In her youth, her people still practiced their traditional culture.

Truganini | |

|---|---|

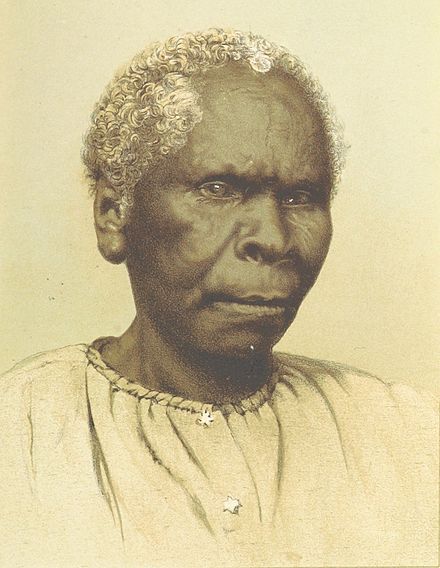

Truganini, c. 1866 | |

| Born | c. 1812 Recherche Bay, Van Diemen's Land, Colony of New South Wales |

| Died | 8 May 1876 (aged 63–64) Hobart, Colony of Tasmania |

Truganini (c. 1812 – 8 May 1876) was an Aboriginal Tasmanian woman who was widely described as the last surviving Aboriginal Tasmanian. A member of the Nuenonne people, she grew up on Bruny Island in south-eastern Tasmania. During her teenage years she saw the death and displacement of much of Tasmania's Aboriginal population as a result of European colonisation during the Black War. She became a guide to George Augustus Robinson and accompanied him on a series of expeditions that resulted in the exile of Tasmania's remaining Aboriginal population.

Truganini was herself exiled along with the surviving Aboriginal Tasmanians to the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment on Flinders Island in 1835. She later spent time in the Port Phillip District (modern-day Victoria), where she became a fugitive and was tried alongside four others for the murder of a pair of whalers. After being acquitted of the crime, she was returned to Wybalenna and was eventually moved to Oyster Cove. By 1872, she was the only Aboriginal resident left at Oyster Cove and began to be mythologised as the "last of a dying race", attracting the fascination of colonial scientists and the settler population.

After Truganini's death in 1876, the Tasmanian government declared the island's Aboriginal population to be extinct. Truganini became a symbol of her people's supposed extinction and has featured prominently in art, music, and literature. Once cast as the final survivor of a "doomed race", she has since been reframed by some as a memorial to the genocide of Indigenous Australians, and reclaimed by others as an anti-colonial resistance figure. The mythology of Truganini as the "last Tasmanian" has itself been challenged as part of broader efforts to contest the myth of Aboriginal Tasmanian extinction.

Early life

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Aboriginal population of Tasmania numbered around 3000 to 8000 people, forming nine nations divided into around 50–100 clan groups.[1][2] Truganini was born around 1812 at Recherche Bay in southern Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen's Land). She was the daughter of Manganerer, a senior Nuenonne man, whose country included Bruny Island and the coastal area of the Tasmanian mainland between Recherche Bay and Oyster Cove. Truganini's mother was likely a member of the Ninine people, another clan group from the Nuenonne's language group whose country encompassed the area surrounding Port Davey.[3]

By the time Truganini was born, the Nuenonne population had begun to encounter British colonisation. James Cook first landed on Bruny Island at Adventure Bay in 1777, and within a few decades former convicts began to conduct raids on Tasmanian Aboriginal communities to kidnap Aboriginal women. When a group of French explorers and scientists visited Bruny Island in 1802, they observed that the Nuenonne they encountered were terrified of the Europeans' guns and that the women refused to go near the visitors. After the establishment of the city of Hobart in 1804, a large number of ships began to sail past Nuenonne country to access the Derwent River.[4] In 1819, the Aboriginal and settler populations of Tasmania both sat at around 5000, with the settler population overwhelmingly made up of men.[5] By 1830, the settler population had grown to 23,500.[6]

Life at Missionary Bay

After the arrival of British settlers the seal colonies that the Nuenonne relied on were soon destroyed, leaving many women forced to trade sex for food with the settlers who had established whaling stations on the island. In 1816, Truganini's mother was murdered by a group of sailors, and in 1826, two of her sisters were kidnapped by a sealer.[7] According to an unverified account published shortly before Truganini's death, around 1828, Truganini was abducted and raped by timber cutters. According to the book, the timber cutters murdered two Nuenonne men, one of whom was her fiancé Paraweena, by throwing them out of a boat and cutting off their hands as they tried to clamber back in.[8][9][10]

By the late 1820s, Tasmania was in the midst of a conflict between colonists and Aboriginal Tasmanians known as the Black War. The kidnapping of Aboriginal women was common, and retributive violence between displaced Aboriginal Tasmanians and settlers was prevalent.[11][12] In 1828, the colony's governor George Arthur set up military posts to divide the settled districts, from which Aboriginal Tasmanians were to be excluded, from the rest of the island. In November of that year, driven by settler fears of Aboriginal guerrilla violence, he declared martial law within the settled districts.[13][14] The order did not extend to Bruny Island, where the less hostile relationship between the Nuenonne and the settler population was seen as making the island a suitable site for an attempt at conciliation with the Indigenous population. Arthur appointed George Augustus Robinson to set up a ration station and oversee the colonists' relationship with the Aboriginal communities on Bruny Island.[11][13] Robinson, who had migrated from London to Tasmania in 1824 to work as a builder, was a devout Christian who expressed religious and humanitarian motivations. He wrote that he hoped his efforts—modelled on the resettlement of Native Americans in the United States—would save the Aboriginal Tasmanian population from extinction.[15][16]

Robinson encountered Truganini while she was living amongst a group of convict woodcutters on the mainland. He brought her back to Bruny Island, where he established a Christian mission at Missionary Bay. He used Truganini's presence at the mission to entice her father and a small group of other Aboriginal people to join her. He deplored the widespread trade in sex between Aboriginal women and settlers, and attempted to convert the mission's residents to Christianity and put them to work in exchange for extra rations.[17] The mission quickly became stricken by disease, prompting its residents to seek to leave to escape its association with illness.[18] Truganini eventually deserted the mission to live at the whaling station at Adventure Bay, running away from Robinson when he attempted to retrieve her.[19]

In 1829, a group of escaped convicts kidnapped Truganini's stepmother. Manganerer attempted to follow them in a canoe but was blown out to sea, killing his son and almost killing him. When he returned to Missionary Bay, he found that almost the entirety of his clan group had died from disease. By early 1830, Manganerer had died from a sexually transmitted disease.[20] After the Nuenonne elder Woureddy—who Robinson viewed as an important ally—expressed a desire to marry her, Robinson retrieved Truganini from the whaling station. Despite initially expressing firm resistance, Truganini reluctantly agreed to marry Woureddy in October 1829.[21]

Guide for the "friendly mission"

In January 1830, Robinson obtained the governor's approval for a "friendly mission" to contact and gain the trust of the Aboriginal peoples of western and north-western Tasmania. He brought a group of Aboriginal guides, including Truganini, Woureddy, and two men named Kikatapula and Maulboyheenner, along with a small group of convicts. The party set out on foot from Recherche Bay on 3 February 1830.[22] Robinson's series of expeditions, which would ultimately continue until 1834, have been described by the genocide scholar Tom Lawson as a "roving embassy" that eventually negotiated an end to the violent conflict between settlers and the Aboriginal population.[23]

Truganini, who was suffering from an advanced case of syphilis, helped to collect food for the expedition party by diving for shellfish and gathering edible plants.[24] She also entered into a sexual relationship with Robinson's convict foreman Alexander McKay.[25] The group finally encountered a group of ten Ninine families shortly after passing Bathurst Harbour, and on 25 March they encountered another group and performed corroborees with them.[26] As the party continued their journey across western Tasmania, they learned of the increasingly violent massacres of Aboriginal Tasmanians that were taking place as part of the Black War.[27] About 60 settlers and 300 Aboriginal Tasmanians had been killed in the violence over the preceding two years.[28] They finished their journey in Launceston in October 1830, with Truganini so weakened that she could barely walk. With the colony under martial law, Truganini and the other Aboriginal guides were set to be imprisoned until an official secured their freedom and allowed Robinson's party to stay at his home.[29]

By the time of their arrival in Launceston, the governor had announced a policy known as the "Black Line" that required every man in Tasmania to join a militia. This militia would form two human chains to trap and remove every Aboriginal inhabitant of the settled districts.[30][31] Robinson reached an agreement with the governor that his expedition party would attempt to locate and make peace with any Aboriginal groups who evaded the Black Line, and would resettle them on Swan Island until a more permanent resettlement site could be established. Robinson quickly set out on this expedition with Truganini, Woureddy, an Aboriginal boy named Peevay, and two other guides to negotiate these groups' surrender before they could become victims of the Black Line.[32][33] He persuaded some sealers to release the Aboriginal women that they had enslaved, and convinced a number of Aboriginal people that he encountered, including a group led by the warrior Mannalargenna, to accompany him to Swan Island after warning them of the encroaching danger.[32][34]

Robinson brought the assembled party to the inhospitable Swan Island, which was exposed to powerful gales, had little food or clean water, and was infested with tiger snakes.[35] After securing his captives on the island, Robinson received a letter of praise from the military commandant for his efforts. While the 2200 militiamen of the Black Line had captured just two Aboriginal people over a chaotic seven weeks at a cost of more than £30,000, his small party had secured 15.[36][37] Robinson took Truganini and a few of his other Aboriginal guides to Hobart, where he met with the governor in early 1831. Robinson was rewarded with land grants and hundreds of pounds for the achievements of his friendly mission, while Truganini and the other guides were gifted some clothing and a boat.[38][a]

Guide for further expeditions

While the colony's executive encouraged Robinson to immediately set out on another mission to round up the colony's remaining Aboriginal population, Robinson persuaded the colony's governor and Aboriginal Committee that a permanent resettlement site should first be established for the surviving Aboriginal Tasmanians on Gun Carriage Island.[40][41] By 1831, the total number of Aboriginal Tasmanians had been reduced to a few hundred survivors.[42] On 1 March, Robinson took Truganini and 22 other Aboriginal Tasmanians from Hobart to Swan Island. There, he collected the 51 Aboriginal people who had been left on the island and continued towards the new resettlement colony. Despite complaints from Truganini and the other guides that they did not want to be resettled on Gun Carriage Island, Robinson expelled the sealers who had established a village there and turned the island into a resettlement station, giving Truganini and Woureddy one of the cottages that had been constructed by the sealers. Truganini refused to enter her cottage and began to beg Robinson to let her leave the island and return to the mainland.[43]

Expedition of 1831

In May 1831, Robinson took Truganini, Woureddy, Pagerly, Kikatapula, and Maulboyheener to a new mission that was being established at Musselroe Bay.[44] In late June, the group set out with Robinson on another expedition to capture a group of Aboriginal people led by Eumarrah.[45] Robinson was informed that the governor had decided to disestablish the settlement at Gun Carriage Island and had appointed him superintendent of a new Aboriginal resettlement station on Flinders Island, located about 65 kilometres northwest of the Tasmanian mainland.[46][42] After a few months, having had little success is locating Eumarrah, Robinson sought assistance from his rival Mannalargenna. Mannalargenna was furious with Robinson for breaking his earlier promises and for exiling him to Gun Carriage Island, but eventually agreed to assist him in tracking down Eumarrah.[47][48]

In mid-August Truganini separated from the rest of the group to care for Woureddy, who had suffered an injury to his thigh. By the time they reunited with the rest of the party on 31 August, the group had located Eumarrah and had been joined by two more Aboriginal women, including Mannalargenna's daughter Woretemoeteryenner. Eumarrah offered to work with Mannalargenna to help Robinson track down the rival Big River people.[49] The group returned to Launceston in September 1831, where newspapers reported with excitement on Eumarrah's promises to locate and round up the Big River people.[50] On 15 October Truganini, Robinson, and the other Aboriginal guides set out on this new expedition.[51] The group was forced to exercise caution as they traversed some of the colony's most settled regions, with Robinson believing that many of the settlers would kill his guides if given the opportunity.[52] On 30 December they located the group of 16 men, nine women, and one child, who were sent to join the 66 residents of the new resettlement station on Flinders Island.[53][54]

Expeditions of 1832 and 1833

Truganini was briefly taken to Flinders Island in February 1832, but departed with Robinson a few weeks later on his next expedition to round up a group of Aboriginal people known to be living in north-western Tasmania. Their short time on Flinders Island had left almost all of the Aboriginal guides in Robinson's party suffering from disease, and ultimately led to the deaths of Eumarrah and Kikatapula from influenza.[55][56] The party arrived at Cape Grim in early June and soon encountered a group of 23 Aboriginal people from the Peerapper clan. They were lured onto Hunter Island, where many died from illness before they could be sent to Flinders Island.[57][58]

In August, Truganini and the rest of the party set out in search of two more clan groups believed to be living in western Tasmania.[59] The following month, Truganini saved Robinson's life by swimming him across the Arthur River away from a group of Aboriginal warriors who intended to kill him.[60][61] By November, Truganini was assisting an expedition led by Anthony Cottrell to locate the Tarkiner clan group while Robinson travelled to Hobart. They gathered six individuals and sent them to Launceston, then returned to Macquarie Harbour to reunite with Robinson. In February 1833, Truganini set out on her own to hunt for a group of Ninine people and persuaded the group of eight to accompany her to Sarah Island.[62]

Robinson returned in late April, by which point several of the Ninine had escaped. With Robinson increasingly impatient to finish rounding up the remaining Aboriginal Tasmanians so that he could take up his post on Flinders Island, he became more willing to use force to collect the three remaining clan groups believed to be living on the mainland.[63][64] In May, Truganini led the party on another expedition and located a group of about 10 people, including the young daughter of Towterer. The group asked that they be permitted to reunite with Towterer and travel together, but Woureddy persuaded Robinson that they should instead force the group onto Sarah Island at gunpoint. In June, the party located Towterer and the Ninine group.[65]

In July, the party set out on another expedition to locate the remaining Tarkiner. Truganini helped to push the party's rafts across rivers, at one point suffering a seizure from the ordeal. While the expedition party eventually located most of the Tarkiner, all of the Tarkiner adults quickly died after being brought to Sarah Island. Only a handful of the Ninine and Tarkiner captives were still alive when they were sent to Flinders Island on 20 November.[66]

Expedition of 1834

On 14 January 1834 Robinson and his party left Launceston on what was intended to be their final expedition, and by April they had located 20 more Aboriginal people. While he was crossing the Arthur River on the return journey, Truganini again saved Robinson's life by swimming out to his raft and towing it to the bank after it was carried away by the swift current. Robinson left the expedition soon after and returned to Hobart, but placed his son in command of the expedition party and tasked them with finding the Tommigener clan. After enduring cold weather for four months, they found the eight remaining Tommigener in December, all of whom were already suffering from disease.[67]

Wybalenna and a final expedition

On 3 February 1835, Robinson declared that he had successfully located and exiled the entire Aboriginal population of the Tasmanian mainland.[b][69][70] The announcement was widely reported and was met with excitement by the settler population. He was awarded a sum of money, land grants for his sons, and a lifelong pension.[69] Robinson brought Truganini and the other Indigenous guides to his home in Hobart to recover from the long series of expeditions. Truganini and Woureddy had become celebrities in the colony, with Woureddy widely referred to as "Your Majesty", and they became the subjects of drawings by Thomas Bock and busts by the sculptor Benjamin Law.[71][72][73] In October 1835, however, they too were taken into exile at the Wybalenna Aboriginal Establishment on Flinders Island.[74]

Robinson expected that he would soon be transferred to the newly established Colony of South Australia and planned to bring the exiled Aboriginal Tasmanian population with him. He therefore regarded Flinders Island as a temporary resettlement site.[75][76] The conditions at Wybalenna were poor; of the 300 Aboriginal Tasmanians who had surrendered to Robinson since 1830, just 112 were left alive at Wybalenna in 1835. Many were suffering from disease, and there was little food or fresh water available on the island.[77][75] Robinson attempted to convert the residents to Christianity, changing their names and forcing them to wear European clothes. He renamed Truganini "Lalla Rookh" in reference to the romance of the same name by Thomas Moore. Truganini was forced to engage in sewing classes, but grew unhappy and expressed her desire to leave the island.[78]

In March 1836, Truganini joined another expedition to north-western Tasmania to locate the final group of Tarkiner people. This 16-month expedition provided an escape from Wybalenna and allowed the guides to return to the lifestyles to which they were accustomed.[79] When the group returned to Wybalenna, 16 of its inhabitants had died in their absence, and Truganini and the other guides had grown colder towards Robinson. When Robinson told them that he had constructed new houses on the island, Truganini remarked that soon there would be no one left alive to inhabit them.[80][81] Between 1835 and 1839, about half of the Aboriginal residents of Wybalenna died, with the majority of deaths at the settlement caused by pneumonia.[82][83]

Port Phillip District and trial

In 1839, Robinson took up the position of Protector of Aborigines in the newly colonised Port Phillip District in present-day Victoria. He took Truganini and about fifteen other Aboriginal Tasmanians with him; only six would eventually return to Tasmania.[81][84][85] Truganini and the other Tasmanians had few cultural ties to the Kulin people of the Port Phillip District, with whom they did not share a language. Robinson allowed the Tasmanians to live largely independently and eventually tasked one of his assistants, William Thomas, with caring for them. The men spent their time hunting and performing labour for Robinson's sons, while Truganini weaved baskets.[86][87]

Truganini ran away from the Aboriginal encampment several times.[88][89] By 1840, Robinson had decided he no longer had any use for the Tasmanians, and requested that arrangements be made to send them back to Wybalenna.[90] In 1841, Truganini abandoned her husband Woureddy and ran away with Maulboyheenner. They were soon joined by Peevay and two women called Plorenernoopner and Maytepueminer, and the five of them set out for Westernport Bay to search for Maytepueminer's husband Lacklay.[91] On 2 October they plundered and set fire to the hut of a settler named William Watson and kidnapped his wife and daughter. When Watson returned with his son-in-law, they shot and wounded the two men. While being pursued by an armed search party assembled by Watson, Maulboyheenner and Peevay shot and beat to death two whalers that they had mistaken for Watson and his party.[92]

Truganini and her four companions became outlaws, triggering a pursuit by the authorities across the Bass River and Tooradin regions. The group raided huts along the way and stole food, money, and weapons. Truganini became weakened by swelling in her legs, and within a few weeks could barely move.[93] An armed party under the command of Commissioner Frederick Powlett was tasked with apprehending them, and on 20 November, Powlett surrounded and ambushed the group with a party of 23 settlers and seven Aboriginal trackers.[94]

The five Tasmanians arrived in Melbourne as prisoners on 26 November. Maulboyheenner and Peevay were charged with murder, while the three women were charged as accessories. Maulboyheenner gave the defence that he had mistaken the whalers for Watson, and explained that they had been told by another settler that Watson was responsible for the death of Lacklay. Their appointed counsel Redmond Barry unsuccessfully argued that it was unfair to try members of an "alien people" in an unfamiliar courtroom. As the five defendants were not Christians, they were not permitted to testify; their lawyer was forced to enter a plea of not guilty on their behalf when it became clear that they did not understand what was taking place in the courtroom.[95][96]

At their trial Robinson testified to the positive character of the defendants. He also argued that Truganini and the other female defendants should not be blamed, as they were under the control of the men. The jury ultimately acquitted the three women but convicted Maulboyheenner and Peevay, while recommending a merciful sentence. The judge, John Walpole Willis, rejected their recommendation of mercy and sentenced the two men to death by hanging.[97][98] They were hanged on 20 January 1842 in front of a crowd of 4000–5000 people in what was the first legal execution to take place in the Port Phillip District.[99][73][90] According to the diaries of the minister Joseph Orton, Truganini was greatly anguished by their deaths.[100]

Oyster Cove

In July 1842, Truganini was transported back to Wybalenna on Flinders Island. Woureddy died on the journey, likely of syphilis. The superintendent forced the 54 remaining residents at Wybalenna to work, speak English, and practice Christianity. Truganini resisted these rules and often ran away with local sealers.[101][102][81] The superintendent forced her into a marriage with Mannapackername, also known as "King Alphonso", a senior member of the Big River people who he regarded as a responsible figure. While the superintendent hoped that this would curb Truganini's behaviour, both Truganini and Mannapackername continued to rebel against the conditions of their exile. After the residents sent petitions to Queen Victoria and to the colony's governor to protest their treatment, the colonial secretary ultimately decided in May 1847 that the Wybalenna settlement should be disestablished.[103][102][104]

It was decided that the 47 survivors at Wybalenna would be transferred to an abandoned convict settlement at Oyster Cove.[105] Following their arrival at Oyster Cover on 18 October 1847, the settler authorities largely abandoned their attempts to force the surviving Indigenous Tasmanians to adopt European practices. Truganini spent her time hunting possums and marsupials and diving for shellfish, and frequently returned to visit her country on Bruny Island.[106][107][108] The mortality rate at Oyster Cove was high, in part due to an influx of alcohol onto the station.[109][110] The practice of medicating the Aboriginal residents with mercury chloride likely also contributed to high rates of mental illness and psychotic disorders.[111] In 1855, an inspection of the settlement revealed that the residents were not being cared for and that living conditions were poor.[112]

A new superintendent, John Strange Dandridge, took over at Oyster Cove in July 1855 and made some improvements to the living conditions at the station.[113][102] In 1858, however, it was reported that alcohol abuse was prevalent among the residents. Truganini had entered a relationship with a younger Aboriginal man named William Lanne who was employed as a whaler and was violent towards her while drunk.[114][115] By 1859, there were only 14 surviving Aboriginal Tasmanians at Oyster Cove.[116][107]

The prospect that the Aboriginal population of Tasmania would soon become "extinct" triggered a wave of scientific interest in the survivors at Oyster Cove. Museums and collectors began to gather artefacts and human remains from the settlement. Truganini's remaining friend and clanswoman, Dray, died in 1861, leaving Truganini alone in her hut while Lanne was absent on whaling expeditions. She and the other survivors had become a curiosity for the settler population and were frequently photographed in studios in Hobart and at Oyster Cove. In 1868, Truganini and Lanne, who was christened "King Billy" and the "king of the Tasmanians", were presented to the Duke of Edinburgh.[117][118]

Lanne, who was understood to be the last surviving male Aboriginal Tasmanian, died on 3 March 1869. Amid a dispute over who should take possession of his body, his remains were mutilated and plundered by members of the Royal Society who wished to secure his skeleton for their collection.[119][120] Truganini, who was labelled the last "full-blooded" Aboriginal Tasmanian following his death, became the subject of even greater scientific curiosity. Disturbed by the treatment of Lanne's body, she begged a minister with whom she had developed a friendship to ensure that she would be buried at sea and that the museum collectors would not steal her body.[81][121]

Death

In 1872, with Truganini the only Aboriginal Tasmanian left living at Oyster Cove, it was decided that the land and buildings would be sold. Truganini was moved to Hobart to live in the family home of the last superintendent of the Oyster Cove station.[122] After Dandridge's death in 1874, she continued to be cared for by his widow, and in 1875 the Tasmanian government agreed to employ a nurse to care for her after she contracted bronchitis.[123][124] Widely described as the "last Tasmanian", Truganini attracted the fascination of Hobart's residents and received frequent visits from scientists and photographers in her final years. Truganini fell into a coma on 4 May 1876, and died on 8 May.[125][81] In the hours leading up to her death, she begged her doctor to ensure that she would be buried "behind the mountains" and that her body would not be mutilated by scientists.[124]

Remains and repatriation

After Truganini's death, the Secretary of the Royal Society requested her remains for scientific research. The Tasmanian government declined his request, but permitted the society to take a cast of Truganini's face.[126] Her body was buried at the former Female Factory in Hobart to protect her from body snatchers.[127][128] In 1878, after a campaign by the Royal Society, her body was disinterred with instructions that it should not be exhibited and should be used only for scientific purposes. Within a decade, however, her skull was put on public display at the Melbourne Centennial Exhibition. In 1904 Richard James Arthur Berry used her remains to create an articulated skeleton for display at the Tasmanian Museum along with several replicas, one of which was put on display at the Museum of Victoria.[128][129]

Campaigners began to demand in the 1930s that her remains be reburied according to her wishes. The Anglican Archdeacon Henry Brune Atkinson, the son of a minister who had grown close to Truganini in her final years, revealed in 1932 that his father's diaries reported that Truganini had feared that her body would be stolen by the museum and that she had pleaded with him to ensure that she would instead be buried at sea in the D'Entrecasteaux Channel.[127] Under pressure, the Tasmanian Museum ceased exhibiting her skeleton in 1947, but decided in 1951 that it would retain possession of her remains. The museum reached a permanent agreement, negotiated by the Bishop of Tasmania, to limit public access to the remains in 1954.[127][130][131] After legal efforts by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre, the Tasmanian government passed legislation in 1975 to transfer ownership of her remains from the museum to the Tasmanian government. Her remains were cremated and scattered in the D'Entrecasteaux Channel in 1976.[132][127] In 2002 and 2005, the Royal College of Surgeons returned additional samples of Truganini's skin and hair to the Tasmanian Aboriginal community.[73][133] Artefacts associated with Truganini have also been returned; in 1997, a necklace and bracelet belonging to Truganini that had first been displayed in Exeter in 1933 were returned by the Royal Albert Memorial Museum to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre.[134]

Legacy

Extinction myth

Upon the death of Truganini, the Tasmanian government declared the island's Aboriginal population to be extinct.[135][136][137] This narrative was reinforced by the widely read 1870 book The Last of the Tasmanians, which cast Truganini as the last remnant of her doomed people. These narratives often framed the Tasmanian Aboriginal population as a proud and noble people whose extinction was a sad but inevitable consequence of British colonisation.[138][139][140] The genocide scholar Tom Lawson argues that the extinction narrative served to reinforce the supposed power and superiority of the British Empire by presenting the Tasmanian Aboriginal community as having "simply been swept away by the might of the British Empire".[141]

The narratives that formed in the years surrounding Truganini's death led to an enduring popular belief that Tasmania's Aboriginal population had become extinct upon her death.[142][c] However, a substantial community of Aboriginal Tasmanians continued to be born on Cape Barren Island and other islands in the Furneaux Group.[146] This community, referred to as the "Islanders", were descended from the children of Aboriginal women and white sealers and were seen as "hybrids" by the colonists.[147][145] Their claims of Aboriginal identity were widely dismissed until the latter half of the 20th century on account of their mixed descent and the widespread view that Aboriginality was a fixed and biological characteristic that relied on "full-bloodedness".[145][146][148] Lyndall Ryan's 1981 book The Aboriginal Tasmanians was among the first works of history to challenge the extinction myth and establish the existence of a surviving community of Aboriginal Tasmanians.[136]

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the treatment of Aboriginal Tasmanians began to be recognised by some as an act of genocide.[145] Truganini's skeleton was removed from the Tasmanian Museum in 1947 amidst this growing discomfort.[145][128] In 1948, the writer Clive Turnbull published Black War: The Extermination of the Tasmanian Aborigines, in which he presented Truganini as an active figure who resisted the extermination of her people.[149] This new mythology influenced the creation of new artistic and literary depictions of Truganini as symbolic of the genocide perpetrated against the Tasmanian Aboriginal population.[150] The historian Rebe Taylor argues that Truganini became a symbol of white Australians' guilt at the extermination of her people.[136]

The late 1970s saw the emergence of post-colonial scholarship and a more vocal Aboriginal rights movement, including activism by the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre for the repatriation of Aboriginal remains.[151][152] This period also saw some revisionist accounts of Truganini's legacy. In 1976, Vivienne Rae Ellis published a controversial biography of Truganini titled Trucanini: Queen or Traitor? in which she presented Truganini as a "femme fatale" who betrayed her people by collaborating with European settlers.[153][154][155] In the 1990s, historiographies of the competing narratives surrounding Truganini's life and legacy began to be developed.[136] The cultural studies scholar Suvendrini Perera wrote in 1996 that Truganini had become "a marker of semiotic complexity ... her body is the site of competing narratives about power and powerlessness: agent or object, hostage or traitor, final victim or ultimate survivor?".[156] Truganini was also reclaimed as an anti-colonial figure by some members of the Aboriginal community.[157][136] Taylor writes that Truganini became "the national confessional" and the "poster girl of our national story of indigenous dispossession".[136]

Truganini also became a focal point in debates over the status of Tasmania's modern Indigenous population.[158] The 1978 documentary The Last Tasmanian rekindled the narrative that the Tasmanian Aboriginal population had become extinct upon Truganini's death.[158][159][160] The documentary prompted backlash from the modern Tasmanian Aboriginal community, who re-asserted their enduring culture and Aboriginal identity.[73][152] The community, including the activist Michael Mansell, condemned the documentary for denying the community's Aboriginality and disputed the narrative that Truganini had been the "last Tasmanian".[158] The community later protested a reference to Truganini as the "last Tasmanian" on the sleeve notes of the 1993 Midnight Oil song Truganini, arguing that it perpetuated the myth of Aboriginal Tasmanian extinction; the band eventually apologised.[161][2] According to Lawson, narratives of Tasmanian extinction and extermination have persisted in Britain into the twenty-first century.[162]

Cultural depictions

In 1997, Ryan wrote that Truganini had been the subject of more than fifty poems and fifty paintings and photographs, as well as about fifty scientific papers. She had also been the subject of a song, several novels and plays, and a stamp.[163] In these depictions, Ryan said that Truganini had been variously "revered, rebuked, sensationalised, sensualised, vilified, mocked, and politicised".[164] Some depictions of Truganini have been compared to those of Pocahontas, with both depicted as a "native princess" selflessly saving the life of a settler.[165][166]

In 2009, a group of Aboriginal Tasmanians protested at Sotheby's against the sale of copies of Benjamin Law's 1835 busts of Truganini and Woureddy. They were ultimately successful in having the sale cancelled after arguing that the community should be given the right to control how depictions of their ancestors could be used and put on display.[73] The protest became a flashpoint in debates about Aboriginal rights, with some conservative writers using the saga to condemn what one writer described as the radicalism of the "ultra-left Aboriginal fringe".[73][167] The art historian David Hansen wrote an essay on the debate titled Seeing Truganini, in which he argued that it was wrong to give contemporary Aboriginal communities the final say over artistic representations of Aboriginal history.[168]

One widely debated representation of Truganini is her portrayal in the 1840 Benjamin Duterrau painting The Conciliation. The painting depicts a meeting between Robinson and a group of Aboriginal Tasmanians, who agree to cease fighting and enter into exile.[169] In the book Black War, Turnbull argued that Truganini is depicted standing next to Robinson, symbolically attempting to resist the exile of her people.[136] Ellis, who argued that Truganini was a traitor to her people, argued that Truganini was instead the figure depicted second from the right in the act of betraying her people to Robinson.[170][171] Other historians have argued that Truganini is in fact one of the women depicted at the far back of the painting.[172] Ryan reinterpreted the painting as displaying tension between Robinson's Indigenous guides and the rival Big River people, arguing that the painting depicts the diversity of Indigenous Tasmanian experiences rather than representing Truganini's submission.[173]

See also

References

Notes

- ^ Despite persistently asking Robinson about their boat, the Aboriginal guides never saw or used the vessel they had been gifted. Robinson instead rented it out and kept the proceeds in an account he controlled.[39]

- ^ Robinson was unaware that at least one Tarkiner group, the Lannes, remained on the mainland. They would not be located until 1842.[68][69]

- ^ The belief that Truganini was the last "full-blooded" Aboriginal Tasmanian was also mistaken.[129] Two Aboriginal women from Tasmania who had been taken to Kangaroo Island in South Australia outlived Truganini.[136][143] Fanny Cochrane Smith and her descendants were also alive at the time of Truganini's death,[136][143] although whether Smith was a "full-blooded" or "half-caste" Aboriginal woman was debated.[144][145]

Citations

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 4.

- ^ a b McGrath 1995, p. 309.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 280–281.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 5–7.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 71.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 74.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 8–9.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 281.

- ^ Ellis 1976, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 268.

- ^ a b Ellis 1976, p. 27.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 87–88.

- ^ a b Pybus 2020, pp. 10–12.

- ^ McGrath 1995, pp. 319–320.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 151–153.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, pp. 70–71.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 12–15.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 74.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 20.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 21–22, 280.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 17, 22–24.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 24–30.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 68.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 32–34.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 41.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 35–40.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 45.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 130.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 49–50.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 51.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 130–131.

- ^ a b Pybus 2020, pp. 51–53, 61–62.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 176.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 179.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 65–66, 69.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 70.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 58.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 70, 74, 76–77.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 77, 87–88.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 182–183.

- ^ a b Lawson 2014b, p. 7.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 80–85.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 86.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 89, 91.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 94.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 188–189.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 97–100.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 105.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 108.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 182, 193.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 117–118.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 84.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 119–120, 123.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 200.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 124, 126–127.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 202–203.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 128.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 130–131.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 204.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 136–140.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 206.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 142–146.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 148–151.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 154–157.

- ^ Ellis 1976, p. 32.

- ^ a b c Pybus 2020, p. 158.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 214.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 161–163.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 164.

- ^ a b c d e f Hansen 2010.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 168.

- ^ a b Ryan 2012, p. 219.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 164–165, 169.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 175–176.

- ^ a b c d e Ryan & Smith 1976.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 239.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 104.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 177.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 237.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 113.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 186, 190–191.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 197.

- ^ Johnson & McFarlane 2015, p. 264.

- ^ a b Ellis 1976, p. 34.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 201–203.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 209–212.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 213–220.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 216, 220–221.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 222–224.

- ^ Johnson & McFarlane 2015, p. 271.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 225.

- ^ Johnson & McFarlane 2015, pp. 271, 274–275.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 225, 228.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 229.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 233–234.

- ^ a b c Ellis 1976, p. 35.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 236–239.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, pp. 117–119.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 239.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 241–242.

- ^ a b Lawson 2014b, p. 120.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 253.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 246.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 259.

- ^ Johnson & McFarlane 2015, p. 282.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 249–250.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 250–251.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 252, 256.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 265.

- ^ Ryan 2012, p. 262.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 254–259.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 262–265.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 260.

- ^ Onsman 2004, p. 42.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 261–262.

- ^ Pybus 2020, pp. 262–263.

- ^ Ellis 1976, p. 37.

- ^ a b Johnson & McFarlane 2015, p. 298.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 263.

- ^ Ryan 2012, pp. 269–270.

- ^ a b c d McKeown 2022, p. 31.

- ^ a b c Pybus 2020, pp. 265–266.

- ^ a b Ryan 2012, p. 270.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 266.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, p. 184.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 267.

- ^ Onsman 2004, p. 48.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, pp. 182, 190.

- ^ Ryan 1997, p. 157.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Taylor 2012.

- ^ Lawson 2014, p. 446.

- ^ Ryan 1997, pp. 157, 159.

- ^ Lawson 2014, pp. 446, 449.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, pp. 112–113.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, pp. 8, 154–156.

- ^ Onsman 2004, p. 39.

- ^ a b Ellis 1976, p. 38.

- ^ Taylor 2017, pp. 72–75.

- ^ a b c d e Ryan 1997, p. 161.

- ^ a b Taylor 2017, pp. 85–87.

- ^ Johnson & McFarlane 2015, p. 11.

- ^ Lawson 2014, pp. 453–454.

- ^ Ryan 1997, pp. 161, 163.

- ^ Ryan 1997, pp. 163–165.

- ^ Ryan 1997, p. 165.

- ^ a b Lawson 2014, p. 455.

- ^ Ryan 1997, p. 167.

- ^ Wilde, Hooton & Andrews 1994.

- ^ Ryan 2001.

- ^ Perera 1996, p. 395.

- ^ Ryan 1997, pp. 170–171.

- ^ a b c Ryan 1997, p. 169.

- ^ Onsman 2004, p. 46.

- ^ Lawson 2014, p. 453.

- ^ Perera 1996, p. 397.

- ^ Lawson 2014b, pp. 179–182.

- ^ Ryan 1997, p. 153.

- ^ Ryan 1997, p. 154.

- ^ Pybus 2020, p. 261.

- ^ Ryan 1997, p. 155.

- ^ Lehman 2011, p. 50.

- ^ Lehman 2011, pp. 50, 52.

- ^ Perera 1996, p. 403.

- ^ Ryan 1997, pp. 167–168.

- ^ Perera 1996, p. 404.

- ^ Ryan 1997, p. 168.

- ^ Perera 1996, pp. 404–405.

Sources

- Ellis, Vivienne Rae (1976). "Trucanini". Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association. 23 (2): 26–43. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- Hansen, David (2010). "Seeing Truganini". Australian Book Review. No. 321. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- Johnson, Murray; McFarlane, Ian (2015). Van Diemen's Land: An Aboriginal History. Sydney: University of New South Wales Press. ISBN 978-1-74224-189-0.

- Lawson, Tom (2014). "Memorializing Colonial Genocide in Britain: The Case of Tasmania". Journal of Genocide Research. 16 (4): 441–461. doi:10.1080/14623528.2014.975946.

- Lawson, Tom (2014b). The Last Man: A British Genocide in Tasmania. London: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-78076-626-3.

- Lehman, Greg (2011). "Fearing Truganini". Artlink. Vol. 31, no. 2. pp. 50–53. Retrieved 25 October 2025.

- McGrath, Ann (1995). Contested Ground: Australian Aborigines Under the British Crown. Oxon: Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-000-25665-9.

- McKeown, C. Timothy (2022). "Indigenous Repatriation: The Rise of the Global Legal Movement". In McKeown, C. Timothy; Fforde, Cressida; Keeler, Honor (eds.). The Routledge Companion to Indigenous Repatriation: Return, Reconcile, Renew. New York: Routledge. pp. 23–43. ISBN 978-1-351-39887-9.

- Onsman, Andrys (2004). "Truganini's Funeral". Island Magazine. No. 96. pp. 39–52. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- Perera, Suvendrini (1996). "Claiming Truganini: Australian National Narratives in the Year of Indigenous Peoples". Cultural Studies. 10 (3): 393–412. doi:10.1080/09502389600490241.

- Pybus, Cassandra (2020). Truganini: Journey Through the Apocalypse. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-76052-922-2.

- Ryan, Lyndall; Smith, Neil (1976). "Trugananner (Truganini) (1812–1876)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Vol. 6. Carlton: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84459-7. Retrieved 26 October 2025.

- Ryan, Lyndall (1997) [8 April 1997]. "The Struggle for Trukanini". Papers and Proceedings of the Tasmanian Historical Research Association. Peter Eldershaw Memorial Lecture. 44 (3): 153–173. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- Ryan, Lyndall (2012). Tasmanian Aborigines: A History Since 1803. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74237-068-2.

- Ryan, Lyndall (2001). "Truganini (Trukanini)". In Davison, Graeme; Hirst, John; Macintyre, Stuart (eds.). The Oxford Companion to Australian History. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195515039.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-551503-9.

- Taylor, Rebe (2012). "The National Confessional". Meanjin. Retrieved 23 October 2025.

- Taylor, Rebe (2017). Into the Heart of Tasmania: A Search for Human Antiquity. Melbourne: Melbourne University Publishing. ISBN 978-0-522-86797-8.

- Wilde, William Henry; Hooton, Joy Wendy; Andrews, Barry, eds. (1994). "Truganini". The Oxford Companion to Australian Literature. Melbourne: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195533811.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-553381-1.

External links

- Truganini (1812–1876), National Library of Australia, NLA Trove, People and Organisation record for Truganini

- Images of Truganini in State Library of Tasmania collection