, 1817 (aged 70) |

| Burial place | Newmarket, New Hampshire |

| Education | Governor Dummer Academy |

| Occupations | Teacher, soldier, town official |

| Known for | Considered to be first Black man elected to public office in the United States, and first Black judge in the United States |

| Spouse | Mary Davis |

| Children | 13 |

Wentworth Cheswill[a] (April 11, 1746 – March 8, 1817) was an American assessor, auditor, Justice of the Peace, teacher and Revolutionary War soldier in Newmarket, New Hampshire. From 1768 to his death in 1817, he served in local government every year but one.

Some sources consider Cheswill to be the first African American elected to public office in the history of the United States, as well as the first African American judicial officer.[1] Around the time of his marriage, he purchased a plot of land from his father. In 1801, he was among the founders of the first library in the town and provided in his will for public access to his personal library.

Early life and education

Cheswill was the only child born in Newmarket, New Hampshire, to Hopestill Cheswill, a free biracial man whose father had been enslaved or indentured, and his wife, Katherine (Keniston) Cheswill, a white woman. Hopestill Cheswill was a master housewright and carpenter who worked mostly in the thriving city of Portsmouth.[2] He was also a landowner and farmer with part ownership of a sawmill and stream; his prosperity helped provide for his son's education.[3]

Wentworth Cheswill attended Governor Dummer Academy in Byfield, Massachusetts.[4] There he studied with the Harvard graduate Samuel Moody, who taught the classical subjects of Latin and Greek, reading, writing, and arithmetic, as well as swimming and horsemanship.

Early career

After completing his education, Cheswill returned to Newmarket to become a schoolmaster. In 1765, he purchased his first parcel of land from his father. By early 1767, he was an established landowner with more than 30 acres (12 ha) and held a pew in the meetinghouse.[3] By 1770, he owned 114 acres (46 ha).[5] His grandfather Richard is believed to be the first African American in New Hampshire to own land.[6] A deed shows that Richard purchased 20 acres (8.1 ha) from the Hilton grant in 1717.[citation needed]

Cheswill was first elected to public office in 1768 as the town constable, and later was elected to local offices every year (except for 1788) until his death in 1817, to positions such as town selectman, auditor, assessor, and others.[7][5] He is believed to be the first African American elected to public office in the history of the United States. He preceded Alexander Twilight of Vermont (1836), Joseph Hayne Rainey of South Carolina (1870), and John Mercer Langston of Virginia (1888) for the title.[8]

Marriage and family

Cheswill married Mary Davis of Durham on 13 September 1767. Eleven months later, the first of their 13 children was born. Their children were: Paul (1768), Thomas (1770), Samuel (1772), Sarah (1774), Mary (1775), Elizabeth (1778), Nancy (1780), Mehitable (1782), William (1785), a daughter (name unknown) (1785), Martha (1788), a daughter (name unknown) (1792), and Abigail (1792).[9]

His son Thomas Cheswill attended Phillips Exeter Academy and later became a deacon.[citation needed] Thomas' wife and children remained in Newmarket, and are buried in Riverside Cemetery.[5]

Revolutionary War

In April 1776, along with 162 other Newmarket men, Cheswill signed the Association Test.[citation needed] Patriots collected signatures of people opposed to what they considered the hostile actions by the British fleets and armies. The abundance of the returns gave the signers of the Declaration of Independence assurance that their acts would be sanctioned and upheld by most of the colonists.[citation needed]

Cheswill was elected town messenger for the Committee of Safety, which entrusted him to carry news to and from the Provincial Committee at Exeter.[citation needed] In December 1774, people from Portsmouth and surrounding towns, including Newmarket, rallied to defend Fort William and Mary against British reinforcement, in what would later be called the Capture of Fort William and Mary. Cheswill was with the party which built rafts to defend Portsmouth Harbor.[citation needed]

In October 1775, Portsmouth asked for help from neighboring communities and Newmarket voted to send forty-three minutemen. Cheswill rode to Exeter to deliver this information.[2] Cheswill is sometimes credited with participating in Paul Revere's midnight ride although this is not documented in the historical record.[10]

Cheswill served under John Langdon as a private (rank) in a select company called "Langdon's Company of Light Horse Volunteers." Langdon's company made the 250-mile march to Saratoga, New York, to join with the Continental Army under General Horatio Gates, defeating British General John Burgoyne at the Battle of Saratoga, which was the first major American victory in the Revolution.[2] Cheswill's only military service ended 31 October 1777. As with many other men, he served for a limited time, as his family was dependent on him for support.[citation needed]

Local leader

After his service in the war, Cheswill returned to Newmarket and continued his work in town affairs. He also ran a store next to the school house.[11] Cheswill supported his family as a teacher, and was elected and appointed to serve in local government for all but one year of the remainder of his life, as selectman, auditor, assessor, and other roles.[5] In 1778, Cheswill was elected to the convention to draft New Hampshire's first constitution, but he was unable to attend.[2]

He was interested in artifacts from the town. He wrote reports on his fieldwork and he has been called the first archeologist in New Hampshire. The scholars W. Dennis Chesley and Mary B. Mcallister have said, "Cheswell's writings clearly contain the seeds of modern archaeological theory."[12]

In 1801, Cheswill and other men established the first library in Newmarket, the Newmarket Social Library.[9] Of the estates of men who started the library, Cheswill's was valued the highest at over $13,000. In his will he stated,

I also order and direct that my Library and collection of Manuscripts be kept safe and together…if any should desire the use of any of the books and give caution to return the same again in reasonable time, they may be lent out to them, provided that only one book be out of said Library in the hands of any one at the same time.[2]

Cheswill was an unofficial town historian. He copied many of the town records going back as far as the town's incorporation in 1727, including two regional Congregational Church meetings.[5] He collected stories and took notes of town events as they occurred. Jeremy Belknap, who wrote a three-volume History of New Hampshire, quoted Cheswill more than once at length in his work, and credited him for his local histories. They corresponded several times.[citation needed]

In 1805, Cheswill was elected as the Justice of the Peace for Rockingham County, making him the first African-American judge in U.S. history. In that position, he executed deeds, wills, and legal documents. He served as Justice until typhus fever caused his death on 8 March 1817, a month before his 71st birthday.[5]

Legacy

In 1820, shortly after Cheswill died, the New Hampshire Senator David L. Morril used him as a positive example of the contributions of mixed-race persons in a speech to the United States Congress regarding the negative effects of discriminatory racial legislation. Morril opposed a bill to forbid mulatto persons to become citizens of Missouri. In his speech Morril noted,

"In New Hampshire there was a yellow man by the name of Cheswell [sic], who, with his family, were respectable in points of abilities, property and character. He held some of the first offices in the town in which he resided, was appointed Justice of the Peace for that county, and was perfectly competent to perform with ability all the duties of his various offices in the most prompt, accurate, and acceptable manner." Angrily, Morril added, "But this family are forbidden to enter and live in Missouri."[13]

Note: As a mixed-race person, there is little evidence about how Cheswill's racial identification was perceived in his lifetime. He was listed as white on the census (mixed-race was not an option on the census yet),[14] but Morril's reference suggests he was considered mulatto by some contemporaries.[15]

Cheswill is sometimes called the "black Paul Revere,"[16] and his messenger work for the patriot cause in New Hampshire is compared with Paul Revere's midnight ride.[17]

Wentworth's grandfather Richard Cheswill, a former slave of African ancestry, is the first known resident by that surname in New England. PBS Frontline Online discussed the Cheswell family among mixed-race American families in its web feature Blurred Racial Lines of Famous Families, associated with its program Secret Daughter (1996), based on the life and family of producer June Cross.[4]

Some Cheswell descendants, whose families have identified as white for many generations, discovered their connection to the Cheswills and African-American heritage due to publicity in 2002 and following years of research about Wentworth Cheswill done by Rich Alperin, a local resident.[5] In 2006, Cheswell descendants and other New England residents raised funds to restore or replicate the Cheswell gravestones. In addition, they and members of the New Hampshire Old Graveyard Association worked to restore the old Cheswell gravesite.[18]

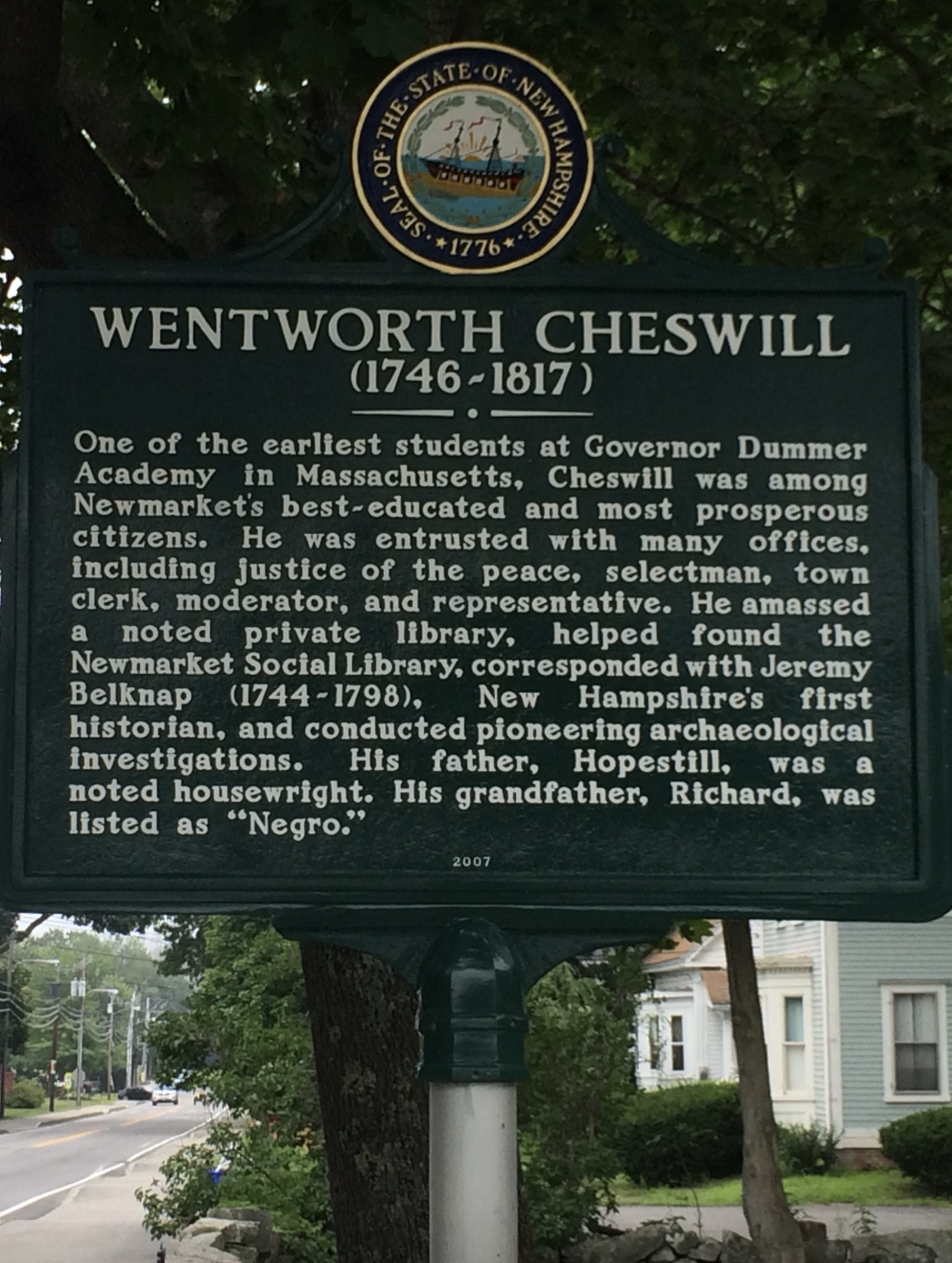

In 2007, a New Hampshire historical marker (number 209) highlighting Wentworth Cheswill's accomplishments was erected at the Cheswill gravesite in Newmarket.[19] There have also been efforts to erect a statue in his honor.[14]

New Hampshire officially celebrated April 11, 2022 (Cheswill's 276th birthday) as "Wentworth Cheswill Day," after a bill sponsored by Representative Charlotte DiLorenzo.[20] DiLorenzo has also sponsored an effort to commission a portrait of Cheswill to be hung in the New Hampshire State House.[21]

Notes

See also

References

- ^ Sauerwein, Daniel (June 28, 2008). "The Real 'Obama before Obama'". History News Network.

- ^ a b c d e Kaplan, Sidney; Kaplan, Emma Nogrady (1989). The Black presence in the era of the American Revolution. Internet Archive. Amherst, Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0-87023-663-1.

- ^ a b Mark J. Sammons and Valerie Cunningham, Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage, (2004), pp. 32-33, accessed 27 July 2009

- ^ a b c Mario de Valdes y Cocom, "Cheswell", The Blurred Racial Lines of Famous Families, PBS Frontline Online, 1996

- ^ a b c d e f g Rachel Grace Toussaint, "Legacy of Newmarket founding father revealed", Seacoast Online, 22 December 2002.

- ^ Plenda, Melanie (April 10, 2023). "The Cheswells: Leave a Legacy of Leadership and Construction". Granite State News Collaborative. Retrieved November 12, 2025.

- ^ Hurley, Sean (August 21, 2020). "In Newmarket, Calls To Put Up Statue Of Black Revolutionary War Hero". www.nhpr.org.

- ^ Sauerwein, Daniel (June 29, 2008). "The Real "Obama before Obama"". HNN. Retrieved October 30, 2025.

- ^ a b "Site No 5 - The Cheswill Cemetery". New Market New Hampshire Historical Society. Retrieved October 22, 2025.

- ^ Landrigan, Leslie (January 1, 2017). "Wentworth Cheswell, the Black Man Who Rode With Revere". New England Historical Society. Retrieved November 13, 2025.

- ^ "Site No 11 - 177 Main St Cheswells Store". New Market New Hampshire Historical Society. Retrieved November 11, 2025.

- ^ W. Dennis Chesley and Mary B. Mcallister, "Pioneers in New Hampshire Archaeology: Wentworth Cheswell Esquire", The New Hampshire Archaeologist, Vol. 22 (1), 1981

- ^ Mark J. Sammons and Valerie Cunningham, Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage, (2004), p. 124, accessed 27 July 2009

- ^ a b "Newmarket Reflects on Legacy of Wentworth Cheswill: Business NH Magazine". www.businessnhmagazine.com. Retrieved November 4, 2025.

- ^ Sammons, Mark; Cunningham, Valerie (2004). Black Portsmouth: Three Centuries of African-American Heritage. UPNE. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-58465-289-2. Retrieved April 29, 2022.

- ^ Hisham, Aqeel. "'Wentworth Cheswill's Ride': Newmarket teacher puts spotlight on life of trailblazer". Portsmouth Herald. Retrieved October 30, 2025.

- ^ "Wentworth Cheswill portrait: Commemorating Black history in the State House • New Hampshire Bulletin". New Hampshire Bulletin. Retrieved October 30, 2025.

- ^ Peg Warner, "Graveyard to get TLC", Seacoast Online, 28 April 2006, hosted at Newmarket, New Hampshire Historical Society

- ^ "Roadside History: Wentworth Cheswill (1746-1817), 'New Hampshire's first historian'". New Hampshire Union Leader. June 4, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2019.

- ^ Whidden, Jenny (July 5, 2021). "Wentworth Cheswill was first African American elected to public office in U.S. history". Concord Monitor. Retrieved October 30, 2025.

- ^ "Wentworth Cheswill portrait: Commemorating Black history in the State House • New Hampshire Bulletin". New Hampshire Bulletin. Retrieved November 11, 2025.

Further reading

- Fitts, James Hill. History of Newfields, NH, Volumes 1 and 2 (1912).

- George, Nellie Palmer. Old Newmarket (1932).

- Getchell, Sylvia (Fitts). The Tide Turns on the Lamprey: A History of Newmarket, NH. (1984).

- Harvey, Joseph. An Unchartered Town: Newmarket on the Lamprey-Historical Notes and Personal Sketches.

- Herman, John, Wentworth Cheswill's Ride: Chasing a Would-Be American Folk Hero. Moonlight Bridge Books, 2024.

- The Granite Monthly. Volume XL, Nos. 2 and 3. New Series, Volume 3, Nos. 2 and 3 (February and March 1908).

- Knoblock, Glenn A. "Strong and Brave Fellows", New Hampshire's Black Soldiers and Sailors of the American Revolution, 1775-1784 (2003).

- Tuveson, Erik R. A People of Color: A Study of Race and Racial Identification in New Hampshire, 1750-1825. Thesis for M.A. in History (May 1995). Available at library of the University of New Hampshire.