Mound Bayou is a city in Bolivar County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,533 at the 2010 census,[2] down from 2,102 in 2000. It was founded as an independent black community in 1887 by former slaves led by Isaiah Montgomery.[3][4] Mound Bayou Historic District is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Mound Bayou, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname: Jewel of the Delta | |

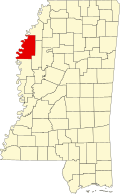

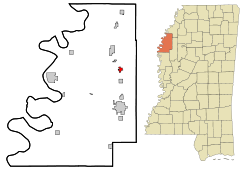

Location of Mound Bayou in Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 33°52′50″N 90°43′41″W / 33.88056°N 90.72806°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Bolivar |

| Founded | July 12, 1887 |

| Incorporated -City status | February 23, 1898 May 12, 1972 |

| Area | |

• Total | 0.88 sq mi (2.27 km2) |

| • Land | 0.88 sq mi (2.27 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 144 ft (44 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 1,534 |

| • Density | 1,749.8/sq mi (675.62/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 38762 |

| Area code | 662 |

| FIPS code | 28-49320 |

| GNIS feature ID | 2404316[2] |

| Website | www |

Mound Bayou is a city in Bolivar County, Mississippi, United States. The population was 1,533 at the 2010 census,[3] down from 2,102 in 2000. It was founded as an independent black community in 1887 by former slaves led by Isaiah Montgomery.[4][5] Mound Bayou Historic District is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[6]

Mound Bayou has a 96.8% African-American majority population in 2020, one of the largest of any community in the United States.

History

Mound Bayou traces its origin to freed African Americans from the community of Davis Bend, Mississippi. Davis Bend was started in the 1820s by planter Joseph E. Davis (elder brother of former Confederate president Jefferson Davis), who intended to create a model slave community on his plantation. Davis was influenced by the utopian ideas of Robert Owen. He encouraged self-leadership in the slave community, provided a higher standard of nutrition and health and dental care, and allowed slaves to become merchants.

In the aftermath of the Civil War, Davis Bend became an autonomous free community when Davis sold his property to former slave Benjamin Montgomery, who had run a store and been a prominent leader at Davis Bend. The prolonged agricultural depression, falling cotton prices, flooding by the Mississippi River, and white hostility in the region contributed to the economic failure of Davis Bend.

The two main founders of Mound Bayou in 1887 were Isaiah T. Montgomery, Benjamin's son, and Isaiah's cousin, Benjamin Titus Green.[7] Montgomery also served as the first mayor.[8]

The bottomlands of the Delta were a relatively undeveloped frontier, and freedmen had a chance to make money by clearing land and using the profits to buy lands in such frontier areas. In 1892, the Mound Bayou Normal Institute, a black school was founded by the American Missionary Association.[9]

African Americans throughout the United States celebrated the Mound Bayou example. In 1908, President Theodore Roosevelt ordered his train to make a special stop in the town. From the platform, he proclaimed that he was witnessing “an object lesson full of hope for the colored people and therefore full of hope for the white people, too.” Four years later, Booker T. Washington, in a speech to a crowd of thousands, hailed Mound Bayou as a “place where a Negro may get inspiration by seeing what other members of his race have accomplished...[and] where he has an opportunity to learn some of the fundamental duties and responsibilities of social and civic life.”[10]

In 1900 the Mound Bayou Industrial College (also known as the "Baptist College") was established for African American students, and active until 1936.[11]

By 1900 two-thirds of the owners of land in the bottomlands were black farmers. With the loss of political power due to state disenfranchisement, high debt and continuing agricultural problems, most of them lost their land and by 1920 were landless sharecroppers. As cotton prices fell, the town suffered a severe economic decline in the 1920s and 1930s.

The belief of Mound Bayou’s citizens in their role as promoting a black model of freedom and self-government was instrumental in weathering the decline in the two decades after World War I. No person was more effective in keeping the town afloat than Mayor Benjamin A. Green, a son of Benjamin Titus Green and the first person born in the community.[12] A Harvard Law School graduate, he won overwhelmingly for mayor in 1919 and served until his death in 1960. Green's diplomatic skills proved critical in navigating around external threats and keeping internal peace.[13]

In the 1920s, Green volunteered to be possible attorney for use by the NAACP in legal cases. His willingness to publicly align with that organization was not an exception in the community. Mound Bayou had a higher NAACP membership as a percentage of black population than any other Mississippi community.[13]

Shortly after a fire destroyed much of the business district, Mound Bayou began to revive in 1942 after the opening of the Taborian Hospital by the International Order of Twelve Knights and Daughters of Tabor, a fraternal organization. For more than two decades, under its Chief Grand Mentor Perry M. Smith, the hospital provided low-cost health care to thousands of black people in the Mississippi Delta. The chief surgeon was T.R.M. Howard, who eventually became one of the wealthiest black men in the state. Howard owned a plantation of more than 1,000 acres (4.0 km2), a home-construction firm, and a small zoo, and he built the first swimming pool for black people in Mississippi. [14]

In 1952, Medgar Evers moved to Mound Bayou to sell insurance for Howard's Magnolia Mutual Life Insurance Company. Howard introduced Evers to civil rights activism through the Regional Council of Negro Leadership which organized a boycott against service stations that refused to provide restrooms for black people. The RCNL's annual rallies in Mound Bayou between 1952 and 1955 drew crowds of ten thousand or more. During the trial of Emmett Till's killers, black reporters and witnesses stayed in Howard's Mound Bayou home, and Howard gave them an armed escort to the courthouse in Sumner.[15]

Author Michael Premo wrote:

"Mound Bayou was an oasis in turbulent times. While the rest of Mississippi was violently segregated, inside the city there were no racial codes ... At a time when blacks faced repercussions as severe as death for registering to vote, Mound Bayou residents were casting ballots in every election. The city has a proud history of credit unions, insurance companies, a hospital, five newspapers, and a variety of businesses owned, operated, and patronized by black residents. Mound Bayou is a crowning achievement in the struggle for self-determination and economic empowerment."[16]

Geography

U.S. Routes 61 and 278 bypass Mound Bayou to the west and lead south 9 miles (14 km) to Cleveland, the largest city in Bolivar County, and north 27 miles (43 km) to Clarksdale.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city of Mound Bayou has a total area of 0.9 square miles (2.3 km2), all land.

Demographics

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1900 | 287 | — | |

| 1910 | 537 | 87.1% | |

| 1920 | 803 | 49.5% | |

| 1930 | 834 | 3.9% | |

| 1940 | 806 | −3.4% | |

| 1950 | 1,328 | 64.8% | |

| 1960 | 1,354 | 2.0% | |

| 1970 | 2,134 | 57.6% | |

| 1980 | 2,917 | 36.7% | |

| 1990 | 2,222 | −23.8% | |

| 2000 | 2,102 | −5.4% | |

| 2010 | 1,533 | −27.1% | |

| 2020 | 1,534 | 0.1% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census[17] | |||

2020 census

| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[18] | Pop 2010[19] | Pop 2020[20] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 17 | 14 | 7 | 0.81% | 0.91% | 0.46% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 2,061 | 1,503 | 1,485 | 98.05% | 98.04% | 96.81% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0.05% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0.24% | 0.07% | 0.00% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00% | 0.00% | 0.00% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 1 | 0 | 5 | 0.05% | 0.00% | 0.33% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 9 | 1 | 26 | 0.43% | 0.07% | 1.69% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 8 | 14 | 11 | 0.38% | 0.91% | 0.72% |

| Total | 2,102 | 1,533 | 1,534 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

As of the 2020 United States census, there were 1,534 people, 641 households, and 376 families residing in the city.

2010 census

As of the 2010 United States census,[21] there were 1,533 people living in the city. The racial makeup of the city was 98.0% Black, 0.9% White, 0.1% Asian and 0.1% from two or more races. 0.9% were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

2000 census

As of the census[22] of 2000, there were 2,102 people, 687 households, and 504 families living in the city. The population density was 2,395.1 inhabitants per square mile (924.8/km2). There were 723 housing units at an average density of 823.8 per square mile (318.1/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 98.43% African American, 0.05% Native American, 0.24% Asian, 0.81% White, 0.05% from other races, and 0.43% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 0.38% of the population.

There were 687 households, out of which 38.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 24.7% were married couples living together, 43.7% had a female householder with no husband present, and 26.5% were non-families. 24.7% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.06 and the average family size was 3.66.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 34.7% under the age of 18, 12.9% from 18 to 24, 23.5% from 25 to 44, 19.1% from 45 to 64, and 9.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 27 years. For every 100 females, there were 78.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 67.6 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $17,972, and the median income for a family was $19,770. Males had a median income of $21,700 versus $18,988 for females. The per capita income for the city was $8,227. About 41.9% of families and 45.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 58.5% of those under age 18 and 34.5% of those age 65 or over.

Education

Primary and secondary schools

The city of Mound Bayou is served by the North Bolivar Consolidated School District,[23] which operates I.T. Montgomery Elementary School in Mound Bayou and Northside High School in Shelby. The elementary school is named after Mound Bayou cofounder Isaiah T. Montgomery.[24]

From its earliest years, Mound Bayou has struggled with inadequate educational infrastructure. According to a 1915 report in the Cincinnati Labor Advocate, Mound Bayou's school was attended by more than 300 students who were forced to make use of equipment held to be "inadequate for 50 pupils".[25] Teachers at the school were "poorly paid" and the school year limited to only five months.[25]

St. Gabriel Mission School in Mound Bayou was of the Roman Catholic Diocese of Jackson (formerly Roman Catholic Diocese of Natchez and Roman Catholic Diocese of Jackson-Natchez). It opened as a K-8 school on September 7, 1954. The high school opened in 1958. In 1961 the high school closed. Its non-preschool grades ended in 1994 when it was converted into a preschool. The preschool closed in 2001.[26]

On July 1, 2014, the North Bolivar School District consolidated with the Mound Bayou Public School District to form the North Bolivar Consolidated School District.[27] John F. Kennedy Memorial High School in Mound Bayou, formerly the secondary school of the Mound Bayou district, closed in 2018.[28]

Colleges and universities

Bolivar County residents have residency for two community colleges: Coahoma Community College and Mississippi Delta Community College.[29][30] Their main campuses respectively are in unincorporated Coahoma County and Moorhead in Sunflower County.

Health care

The last hospital in town closed in 1983.[31]

A branch of Delta Health Center is located in Mound Bayou.[32] Founded in Mound Bayou in 1967, Delta Health Center was the first rural community health center in the United States.[33]

Notable people

- Charles Banks (1873–1923) African-American businessman[34]

- Eugene P. Booze (1879–1939) African-American businessman[35]

- Mary Montgomery Booze (1878–1955), first African-American woman to sit on the Republican National Committee; born in Mound Bayou[36]

- General Crook, musician; born in Mound Bayou

- Medgar Evers (1925–1963), civil rights leader and soldier

- Myrlie Evers-Williams (born 1933), widow of Medgar Evers; civil rights leader, journalist, NAACP Chair

- Minnie L. Fisher, local community activist

- Lorenzo Gray (born 1958), baseball player; born in Mound Bayou

- Katie Hall (1938–2012), politician, U.S. Representative from Indiana from 1982 to 1985; born in Mound Bayou

- Fannie Lou Hamer (1917–1977), civil rights leader

- Kevin Henry (born 1968), football player; born in Mound Bayou

- Russell Holmes, Massachusetts state representative (6th Suffolk); born in Mound Bayou

- T. R. M. Howard (1908–1976), physician, surgeon, leader of civil rights and fraternal organizations, and entrepreneur

- Estella Montgomery (1882–1939), homicide victim

- Isaiah Montgomery (1847–1924), politician, town founder, mayor

- Harold Robert Perry (1916–1991), first African-American to serve as a Catholic bishop in the 20th century

- Melvin "Mel" Reynolds, politician; born in Mound Bayou

- Kelly Miller Smith Sr., preacher, author, and civil rights leader; born in Mound Bayou

- Lewis Ossie Swingler, journalist, editor, and newspaper publisher

- Ed Townsend, singer, songwriter, producer, and attorney

Cultural references

Mound Bayou was featured in the 2022 film, Till. The supporters of Emmett Till's mother, Mamie, were residents of the town and hosted her when she testified in the trial of her son's killers.[37] Mound Bayou was also mentioned in the 2025 film Sinners and is referenced in a piece on the soundtrack album entitled "Mound Bayou / Proper Black Folks".[38]

Ed Townsend wrote the Marvin Gaye hit song "Let's Get It On" in Mound Bayou.[39]

See also

- Mound Bayou Historic District

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Bolivar County, Mississippi

References

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Mound Bayou, Mississippi

- ^ "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Mound Bayou city, Mississippi". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 21, 2014.

- ^ Wormser, Richard (October 18, 2002). "Isiah Washington". Jim Crow Stories: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. Educational Broadcasting Corporation. Archived from the original on October 18, 2002. Retrieved October 18, 2002.

- ^ Educational Broadcasting Corporation (December 28, 2002). "Williams v. Mississippi (1898)". Jim Crow Stories: The Rise and Fall of Jim Crow. Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on December 28, 2002. Retrieved April 5, 2003.

- ^ "National Register of Historic Places Registration Form - Mound Bayou Historic District" (PDF). State of Mississippi.

- ^ Beito, David (October 10, 2023). "How Little Mound Bayou Became a Powerful Engine for African American Civil Rights and Economic Advancement". Independent Institute.

- ^ "Ernest Wright Principal Speaker at Mound Bayou". The Louisiana Weekly. July 6, 1968. p. 2. Retrieved October 1, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Hartshorn, W. N.; Penniman, George W., eds. (1910). An Era of Progress and Promise: 1863–1910. Boston, MA: Priscilla Pub. Co. p. 156. OCLC 5343815.

- ^ Beito, David (October 10, 2023). "How Little Mound Bayou Became a Powerful Engine for African American Civil Rights and Economic Advancement". Independent Institute.

- ^ "Article clipped from Jackson Advocate". Jackson Advocate. November 9, 1963. p. 45. Retrieved October 26, 2025 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mather, Frank Lincoln (1915). "Green, Benjamin A.". Who's Who of the Colored Race: A General Biographical Dictionary of Men and Women of African Descent. Vol. 1. Books on Demand. p. 120 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Beito, David. "Freedom's Outpost: Mound Bayou and the Right for Free Expression in Jim Crow Mississippi, 1887–1941". Independent Institute.

- ^ Beito, David T.; Beito, Linda Royster (2018). T.R.M. Howard: Doctor, Entrepreneur, Civil Rights Pioneer (First ed.). Oakland: Institute. pp. 53–57. ISBN 978-1-59813-312-7.

- ^ Beito, David T.; Beito, Linda Royster (2018). T.R.M. Howard: Doctor, Entrepreneur, Civil Rights Pioneer (First ed.). Oakland: Institute. pp. 83–84, 130–164. ISBN 978-1-59813-312.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: length (help) - ^ Premo, Michael (November 10, 2007). "Mound Bayou, Mississippi – The Jewel of the Delta". StoryCorps. Archived from the original on April 15, 2013.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Mound Bayou city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Mound Bayou city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Mound Bayou city, Mississippi". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 14, 2016.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "2020 CENSUS - SCHOOL DISTRICT REFERENCE MAP: Bolivar County, MS" (PDF). U.S. Census Bureau. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 12, 2021. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ Davis Betz, Kelsey (May 19, 2018). "Mound Bayou's history a 'magical kingdom' residents fight to preserve". Mississippi Today. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ a b "Hustling Town of Negroes Only Built in Mississippi," Labor Advocate [Cincinnati, OH], July 17, 1915, pg. 2.

- ^ "Lynch.pdf" (PDF). St. Gabriel Mercy Center. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 13, 2010. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "School District Consolidation in Mississippi Archived 2017-07-02 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Professional Educators. December 2016. Retrieved on July 2, 2017. Page 2 (PDF p. 3/6).

- ^ "Students staying home to protest high school consolidation". The Clarion Ledger. Associated Press. August 23, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "Student Residency Archived 2017-08-04 at the Wayback Machine." Coahoma Community College. Retrieved on July 8, 2017.

- ^ "Message from the President Archived July 4, 2017, at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Delta Community College. Retrieved on July 8, 2017.

- ^ Davis Betz, Kelsey (May 19, 2018). "Mound Bayou's history a 'magical kingdom' residents fight to preserve". Mississippi Today. Retrieved May 12, 2021.

- ^ "Our Locations". Delta Health Center. May 26, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2022.

- ^ Chatlani, Shalina (June 3, 2021). "With Roots In Civil Rights, Community Health Centers Push For Equity In The Pandemic". NPR.

- ^ Jackson Jr., David H. (July 10, 2017). "Banks, Charles". Mississippi Encyclopedia. Retrieved September 19, 2025.

- ^ "Eugene Booze Dies of Wounds". McComb Daily Journal (Obituary). November 8, 1939. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Eugene Booze And Wife Arrested Charged With Murdering Isaiah T. Montgomery". The Black Dispatch. Oklahoma City. August 11, 1927. p. 6. Retrieved September 26, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Emmett till movie shown in Black town pivotal to the story". Associated Press News. October 28, 2022.

- ^ Sinners (Original Motion Picture Score) at AllMusic. Retrieved May 6, 2025.

- ^ J. M. Martin (August 15, 2016). "Natural Resources". Oxford American. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

Further reading

- Hermann, Janet (1981). The Pursuit of a Dream. New York: OUP.

- David and Linda Royster Beito, T.R.M. Howard: Doctor, Entrepreneur, Civil Rights Pioneer (Oakland: Independent Institute), 2018. ISBN 978-1598133127.