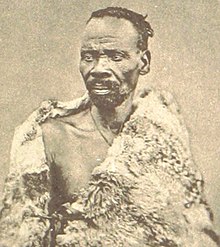

Sekhukhune, King of the MarotengEdit

Sekhukhune, became king of the Maroteng also known as the Bapedi after the death of his father Sekwati I in 1861 and usurping the intended heir of the Bapedi nation, Mampuru II.

He fought wars against the Boer of the South African Republic (Dutch: Zuid-Afrikaansche Republiek) British empire and the Swazi. After his defeat at the hands the British and 10,000 Swazi warriors, he was arrested in 1881 in the ZAR capital in Pretoria.

He was assassinated by his half-brother Mampuru II, in 1882. Mampuru was later hanged in Pretoria by the ZAR the following year.

The London Times, which was not known to write about African ruling affairs, wrote a tribute to the slain warrior King on August 29, 1882.

Shango of the Oyo EmpireEdit

Shango was the third king of the Oyo in Yorubaland who brought prosperity to the kingdom he inherited. Many stories have been told about him, and several myths surround him. He stands as the cornerstone of many Afro-Caribbean religions.[1]

In the Yoruba religion, Shango (Xangô or Changó in Latin America), is perhaps the most popular Orisha. He is the orisha of thunder and one of the principal ancestors of the Yoruba people. In the Santeria religion of the Caribbean, Shango is considered to be the focal point as he represents the Oyos of West Africa. The Oyo empire sold a lot of people to the Atlantic slave trade who then took them to the Caribbean and South America. It is primarily for this reason that every major Orisha initiation ceremony performed in the New World within the past few hundred years has been based on the traditional Shango ceremony of Ancient Oyo. Such ceremonies survived the Middle Passage and are considered to be the most complete traditional practices to have arrived on American shores.

Shango’s sacred colors are ‘red and white; his sacred number is 6; his symbol is the oshe, which represents swift and balanced justice. He is owner of the bata (3 double-headed drums) and of music in general, as well as the art of dance.[2]

Shango is venerated in Santería, Candomblé Ketu, Umbanda, and Vodou.[3]

In art, Shango is depicted with a double-axe on his three heads. He is associated with the holy animal, the ram.

Shaka ZuluEdit

Shaka (sometimes spelled Tshaka, Tchaka or Chaka; c. 1787 – c. 22 September 1828) was a Zulu leader.[4][5]

He is widely credited with transforming the Zulu from a small tribe into the beginnings of a nation-state that held sway over the large portion of Southern Africa that stretches between the Phongolo and Mzimkhulu rivers. His military prowess and destructiveness have been widely studied by modern scholarship. One Encyclopædia Britannica article (Macropaedia Article “Shaka” 1974 ed) asserts that he was something of a military genius for his reforms and innovations. Other writers take a more limited view of his achievements. Nevertheless, his statesmanship and vigour in assimilating some neighbours and ruling by proxy marks him as one of the greatest of the Zulu chieftains.

The Ajuran EmpireEdit

The Ajuran Sultanate (Somali: Dawladdii Ajuuraan, Arabic: الدولة الأجورانيون), also spelled Ajuuraan Sultanate, and often simply as Ajuran, was a Somali empire of the medieval and early modern periods that dominated the Indian Ocean trade. It was a Somali Muslim sultanate that ruled over large parts of the Horn of Africa from the early 1200s to the late 1600s. Through a strong centralized administration and an aggressive military stance toward invaders, the Ajuran Sultanate successfully resisted an Oromo invasion from the west and a Portuguese incursion from the east during the “Gaal Madow” war and Ajuran-Portuguese war. Trading routes dating from the ancient and early medieval periods of Somali maritime enterprise were strengthened or re-established, and foreign trade and commerce in the coastal provinces flourished

King Jaja of OpoboEdit

King Jaja of Opobo (1821–1891) was an Ijaw monarch. He was one of the most prominent rulers to come from the Niger Delta.[6]

Early life, Jubo JuboghaEdit

Born in Igboland and sold as a slave to a Bonny trader at the age of twelve, he was named Jubo Jubogha by his first master. He was later sold to Chief Alali, the powerful head of the Opobu Manila Group of Houses. Called Jaja by the British, this gifted and enterprising individual eventually became one of the most powerful men in the eastern Niger Delta.

The Niger DeltaEdit

The Niger Delta, where the Niger empties itself into the Gulf of Guinea in a system of intricate waterways, was the site of unique settlements called city-states.

From the 15th to the 18th centuries, Bonny, like the other city-states, gained its wealth from the profits of the slave trade. Here, an individual could attain prestige and power through success in business and, as in the case of Jaja, a slave could work his way up to head of state. The House was a socio-political institution and was the basic unit of the city-state.

In the 19th century—after the abolition of the slave trade in 1807—the trade in slaves was supplanted by the trade in palm oil, which was so vibrant that the region was named the Oil Rivers area.

The Houses in Bonny and other city-states controlled both the internal and external palm oil trade because the producers in the hinterland were forbidden to trade directly with the Europeans on the coast; the Europeans never left the coast for fear of malaria.

The rise of King JajaEdit

Astute in business and politics, Jaja became the head of the Anna Pepple House, extending its activities and influence by absorbing other houses, increasing operations in the hinterland and augmenting the number of European contacts. A power struggle ensued among rival factions in the houses at Bonny, leading to the breakaway of the faction led by Jaja. He established a new settlement, which he named Opobo. He became King Jaja of Opobo and declared himself independent of Bonny.

Strategically located between Bonny and the production areas of the hinterland, King Jaja controlled trade and politics in the delta. In so doing he curtailed trade at Bonny, and at the end of his ascendancy, fourteen of the eighteen Bonny houses had moved to Opobo.

In a few years, he had become so wealthy that he was shipping palm oil directly to Liverpool himself. The British consul could not tolerate this situation. Jaja was offered a treaty of “protection”, in return for which the chiefs usually surrendered their sovereignty. After Jaja’s initial opposition, he was reassured, in rather vague terms, that neither his authority nor the sovereignty of Opobo would be threatened.

The fall of Jaja and scramble for AfricaEdit

Jaja continued to regulate trade and levy duties on British traders, to the point where he ordered a cessation of trade on the river until one British firm agreed to pay duties. Jaja refused to comply with the consul’s order to terminate these activities, despite threats made by the consul that he would bombard Opobo. Unknown to Jaja, the Scramble for Africa had taken place and Opobo was part of the territories allocated to Great Britain. Lured into a meeting with the British consul aboard a warship, Jaja was arrested and sent to Accra, where he was summarily tried and found guilty of “treaty breaking” and “blocking the highways of trade”.[7]

He was deported to St. Vincent (Saint Vincent and the Grenadines), West Indies, and four years later, he died en route to Nigeria after he was permitted to return. In addition, the discovery of quinine as the cure for malaria enabled the British traders to bypass the middlemen and deal directly with the palm oil producers, thus precipitating the decline of the importance of the city-states.[7]

Askia Mohammed I (Askia the Great) of TimbuktuEdit

Mohammed Ben Abu Bekr “Askia the Great” (1538),[8][9] the favored general of Sunni Ali, believed that he was entitled to the throne after Sunni Ali’s death, rather than Ali’s son, Abu Kebr.

Claiming that the power was his by right of achievement, Mohammed attacked the new ruler a year after his acsession and defeated him in one of the bloodiest battles in history. When one of Sunni Ali’s daughters heard the news, she cried out “Askia”, which means “forceful one.” This title was taken by Mohammed as his regnal name.

Askia began by consolidating his vast empire and establishing harmony among the conflicting religions and political elements. Under the leadership of Askia, the Songhay Empire flourished until it became one of the richest empires of that period, from any region. Timbuctoo became known as “The Center of Learning”, “The Mecca of the Sudan”, and “The Queen of the Sudan”.

With his empire firmly established, Askia resumed his attack on the unbelievers, carrying the rule of Islam into new lands. Askia the Great made Timbuktu (Archaic English: Timbuctoo; Koyra Chiini: Tumbutu; French: Tombouctou) one of the most famous centers of commerce and learning on Earth. The brilliance of the city was such that it still shines in the imagination after three centuries like a star which, though dead, continues to send its light toward us.

Such was its splendor that in spite of its many vicissitudes after the death of Askia, the vitality of Timbuktu is not extinguished.

Oyo EmpireEdit

The EmpireEdit

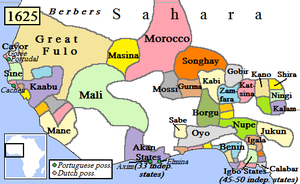

The Oyo Empire (c. 1400–1835) was a West African empire of present-day Nigeria. The empire grew from a kingdom established by the Yoruba at the turn of the 14th century and grew to become one of the largest West African states encountered by colonial explorers. It rose to pre-eminence through wealth gained from trade and its possession of a powerful cavalry known as the Eso Ikoyi. The Oyo Empire was the most politically important state in the region from the mid-17th to the late 18th century, holding sway not only over other Yoruba kingdoms in modern-day Nigeria, Benin, and Togo, but also over other African kingdoms, most notable being the Fon Dahomey (in present-day Benin).

Mythical originsEdit

The mythical origins of the Oyo Empire lie with Oranyan (also known as Oranmiyan), the youngest prince of the Yoruba Kingdom of Ile-Ife. Oranyan made an agreement with his brother to launch a punitive raid on their northern neighbors for insulting their father, the Oba Oduduwa, first of the Oonis of Ife. On the way to the battle, the brothers quarrelled and the army split up.[10] Oranyan’s force was too small to make a successful attack, so he wandered the southern shore until reaching Bussa. There the local chief entertained him and provided a large snake with a magic charm attached to its throat. The chief instructed Oranyan to follow the snake until it stopped somewhere for seven days and disappeared into the ground. Oranyan followed the advice and founded Oyo where the serpent stopped. The site is remembered as Ajaka. Oranyan made Oyo his new kingdom and became the first “oba” (meaning ‘king’ or ‘ruler’ in the Yoruba language) with the title of “Alaafin of Oyo” (Alaafin means ‘owner of the palace’ in Yoruba).[11]

Early periodEdit

Oranyan, the first oba of Oyo, was succeeded by Oba Ajaka, Alaafin of Oyo. Ajaka was deposed because he was seen to be lacking Yoruba military virtues and allowing his sub-chiefs too much independence. Leadership was then conferred upon Ajaka’s brother, Jakuta, who was later deified as the deity Shango. Ajaka was restored after Shango’s death. Ajaka returned to the throne thoroughly more warlike and oppressive. His successor, Kori, managed to conquer the rest of what later historians would refer to as metropolitan Oyo.[11]

Oyo-IleEdit

The heart of metropolitan Oyo was its capital at Oyo-Ile, (also known as Katunga, Old Oyo, or Oyo-oro).[12] The two most important structures in Oyo-Ile were the ‘afin’, or palace of the Oba, and his market. The palace was at the center of the city, close to the Oba’s market which was called ‘Oja-oba’. Around the capital was a tall earthen wall for defense with 17 gates. The importance of the two large structures (the palace and the Oja Oba) signified the importance of the king in Oyo.

Ghana EmpireEdit

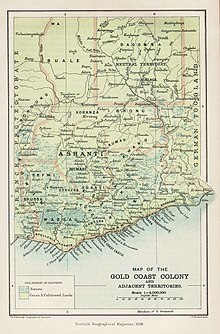

Ashanti Kingdom[13]Edit

The Ashanti, or Asante, are a major ethnic group in modern Ghana. The Ashanti speak Twi, an Akan language similar to Fante. For the Ashanti (Asante) Confederacy, see Asanteman.

Prior to European colonization, the Ashanti people developed a large and influential empire in West Africa. The Ashanti later created the powerful Ashanti Confederacy and became the dominant presence in the region.

The Ashanti, Adansi, Akyem, Assin, and Denkyira peoples of Ghana, like the Baoulé of Côte d’Ivoire, are subgroups of the West African Akan nation which is said to have migrated from the vicinity of the north-western Niger River after the fall of the Ghana Empire in the 13th century.[14] Evidence of this is seen in royal courts of the Akan kings reflected by that of the Ashanti kings whose processions and ceremonies show remnants of ancient Ghana ceremonies. Ethnolinguists have substantiated the migration by tracing word usage and speech patterns along West Africa.[15]

Thus, although the Ghana Empire was geographically different from present-day Ghana, some of its people, specifically the Akan, moved to what is today Ghana, hence the historicity of the name. In fact, the North African Almoravid dynasty gold coin was renowned throughout the medieval world as being made of the purest of golds, since West African gold was 92 percent pure at the time it was mined, higher than old Egyptian gold ore, which started at 85 percent, a figure which was later refined to 95 percent. Evidence of early Ashanti connections to the Islamic world is the Ashanti word for money – “sikka” – the same as the Arabic word for minting money.[16]

Bambara EmpireEdit

The Bamana Empire (also Bambara Empire or Ségou Empire) was a large pre-colonial West African state based at Ségou, now in Mali. It was ruled by the Kulubali or Coulibaly dynasty established circa 1640 by Fa Sine also known as Biton-si-u. The empire existed as a centralized state from 1712 to the 1861 invasion of Toucouleur conqueror El Hadj Umar Tall.

The Bambara Empire was structured around traditional Bambara institutions, including the kòmò, a body to resolve theological concerns. The kòmò often consulted religious sculptures prior to making their decisions, particularly the four state boliw, large altars designed to aid the acquisition of political power.

In the Battle of Noukouma, in 1818, Bambara forces met and were defeated by Fula Muslim fighters rallied by the jihad of Cheikou Amadu (or Seku Amadu) of Massina. The Bambara Empire survived but was irreversibly weakened. Seku Amadu’s forces decisively defeated the Bambara, taking Djenné and much of the territory around Mopti, and forming it into a Massina Empire. Timbuktu would fall as well in 1845.

The real end of the empire, however, came at the hands of El Hadj Umar Tall, a Toucouleur conqueror who swept across West Africa from Dinguiraye. Umar Tall’s mujahideen readily defeated the Bambara, seizing Ségou itself on March 10, 1861, forcing the population to convert to Islam, and declaring an end to the Bambara Empire (which effectively became part of the newly declared Toucouleur Empire).

Mali EmpireEdit

The Mali Empire or Manding Empire or Manden Kurufa was a medieval West African state of the Mandinka from 1235 to 1645. The empire was founded by Sundiata Keita and became renowned for the wealth of its rulers, especially Mansa Musa I. The Mali Empire had many profound cultural influences on West Africa, allowing the spread of its language, laws and customs along the Niger River.

The Mali Empire grew out of an area referred to by its contemporary inhabitants as Manden.[17]

Manden, named for its inhabitants the Mandinka (initially Manden’ka with “ka” meaning people of),[18] comprised most of present-day northern Guinea and southern Mali. The empire was originally established as a federation of Mandinka tribes called the Manden Kurufa (literally Manden Federation), but it later became an empire ruling millions of people from nearly every ethnic group imaginable in West Africa.

The naming origins of the Mali Empire are complex and still debated in scholarly circles around the world. While the meaning of “Mali” is still contested, the process of how it entered the regional lexicon is not. As mentioned earlier, the Mandinka of the Middle Ages referred to their ethnic homeland as “Manden”.

Among the many different ethnic groups surrounding Manden were Pulaar speaking groups in Macina, Tekrur and Fouta Djallon. In Pulaar, the Mandinka of Manden became the Malinke of Mali.[19]

So while the Mandinka people generally referred to their land and capital province as Manden, its semi-nomadic Fula subjects residing on the heartland’s western (Tekrur), southern (Fouta Djallon) and eastern borders (Macina) popularized the name Mali for this kingdom and later empire of the Middle Ages.

The Mandinka kingdoms of Mali or Manden had already existed several centuries before Sundiata’s unification as a small state just to the south of the Soninké empire of Wagadou, better known as the Ghana Empire.[20]

This area was composed of mountains, savannah and forests, providing ideal protection and resources for the population of hunters.[21] Those not living in the mountains formed small city-states such as Toron, Ka-Ba and Niani.

The Keita dynasty from which nearly every Mali emperor came traces its lineage back to Bilal,[22] the faithful muezzin of Islam’s prophet Muhammad. It was common practice during the Middle Ages for both Christian and Muslim rulers to tie their bloodline back to a pivotal figure in their faith’s history. So while the lineage of the Keita dynasty may be dubious at best, oral chroniclers have preserved a list of each Keita ruler from Lawalo (supposedly one of Bilal’s seven sons whom settled in Mali) to Maghan Kon Fatta (father of Sundiata Keita).

Songhay EmpireEdit

Dahomey KingdomEdit

Ile Ife KingdomEdit

Now part of present-day Nigeria,[23][24][25] Ile-Ife, also known as Ife, is the holy city of the Yoruba people, a large proportion of which live in Nigeria in West Africa. Ile-Ife appears in myths as the birthplace of life and the location where the first humans sprang forth.

The myth – Where the world beganEdit

According to Yoruba mythology, the world was originally a marshy, watery wasteland. In the sky above lived many gods, including the supreme god called Olorun Olodumare. These gods sometimes descended from the sky on spiderwebs and played in the marshy waters, but there was no land or human being there.

One day Olorun called orisha-nla (the great god) Obatala, and told him to create solid land in the marshy waters below. He gave the Orisha a pigeon, a hen, and the shell of a snail containing some loose earth. Obatala descended to the waters and threw the loose earth into a small space. He then set loose the pigeon and hen, which began to scratch the earth and move it around. Soon the birds had covered a large area of the marshy waters and created solid ground.

The Orisha reported back to Olorun, who sent a chameleon to see what had been accomplished. The chameleon found that the earth was wide but not very dry. After a while, Olorun sent the creature to inspect the work again. This time the chameleon discovered a wide, dry land, which was called Ife (meaning “wide”) and Ile (meaning “house”). All other earthly dwellings later evolved from colonies of Ile-Ife, and it was revered forever after as a sacred spot. It remains the home of the Oni, the spiritual leader of the Yoruba.

Ancient historyEdit

The peoples who lived in Yorubaland, at least by the 4th century BCE, were not initially known as the Yoruba, although they shared a common language group. Both archaeology and traditional Yoruba oral historians confirm the existence of people in this region for several millennia. Yoruba spiritual heritage maintains that the Yoruba clans are a unique people who were originally created at Ile-Ife.

Legend holds that the creation was delegated by the supreme spiritual force, Olodumare, as stated above. This task, which was first attributed to orisha-nla Obatala may have actually been conducted by the Orishas Oduduwa and Eshu, who himself served as the divine messenger.

The name “Yoruba” is most likely an adaptation of ‘Yo ru ebo’, meaning “will venerate (make offerings to the) Orisha”. This refers to the Aborisha spiritual religion of the Yoruba, which existed for centuries prior to Islamic and Christian proselytism. The Yoruba civilization remains one of the most technologically and artistically advanced in West Africa to this time.

OduduwaEdit

Some early contemporary historians contend that the Yoruba are not indigenous to Yorubaland, but are descendants of immigrants to the region. This version of history contends that Oduduwa was, in fact, a mortal king, from Arabia or Egypt, under whose leadership the Oyo region of Yorubaland was conquered sometime in the 11th century and the kingdom of Ife as it is currently constituted was established. Oduduwa’s relatives established kingdoms in the rest of Yorubaland. More traditional sources however give a local origin to Oduduwa

One of Oduduwa’s sons, Oranmiyan, took the throne of Benin and expanded the Oduduwa Dynasty eastwards. Further expansion led to the establishment of the Yoruba in what are now Southwest Nigeria, Benin, and Togo, with Yoruba city-states acknowledging the spiritual primacy of the ancient city of Ile Ife. The southeastern Benin Empire, ruled by a dynasty that traced its ancestry to Ifẹ and Oduduwa but largely populated by the Edo and other related ethnicities, also held considerable sway in the election of nobles and kings in eastern Yorubaland.

The Benin Kingdom, Benin CityEdit

Founded around the 10th century, Benin served as the capital of the Kingdom of Benin, the empire of the Oba of Benin, which flourished from the 14th through the 17th century. The Walls of Benin have been undergoing preservation and restoration procedures for years. After Benin was visited by the Portuguese in 1472, historical Benin grew rich during the 16th and 17th centuries through the export of some tropical products.[26][27]

Benin Kingdom of Nigeria vs. Benin RepublicEdit

The Bight of Benin (Republic of Benin)‘s shore was part of the so-called “Slave Coast“, from where many West Africans were sold (usually by local rulers) to foreign slave traders. In the early 16th century the Oba sent an ambassador to Lisbon, and the King of Portugal sent Christian missionaries to Benin. Some residents of Benin could still speak a pidgin Portuguese in the late 19th century. To preserve Benin’s (of Nigeria) independence, bit by bit the Oba banned the export of goods from Benin, until the trade was exclusively in palm oil.

On 1 February 1852, the whole Bight of Benin (Republic of Benin) became a British protectorate where a Consul (representative) represented the protector, until on the 6th of August, 1861, the Bights of Biafra and Benin became a united British protectorate, again under a British Consul.[27]

In a punitive expedition conducted in 1897, a 1200-strong force, under the command of Admiral Sir Harry Rawson, conquered and sacked the city. Due to this the “Benin Bronzes“: portrait figures, busts, and groups created in iron, carved ivory, and especially in brass (conventionally called “bronze”), are on display in museums around the world. A scattered catalogue of some 2,500 pieces, the collection arguably constitutes the most argued over pool of antiquities after the disputed treasures of Ancient Egypt itself. After the fall of Benin, the British set apart Warri province in a bid to curb the Oba’s imperial power. The Benin monarchy was restored in 1914, but true power now lay with the colonial administration of Nigeria.[27]

Queen Amina of Zaria[28]Edit

The seven original states of Hausalar d: Katsina, Daura, Kano, Zazzau, Gobir, Rano, and Garun Gabas cover an area of approximately 1,300 square kilometres (500 sq mi) and comprise the heart of the Hausa realm. In the 16th century, Queen Bakwa Turunku built the capital of Zazzau at Zaria, named after her younger daughter. Eventually, the entire state of Zazzau was renamed Zaria, which is now a province and traditional kingdom in present-day Nigeria.

However, it was her elder daughter, the legendary Amina (or Aminatu), who inherited her mother’s warlike nature. Amina was 16 years old when her mother became queen and she was given the traditional title of Magajiya, an honorific borne by the daughters of monarchs. She honed her military skills and became famous for her bravery and military exploits, as she is celebrated in song as “Amina, daughter of Nikatau, a woman as capable as a man.”

Amina is credited as the architectural overseer who created the strong earthen walls that surround her city, which were the prototype for the fortifications used in all Hausa states. She subsequently built many of these fortifications, which became known as ganuwar Amina or Amina’s walls, around various conquered cities.

The objectives of her conquests were twofold: extension of her nation beyond its primary borders and reducing the conquered cities to a vassal status. Sultan Muhammad Bello of Sokoto stated that, “She made war upon these countries and overcame them entirely so that the people of Katsina paid tribute to her and the men of Kano and… also made war on cities of Bauchi till her kingdom reached to the sea in the south and the west.” Likewise, she led her armies as far as Nupe and, according to the Kano Chronicle, “The Sarkin Nupe sent her (i.e. the princess) 40 eunuchs and 10,000 kola nuts. She was the first in Hausaland to own eunuchs and kola nuts.”[citation needed]

Amina was a pre-eminent gimbiya (princess) but various theories exist as to the time of her reign or if she ever was a queen. One explanation states that she reigned from approximately 1536 to 1573, while another posits that she became queen after her brother Karama’s death, in 1576. Yet another claims that although she was a leading princess and de facto ruler, she was never a titular queen.

Despite the discrepancies in the tale of her life, one thing is certain, over a 34-year period, her many conquests and subsequent annexation of the territories conquered extended the borders of Zaria, which also grew in importance as a result and which became the center of the North-South Saharan trade and the East-West Sudan trade.

Makeda, The Queen of Sheba (960 BC)Edit

The Queen of Sheba, (Arabic Malekat sabaa ملكة سبأ, Ge’ez: Nigista Saba ንግሥተ ሳባ, Yoruba: Ayaba ile Seba) (Hebrew Malkat Shva: מלכת שבא), referred to in the Bible books of 1 Kings and 2 Chronicles, the New Testament, the Qur’an, Ethiopian history and even the tribal traditions of the Yoruba people of West Africa, was the ruler of Sheba, an ancient kingdom which modern archaeology speculates was located in present-day Yemen or Eritrea, Ethiopia.

Unnamed in the Biblical text, she is called Makeda (Ge’ez: ማክዳ mākidā) in the Ethiopian tradition, and in Islamic tradition her name is Bilqis. In some books she is referred to as Belkis. Alternative names given for her have been Nikaule, Nicaula and Bilikisu Sungbon. She supposedly lived in the 10th century BC.

She is better known to the world as the Queen of Sheba.

In his book, “World’s Great Men of Color”, J.A. Rogers, gives this description: “Out of the mists of three thousand years, emerges this beautiful story of a Black Queen, who attracted by the fame of a Judean monarch, made a long journey to see him.”[citation needed]

The Queen of Sheba is said to have undertaken a long and difficult journey to Jerusalem, in order to learn of the wisdom of the great King Solomon. Makeda and King Solomon were equally impressed with each other. Out of their relationship was born a son, according to the Ethiopian Book of the Glory of Kings, Menelik I.

This Queen is said to have reigned over Sheba and Arabia as well as Ethiopia. The queen of Sheba’s capital was Debra Makeda, which she built for herself.

In Ethiopia’s church of Axum, there is a copy of what is said to be one of the Tables of Law that Solomon gave to Menelik I.[citation needed] According to a king list presented by Ethiopian prince Tafari Makonnen, which draws on numerous Ethiopian traditions, Makeda supposedly ruled Ethiopia for 31 years from 1013 to 982 BC.[29]

The story of the Queen of Sheba is deeply cherished in Ethiopia as part of the national heritage. This African Queen serves as one of the exclusive group of people that appear in the traditions of several different religions, with her being mentioned in two holy books- the Bible and the Koran.

Usman dan FodioEdit

Shaihu Usman dan Fodio (Arabic: عثمان بن فودي ، عثمان دان فوديو) (also referred to as Shaikh Usman Ibn Fodio, Shehu Uthman Dan Fuduye, or Shehu Usman dan Fodio, 1754–1817) was a writer, preacher, Islamic reformer and Sultan of Sokoto. Dan Fodio was one of a class of urbanized ethnic Fulani living in the Hausa city-states in what is today northern Nigeria. He lived in the city-state of Gobir, and is considered an Islamic revivalist; he encouraged the education of women in religious matters, and several of his daughters emerged as scholars and writers (with the most prominent of them being the Princess Nana Asmau).

Dan Fodio was well-educated in classical Islamic science, philosophy and theology, and became a revered religious thinker in his own right. His teacher, Jibril ibn ‘Umar, argued that it was the duty and within the power of religious movements to establish the ideal society, free from oppression and vice. Dan Fodio used his influence to secure approval to create a religious community in his hometown of Degel that would, or so he hoped, be a model town.

After the Fulani War, he became the reigning commander of the largest state in the Africa of its day, the Fulani Empire. Dan Fodio worked to establish an efficient government, one grounded in Islamic law. Already aged at the beginning of the war, he retired in 1815 and passed the title of Sultan of Sokoto to his son, Muhammed Bello.

Dan Fodio’s uprising inspired a number of later West African jihads, including those of Massina Empire founder Seku Amadu, Toucouleur Empire founder El Hadj Umar Tall (who married one of dan Fodio’s granddaughters), Wassoulou Empire founder Samori, and Adamawa Emirate founder Modibo Adama, who served as one of dan Fodio’s provincial chiefs.

Queen Nzingha of Ndongo (1582–1663)Edit

Nzingha, Queen of Ndongo (1582–1663), was an Angolan monarch.

In the 16th century, the Portuguese stake in the slave trade was threatened by England and France. This caused the Portuguese to transfer their slave-trading activities southward to the Congo and South West Africa. Their most stubborn opposition, as they entered the final phase of the conquest of Angola, came from a queen who was a great head of state, and a military leader with few peers in her time. The important facts about her life are outlined by Professor Glasgow of Bowie, Maryland:

“Her extraordinary story begins about 1582, the year of her birth. She is referred to as Nzingha, or Jinga, but is better known as Ann Nzingha. She was the sister of the then-reigning King of Ndongo, Ngoli Bbondi, whose country was later called Angola. Nzingha was from an ethnic group called the Jagas. The Jagas were an extremely militant group who formed a human shield against the Portuguese slave traders. Nzingha never accepted the Portuguese conquest of Angola, and was always on the military offensive. As part of her strategy against the invaders, she formed an alliance with the Dutch, who she intended to use to defeat the Portuguese slave traders.”

In 1623, at the age of forty-one, Nzingha became Queen of Ndongo. She forbade her subjects to call her Queen, preferring to be called King, and when leading an army in battle, dressed in men’s clothing.

In 1659, at the age of seventy-five, she signed a treaty with the Portuguese, bringing her no feeling of triumph. Nzingha had resisted the Portuguese most of her adult life. African bravery, however, was no match for gunpowder. This great African woman died in 1663, which was followed by the massive expansion of the Portuguese slave trade.