The Blemmyes were an Eastern Desert people who appeared in written sources from the 7th century BC until the 8th century AD. By the late 4th century, they had occupied Lower Nubia and established a kingdom. From inscriptions in the temple of Isis at Philae, a considerable amount is known about the structure of the Blemmyan state.

The Blemmyes are usually identified as one of the components of the archaeological X-Group culture that flourished in Late Antiquity. Their identification with the Beja people who have inhabited the same region since the Middle Ages is generally accepted.

The Blemmyes (Ancient Greek: Βλέμμυες or Βλέμυες, Blémues [blé.my.es], Latin: Blemmyae) were an Eastern Desert people who appeared in written sources from the 7th century BC until the 8th century AD.[1] By the late 4th century, they had occupied Lower Nubia and established a kingdom. From inscriptions in the temple of Isis at Philae, a considerable amount is known about the structure of the Blemmyan state.[2]

The Blemmyes are usually identified as one of the components of the archaeological X-Group culture that flourished in Late Antiquity.[1] Their identification with the Beja people who have inhabited the same region since the Middle Ages is generally accepted.[3][4]

Origins

Around 1000 BC a group of people, referred to by archeologists as C-group, migrated from Lower Nubia (the area between present-day Aswan and Wadi Halfa) and settled in Upper Nubia (the Nile Valley north of Dongola in Sudan), where they developed the kingdom of Napata from about 750 BC. For some time this kingdom controlled Egypt too, supplying its 25th Dynasty. Contemporary with them are the archaeological remains of another cultural group, the "pan-grave people." They have been identified with the Medjay of written sources.[5] Sites related to them have been found at Khor Arba'at and Erkowit in the heartland of present-day Beja.[6] The evidence suggests that only a minority of "the pan-grave people" lived in the Nile Valley, where they existed in small enclave communities among the Egyptians and C-group populations, being periodically used as desert scouts, warriors or mine workers.[5] The majority were probably desert nomads, breeding donkeys, sheep and goats. After 600 BC, the Napatan, C-group dynasty lost control over Egypt as well as the then-rather desolate Lower Nubia. The latter area subsequently remained more or less without permanent settlements for four centuries. The main explanation for the hiatus of sedentary population in Lower Nubia has been the drying up of this part of the world,[7] making river valley agriculture difficult. Due to climatic change, the level of the Nile had been lowered to a degree which could only be compensated for at the beginning of the first century AD, when the saqiyah waterwheel was developed.[8] Until then, the area was only sparsely populated by desert nomads. Politically, it was "a sort of no-man's land where caravans, unless they were provided with considerable escort, were delivered to brigands".[9]

Etymology

An etymology first proposed by Joseph Halévy connects the name Blemmyes with the modern Beja term bálami "desert inhabitant, nomad", derived from bal "desert".[10]

History

The people referred to in Greek texts as Blemmyes may have their earliest mention as Egyptian Bwrꜣhꜣyw in the Kushite enthronement stela of Anlamani from Kawa from the late seventh century BC. The representation Brhrm in a petition from El Hiba one century later may reflect the same root term. Similar terms recur in Egyptian sources from later centuries with more certain correspondence to the Greek etymon of Blemmyes.[11] In Coptic, Ⲃⲁⲗⲛⲉⲙⲙⲱⲟⲩⲓ, Balnemmōui, is widely accepted as equivalent to Greek Βλέμμυης, Blémmuēs.[12]

The Greek term first appears in the third century BC in one of the poems of Theocritus and in Eratosthenes, who is cited in Strabo's Geographica (first century AD).[3][13] Eratosthenes described the Blemmyes as living with the Megabaroi in the land between the Nile and the Red Sea north of Meroë. Strabo himself, locating them south of Syene (Aswan), describes them as nomadic raiders but not bellicose. In later writings, the Blemmyes are described in stereotypical terms as barbarians living south of Egypt. Pomponius Mela and Pliny the Elder described them as headless beings with their faces on their chests.[3]

The cultural and military power of the Blemmyes started to grow to such a level that in 193, Pescennius Niger asked a Blemmye king of Thebes to help him in the battle against the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus.[citation needed] In 250, the Roman Emperor Decius put in much effort to defeat an invading army of Blemmyes.[14] A few years later, in 253, they attacked Upper Egypt (Thebaid) again but were quickly defeated. In 265, they were defeated again by the Roman Prefect Firmus, who later in 273 would rebel against the Empire and the Queen of the Palmyrene Empire, Zenobia, with the help of the Blemmyes themselves. The Blemmyes were said to have joined forces with the Palmyrans against the Romans in the battle of Palmyra in 273.[14]

The Roman general Marcus Aurelius Probus took some time to defeat the usurpers with his allies but could not prevent the occupation of Thebais by the Blemmyes. That meant another war and almost an entire destruction of the Blemmyes army (279–280).[14][15][16]

During the reign of Diocletian, the province of Upper Aegyptus, Thebaid, was again occupied by the Blemmyes. In 298, Diocletian made peace with the Nobatae and Blemmyes tribes, agreeing that Rome would move its borders north to Philae (South Egypt, south of Aswan) and pay the two tribes an annual gold stipend.[17][14]

Language

Multiple researchers have proposed that the language of the Blemmyes was an ancestor of modern Beja.[18][19][20][21] Nubiologist Gerald M. Browne and linguist Klaus Wedekind have both attempted to demonstrate that the language of an ostracon found in Saqqara is an ancestor of Beja, and were both of the opinion that it represented a fragment of Psalm 30.[22][23][24]

Culture

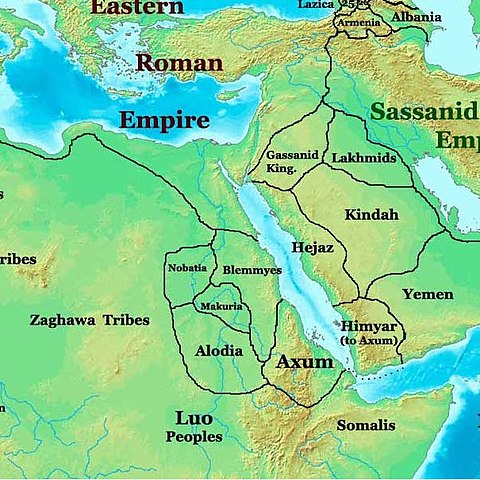

The Blemmyes occupied a considerable region in what is modern day Sudan. There were several important cities such as Faras, Kalabsha, Ballana, and Aniba. All were fortified with walls and towers of a mixture of Egyptian, Hellenic, Roman, and Nubian elements.

Kalabsha would serve as the capital of the Blemmyes.[25] The Blemmyes culture was also influenced by the Meroitic culture, and their religion was centered in the temples of Kalabsha and Philae. The former edifice was a huge local architectural masterpiece, where a solar, lion-like divinity named Mandulis was worshipped. Philae was a place of mass pilgrimage, with temples to Isis, Mandulis, and Anhur. It was where the Roman Emperors Augustus and Trajan made many contributions with new temples, plazas, and monumental works.[26]

Religion

Most of our information on Blemmye religious practices comes from inscriptions in the temples of Philae and Kalabsha, and from Roman and Egyptian accounts of the worship of Isis at Philae. Mandulis was worshipped at Kalabsha. Additional cult societies were dedicated to the gods Abene, Amati, and Khopan.[27] According to Procopius, the Blemmyes also worshipped Osiris and Priapus. Procopius also alleges that the Blemmyes made human sacrifices to the sun.[28]

Letters from Gebelein from the early sixth century suggest that some portion of the Blemmye population had converted to Christianity.[29]

Blemmyan kingdom

Both Blemmye inscriptions in Greek and records from Greeks and Romans refer to the Blemmyes as having βασιλισκοι and βασιλῆς, which terms usually refer to kings. Because of this, the Blemmyes are often described as having had a kingdom. Some historians are skeptical: László Török writes that "the term should not be interpreted narrowly, it is doubtful that there ever existed one centralised Blemmyan kingdom; more likely there were several tribal 'states' developing towards some sort of hierarchical unity".[30]

Blemmye writings mention various royal officials who seemed to be arranged in a hierarchy. Beneath the kings were phylarchs, who were chiefs of separate tribes. Other officials include sub-chiefs, court officials, and scribes. The Blemmyes kings had the power to levy taxes and grant exemptions as well as authority over the territory.

From the historical record, the following Blemmye kings are known:[31]

- Tamal (early 4th or 5th century)

- Isemne

- Degou

- Phonen (c. 450)

- Pokatimne

- Kharakhen

- Barakhia

References

- ^ a b Christides, Vassilios (1980). "Ethnic Movements in Southern Egypt and Northern Sudan: Blemmyes-Beja in Late Antique and Early Arab Egypt until 707 A. D.". Listy filologické. 103 (3): 129–143. JSTOR 23464092.

- ^ Welsby, Derek (2002), The Medieval Kingdoms of Nubia: Pagans, Christians and Muslims Along the Middle Nile, British Museum, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b c Dijkstra, Jitse H.F. (2013), "Blemmyes", The Encyclopedia of Ancient History, Wiley, pp. 1145–1146.

- ^ Dijkstra, Jitse H.F. (2018), "Blemmyes", The Oxford Dictionary of Late Antiquity, vol. 1, Oxford University Press, p. 253.

- ^ a b Bietak 1986: 17 f.

- ^ Arkell 1955: 78.

- ^ Bietak 1986: 18-19.

- ^ Carlsson and Van Gerven 1979: 55.

- ^ Dahl, Gudrun (2006). "Precolonial Beja: A Periphery at the Crossroads" (PDF). njas.helsinki. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2007-06-10.

- ^ Zahorski, Andrzej (1987). "Reinisch and some problems of the study of Beja today". In Mukarovsky, Hans. G. (ed.). Leo Reinisch: Werk und Erbe (in German). Vol. 42. Vienna: Austrian Academy of Sciences. p. 130. doi:10.1515/stuf-1989-0523. ISBN 3700111495.

- ^ Barnard, Hans (2005). "Sire, il n'y a pas de Blemmyes: A Re-Evaluation of Historical and Archaeological Data". In Starkey, Janet (ed.). People of the Red Sea: Proceedings of Red Sea Project II Held in the British Museum October 2004. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 23–40. ISBN 1-84171-833-5.

- ^ Eide, Tormod; Hägg, Tomas; Pierce, Richard Holton; Török, László, eds. (1998). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum, Vol. III: From the First to the Sixth Century AD. Bergen: Institutt for klassisk filologi, russisk og religionsvitenskap, Seksjon for gresk, latin og egyptologi, Universitetet i Bergen. p. 1108. ISBN 82-91626-07-3.

- ^ Eide, Tormod; Hägg, Tomas; Pierce, Richard Holton; Török, László, eds. (1996). Fontes Historia Nubiorum, Vol. II: From the Mid-Fifth to the First Century BC. Bergen: Institutt for klassik filologi, russisk og religionsvitenskap, Seksjon for gresk, latin og egyptologi, Universitetet i Bergen. pp. 560, 569. ISBN 82-91626-01-4.

- ^ a b c d Morkot, Robert G. (2010-06-07). The A to Z of Ancient Egyptian Warfare. Scarecrow Press. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4616-7170-1.

- ^ Burckhardt, Jacob (2018-12-14). The Age of Constantine the Great (1949). Routledge. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-429-87021-7.

- ^ Hrozný, Bedrǐch (1970). Archiv Orientální.

- ^ According to Diocletian#Conflict in the Balkans and Egypt version 23 September 2011.

- ^ Quibell, J.E. (1909). Excavations at Saqqara (1907–1908). Cairo: L'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. p. 109.

- ^ Satzinger, Helmut (1992). "Die Personennamen von Blemmyern in koptischen und griechischen Texten: orthographische und phonetische Analyse". In Ebermann, E.; Sommerauer, E.R.; Thomanek, K.E. (eds.). Komparative Afrikanistik. Sprach-, geschichts- und literaturwissenschaftliche Aufsätze zu Ehren von Hans G. Mukarovsky anlässlich seines 70. Geburtstags (in German). Vienna: Afro-Pub. pp. 313–324. ISBN 3850430618.

- ^ Satzinger, Helmut (2012). The Barbarian Names on the Ostraca from the Eastern Desert (3rd Century CE). 'Inside and Out: Interactions between Rome and the Peoples on the Arabian and Egyptian Frontiers in Late Antiquity (200–800 CE). Ottawa.

- ^ Rilly, Claude (2019). "Languages of Ancient Nubia". In Raue, Dietrich (ed.). Handbook of Ancient Nubia. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 133–134. ISBN 978-3-11-041669-5.

- ^ Browne, Gerald (2003). Textus Blemmyicus aetatis christianae. Champaign.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Browne, Gerald (March 2004). "Blemmyes and Beja". The Classical Review. 54 (1): 226–228. doi:10.1093/cr/54.1.226.

- ^ Wedekind, Klaus (2010). "More on the Ostracon of Browne's Textus Blemmyicus". Annali: Dipartimento Asia, Africa e Mediterraneo, Sezione Orientale. 70: 73–81.

- ^ Engstrom, Barbie (1984). Egypt and a Nile Cruise. Kurios Press. ISBN 978-0-916588-05-2.

- ^ Regula, DeTraci (1995). The mysteries of Isis: her worship and magick (1st ed.). St. Paul, Minn.: Llewellyn. ISBN 1-56718-560-6. OCLC 33079651.

- ^ Eide, Tormod; Hägg, Tomas; Pierce, Richard Holton; Török, László, eds. (1998). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD, vol. III: From the First to the Sixth Century AD. Bergen: University of Bergen. pp. 1132–1138. ISBN 82-91626-07-3.

- ^ Eide, Tormod; Hägg, Tomas; Pierce, Richard Holton; Török, László, eds. (1998). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD, vol. III: From the First to the Sixth Century AD. Bergen: University of Bergen. p. 1191. ISBN 82-91626-07-3.

- ^ Eide, Tormod; Hägg, Tomas; Pierce, Richard Holton; Török, László, eds. (1998). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD, vol. III: From the First to the Sixth Century AD. Bergen: University of Bergen. pp. 1196–1216. ISBN 82-91626-07-3.

- ^ Eide, Tormod; Hägg, Tomas; Pierce, Richard Holton; Török, László, eds. (1998). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD, vol. III: From the First to the Sixth Century AD. Bergen: University of Bergen. p. 1087. ISBN 82-91626-07-3.

- ^ Eide, Tormod; Hägg, Tomas; Pierce, Richard Holton; Török, László, eds. (1998). Fontes Historiae Nubiorum: Textual Sources for the History of the Middle Nile Region between the Eighth Century BC and the Sixth Century AD, vol. III: From the First to the Sixth Century AD. Bergen: University of Bergen. pp. 1131, 1198. ISBN 82-91626-07-3.