The Walls of Benin are a series of earthworks made up of banks and ditches, called Iya in the Edo language, in the area around present-day Benin City, the capital of present-day Edo, Nigeria. They consist of 15 km (9.3 mi) of city iya and an estimated 16,000 kilometres (9,900 miles) of rural iya in the area around Benin.

| Benin Moat | |

|---|---|

| Native name Iyanuwo (Edo) | |

Interactive map of Benin Moat | |

| Type | Defensive fortification |

| Location | Benin City, Edo State, Nigeria |

| Nearest city | Benin City |

| Coordinates | 6°19′43″N 5°37′08″E / 6.3286°N 5.6189°E |

| Area | 814 acres (329 ha) |

| Elevation | 150 ft 1 in (45.75 m) |

| Height | Varies, over 20 m (66 ft) in places |

| Length | Approximately 16,000 km (9,900 mi) |

| Built | 13th century |

| Built by | Edo people |

The Benin Moat (Edo: Iyanuwo),[1] also known as the Benin City Iya, the Inner City Iya of Benin or the Wall of Benin, is a large earthwork within Benin City in Nigeria's Edo state, which formerly encircled the city at the time of the Benin Empire.[2] It is the central part of a series of connected earthworks surrounding the city which are collectively known as the 'Benin City Walls', consisting of the massive Inner City earthwork and much smaller, though more extensive Outer City earthworks.[3][2] Other earthworks are spread out across Edo State (known as the rural iya), and all of these earthworks are sometimes referred to collectively as 'the Walls of Benin'. All of these earthworks are known as Iya in the Edo language.[3] With the exception of a small part of the Benin City Iya, these structures are not really 'walls' but rather linear earthworks, consisting of a ditch and earth rampart known as a 'dump rampart'.[2] The Inner City Iya was built on a significantly larger scale with much taller ramparts and deeper ditches than any of the surrounding earthworks or other earthworks spread across the country, many of which are described as having a 'slight' and 'casual' profile.[2][3] Most of these earthworks only served to delineate boundaries, whereas the Inner City Iya served a defensive purpose.[2] Historical European accounts of the 'Benin Moat' or 'Benin City Wall' probably only refer to the Inner City Iya, though the accounts sometimes differ in their description of its structure.[2] Several wooden entrance gates are said to have existed, but 19th century accounts make no mention of them and their remains have yet to be identified by archeological research.[3] The Inner City Iya had a total length of approximately 12 kilometres (7.45 miles), though much of it has disappeared due to urban expansion and destruction in the modern era.[3] The combined length of all of the earthworks across the entire country, including ditches and ramparts and boundary traces, has been estimated to be approximately 16,000 kilometres (9,900 mi), covering about 6,500 square kilometres (2,500 sq mi) of land, though little remains today.[3][2] Whilst some sources have erroneously referred to these earthworks as comprising a single built structure, they actually consist of many different structures created at different times, some of which are connected and others which are not.[3] These earthworks have deep historical roots, with evidence suggesting their existence before the establishment of the Oba monarchy. Construction may have begun as early as 800 AD, continuing up to the modern era. The Inner City Iya itself was built in c. 1460 AD.[2] Its construction involved large-scale manual labour and the repurposing of earth from the outer ditch to build the inner rampart. It is estimated that a labour force of 5,000 men, working 10 hours a day, could have completed the work in 97 days, within the period of a single dry season.[2]

Today, remnants of the Iya can still be found in Benin City, although urbanisation and land disputes pose challenges to their preservation. Recognised for their historical significance, the Benin Iya have been placed on a tentative list of Nigerian World Heritage Sites, though they have yet to be included in the official list by UNESCO.[3] The Guinness Book of World Records describes 'The Linear Earthworks of Benin and Isha' as "the longest earthworks of the pre-mechanical era", though this refers to the estimated length of all the earthworks and boundary traces across the country combined and not specifically to the moat and rampart surrounding Benin City.[4]

History

Background

The origins of the Benin Moats, also known as the Walls of Benin, cannot be attributed to a single ruler or era.[5] While Oba Oguola played a role in expanding and deepening the moats, evidence suggests that these moats existed before his reign and even before the establishment of the Oba monarchy.[5] Various villages and wards that later coalesced into Benin City may have initially dug their moats for both defensive and boundary purposes.[6] The moat is an example of large-scale engineering by the Benin Empire.[7]

Construction

The earliest phase of moat construction in the Benin Kingdom likely predates the Ogiso kings. Archaeological findings and oral traditions suggest that some moats were in existence before the arrival of the Ogiso rulers.[8] These early moats served various purposes, including socio-political organisation, economic activities, and defense.[9]

During the rule of the Ogiso kings, the culture of moat construction continued and likely expanded. Moats varied in their origins and purposes. Different villages and wards within the Benin Kingdom had their moats, often constructed for distinct reasons. The Ogiso kings contributed to the development of some of these moats, maintaining control and organisation within the kingdom.[9] With the transition from the Ogiso kings to the Obas, the moat-building tradition persisted. Obas like Oba Oguola and Oba Ewuare re-dug and deepened some of these structures.Oba Oguola, who reigned around 1280 AD, also played a role in moat construction.[9]

The Benin City Moat itself was built around 1460 AD.[10] This defensive system comprised moats and ramparts protecting Benin City, while outer earthworks extended to encompass numerous villages and communities.[10] Manual labour was the sole means of construction, precluding the use of modern earth-moving equipment or technology. Earth excavated to create the moat was used to build the inner rampart. In some places the height from the bottom of the ditch to the top of the rampart reached 17 metres, with the ramparts themselves reaching up to 9 metres at their highest point.[2]

The moat and rampart, vigilantly guarded, functioned as an effective defensive line. It exposed invaders attempting to breach the city, resulting in their capture or meeting fierce resistance by Benin soldiers.[11] The steep earth banks posed an obstacle to invaders, who risked burial in sand avalanches. The towering rampart discouraged climbing, making invaders targets for Benin soldiers armed with spears and poisoned arrows.[12] The outer earthworks provided an additional layer of protection, effectively shielding the city. Strict access control was maintained through nine gates in the city rampart.[13] Within the city were located the Royal Palace and chiefs' residences.[13] Access through this fortified earthwork required payment of a toll, contributing to the city's reputation for safety by subjecting visitors, including traders, to thorough scrutiny.[14][15]

Urban core and protective moats

The heart of Benin City's historical landscape under the Kingdom of Benin covered an area exceeding 7 square kilometres (2.7 sq mi). It included the residences of the Oba (king), nobility, and indigenous inhabitants.[16] The city's layout revolved around two perpendicular streets: the principal sacred king's palace passage extending from the palace to the east, and a cross street connecting the King's Square to Oba Market, where slaves and ivory were traded.[17] The city's various communities extended along these streets and other minor ones.[18] The Benin Moat, possibly originally over thirty-five feet in width, surrounded the city and acted as a protective barrier.[19]

There were two distinct sections of the moat: the primary moat around the urban core and the sacred palace, and a secondary moat constructed later, encircling an area to the south.[20] Together, the moats and walls constituted defenses.[21]

Historical accounts

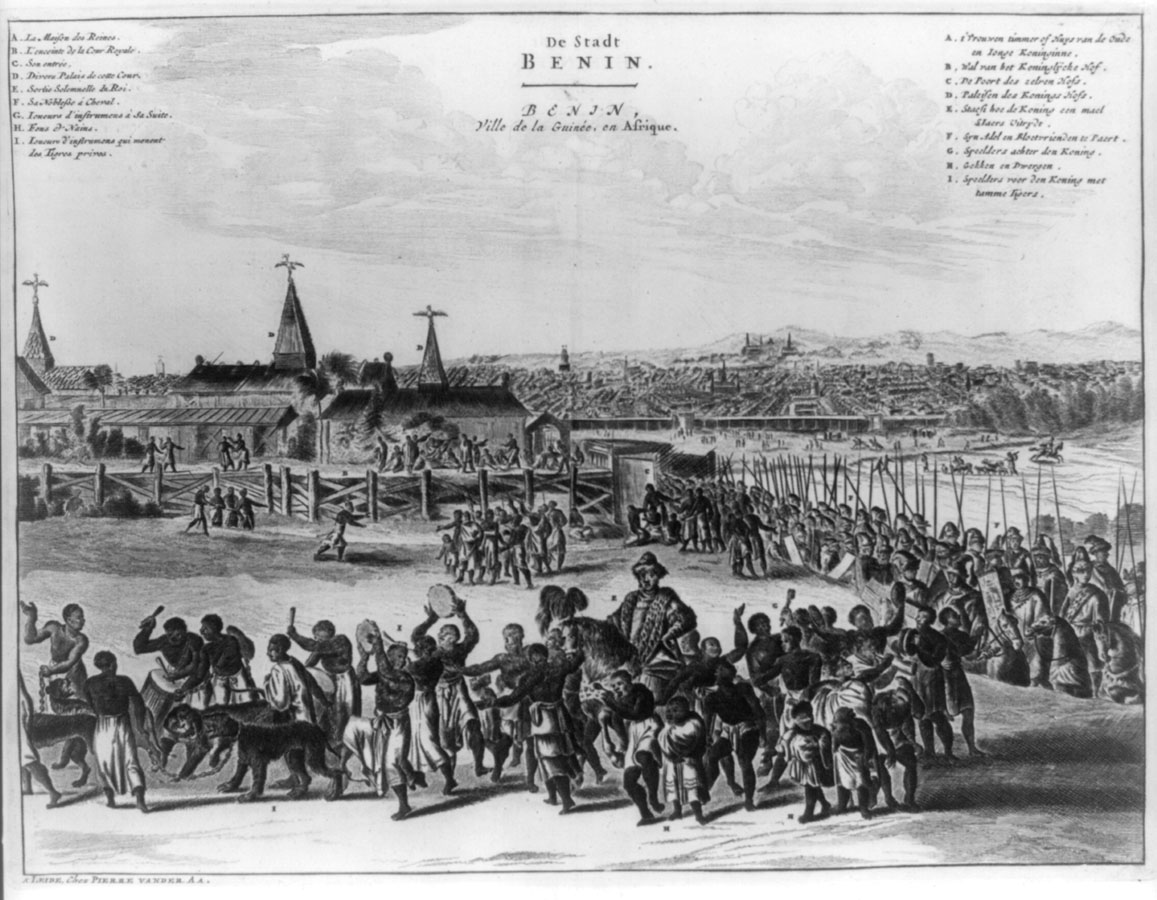

Various European authors wrote descriptions of the earthworks surrounding Benin City, either from first-hand or second-hand knowledge. These accounts date from those of Portuguese traders in the 16th century up to the British Punitive Expedition in 1897. The earliest written description of Benin City is from the Portuguese geographer and navigator Duarte Pacheco Pereira in his book Esmeraldo de Situ Orbis, dating from 1508:

the great city of Beny ... is about a league long from gate to gate; it has no wall but is surrounded by a large moat, very wide and deep, which suffices for its defence. I was there four times. Its houses are made of mud-walls covered with palm leaves.[22][a]

The archaeologist Graham Connah suggests Pereira's statement that there was 'no wall' may be due to him not considering a bank of earth to be a wall in the sense of the Europe of his day.[2] In c. 1600 the Dutch ship captain Dierick Ruiters gave a slightly more detailed description:

At the gate where I entered on horsebacke, I saw a very high Bulwarke, very thick of earth, with a very deepe broade ditch, but it was drie, and full of high trees ... That Gate is a reasonable good Gate, made of wood after their manner, which is to be shut, and there alwayes there is watch holden.[2]

A famous account is from the Dutch physician and author Olfert Dapper in his 1668 book Description of Africa. Dapper never visited Africa himself, but he compiled his book from the reports of Dutch travellers and missionaries who had explored various regions of the continent:

Benin shows itself, a city of that largeness, as cannot be equalled in those parts, and of greater civility than to be expected among such barbarous people ... It confines within the proper limits of its own walls three miles, but taking in the Court makes as much more. The wall upon one side rises to the height of ten feet, double pallisaded with great and thick trees, with spars of five or six foot, laid crossways, fastened together, and plastered over with red clay, so that the whole is cemented into one entirely, but this surrounds hardly one side, the other side having only a great trench, or ditch, and hedge of brambles, impassable, with little less difficulty than a wall, and consequently a good defence. The gates, being eight or nine foot high, and five broad, and made of one whole piece of wood, hang, or rather turns on a pin, in the middle, being the fashion of that country.[23][b]

Connah suggests that the 'timber revetting' described by Dapper might have existed at the points where the rampart was breached by gateways, and that this feature was presumed by the author or his informant to have been a general feature along the whole length of the wall. The thickness of vegetation shrouding the rampart at each side of the gate and completely filling the ditch might have obscured the rest from view.[2]

In 1820 a British Naval officer, Lieutenant John King, visited Benin city and wrote the following:

Benin is situated in a plain at the foot of an amphitheatre formed by hills which extend to the east, west, and north. The walls having been to a large extent destroyed and the city having been formerly depopulated by a civil war, the circumference of the inhabited area does not now exceed two or three miles.[24]

An account written in 1897 by Reginald Bacon, a member of the British Punitive Expedition, only briefly mentions the earthworks surrounding Benin City. The expedition force entered through one of the main entrances, which was defended by a wooden stockade armed with a Portuguese cannon:

Forcing on, we next met a stockade erected between two high banks through which the path ran. In front was a causeway over a ravine about twenty feet deep; in the stockade could be seen a gun.[25][c]

According to Bacon's account the city itself was about a mile beyond the large ditch and rampart, suggesting that the city had shrunk in size from its earlier peak. Bacon describes Benin city as "an irregular straggling town formed by groups of houses separated from each other by patches of bush. It is perhaps a mile and a half long from east to west, and a mile from north to south."[26]

Current state

The Benin City Moat is currently in a degraded state and risks further degradation from urban expansion.[3] Although some recent sources have claimed that the British punitive expedition in 1897 'destroyed' or 'heavily damaged' the Benin Moat,[27] there is no evidence for this from either historical or archaeological sources.[3][28][29] A survey in 1964 found that the ramparts and ditches were still largely complete, though the city had already begun to expand beyond the Moat and some damage had been done.[30] However since the 1960s urban development has spread rapidly and more than half of the original ramparts have been destroyed. Causes of the destruction include earth extraction for road repairs and bricks, flattening the ramparts or filling up of ditches to gain space for buildings, accelerated erosion and silting of the ditches from the drainage of streets, cutting gaps into the Iya to make way for streets, and using the moat as a dumping ground for refuse.[3][11] The 'rural iya' spread across Edo State have also suffered from destruction and neglect by local populations.[31]

Around 2007 the Benin Moat Foundation (BMF) was founded by the engineer Solomon Uwaifo with the aim of preserving the earthworks and promoting them for the purposes of tourism and national heritage.[16] Owaifo "was horrified by what he saw of the Benin moat today, compared with what he remembered when he was a boy.”[31] According to the BMF, during the period of colonial rule the British filled in parts of the moat to create roads for the city, and this continued after Independence as the need for new roads grew.[16] Many of the local population "see the moat as a nuisance – a gaping, useless hole", and as a convenient dumping ground, whilst the ramparts are seen as both obtrusive structures and as an easy source of building materials. The lack of a government-implemented master plan for the city or properly enforced laws has resulted in anarchy and corruption, and the absence of public waste management and drainage systems has further exacerbated the problem.[16] Nonetheless, today in parts of Benin City remains of the ancient moats still persist, visible as tree-lined embankments woven into the contemporary cityscape.

The moats encircling various towns and villages in Benin Metropolis historically served as boundaries. In many cases, these moats now encompass multiple villages, leading to complexity in areas like Benin City due to urban expansion and ongoing development for housing and industrial purposes.[10] As a result, some villages assert ownership claims over parts or the entirety of the moat enclosures, citing their longstanding presence in the area, even if it means displacing the original inhabitants.[6] Such claims have sometimes resulted in conflicts and disruptions in the region, where the interests of long-standing settlers have clashed with those of newer, more populous arrivals.[5] Land disputes in the courts often involve clashes between the original owners of Iya or moats enclosures and newer settlers claiming ancestral rights.[9]

Portions of the moats have yielded to residential and commercial development, experienced degradation from drainage projects, and been transformed into refuse disposal sites.[32] Certain sections of the moats, such as the area near Ogba Road, have succumbed to pollution and serve as dumping grounds for waste.[33] Preserving these historical assets necessitates comprehensive programs encompassing documentation, preservation, and vigilant safeguarding.[34]

Legacy

In 1961, shortly after Independence, the Benin Moat was proclaimed a national monument by the Nigerian government.[16] Recognised for their historical significance, the Benin Iya have been placed on a tentative list of Nigerian World Heritage Sites, though they have yet to be included in the official list by UNESCO.[3]

The Guinness Book of World Records describes 'The Linear Earthworks of Benin and Isha' as "the longest earthworks of the pre-mechanical era", though this refers to the estimated length of all the earthworks and boundary traces across the country combined and not specifically to the moat and rampart surrounding Benin City.[4]

Notes

References

- ^ Ebegbulem, Simon (25 March 2011). "National monument, Benin moat...On the edge of extinction". Vanguard News. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 12 October 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Connah 1967.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Schepers, Christian; et al. (2025). "Current Condition of the Iya in Benin City, the Gates and Future Preservation Strategies". African Archaeological Review. 42: 519–537. doi:10.1007/s10437-025-09630-y.

- ^ a b "Longest earthworks of the pre-mechanical era". guinnessworldrecords.com.

- ^ a b c "Benin Moat: Amazing legacy of great people". The Nation Nigeria. 21 May 2013. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ a b Ebegbulem, Simon (25 March 2011). "National monument, Benin moat...On the edge of extinction". Vanguard News. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ Onokerhoraye 1975, pp. 299–300.

- ^ "The Great Wall of Benin — Giving Children a Fighting Chance". SchoolForAfrica.org. 28 February 2021. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ a b c d "The Benin Moats". edoworld.net your Guide To The Benin Kingdom & Edo State, Nigeria. 1 July 2021. Archived from the original on 30 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ a b c Ogundiran, Akinwumi (June 2005). "Four Millennia of Cultural History in Nigeria (ca. 2000 B.C.–A.D. 1900): Archaeological Perspectives". Journal of World Prehistory. 19 (2): 133–168. doi:10.1007/s10963-006-9003-y. S2CID 144422848.

- ^ a b Connah 1967, pp. 593–609.

- ^ Daerego, Mary M.K. (6 August 2020). "GRANDEUR OF THE BENIN MOAT (ancient Benin civilization)". Observe Nigeria. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- ^ a b Graham 1965, pp. 317–334.

- ^ Trammell, Victor (20 September 2020). "Pre-Colonial Africa's Benin Moat Was Much Wider & Longer Than China's Great Wall". Black Then. Archived from the original on 29 October 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ "Benin's ancient moat wall turned dumpsite". Tribune Online. 16 June 2021. Archived from the original on 10 January 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e "HOME – BENIN MOAT FOUNDATION". beninmoatfoundation.org. 25 July 2011. Archived from the original on 3 March 2012. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Carvajal, Guillermo (17 October 2016). "Las murallas de Benin, la estructura más larga construída por el hombre, con 16.000 kilómetros de longitud". La Brújula Verde (in European Spanish). Archived from the original on 22 March 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Readman, Kurt (17 January 2022). "Mysterious and Massive: Who Built the Walls of Benin?". Historic Mysteries. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ @NatGeoUK (17 September 2022). "The story of Nigeria's stolen Benin Bronzes, and the London museum returning them". National Geographic. Archived from the original on 8 September 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Team, Editorial (19 November 2018). "The Ancient Walls of Benin: 16,000 Kilometres (800AD-14th Century)". Think Africa. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 25 August 2023.

- ^ Affairs, Edo (21 February 2023). "The Benin Moat – Largest Man Made Earthworks". Edoaffairs. Archived from the original on 25 August 2023. Retrieved 8 September 2023.

- ^ Pereira, Duarte Pacheco (1508). Esmeraldo De Situ Orbis. The Hakluyt Society; London; 1937. pp. 125–126.

- ^ Dapper, Olfert (1668). Description of Africa. p. 470.

- ^ Roth, Henry Ling (1903). Great Benin; its customs, art and horrors. F. King & Sons, ltd. p. 164.

- ^ Bacon, Reginald (1897). Benin: The City of Blood. Arnold. p. 80.

- ^ Bacon, Reginald (1897). Benin: The City of Blood. Arnold. p. 80.

- ^ Koutonin, Mawuna (2016). "Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace". theguardian.com.

- ^ Bacon, Reginald (1897). Benin: The City Of Blood. Arnold, London & New York.

- ^ Rawson, Geoffrey (1897). "Benin Punitive Expedition Report" (PDF).

- ^ Schepers, Christian; et al. (2025). "Current Condition of the Iya in Benin City, the Gates and Future Preservation Strategies". African Archaeological Review. 42: 519–537. doi:10.1007/s10437-025-09630-y.

- ^ a b Darling, Patrick; Agbontaen-Eghafona, Kokunre (2014). "Conservation Management of the Benin Earthworks of Southern Nigeria: A Critical Review of Past and Present Action Plans". The Protection of Archaeological Heritage in Times of Economic Crisis. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 341.

- ^ Maduka 2014, pp. 83–106.

- ^ Adekola et al. 2021.

- ^ Onwuanyi, Nwodo & Chima 2021, pp. 21–39.

Works cited

- Willett, Frank (1985). African Art: An Introduction (Reprint. ed.). New York: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20103-X.

- Connah, Graham (1972). "Archaeology in Benin". The Journal of African History. 13 (1). Cambridge University Press: 25–38. doi:10.1017/s0021853700000244. ISSN 0021-8537. S2CID 162976770.

- Connah, Graham (24 September 1967). "New Light on the Benin City Walls". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria. 3 (4). Historical Society of Nigeria: 593–609. ISSN 0018-2540. JSTOR 41856902. Archived from the original on 19 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Graham, James D. (1965). "The Slave Trade, Depopulation and Human Sacrifice in Benin History". Cahiers d'études africaines (in French). 5 (18). PERSEE Program: 317–334. doi:10.3406/cea.1965.3035. ISSN 0008-0055.

- Maduka, Chukwugozie (2014). "Preserving the Benin City Moats: The Interaction of Indigenous and Urban Environmental Values and Aesthetics". Environmental Ethics. 36 (1). Philosophy Documentation Center: 83–106. Bibcode:2014EnEth..36...83M. doi:10.5840/enviroethics20143616. ISSN 0163-4275.

- Onwuanyi, Ndubisi; Nwodo, Geoffrey; Chima, Pius (2021). "The Benin City Moat System: Functional Space Or Urban Void?". COOU African Journal of Environmental Research. 3 (1): 21–39. ISSN 2714-4461. Archived from the original on 19 September 2023. Retrieved 18 September 2023.

- Adekola, P. O.; Iyalomhe, F. O.; Paczoski, A.; Abebe, S. T.; Pawłowska, B.; Bąk, M.; Cirella, G. T. (11 January 2021). "Public perception and awareness of waste management from Benin City". Scientific Reports. 11 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 306. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-79688-y. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 7801630. PMID 33432016.

- Onokerhoraye, Andrew Godwin (1975). "Urbanism as an organ of traditional African civilization : The example of Benin, Nigeria / L'URBANISME, INSTRUMENT DE LA CIVILISATION AFRICAINE TRADITIONNELLE : L'EXEMPLE DE BENIN, NIGERIA". Civilisations. 25 (3/4). Institut de Sociologie de l'Université de Bruxelles: 294–306. ISSN 0009-8140. JSTOR 41229293. Archived from the original on 25 September 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- Nevadomsky, Joseph; Lawson, Natalie; Hazlett, Ken (2014). "An Ethnographic and Space Syntax Analysis of Benin Kingdom Nobility Architecture". The African Archaeological Review. 31 (1). Springer: 59–85. doi:10.1007/s10437-014-9151-x. ISSN 0263-0338. JSTOR 43916862. S2CID 254187721. Archived from the original on 25 September 2023. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- "The British Conquest of Benin and the Oba's Return". The Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 29 March 2023.

- Pearce, Fred (11 September 1999). "The African queen". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 15 November 2022.