Allensworth is an unincorporated community in Tulare County, California.[2] Established by Allen Allensworth in 1908, the town was the first in California to be founded, financed, and governed by African-Americans.

Allensworth sits at an elevation of 213 feet (65 m),[2] the same elevation as the huge and historically important Tulare Lake shore when it was full.[4] The community is located in the ZIP Code 93219 and in the area code 661.

HistoryEdit

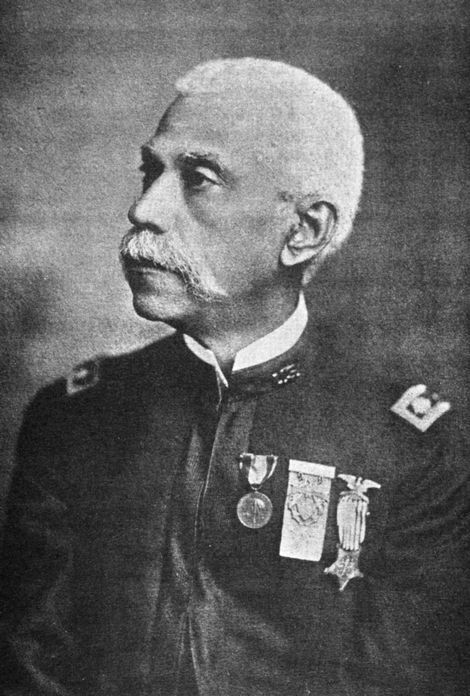

On June 30, 1908, clergyman Colonel Allen Allensworth and Denison University graduate Professor William Alexander Payne[5][6] established the California Colony and Home Promoting Association.[6] Allensworth and Payne were the chief officers, with the other constituents being miner John W. Palmer; minister William H. Peck; and real estate agent Harry A. Mitchell (all of whom were Black men).[6] The Association purchased 20 acres of land from the Pacific Farming Company with the goal of establishing a town for Black soldiers. The land was situated at the then-extant Santa Fe rail line stop, titled “Solita.”[3] The land was divided into individual parcels,[7][3] forming “a colony of orderly and industrious African Americans who could control their own destiny.”[8]

Allensworth, California | |

|---|---|

Allensworth's restored buildings now occupy Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park. | |

Location in Tulare County and the state of California | |

| Coordinates: 35°51′00″N 119°23′21″W / 35.85000°N 119.38917°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Tulare |

| Founded | 1908 |

| Named after | Allen Allensworth |

| Area | |

• Total | 3.10 sq mi (8.04 km2) |

| • Land | 3.10 sq mi (8.04 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0.00 km2) 0% |

| Elevation | 213 ft (65 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 531 |

| • Density | 171.2/sq mi (66.09/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-8 (Pacific (PST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-7 (PDT) |

| ZIP code | 93219 |

| Area code | 661 |

| FIPS code | 06-01010 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2585402 |

Allensworth is an unincorporated community in Tulare County, California.[2] Established by Allen Allensworth in 1908, the town was the first in California to be founded, financed, and governed by African-Americans.[3]

The original townsite is designated as Colonel Allensworth State Historic Park. The 2020 United States census reported Allensworth's population was 531, up from 471 at the 2010 census. For statistical purposes, the United States Census Bureau has defined Allensworth as a census-designated place (CDP).

Allensworth sits at an elevation of 213 feet (65 m),[2] the same elevation as the huge and historically important Tulare Lake shore when it was full.[4] The community is located in the ZIP Code 93219 and in the area code 661.

History

On June 30, 1908, clergyman Colonel Allen Allensworth and Denison University graduate Professor William Alexander Payne[5][6] established the California Colony and Home Promoting Association.[6] Allensworth and Payne were the chief officers, with the other constituents being miner John W. Palmer; minister William H. Peck; and real estate agent Harry A. Mitchell (all of whom were Black men).[6] The Association purchased 20 acres of land from the Pacific Farming Company with the goal of establishing a town for Black soldiers. The land was situated at the then-extant Santa Fe rail line stop, titled "Solita."[3] The land was divided into individual parcels,[7][3] forming "a colony of orderly and industrious African Americans who could control their own destiny."[8]

Allensworth's reputation drew many from all over the country to the town, causing some to buy property sight-unseen in order to support the efforts. In the early 20th century, the area boasted a great boom and hosted California's first African American school district by 1910.[9]

The town was especially reported upon in 1912 to 1915, the period considered its apex as a thriving community.[8] Its growth was reported in The New York Age, the California Eagle (which emphasized that "there is not a single white person having anything to do with the affairs of the colony") and the Los Angeles Times, which labelled Allensworth as the "ideal Negro settlement."[8]

By 1914, the town had established a schoolhouse, thereby becoming California's first African American school district. It also had a courthouse, a Baptist church, a hotel, and a Tulare County library.[3]

However, multiple complications occurred in 1914. The Santa Fe rail system moved its railroad stop from Allensworth to Alpaugh.[3] In September 1914, Colonel Allensworth died in Monrovia, California, where he was struck by a motorcycle while crossing the street.[10] The town experienced extreme losses, coupled with severe drought due to water being redirected from the town causing decreased crop yields. Despite this, the 1915 voting registration showed "farmers, storekeepers, carpenters, nurses and more, all suggesting that the colony’s business and industrial output was prodigious."[8]

Many[quantify] residents left the area following World War I.[9]

The California Colony and Home Promoting Association's 1929 blueprint of Allensworth is available for viewership online via the California State Archives.[11]

The town of Allensworth was scheduled for demolition in 1966 when arsenic was found in the water supply.[9]

Legacy

The town was memorialized as a state park in 1974, and hosts seasonal events to preserve its history, which garner "thousands of visitors" from around the state. The area around the park is inhabited.[3] In 1976, the Colonel Allensworth Historic Park was established, a process which was started by Cornelius Ed Pope. Historic buildings from 1908 to 1918 have been restored in the town center.[12]

A number of the restored buildings are at the center of the 2022 documentary film Allensworth by James Benning. The film had its U.S. premiere at the 2022 Denver Film Festival[13] and its European premiere at the 2023 Berlinale.[14]

A children's historical novel Ellen of Allensworth by Janet Nichols Lynch was published in 2025, depicting life in Allensworth at the beginning of the Twentieth Century.[15]

Geography

Allensworth marks the eastern high-water shoreline of Tulare Lake, (once the largest U.S. lake outside the Great Lakes,) which supported one of the largest Indian populations on the continent, herds of elk, millions of water fowl, as well as a commercial fishery and ferry service.[16] Other townsites located on this historic shoreline include Lemoore on its northern tip, and Kettleman City on the western shore, while nearby Alpaugh is on the eastern end of a long, sandy ridge at elevation 210 ft. that was once called Hog Island. Due to diversions of the natural waterways since the mid to late 19th century, only a tiny remnant of Tulare Lake now remains. The last time Tulare Lake was full and overflowed its spillway (near Lemoore) was 1878.

Just north of Allensworth is the Pixley National Wildlife Refuge, 6,833-acre (27.65 km2) grassland and wetland habitats operated by the Department of the Interior, US Fish and Wildlife Service. Of great interest, thousands of sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis), use this refuge each winter from November through March. Red-tailed hawks (Buteo jamaicensis), are among the 141 type of birds that can be seen here.[17] Burrowing owls are sometimes present.[18] Also present are Pacific pond turtles, once an important part of Tulare Lake's fishery trade with San Francisco.

Adjacent to the town is Allensworth Ecological Reserve. The endangered San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica) can be found in this area.[17]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the CDP covers an area of 3.1 square miles (8.0 km2), all of it land.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 471 | — | |

| 2020 | 531 | 12.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[19] 1850–1870[20][21] 1880-1890[22] 1900[23] 1910[24] 1920[25] 1930[26] 1940[27] 1950[28] 1960[29] 1970[30] 1980[31] 1990[32] 2000[33] 2010[34] | |||

Allensworth first appeared as a census designated place in the 2010 U.S. census.[34]

The 2020 United States census reported that Allensworth had a population of 531. The population density was 171.2 inhabitants per square mile (66.1/km2). The racial makeup of Allensworth was 18.5% White, 3.8% African American, 1.1% Native American, 1.3% Asian, 0.2% Pacific Islander, 42.0% from other races, and 33.1% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 93.0% of the population.

The census reported that 100% of the population lived in households.

There were 128 households, out of which 65.6% included children under the age of 18, 50.8% were married-couple households, 17.2% were cohabiting couple households, 18.0% had a female householder with no partner present, and 14.1% had a male householder with no partner present. 7.8% of households were one person, and 6.2% were one person aged 65 or older. The average household size was 4.15. There were 111 families (86.7% of all households).

The age distribution was 38.4% under the age of 18, 9.6% aged 18 to 24, 25.4% aged 25 to 44, 19.4% aged 45 to 64, and 7.2% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27.8 years. For every 100 females, there were 89.6 males.

There were 138 housing units at an average density of 44.5 units per square mile (17.2 units/km2), of which 128 (92.8%) were occupied. Of these, 55.5% were owner-occupied, and 44.5% were occupied by renters.[35][36]

Education

The Allensworth School District, which covers the CDP,[37] hosts a single school serving grades K through 8.[38] That school is named Allensworth Elementary School.[39]

The high school district is the Delano Joint Union High School District.[37]

Government

In the California State Legislature, Allensworth is in the 16th senatorial district, represented by Democrat Melissa Hurtado, and in the 33rd Assembly district, represented by Republican Alexandra Macedo.[40]

In the United States House of Representatives, Allensworth is in California's 22nd congressional district, represented by Republican David Valadao.[41]

References

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 30, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Allensworth Census Designated Place". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b c d e f "Allensworth, California". Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ U.S. Geologic Survey: STRUCTURAL CONTROL OF INTERIOR DRAINAGE, SOUTHERN SAN JOAQUIN VALLEY, CALIFORNIA By George H. Davis and J. H. Green, Washington, D.C., and Sacramento, Calif. "The low point of Tulare Lake Bed is 178 feet above sea level; the divide to the north is 210 feet above sea level" ... "During periods of high runoff, Tulare Lake would fill to an elevation of 210 feet and would discharge north to the San Joaquin River and thence to the Pacific Ocean. Playas or salt flats did not form because through-flowing water periodically flushed out accumulated salt."

- ^ "'Promised Land': A Historically Black California Town Honors Its Proud, Painful Past — and Fights for Its Future". KQED. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c "William Payne Innovation Lab for Racial, Social, Political and Communal Sustainability". Denison University William Payne Innovation Lab. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ Gudde, Erwin; William Bright (2004). California Place Names (4th ed.). University of California Press. p. 9. ISBN 0-520-24217-3.

- ^ a b c d "Allensworth: California's First African-American Community". HistoryNet. June 12, 2006. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Park Brochure". Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Dixson, Brennon (February 20, 2023). "Allensworth, a one-time Black utopia, could rise again from the Central Valley dust". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Tract of California Colony and Home Promoting Association: Town of Allensworth - Public Utilities Commission Records, Administration Division Records, Formal Complaints (Cases), Case No. 2699: George P. Black vs. Allensworth Rural Water Company, California State Archives". Google Arts & Culture. Retrieved September 25, 2022.

- ^ Mikell, Robert (September 7, 2017). "The History of Allensworth, California (1908-)". Black Past. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved November 9, 2021.

- ^ "Allensworth". Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ "Allensworth". Retrieved February 21, 2023.

- ^ Lynch, Janet Nichols (2025). Ellen of Allensworth. Bedazzled Ink. ISBN 9781960373700.

- ^ Historic Tulare County: A Sesquicentennial History, 1852-2002, By Chris Brewer, page 28, and nearby.

- ^ a b Natural Resource Projects Inventory (NRPI) Catalog - Allensworth Ecological Reserve Restoration Project

- ^ Checklist of Birds of Pixley National Wildlife Refuge

- ^ "Decennial Census by Decade". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Almeda County to Sutter County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1870 Census of Population - Population of Civil Divisions less than Counties - California - Tehama County to Yuba County" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1890 Census of Population - Population of California by Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1900 Census of Population - Population of California by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1910 Census of Population - Supplement for California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 23, 2024. Retrieved August 12, 2024.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1930 Census of Population - Number and Distribution of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1940 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1960 Census of Population - General population Characteristics - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1970 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1980 Census of Population - Number of Inhabitants - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "2000 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b "2010 Census of Population - Population and Housing Unit Counts - California" (PDF). United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "Allensworth CDP, California; DP1: Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics - 2020 Census of Population and Housing". US Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2025.

- ^ "Allensworth CDP, California; P16: Household Type - 2020 Census of Population and Housing". US Census Bureau. Retrieved March 31, 2025.

- ^ a b Geography Division (December 18, 2020). 2020 Census - School District Reference Map: Tulare County, CA (PDF) (Map). Suitland, Maryland: U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved February 14, 2026. - Text list

- ^ "Allensworth School District". Tulare County Office of Education. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ "Allensworth Elementary - School Directory Details (CA Dept of Education)". www.cde.ca.gov. Retrieved November 16, 2021.

- ^ "Find Your Legislators". OpenStates. Plural. Retrieved May 9, 2023.

- ^ "California's 22nd Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved May 9, 2023.