The 1811 German Coast uprising was a revolt of black slaves in parts of the Territory of Orleans on January 8–10, 1811. The uprising occurred on the east bank of the Mississippi River in what is now St. John the Baptist, St. Charles and Jefferson Parishes, Louisiana.

| 1811 German Coast uprising | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Slave Revolts in North America | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Black slaves |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Charles Deslondes |

Wade Hampton I John Shaw William C. C. Claiborne | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 200–500 enslaved Africans and African Americans | 2 companies of volunteer militia, 30 regular troops and 40 seamen | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 95 total killed from skirmishes and sentencing after trials | 2 killed | ||||||

| Part of a series on |

| North American slave revolts |

|---|

|

The 1811 German Coast uprising was a slave rebellion which occurred in the Territory of Orleans on January 8–10, 1811. It occurred on the east bank of the Mississippi River in the modern-day Louisiana parishes of St. John the Baptist, St. Charles and Jefferson.[1] The rebellion was the largest of its kind in the history of the United States, but the rebels only killed two white men. Confrontations with U.S. military personnel and local militiamen who were sent to suppress the rebellion, combined with post-trial executions, resulted in the deaths of 95 rebels.

On January 8, between 64 and 125 slaves ignited a fight for freedom and marched from plantations in and near present-day LaPlace, Louisiana on the German Coast towards New Orleans.[2] More people escaped slavery and joined them along the way, and some accounts claimed a total of 200 to 500 people escaped and participated in the rebellion.[3] During their two-day, 20 mi (32 km)-long march the rebels, armed mostly with improvised weapons, burned five plantations along with several sugarhouses and crop fields.[4]

After a few planters were killed and others attacked, White settlers led by U.S. officials formed militia companies. In battle on January 10 they killed 40 to 45 of the people escaping slavery, while suffering no fatalities themselves, then hunted down and killed several other people without trial. Over the next two weeks, White planters and U.S. officials interrogated, tried, executed, and decapitated an additional 44 people escaping slavery who had been captured. Executions were generally by hanging or firing squad. Heads were displayed on pikes to intimidate others.

Since 1995, the African American History Alliance of Louisiana has led an annual commemoration in January of the uprising, in which they have been joined by some descendants of participants in the revolt.[5]

Background

The sugar boom on what was known as Louisiana's German Coast (named for immigrants in the 1720s) began after the American Revolutionary War, while the area near New Orleans was still controlled by Spain. In the 1780s Jean Saint Malo, an escaped slave, established a colony of maroons in the swamps below New Orleans, which eventually led Spanish officials to send militia to capture him. Saint Malo became a folk hero after his execution in New Orleans on June 19, 1784. A decade later, during the height of the French Revolution, Spanish officials discovered a slave conspiracy at Pointe Coupee (established by French settlers around 1720 between Natchez and New Orleans). That slave uprising during the Easter holidays was suppressed before it came to fruition and resulted in 23 executions by hanging (with the severed heads then displayed on the road to New Orleans), and 31 additional slaves were flogged and sent to serve hard labor in other Spanish outposts.[6]

After the Haitian Revolution, planters established similar lucrative sugarcane plantations in the Gulf Coast area, resulting in a dense slave population. They converted from cotton and indigo plantations to sugarcane, so that by 1802, 70 sugar plantations produced over 3,000 tons annually.[7] However, they replicated the brutal conditions, which had led to numerous revolts in Haiti; high profits had been made by working the slaves longer hours and punishing them more brutally, than in other United States territory, so that the slaves lived shorter lives than any other slave society in North America.[8] Some accounts claimed blacks outnumbered whites by nearly five to one by 1810, and about 90% of whites in the area enslaved people. More than half of those enslaved may have been born outside Louisiana, many in Africa, where various European nations established slave trading outposts and Kongo was ripped apart by civil wars.[9]

After the U.S. negotiated the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, both the Marquis de Lafayette and James Monroe declined to become the governor of the Territory of Orleans. President Thomas Jefferson then turned to a fellow Virginian, William C. C. Claiborne, whom he appointed on an interim basis and who arrived in New Orleans with 350 volunteers and 18 boats. Claiborne struggled with the area's diverse population, particularly because he spoke neither French nor Spanish. The population also included a larger proportion of native Africans among the slaves than elsewhere in the U.S. In addition, the mixed-race Creole and French-speaking population grew markedly with refugees from Haiti (and their slaves) following the successful Haitian Revolution. Claiborne was not used to a society with the number of free people of color that Louisiana had, but he worked to continue their role in the militia that had been established under Spanish rule.

Long-term French Creole residents complained to Washington, D.C., about Claiborne and new U.S. settlers in the territory, and wanted no part of President Jefferson's plan to pay 30,000 Americans to move into the new territory and amalgamate with the residents. Thus, by 1805, a delegation led by Jean Noël Destréhan went to Washington to complain about the "oppressive and degrading" form of the territorial government, but President Madison continued to support Claiborne, who had expressed great doubts about the planters' honesty and trustworthiness.[10] Lastly, Claiborne suspected that the Spanish in nearby West Florida might encourage an insurrection. Thus, he struggled to establish and maintain his authority.

In the overall Territory of Orleans, from 1803 to 1811, the free black population nearly tripled, to 5,000, with 3,000 arriving as migrants from Haiti (via Cuba) in 1809–1810. In Saint-Domingue they had enjoyed certain rights as gens de couleur, including owning slaves themselves.[11] Furthermore, between 1790 and 1810, slave traders brought around 20,000 enslaved Africans to New Orleans.[12] The masters and slaves were virtually all Catholic.[13]

The waterways and bayous around New Orleans and Lake Pontchartrain made transportation and trade possible but also provided easy escapes and nearly impenetrable hiding places for runaway slaves. Some maroon colonies continued for years within several miles of New Orleans. With the spread of ideas of freedom from the French and Haitian Revolutions, European Americans worried about slave uprisings, particularly in the Louisiana area. In 1805, they heard a traveling Frenchman was preaching about liberty, equality, and fraternity to the French-speaking slaves, and arrested him as dangerous.[14]

Uprising

Beginning

A group of slaves met on January 6, 1811.[15] It was a period when work had relaxed on the plantations after the fierce weeks of the sugar harvest and processing. As planter James Brown testified weeks later, "The black Quamana [Kwamena, meaning "born on Saturday"], owned by Mr. Brown, and the mulatto Harry, owned by Messrs. Kenner and Henderson, were at the home of Manuel Andry on the night of Saturday–Sunday of the current month in order to deliberate with the mulatto Charles Deslondes, chief of the brigands."[citation needed] Slaves had spread word of the planned uprising among the slaves at plantations up and down the German Coast.

The revolt began on January 8 at the Andry plantation.[16] After striking and badly wounding Andry, the slaves killed his son Gilbert. "An attempt was made to assassinate me by the stroke of an axe", Andry wrote. "My poor son has been ferociously murdered by a horde of brigands who from my plantation to that of Mr. Fortier have committed every kind of mischief and excesses, which can be expected from a gang of atrocious bandittis of that nature."[17]

Escalation

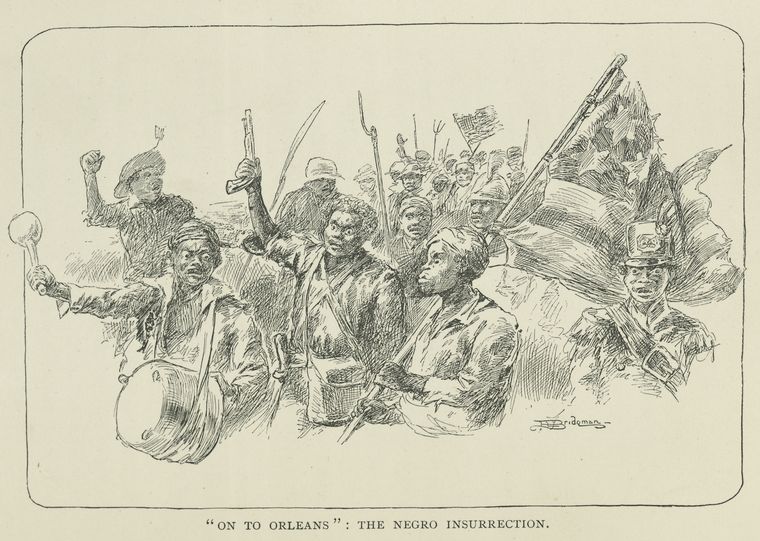

The rebellion gained momentum quickly. The approximately 15 slaves at Andry's plantation, about 30 miles (50 km) upriver from New Orleans, joined another eight slaves from the next-door plantation of the widows of Jacques and Georges Deslondes. This was the home plantation of Charles Deslondes, a slave driver (a slave overseer of other slaves) later described by one of the captured slaves as the "principal chief of the brigands". Small groups of slaves joined from every plantation the rebels passed. Witnesses remarked on their organized march. They carried mostly pikes, hoes, and axes, but few firearms, and they marched to drums while some carried flags.[4] Approximately 10–25% of any given plantation's slave population joined with them.

At the plantation of James Brown, Kook, one of the most active participants and key figures in the story of the uprising, joined the insurrection. At the next plantation down, Kook attacked and killed François Trépagnier with an axe.[18] He was the second and last planter killed in the rebellion. After the band of slaves passed the LaBranche plantation, they stopped at the home of the local physician. Finding him gone, Kook set his house on fire.

Some planters testified at the trials in parish courts that they were warned by slaves of the uprising. Others regularly stayed in New Orleans, where many had town houses,[19] and trusted their plantations to overseers to run. Planters quickly crossed the Mississippi River to escape the insurrection and to raise a militia.

As those escaping moved downriver, they passed larger plantations, from which other slaves joined them. Numerous slaves joined the insurrection from the Meuillion plantation, the largest and wealthiest plantation on the German Coast. The rebels laid waste to Meuillion's house. They tried to set it on fire, but a slave named Bazile fought the fire and saved the house.

After nightfall the escaping slaves reached Cannes-Brulées, about 15 miles (24 km) northwest of New Orleans. The men had traveled between 14 and 22 miles (23 and 35 km), a march that probably took them seven to ten hours. By some accounts, they numbered "some 200 slaves", although other accounts estimated up to 500.[20] As typical of revolts of most classes, free or slave, the insurgent slaves were mostly young men between the ages of 20 and 30. They represented primarily lower-skilled occupations on the sugar plantations, where slaves labored in difficult conditions with a low life expectancy.

Suppression

Despite his injuries, Andry crossed the river and made contact with other planters, raising a militia and pursuing the escaping slaves. By noon on January 9, the residents of New Orleans had heard about the insurrection. By sunset, General Wade Hampton I, Commodore John Shaw, and Claiborne sent two volunteer militia companies, 30 US Army soldiers, and 40 US Navy sailors to fight the escaping slaves. By about 4 a.m. on January 10, this force had reached Jacques Fortier's plantation, where Hampton thought the escaped slaves had encamped overnight.

However, the escaped slaves had started back upriver about two hours earlier, had traveled about 15 miles (24 km) back up the coast, and had neared Bernard Bernoudy's plantation. There, planter Charles Perret, in cooperation with Andry and Judge St. Martin, had assembled a militia of about 80 men from the river's opposite side. At about 9 o'clock, this militia force discovered escaping slaves moving toward high ground on Bernoudy's plantation. Perret ordered his men to attack the escaping slaves, which he later wrote numbered about 200 men, about half on horseback. (Most accounts said only the leaders were mounted, and historians believe it unlikely the escaping men could have gathered so many mounts.) Within a half-hour, 40 to 45 escaping people had been killed; the remainder slipped away into the woods and swamps. Perret's and Andry's militias tried to pursue them despite the difficult terrain.

On January 11, the militia, assisted by Native American trackers as well as hunting dogs, captured Deslondes, whom Andry considered "the principal leader of the bandits." A slave driver and son of a white man and a slave, Deslondes received no trial or interrogation. The naval officer Samuel Hambleton described his execution as having his hands chopped off, "then shot in one thigh & then the other, until they were both broken – then shot in the Body and before he had expired was put into a bundle of straw and roasted!"[21] His cries under the torture could intimidate other escaped slaves in the marshes.

The following day Pierre Griffee and Hans Wimprenn, who were thought the murderers of M. Thomassin and M. François Trépagnier, were captured, killed, and their heads decapitated for delivery to the Andry estate. Major Milton and the dragoons from Baton Rouge arrived and provided support for the militia, since Hampton believed them supported by Spanish authorities in West Florida.[22]

Aftermath

Trials

Having suppressed the insurrection, the planters and government officials continued to search for people who had escaped. Those captured later were interrogated and jailed before trials. Officials convened three tribunals: one at Destrehan Plantation in St. Charles Parish, one in St. John the Baptist Parish, and the third in New Orleans (Orleans Parish).

The Destrehan trials, overseen by Judge Pierre Bauchet St. Martin, resulted in the execution of 18 of 21 captured people by firing squad.[23][24] Some slaves testified against others, but others refused to testify or submit to the all-planter tribunal.

In New Orleans, Commodore Shaw presumed that "but few of those who have been taken were acquitted." The New Orleans trials resulted in the conviction and summary executions of 11 more slaves. Three were publicly hanged in the Place d'Armes, now Jackson Square. One of those spared was a 13-year-old boy, who was ordered to witness another man's death and then received 30 lashes. Another escaped person was treated with leniency because his uncle turned him in and begged for mercy. The sentence of a third person was commuted because of the valuable information he had given.[25]

The heads of those executed were put on pikes and the mutilated bodies of dead rebels displayed to intimidate other slaves. By the end of January, nearly 100 heads were displayed on the levee from the Place d'Armes in central New Orleans along the River Road to the plantation district and Andry's plantation, nearly quadrupling the number of heads nailed to posts from New Orleans to Pointe Coupee after the 1795 slave uprising.[26] The naval officer Samuel Hambleton described the heads posted on stakes that lined the levee as follows, "They were brung up here for the sake of their Heads, which decorate our Levee, all the way up the coast. I am told they look like crows sitting on long poles."[27]

U.S. territorial law provided no appeal from a parish court's ruling, even in cases involving imposition of a death sentence on a slave. Governor Claiborne, recognizing that fact, wrote[28] to the judges of each court that he was willing to extend executive clemency ("in all cases where circumstances suggest the exercise of mercy a recommendation to that effect from the Court and Jury, will induce the Governor to extend to the convict a pardon."). In fact, Claiborne did commute two death sentences, those of Henry[29] and Theodore,[30] each referred by the Orleans Parish court.[31] No record has been found of any referral from the court in St. Charles Parish, or of any refusal by the governor of an application for clemency.

Outcome

Militias killed about 95 slaves between the battle, subsequent summary apprehensions and executions, as well as by execution after trials.[19] From the trial records, most of the leaders appeared to have been mixed-race Creoles or mulattoes, although numerous slaves were native-born Africans.[9] Fifty-six of the slaves captured on January 10 and involved in the revolt were returned to their masters, who may have punished them but wanted their valuable laborers back to work. Thirty more escaping slaves were captured and returned to their masters after planters determined they had been forced to join the revolt by Deslondes and his men.[19]

The heirs of Meuillon petitioned the legislature for permission to free the mulatto slave Bazile, who had worked to preserve his master's plantation. Not all the slaves supported insurrection, knowing the trouble it could bring and not wanting to see their homes and communities destroyed.[32] The uprising was short-lived and quickly crushed by local authorities.[20] Showing planter influence, the legislature of the Territory of Orleans approved compensation of $300 to planters for each escaping slave killed or executed. The territory gratefully accepted the presence of U.S. troops after the revolt. The national press covered the insurrection, with some Northerners seeing it arising out of the wrongs suffered under slavery.[33]

Legacy

The uprising started in present-day LaPlace and followed a 20-mile trek on the old River Road through the present-day towns of Montz, Norco, New Sarpy, Destrehan, St. Rose and ended at much of what had once been the Kenner and Henderson Plantations and is now Rivertown and Louis Armstrong International Airport in Kenner.

While the Destrehan Plantation tour concentrates on architecture and white lifestyle and family histories, a small museum in a converted slave cabin (not on the standard tour) features folk paintings of the 1811 uprising.[34] Louisiana's historical marker for the former Andry plantation mentions "Major 1811 slave uprising organized here."[35] The Whitney Plantation, in St. John the Baptist Parish, opened in 2014 and is the first plantation museum in the country dedicated to the slave experience. The Whitney Plantation includes a memorial and information to commemorate the 1811 Slave Uprising of the German Coast.

Despite its size and connection to the French and Haitian revolutions, the rebellion is not thoroughly covered in history books. As late as 1923, however, older black men "still relate[d] the story of the slave insurrection of 1811 as they heard it from their grandfathers."[36] Since 1995, the African American History Alliance of Louisiana has led an annual commemoration at Norco in January, where they have been joined by some descendants of members of the revolt.[5]

In 2015, artist Dread Scott began organizing a massive re-enactment of the uprising;[37] the 26 mile, 2-day event took place in November 2019.[38][39] The uprising is featured in Talene Monahon's 2020 play about historical reenactment, How to Load a Musket.[40] In 2021, the 1811 Kid Ory Historic House opened on the site of Woodland Plantation in LaPlace, which is in the National Register of Historic Places of the United States. The museum is dedicated to the German Coast uprising and to Kid Ory, an American jazz composer, trombonist, and bandleader born there in 1886.[41][42]

See also

- History of slavery in Louisiana

- List of incidents of civil unrest in the United States

- St. John the Baptist Parish

- Sugar industry of the United States § History

References

- ^ Rothman (2005), p. 106.

- ^ Sternberg, Mary Ann (2001). Along the River Road: Past and Present on Louisiana's Historic Byways. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press. p. 12.

- ^ "'American Rising': When Slaves Attacked New Orleans". NPR. January 16, 2011. Retrieved January 16, 2011.

- ^ a b Genovese, Eugene D. (1976). Roll, Jordan, Roll: The World the Slaves Made. New York: Vintage Books. p. 592.

- ^ a b Lowen, James W. (2007). Lies Across America: What Our History Sites Get Wrong. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 192.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), pp. 88–90.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 47.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 49.

- ^ a b Rothman (2005), p. 111.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), pp. 52–58.

- ^ Buman, Nathan A. (August 2008). "To Kill Whites: The 1811 Louisiana Slave Insurrection" (PDF). Louisiana State University. pp. 32–33, 37, 51, 58. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 4, 2016. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 90.

- ^ "The Role of Slaves and Free People of Color in the History of St. Charles Parish". St. Charles Parish, Louisiana Virtual History Museum. March 27, 2019. Retrieved September 17, 2021.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), pp. 89–90.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 11.

- ^ Andry, Manuel (April 21, 2017). "Dictionary of Louisiana Biography". Archived from the original on April 21, 2017. Retrieved April 15, 2017.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 135.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 109.

- ^ a b c "January 8, 1811". African American Registry. 2005. Archived from the original on October 1, 2009. Retrieved December 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Kolchin, Peter (1994). American Slavery: 1619–1877. New York: Hill and Wang. p. 156.[ISBN missing]

- ^ Smith, T. R. (2011). Southern Queen: New Orleans in the Nineteenth Century. Bloomsbury Academic. p. 31. ISBN 978-1847251930. Retrieved April 6, 2015.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), pp. 142–43.

- ^ "Jean Noël Destrehan" Archived April 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine by John H. Lawrence, KnowLouisiana.org Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Ed. David Johnson. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities, 18 Jun 2013. Web. 15 Apr 2017.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 156.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), p. 148.

- ^ Rasmussen pp. 148–50

- ^ Smith, Clint (2021). "The Louisiana Rebellion". In Kendi, Ibram X.; Blain, Keisha N. (eds.). Four Hundred Souls: A Community History of African America, 1619–2019. New York: One World. pp. 173–176. ISBN 9780593134047.

- ^ January 16, 1811, and January 19, 1811, Rowland, Dunbar, ed. Official Letter Books of WCC Claiborne, 1801–1816. Vol. 5. State department of archives and history, 1917, pp. 100–01, 107–08.

- ^ Carter, 1940, p. 983

- ^ Carter, 1940, p. 982; Rowland, pp. 198–99

- ^ Eaton, Fernin (November 7, 2011). "Slave Uprising; Governor on Trial: Claiborne in His Own Words". Salon publique, Pitot House, New Orleans. Academia.edu. Retrieved February 19, 2015

- ^ Rothman (2005), p. 115.

- ^ Rothman (2005), p. 116.

- ^ Rasmussen (2011), pp. 199–201.

- ^ Marael Johnson, Louisiana, Why Stop?: A Guide to Louisiana's Roadside Historical Markers, Houston: Gulf Publishing Co., 1996, p. 52. [ISBN missing]

- ^ Lubin F. Laurent, "A History of St. John the Baptist Parish", Louisiana Historical Quarterly, 7 (1924), pp. 324–25.

- ^ Boucher, Brian (September 29, 2015). "Dread Scott Stages Slave Uprising". Artnet News. Retrieved September 6, 2017.

- ^ Fadel, Leila; Bowman, Emma (November 9, 2019). "Hundreds March In Reenactment Of A Historic, But Long Forgotten Slave Rebellion". NPR. Retrieved November 12, 2021.

- ^ Rojas, Rick (November 11, 2019). "A Slave Rebellion Rises Again: Some 500 slaves revolted in Louisiana but were largely ignored by history. Two centuries later, an ambitious re-enactment brings their uprising back to life". New York Times. p. A18. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Soloski, Alexis (January 16, 2020). "'How to Load a Musket' Review: A Play About Re-enactors Gets Real". New York Times. Retrieved January 20, 2020.

- ^ "1811 Kid Ory Historic House". 1811 Kid Ory Historic House. 2021. Archived from the original on January 15, 2022. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Kennon, Alexandra (May 24, 2021). "The Kid Ory House: From Jazz to the 1811 Slave Revolt, LaPlace's new museum explores a broad scope of Southern history". Country Roads. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

Bibliography

Letters

- "John Shaw to Paul Hamilton", New Orleans, January 18, 1811, National Archives.

- "Samuel Hambleton to David Porter", January 15, 1811, Papers of David Porter, Library of Congress, in Slavery, Stanley Engerman, Seymour Drescher, and Robert Paquette, eds. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. p. 326.

Books

- Aptheker, Herbert (1943). American Negro Slave Revolts. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0717806057.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - Carter, Clarence Edwin, ed. The Territorial Papers of the United States, V. 9: The Territory of Orleans – 1803–1812. U.S. Government Printing Office, 1940, p. 983.

- Conrad, Glenn R. ed. The German Coast: Abstracts of the Civil Records of St. Charles and St. John the Baptist Parishes, 1804–1812. Lafayette: Center for Louisiana Studies, 1981. [ISBN missing]

- Engerman, Stanley, Seymour Drescher, and Robert Paquette, eds. Slavery. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001. pp. 324–26. ISBN 0192893025.

- "German Coast Uprising (1811)", in Junius P. Rodriguez, ed., The Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Westport, Connecticut, and London: Greenwood Press, 2007, 213–16. ISBN 0313332711.

- Rasmussen, Daniel (2011). American Uprising: The Untold Story of America's Largest Slave Revolt. New York: Harper. ISBN 978-0061995224.

- Rothman, Adam (2005). Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674024168.

- Sitterson, J. Carlyle. Sugar Country; the Cane Sugar Industry in the South, 1753–1950. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1953. ISBN 0837170273.

- Thrasher, Albert, ed. On to New Orleans! Louisiana's Heroic 1811 Slave Revolt. 2nd ed. New Orleans: Cypress Press, 1996. ISBN 0964459507.

External links

- "Slave Insurrection of 1811" in Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities (LEH)'s 64 Parishes Encyclopedia (2011)

- "Reenacting the German Coast Uprising" in LEH's 64 Parishes Encyclopedia (2019)

- "Slaves Rebel in Louisiana" at African American Registry

- Daniel Rasmussen discussing his book about America's largest slave revolt on YouTube (2012)

- 200-year commemoration of the revolt; with photo of historic marker at The Times-Picayune (2011)