“What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” is the title now given to a speech by Frederick Douglass delivered on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Society. The speech is perhaps the most widely known of all of Frederick Douglass’ writings save his autobiographies.

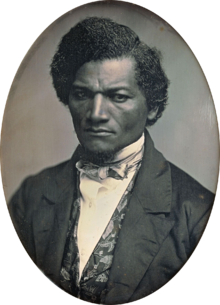

Frederick Douglass, circa 1852 | |

| |

| Date | July 5, 1852 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Corinthian Hall |

| Location | Rochester, New York, United States |

| Coordinates | 43°09′23″N 77°36′46″W / 43.15639°N 77.61278°W |

| Also known as | Oration, Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester by Frederick Douglass, July 5th, 1852 |

| Theme | Slavery in the United States |

| Cause | Abolitionism in the United States |

| Organized by | Rochester Ladiesʼ Anti-Slavery Society |

| Participants | Frederick Douglass |

| Transcript of speech | |

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?"[1][2] was a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society.[3] In the address, Douglass states that positive statements about perceived American values, such as liberty, citizenship, and freedom, were an offense to the enslaved population of the United States because they lacked those rights. Douglass referred not only to the captivity of slaves, but to the merciless exploitation and the cruelty and torture that slaves were subjected to in the United States.[4]

Noted for its biting irony and bitter rhetoric, and acute textual analysis of the U.S. Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and the Christian Bible, the speech is among the most widely known of all of Douglass's writings.[5] Many copies of one section of it, beginning in paragraph 32, have been circulated online.[6] Due to this and the variant titles given to it in various places, and the fact that it is called a July Fourth Oration but was actually delivered on July 5, some confusion has arisen about the date and contents of the speech. The speech has since been published under the above title in The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One, Vol. 2. (1982).[7]

Background

The Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society was founded in 1851. The inaugural meeting between six women took place in Corinthian Hall on August 20.[8] Frederick Douglass had moved to Rochester in 1847 in order to publish his newspaper The North Star.[9][10] He had previously lived in Boston, but did not want his newspaper to interfere with sales of The Liberator, published by William Lloyd Garrison.[10] Douglass had spoken at Corinthian Hall in the past. He had delivered a series of seven lectures about slavery there in the winter of 1850–51.[11] Additionally, he had spoken there less than three months prior to this speech, on March 25. In that speech, he cast the abolitionist movement as being engaged in a "War" against defenders of slavery.[12]

According to the 1850 Census, there were around 3.2 million slaves in the United States.[13] Although the import of people directly from Africa had been banned in 1807,[14] the domestic slave trade, still legal, was thriving. Over 150,000 persons were sold between 1820 and 1830, and over 300,000 were sold between 1850 and 1860.[15]

In 1850, the Fugitive Slave Act had passed Congress as part of the broader Compromise of 1850. This act forced people to report people who had escaped their enslavement and escaped to a free state, under punishment of a fine or imprisonment.[16] Additionally, it awarded $10 to a judge who sentenced an individual to return to enslavement, while awarding only $5 if the claim was dismissed.[16][17] Finally, the Act did not allow the accused individual to defend themselves in court.[17] This act drew the ire of the abolitionist movement,[9] and was directly criticized by Douglass in his speech.

Speech

The 4th of July Address, delivered in Corinthian Hall, by Frederick Douglass, is published on good paper, and makes a neat pamphlet of forty pages. The 'Address' may be had at this office, price ten cents, a single copy, or six dollars per hundred.

Douglass begins by saying that the fathers of the nation were great statesmen, and that the values expressed in the United States Declaration of Independence were "saving principles", and the "ringbolt of your nation's destiny", stating, "stand by those principles, be true to them on all occasions, in all places, against all foes, and at whatever cost." He then goes on to analyze the history of the United States, noting that 76 years ago in 1776 Americans were subjects of the British Crown. Douglass recounts the American Revolution, characterizing it as a just stand against oppression; "but we fear the lesson is wholly lost on our present ruler".[2]

Oppression makes a wise man mad. Your fathers were wise men, and if they did not go mad, they became restive under this treatment. They felt themselves the victims of grievous wrongs, wholly incurable in their colonial capacity. With brave men there is always a remedy for oppression.

Douglass then pivots to the present, stating that "We have to do with the past only as we can make it useful to the present and to the future". In spite of his praise of the Founding Fathers, he maintains that slaves owe nothing to and have no positive feelings towards the founding of the United States. He faults America for utter hypocrisy and betrayal of those values in maintaining the institution of slavery.

What, to the American slave, is your 4th of July? I answer: a day that reveals to him, more than all other days in the year, the gross injustice and cruelty to which he is the constant victim. To him, your celebration is a sham; your boasted liberty, an unholy license; your national greatness, swelling vanity; your sounds of rejoicing are empty and heartless; your denunciations of tyrants, brass fronted impudence; your shouts of liberty and equality, hollow mockery; your prayers and hymns, your sermons and thanksgivings, with all your religious parade, and solemnity, are, to him, mere bombast, fraud, deception, impiety, and hypocrisy—a thin veil to cover up crimes which would disgrace a nation of savages. There is not a nation on the earth guilty of practices, more shocking and bloody, than are the people of these United States, at this very hour.[18]

Douglass also stresses the view that slaves and free Americans are equal in nature. He expresses his belief in the speech that he and other slaves are fighting the same fight in terms of wishing to be free that White Americans, the ancestors of the white people he is addressing, fought seventy years earlier. Douglass says that if the residents of America believe that slaves are "men",[19]: 342 they should be treated as such.

Douglass then discusses the internal slave trade in America. He argues that though the international slave trade is correctly decried as abhorrent, the people of the United States are far less vocal in their opposition to domestic slave trade. Douglass vividly describes the conditions under which those enslaved are bought and sold; he says that they are treated as no more than animals.

The crack you heard, was the sound of the slave-whip; the scream you heard, was from the woman you saw with the babe. Her speed had faltered under the weight of her child and her chains! that gash on her shoulder tells her to move on. Follow the drove to New Orleans. Attend the auction; see men examined like horses; see the forms of women rudely and brutally exposed to the shocking gaze of American slave-buyers. See this drove sold and separated forever; and never forget the deep, sad sobs that arose from that scattered multitude. Tell me citizens, where, under the sun, you can witness a spectacle more fiendish and shocking. Yet this is but a glance at the American slave-trade, as it exists, at this moment, in the ruling part of the United States.

Building off of this, Douglass criticizes the Fugitive Slave Act, holding that in this act, "slavery has been nationalized in its most horrible and revolting form." He describes the legislation as "tyrannical", and believes that it is in "violation of justice".

After this, he turns his attention to the church. True Christians, according to Douglass, should not stand idly by while the rights and liberty of others are stripped away. Douglass denounces the churches for betraying their own biblical and Christian values. He is outraged by the lack of responsibility and indifference towards slavery that many sects have taken around the nation. He says that, if anything, many churches actually stand behind slavery and support the continued existence of the institution. Douglass equates this to being worse than many other things that are banned, in particular, books and plays that are banned for infidelity.

They convert the very name of religion into an engine of tyranny and barbarous cruelty, and serve to confirm more infidels, in this age, than all the infidel writings of Thomas Paine, Voltaire, and Bolingbroke put together have done.[19]: 344

Douglass believed that slavery could be eliminated with the support of the church, and also with the reexamination of what the Bible was actually saying.

Nevertheless, Douglass claims that this can change. The United States does not have to stay the way it is. The country can progress like it has before, transforming from being a colony of a far-away king to an independent nation. Douglass notes the difference between the attitude of American and British churches towards slavery, noting that in Britain "the church, true to its mission of ameliorating, elevating, and improving the condition of mankind, came forward promptly, bound up the wounds of the West Indian slave, and restored him to his liberty... The anti-slavery movement there was not an anti-church movement, for the reason that the church took its full share in prosecuting that movement: and the anti-slavery movement in this country will cease to be an anti-church movement, when the church of this country shall assume a favorable, instead or a hostile position towards that movement."[2]

Douglass then returns to the topic of the founding of the United States. He argues that the Constitution, when interpreted according to its principles rather than its compromises, does not permit slavery—a view that was controversial even among abolitionists.. He refers to the Constitution as a "Glorious Liberty Document".[2]

Analysis

A major theme of the speech is how America is not living up to its proclaimed beliefs. He talks about how Americans are proud of their country and their religion and how they rejoice in the name of freedom and liberty, and yet they do not offer those things to millions of their country's residents.[19]: 345 He also attempts to demonstrate the irony of their inability to sympathize with the Black people they oppressed in cruel ways that the forefathers they valorized never experienced. He validates the feelings of injustice the Founders felt, then juxtaposes their experiences with vivid descriptions of the harshness of slavery.[2]

However, if slavery were abolished and equal rights given to all, that would no longer be the case. In the end, Douglass wants to keep his hope and faith in humanity high. Douglass declares that true freedom cannot exist in America if Black people are still enslaved and is adamant that the end of slavery is near. Knowledge is becoming more readily available, Douglass said, and soon the American people will open their eyes to the atrocities they have been inflicting on their fellow Americans.

Essentially, Douglass criticizes his audience's pride for a nation that claims to value freedom though it is composed of people who continuously commit atrocities against Blacks. It is said that America is built on the idea of liberty and freedom, but Douglass tells his audience that more than anything, it is built on inconsistencies and hypocrisies that have been overlooked for so long they appear to be truths. According to Douglass, these inconsistencies have made the United States the object of mockery and often contempt among the various nations of the world.[19]: 346 To prove evidence of these inconsistencies, as one historian noted, during the speech Douglass claims that the United States Constitution is an abolitionist document and not a pro-slavery document.[20][21][22]

In this respect, Douglass's views converged with that of Abraham Lincoln's[23] in that those politicians who were saying that the Constitution was a justification for their beliefs in regard to slavery were doing so dishonestly.

The speech notes the contradiction of the national ethos of United States and the way slaves are treated. Rhetoricians R. L. Heath and D. Waymer refer to this as the "paradox of the positive" because it highlights how something positive and meant to be positive can also exclude individuals.[4]

Given that the speech was actually delivered on July 5, some scholars have placed it in the "Fifth of July" tradition of the commemoration of New York State emancipation.[24][25]

Later views on American independence

The speech "What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was delivered in the decade preceding the American Civil War, which lasted from 1861 to 1865 and achieved the abolition of slavery. During the Civil War, Douglass said that since Massachusetts had been the first state to join the Patriot cause during the American Revolutionary War, Black men should go to Massachusetts to enlist in the Union army.[26] After the Civil War, Douglass said that "we" had achieved a great thing by gaining American independence during the Revolutionary War, though he said it was not as great as what was achieved by the Civil War.[27]

Legacy

In the United States, the speech is widely taught in history and English classes in high school and college.[5] American studies professor Andrew S. Bibby argues that because many of the editions produced for educational use are abridged, they often misrepresent Douglass's original through omission or editorial focus.[5]

A statue of Douglass erected in Rochester in 2018 was torn down on July 5, 2020—the 168th anniversary of the speech.[28][29] The head of the organization responsible for the memorial speculated that it was vandalized in response to the removal of Confederate monuments in the wake of the George Floyd protests.[30]

Notable readings

The speech has been notably performed or read by important figures, including the following:

- James Earl Jones[5]

- Morgan Freeman[5]

- Danny Glover[5]

- Ossie Davis[5]

- Baratunde Thurston[31]

- Five of Douglass's descendants[32]

References

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1852). Frederick Douglass, Oration, Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester, July 5th, 1852. Rochester: Lee, Mann & Co., 1852. Rochester, NY: Lee, Mann & Co. Archived from the original on 2018-10-25. Retrieved 2018-10-25.

- ^ a b c d e Douglass, Frederick (July 5, 1852). "'What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?'". Teaching American History. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved January 2, 2022.

- ^ McFeely, William S. (1991). Frederick Douglass. New York: W.W. Norton & Company. pp. 172–173. ISBN 978-0-393-02823-2.

- ^ a b Heath, Robert L.; Waymer, Damion (2009). "Activist Public Relations and the Paradox of the Positive: A Case Study of Frederick Douglass's Fourth of July Address". Rhetorical and Critical Approaches to Public Relations II: 192–215. ISBN 9781135220877.

- ^ a b c d e f g Bibby, Andrew S. (July 2, 2014). "'What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?': Frederick Douglass's fiery Independence Day speech is widely read today, but not so widely understood". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 12, 2015. Retrieved August 13, 2015.

- ^ The paragraphing referenced here is taken from an edition of the speech at RhetoricalGoddess Archived 2019-07-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (1982). Blassingame, John W. (ed.). The Frederick Douglass Papers, Series One: Speeches Debates, and Interviews. Vol. 2, 1847–54. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 359–387.

- ^ "Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society papers (1848–1868)". William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ^ a b ""Frederick Douglass's, 'What To the Slave Is the Fourth of July?'"". National Endowment of the Humanities. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ^ a b Douglass, Frederick (1892). "Triumphs & Trials". Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. Boston, Mass.: De Wolfe & Fiske Co. ISBN 9780486431703.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Douglass, Frederick (2000). Foner, Philip S.; Taylor, Yuval. (eds.). Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings. Chicago Review Press. p. 163.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick (2000). Foner, Philip S.; Taylor, Yuval. (eds.). Frederick Douglass: Selected Speeches and Writings. Chicago Review Press. p. 486.

- ^ J. D. B. DeBow, Superintendent of the United States Census (1854). "Slave Population of the United States" (PDF). Statistical View of the United States. United States Senate. p. 82. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2021-11-04. Retrieved 2023-02-05.

- ^ Finkelman, Paul (2007). "The Abolition of The Slave Trade". New York Public Library. Retrieved 25 June 2014.

- ^ Pritchett, Jonathan B. (June 2001). "Quantitative Estimates of the United States Interregional Slave Trade, 1820–1860". The Journal of Economic History. 61 (2): 467–475. doi:10.1017/S002205070102808X. JSTOR 2698028. S2CID 154462144.

- ^ a b Cobb, James C. (18 September 2015). "One of American History's Worst Laws Was Passed 165 Years Ago". Time. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ^ a b Williams, Irene E. (1921). "The Operation of the Fugitive Slave Law in Western Pennsylvania from 1850 to 1860". Western Pennsylvania Historical Magazine. 4: 150–160. Retrieved 2023-02-03.

- ^ Battistoni, Richard. The American Constitutional Experience: Selected Readings & Supreme Court Opinions Archived 2022-03-01 at the Wayback Machine, pp. 66–73 (Kendall Hunt, 2000).

- ^ a b c d Douglass, Frederick (1852). "Oration, Delivered in Corinthian Hall, Rochester, July 5, 1852". In Harris, Leonard; Pratt, Scott L.; Waters, Anne S. (eds.). American Philosophies: An Anthology. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell (published 2002). ISBN 978-0-631-21002-3.

{{cite book}}: ISBN / Date incompatibility (help) - ^ Colaiaco, James A. (March 24, 2015). Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July. St. Martin's Publishing Group. ISBN 9781466892781. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Exceptionalism and the left". Los Angeles Times. December 13, 2010. Archived from the original on July 5, 2020. Retrieved July 3, 2020.

- ^ African Americans In Congress: A Documentary History, by Eric Freedman and Stephen A, Jones, 2008, p. 39

- ^ Gorski, Philip (February 6, 2017). American Covenant: A History of Civil Religion from the Puritans to the Present. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400885008. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved July 5, 2018 – via Google Books.

- ^ Mirrer, Louise; Horton, James Oliver; Rabinowitz, Richard (2005-07-03). "Opinion | Happy Fifth of July, New York!". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ Britton-Purdy, Jedediah (2022-07-01). "Opinion | Democrats Need Patriotism Now More Than Ever". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-05-15.

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. Frederick Douglass on Slavery and the Civil War: Selections from His Writings Archived 2022-07-05 at the Wayback Machine, p. 46 (Dover Publications, 2014): "We can get at the throat of treason and slavery through the State of Massachusetts. She was first in the War of Independence; first to break the chains of her slaves; first to make the black man equal before the law; first to admit colored children to her common schools, and she was first to answer with her blood the alarm cry of the nation, when its capital was menaced by rebels."

- ^ Douglass, Frederick. Autobiographies Archived 2022-07-05 at the Wayback Machine, p. 765 (Library of America, 1994): "It was a great thing to achieve American Independence when we numbered three millions, but it was a greater thing to save this country from dismemberment and ruin when it numbered thirty millions."

- ^ Schwartz, Matthew S. (July 6, 2020). "Frederick Douglass Statue Torn Down On Anniversary Of Famous Speech". NPR. Archived from the original on July 6, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Brown, Deneen L. (July 6, 2020). "Frederick Douglass statue torn down in Rochester, N.Y., on anniversary of his famous Fourth of July speech". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 7, 2020. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ Pengelly, Martin (July 6, 2020). "Frederick Douglass statue torn down on anniversary of great speech". The Guardian. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

Speaking to WROC, [Carvin] Eison asked: 'Is this some type of retaliation because of the national fever over Confederate monuments right now? Very disappointing, it's beyond disappointing.'

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: deprecated archival service (link) - ^ Thurston, Baratunde (July 4, 2020) [Recorded July 1, 2016]. Baratunde Delivers USA Co-Founder Frederick Douglass 1852 Speech: 'What To The Slave Is The 4th of July'. Facebook. Directed by Tara Garver Mikhael. Brooklyn Public Library. Archived from the original on July 5, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2020.

- ^ "VIDEO: Frederick Douglass' Descendants Deliver His 'Fourth Of July' Speech". NPR.org. Archived from the original on 2021-06-01. Retrieved 2021-05-22.

Further reading

- Bizzell, Patricia (1997-02-01). "The 4th of July and the 22nd of December: The Function of Cultural Archives in Persuasion, as Shown by Frederick Douglass and William Apess". College Composition and Communication. 48 (1): 44–60. doi:10.2307/358770. ISSN 0010-096X. JSTOR 358770.

- Boxill, Bernard R. (2009-11-18). "Frederick Douglass's Patriotism". The Journal of Ethics. 13 (4): 301–317. doi:10.1007/s10892-009-9067-x. JSTOR 25656264.

- Branham, R. (1998). "Abolitionist Reconstructions of July Fourth". ISSA Proceedings. Rozenberg Quarterly.

- Colaiaco, James A. (2006). Frederick Douglass and the Fourth of July. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403970336.

- Deyle, Stephen (Spring 1992). ""The Irony of Liberty: Origins of the Domestic Slave Trade"". Journal of the Early Republic. 12 (1). University of North Carolina Press: 37–62. doi:10.2307/3123975. JSTOR 3123975.

- Douglass, Frederick (1845). A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. New York: Dover Publications, Inc.

- Douglass, Frederick (2003). Stauffer, John (ed.). My Bondage and My Freedom: Part I – Life as a Slave, Part II – Life as a Freeman, with an introduction by James McCune Smith. New York: Random House.

- Douglass, Frederick (1994). Gates, Jr., Henry Louis (ed.). Frederick Douglass: Autobiographies. New York: Library of America. ISBN 0-940450-79-8.

- Duffy, BK; Besel, RD. "Recollection, Regret, and Foreboding in Frederick Douglass's Fourth of July Orations of 1852 and 1875". Making Connections: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Cultural Diversity. 12 (1).

- Harrill, J. Albert (Summer 2000). "The Use of the New Testament in the American Slave Controversy: A Case History in the Hermeneutical Tension between Biblical Criticism and Christian Moral Debate". Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation. 10 (2): 149–186. doi:10.2307/1123945. JSTOR 1123945.

- Higginson, Stephen A. (November 1986). "A Short History of the Right to Petition Government for the Redress of Grievances". The Yale Law Journal. 96 (1): 142–166. doi:10.2307/796438. JSTOR 796438.

- Lee, Sun-Jin (2014). ""Distance between This Platform and the Slave Plantation": Dissociation in Frederick Douglass's" What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?."". 영미연구. 30: 239–263.

- Lightner, David L. (Spring 2002). "The Founders and the Interstate Slave Trade". Journal of the Early Republic. 22 (1): 25–51. doi:10.2307/3124856. JSTOR 3124856.

- Maltz, Earl M. (October 1992). "Slavery, Federalism, and the Structure of the Constitution". The American Journal of Legal History. 36 (4): 466–498. doi:10.2307/845555. JSTOR 845555.

- Mayer, Henry (Spring 1999). "William Lloyd Garrison: The Undisputed Master of the Cause of Negro Liberation". The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education (23). The JBHE Foundation, Inc.: 105–109. doi:10.2307/2999331. JSTOR 2999331.

- McClure, KR (2000-12-01). "Frederick Douglass' use of comparison in his Fourth of July oration: A textual criticism". Western Journal of Communication. 64 (4): 425–444. doi:10.1080/10570310009374685.

- McDaniel, W. Caleb (March 2005). "The Fourth and the First: Abolitionist Holidays, Respectability, and Radical Interracial Reform". American Quarterly. 57 (1): 129–151. doi:10.1353/aq.2005.0014. JSTOR 40068253.

- Morgan, Philip D. (July 2005). "Origins of American Slavery". OAH Magazine of History. 19 (4). Oxford University Press: 51–56. doi:10.1093/maghis/19.4.51. JSTOR 25161964.

- Oakes, James (2007). The Radical and the Republican: Frederick Douglass, Abraham Lincoln, and the Triumph of Antislavery Politics. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc.

- Oshatz, Molly (June 2010). "No Ordinary Sin: Antislavery Protestants and the Discovery of the Social Nature of Morality". Church History. 79 (2): 334–358. doi:10.1017/S0009640710000065. JSTOR 27806397.

- Page, Brian D. (Winter 1989). ""Stand By the Flag": Nationalism and African-American Celebrations of the Fourth of July in Memphis, 1866-1887". Tennessee Historical Quarterly. 58 (4): 284–301. JSTOR 42627498.

- Parten, Bennett (September 2020). ""Blow Ye Trumpet, Blow": The Idea of Jubilee in Slavery and Freedom". Journal of the Civil War Era. 10 (3): 298–318. doi:10.1353/cwe.2020.0047. JSTOR 26977376.

- Trisha, Posey (2023-07-25). "Chapter 2: Frederick Douglass's Fourth of July Speech, Lament, and Historical Memory". In Fritz, Timothy; Posey, Trisha (eds.). "Blow Ye Trumpet, Blow": The Idea of Jubilee in Slavery and Freedom. Lexington Books. pp. 13–24. ISBN 9781666923131.

- Quigley, Paul (May 2009). "Independence Day Dilemmas in the American South, 1848–1865". The Journal of Southern History. 75 (2). Southern Historical Association: 235–266. JSTOR 27778936.

- Schwartz, Harold (June 1954). "Fugitive Slave Days in Boston". The New England Quarterly. 27 (2): 191–212. doi:10.2307/362803. JSTOR 362803.

- Shapiro, Ian; Feimester, Crystal; Stepto, Robert; Blight, David (Summer 2019). "Morton L. Mandel Public Lecture: A Conversation about Frederick Douglass" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. 72 (4): 13–21. JSTOR 27204397.

- Sherwin, Oscar (April 1945). "Trading in Negroes". Negro History Bulletin. 8 (7): 160–164. JSTOR 44214396.

- Smith, Richard (2022-12-22). "Learning from the abolitionists, the first social movement". British Medical Journal. 345 (7888): 56–58. JSTOR 23493402.

- Smith, Timothy L. (December 1972). "Slavery and Theology: The Emergence of Black Christian Consciousness in Nineteenth-Century America". Church History. 41 (4): 497–512. doi:10.2307/3163880. JSTOR 3163880.

- Stowe, David W. (Spring 2012). "Babylon Revisited: Psalm 137 as American Protest Song". Black Music Research Journal. 32 (1). Center for Black Music Research at Columbia College Chicago: 95–112. doi:10.5406/blacmusiresej.32.1.0095. JSTOR 10.5406/blacmusiresej.32.1.0095.

- Sweet, Leonard I. (July 1976). "The Fourth of July and Black Americans in the Nineteenth Century: Northern Leadership Opinion Within the Context of the Black Experience". The Journal of Negro History. 61 (3): 256–275. doi:10.2307/2717253. JSTOR 2717253.

- Wiecek, William M. (1977). The Sources of Anti-Slavery Constitutionalism in America, 1760-1848. Cornell University Press.

- Yang, Mimi (2023-10-25). "What Does the 250th Anniversary of the Independence Mean to a 'Browner' America?" (PDF). On_Culture. 15. doi:10.22029/oc.2023.1349. ISSN 2366-4142.

- Yuhl, Stephanie E. (August 2013). "Hidden in Plain Sight: Centering the Domestic Slave Trade in American Public History". The Journal of Southern History. 79 (3). Southern Historical Association.