D mt (Ge’ez: ደዐመተ, DʿMT theoretically vocalized as ዳዓማት, Daʿamat or ዳዕማት, Daʿəmat) was a kingdom located in Eritrea and northern Ethiopia that existed during the 10th and 5th centuries BC. Few inscriptions by or about this kingdom survive and very little archaeological work has taken place. As a result, it is not known whether Dʿmt ended as a civilization before the Kingdom of Aksum‘s early stages, evolved into the Aksumite state, or was one of the smaller states united in the Kingdom of Aksum possibly around the beginning of the 1st century.

Kingdom of dʿmt ደዐመተ | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8th c. BC–4th c. BC | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Capital | Yeha[1] | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Iron Age | ||||||||||

• Established | 8th c. BC | ||||||||||

• Disestablished | 4th c. BC | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

dʿmt (Ge'ez: ደዐመተ, romanized: dʿmt; theoretically vocalized ዳዓማት, *Daʿamat[2] or ዳዕማት, *Daʿəmat[3]) was a Ethio-Sabaean[4] kingdom located in present-day Eritrea and the northern Tigray Region of Ethiopia.

The exact dates of its existence remain unknown. However, a timeframe spanning from the end of the 8th century BC to the 6th century BC is a hypothesis.[5] Few inscriptions by or about this kingdom survive, and very little archaeological work has taken place. As a result, it is not known whether dʿmt ended as a civilization before the Kingdom of Aksum's early stages, evolved into the Aksumite state, or was one of the smaller states united in the Kingdom of Aksum, possibly around 150 BC.[6]

| History of Eritrea |

|---|

|

|

|

| History of Ethiopia |

|---|

|

History

Given the presence of a large temple complex, the capital of dʿmt may have been present-day Yeha, in Tigray Region, Ethiopia.[1] At Yeha, the temple to the god Ilmuqah is still standing.[7]

The kingdom developed irrigation schemes, used plows, grew millet, and made iron tools and weapons.[citation needed]

Some modern historians including Stuart Munro-Hay, Rodolfo Fattovich, Ayele Bekerie, Cain Felder, and Ephraim Isaac consider this civilization to be indigenous, although Sabaean-influenced due to the latter's dominance of the Red Sea, while others like Joseph Michels, Henri de Contenson, Tekle-Tsadik Mekouria, and Stanley Burstein have viewed dʿmt as the result of a mixture of Sabaeans and indigenous peoples.[8][9] Some sources consider the Sabaean influence to be minor, limited to a few localities, and disappeared after a few decades or a century, perhaps representing a trading or military colony in some sort of symbiosis or military alliance with the civilization of dʿmt or some other proto-Aksumite state.[10][11]

Archaeologist Rodolfo Fattovich believed that there was a division in the population of dʿmt and northern Ethiopia due to the kings ruling over the 'sb (Sabaeans) and the 'br, the 'Reds' and the 'Blacks'.[12] Fattovich also noted that the known kings of dʿmt worshipped both South Arabian and indigenous gods named 'str, Hbs, Dt Hmn, Rb, Šmn, Ṣdqn and Šyhn.[12]

After the fall of dʿmt, the plateau came to be dominated by smaller unknown successor kingdoms. This lasted until the rise of one of these polities during the first century BC, the Aksumite Kingdom.[13]

Known rulers

The following is a list of four known rulers of dʿmt, in chronological order:[9]

| Term | Name | Consort name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dates from ca. 700 BC to ca. 650 BC | |||

| Mlkn Wʿrn Ḥywt | ʿArky(t)n | contemporary of the Sabaean mukarrib Karib'il Watar | |

| Mkrb, Mlkn Rdʿm | Smʿt | ||

| Mkrb, Mlkn Ṣrʿn Rbḥ | Yrʿt | Son of Wʿrn Ḥywt, "King Ṣrʿn of the tribe YGʿḎ [=Agʿazi, cognate to Ge'ez], mkrb of DʿMT and SB'" | |

| Mkrb, Mlkn Ṣrʿn Lmn | ʿAdt | Son of Rbḥ, contemporary of the Sabaean mukarrib Sumuhu'alay, "King Ṣrʿn of the tribe YGʿḎ, mkrb of DʿMT and SB'" |

See also

References

- ^ a b Shaw, Thurstan (1995), The Archaeology of Africa: Food, Metals and Towns, Routledge, p. 612, ISBN 978-0-415-11585-8

- ^ L'Arabie préislamique et son environnement historique et culturel: actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 24–27 Juin 1987; page 264

- ^ Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: A–C; page 174

- ^ Avanzini 2016, p. 127.

- ^ Avanzini 2016, p. 128.

- ^ Uhlig, Siegbert (ed.), Encyclopaedia Aethiopica: D-Ha. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz Verlag, 2005. p. 185.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay (2002). Ethiopia: The Unknown Land. I.B. Taurus. p. 18.

- ^ Stuart Munro-Hay, Aksum: An African Civilization of Late Antiquity. Edinburgh: University Press, 1991, p. 57.

- ^ a b Nadia Durrani, The Tihamah Coastal Plain of South-West Arabia in its Regional context c. 6000 BC – AD 600 (Society for Arabian Studies Monographs No. 4) . Oxford: Archaeopress, 2005, p. 121.

- ^ Munro-Hay, Aksum, p. 57.

- ^ Phillipson (2009). "The First Millennium BC in the Highlands of Northern Ethiopia and South–Central Eritrea: A Reassessment of Cultural and Political Development". African Archaeological Review. 26 (4): 257–274. doi:10.1007/s10437-009-9064-2. S2CID 154117777.

- ^ a b Fattovich, Rodolfo (1990). "Remarks on the Pre-Aksumite Period in Northern Ethiopia". Journal of Ethiopian Studies. 23: 17. ISSN 0304-2243. JSTOR 44324719.

- ^ Pankhurst, Richard K.P. Addis Tribune, "Let's Look Across the Red Sea I", January 17, 2003 (archive.org mirror copy)

Sources

- Avanzini, Alessandra (2016). By land and by sea: a history of South Arabia before Islam recounted from inscriptions. L'Erma Di Bretschneider.

Further reading

- Prioletta, Alessia; Robin, Christian Julien; Schiettecatte, Jérémie; Gajda, Iwona; Nuʿmān, Khaldūn Hazzāʿ (2021). "Sabaeans on the Somali coast". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 32 (S1): 328. doi:10.1111/aae.12202.

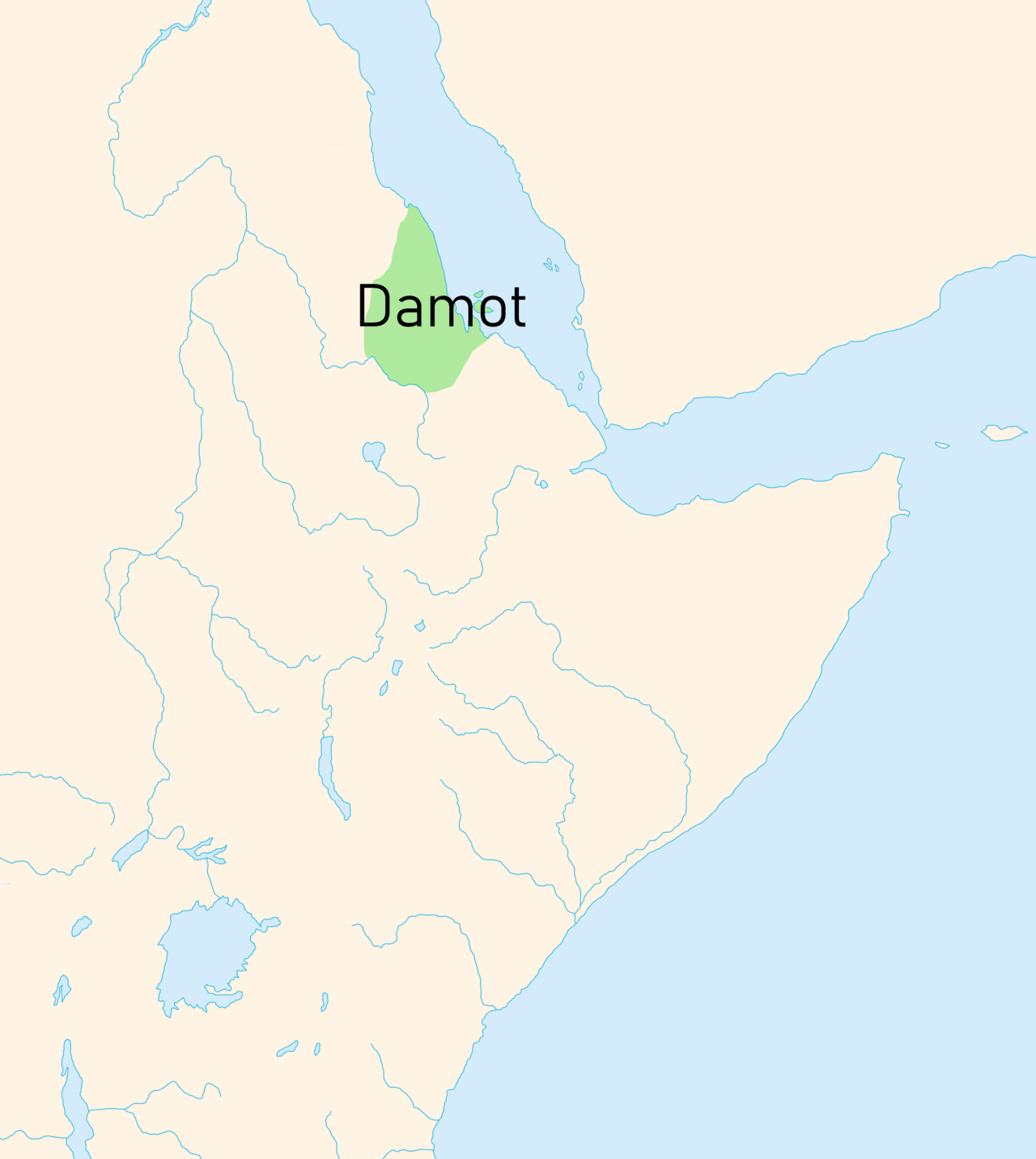

Kingdom of Damot

Kingdom of Damot | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| c. 10th/13th century–c. 16th century | |||||||||

The kingdom of Damot and its neighbours circa 1200 AD | |||||||||

| Capital | Maldarede 9°23′N 37°34′E / 9.39°N 37.56°E | ||||||||

| Common languages | Gonga, and other North Omotic languages | ||||||||

| Religion | Paganism, Christianity | ||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||

| Motalami | |||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Established | c. 10th/13th century | ||||||||

• Conquered by Ethiopia | c. 1316 | ||||||||

• Dissolution (By the 16th century, Damot was further fragmented and ultimately overrun during the Oromo expansion) | c. 16th century | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | Ethiopia | ||||||||

| History of Ethiopia |

|---|

|

The Kingdom of Damot was a medieval kingdom in what is now western Ethiopia.[1] The territory was positioned below the Blue Nile.[2] Possibly formed in the 10th century, it was a powerful state by the 13th century that forced the Sultanate of Shewa to pay tributes.[3][4] It also annihilated the armies of the Zagwe dynasty that were sent to subdue its territory. Damot conquered several Muslim and Christian territories.[5] The Muslim state Showa and the new Christian state under Yekuno Amlak formed an alliance to counter the influence of Damot in the region.[6]

Some academics have proposed that Damot was equivalent to the Kingdom of Wolaita, with the most famous ruler of Damot, Motolomi Sato, coming from the Wolaita Malla dynasty which ruled from the 13th to 16th centuries, before being replaced by the Tigre Malla dynasty amid the Oromo expansion.[7]: 59 Part of the kingdom's former northern territory continued to be under Ethiopian rule as the province of the same name around Gojjam.

History

Possibly formed in the 10th century, Damot was a powerful state by the 13th century that forced the Sultanate of Showa to pay tribute.[4] The kings of Damot, who bore the title motalami, resided in a town which, according to the hagiography of Tekle Haymanot, was called Maldarede.[8] The hagiography also states the kingdom was likely bordered on the north by Bete Amhara according to E. A. Wallis Budge. Zena Petros failed a campaign he led against Damot to extract tribute. 14th-century Arab historian Ibn Khaldun mentions the ancestors of Walasma (Ifat Sultanate) were once tributary to the kingdom.[9]

Damot was conquered by Emperor Amda Seyon in 1316/7. His royal chronicle recounted that "all the people of Damot [came] into my hands; its king, its princes, its rulers, and its people, men and women without number, whom I exiled into another area."[10]: 65 Amda Seyon seemingly left the Damotian royal family in power, for the title motälämi continued to be used until the 15th century.[10]: 71 Al-Mufaddal ibn Abi al-Fada'il in the 14th century writes that Damot alongside Harla Kingdom were forced to pay tribute to Abyssinia.[11]

Damot was originally located south of the Abay River and west of the Muger River.[12] However, the kingdom’s decline began in the 14th century, as suggested by some sources, such as Paulos Milkias, who argues that the Oromo conquest of Damot may have started earlier than widely believed.[12] This earlier timeline helps explain why Aba Bahrey, writing in the 16th century, provides little detail about Damot’s fall—it had already been displaced or weakened long before his time.[13] Instead, Aba Bahrey focuses on how the Oromos used the "west," once part of Damot’s territories, as a base for military campaigns, crossing the Abay River to invade the Kingdom of Ennarea in the "southwest" (modern-day Jimma).[14] In the medieval period gold and slaves were acquired by Muslim traders to the Kingdom of Damot and the Hadiya Sultanate, who were known for slave raiding, to the Christian Amhara who (during that time) opposed castration. [15]

By the late 16th century, under the leadership of Mula'ata Lubas (1586–1594), the Macha Oromo overran Ennarea amid the Oromo expansion and forced its clans to flee across the Abay River into Gojjam. Many of these displaced populations settled in the sub-provinces of Bure Damot and Daga Damot, though the Oromos pursued them until they were fully subdued.[12] Unlike other conquering groups, the Oromos incorporated the people they defeated, requiring them to adopt Oromo culture and language. This practice boosted their numbers and facilitated their expansion into the highlands.[12]

Paulos Milkias suggested that areas like Walal (near Mount Tullu Walal in Qelem, Wallaga) were inhabited by Kafa-descended people known as Busase or Bushasho before the Oromo conquest. Following the fall of Damot, a Christian temple in the region was converted into a church, and descendants of the Busase people continue to inhabit parts of Anfilo, producing coffee for both local and export consumption.[12]

Their territory extended east beyond the Muger as far as the Jamma.[16] The province of Damot remained part of the Ethiopian Empire well after the Zemene Mesafint began, unlike other southern regions. The ruler of Damot was typically from Gojjam and held the title Ras.

Religion

The population of Damot adhered to its own religion dominated by a deity called Däsk. This continued on even well after being conquered by the Christian Ethiopian Empire, which repeatedly led to conflict between the locals and the Christian garrison troops.[10]: 80 Parts of the population seemingly remained pagan until the late 16th century.[17]

It is claimed in the Hagiography of Tekle Haymanot that the latter managed to convert the ruler of Damot to Christianity.[18]

References

- ^ Shinn, David (2013). Historical Dictionary of Ethiopia. Scarecrow Press. p. 111. ISBN 9780810874572.

- ^ Shillington, Kevin (4 July 2013). Encyclopedia of African History 3-Volume Set. Routledge. ISBN 9781135456696.

- ^ Hassan, Mohammed. Oromo of Ethiopia 1500 (PDF). University of London. p. 4.

- ^ a b González-Ruibal, Alfredo (2024-03-01). "Landscapes of Memory and Power: The Archaeology of a Forgotten Kingdom in Ethiopia". African Archaeological Review. 41 (1): 71–95. doi:10.1007/s10437-024-09575-8. hdl:10261/361960. ISSN 1572-9842.

- ^ Bounga, Ayda (2014). "The kingdom of Damot: An Inquiry into Political and Economic Power in the Horn of Africa (13th c.)". Annales d'Ethiopie. 29: 262. doi:10.3406/ethio.2014.1572.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed. Oromo of Ethiopia (PDF). University of London. p. 4.

- ^ Aalen, Lovise (2011-06-24). The Politics of Ethnicity in Ethiopia: Actors, Power and Mobilisation under Ethnic Federalism. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-20937-4.

- ^ Bouanga 2014, pp. 33–37.

- ^ Ibn Haldun. Encyclopedia Aethiopica.

- ^ a b c Ayenachew, Deresse (2020). "Territorial Expansion and Administrative Evolution under the "Solomonic" Dynasty". In Samantha Kelly (ed.). A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Brill.

- ^ Harla. Encyclopedia Aethiopica.

- ^ a b c d e Milkias, Paulos (2011). Ethiopia. Internet Archive. Santa Barbara, Calif. : ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-59884-257-9.

- ^ Hassen, Mohammed (2015). The Oromo and the Christian Kingdom of Ethiopia: 1300-1700. Boydell & Brewer. ISBN 978-1-84701-117-6.

- ^ Mohammed Hassen (1990). The Oromo of Ethiopia: A History 1570-1860.

- ^ The Golden Rhinoceros: Histories of Africa's Middle Ages" - Francois-Xavier Fauvelle, 2018 https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Golden_Rhinoceros.html?id=gej5DwAAQBAJ&source=kp_book_description

- ^ G.W.B. Huntingford, Historical Geography of Ethiopia from the first century AD to 1704 (London: British Academy, 1989), p. 69

- ^ Fauvelle, François-Xavier (2020). "Of Conversion and Conversation: Followers of Local Religions in Medieval Ethiopia". In Samantha Kelly (ed.). A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Brill. p. 140.

- ^ Lusini, Gianfrancesco (2020). "The Ancient and Medieval History of Eritrean and Ethiopian Monasticism: An Outline". In Samantha Kelly (ed.). A Companion to Medieval Ethiopia and Eritrea. Brill. p. 207.

Further reading

- Bouanga, Ayda (2013). Le Damot dans l'histoire de l'Ethiopie (XIIIe-XXe siècles) : recompositions religieuses, politiques et historiographiques (in French). Université Panthéon-Sorbonn.

- Bouanga, Ayda (2014). "Le royaume du Damot : enquête sur une puissance politique et économique de la Corne de l'Afrique (XIIIe siècle)" (PDF). Annales d'Ethiopie (in French). 29: 27–58. doi:10.3406/ethio.2014.1557.