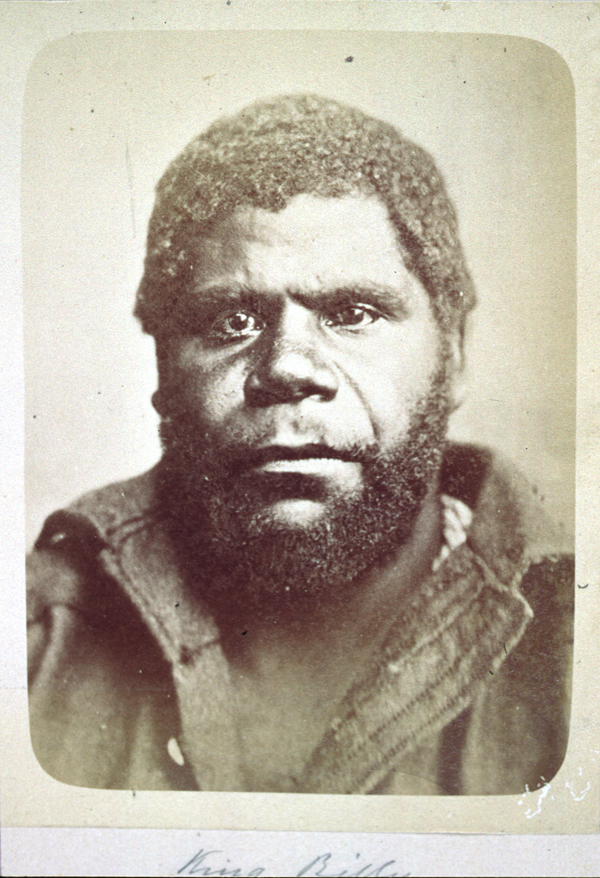

William Lanne (also known as King Billy or William Laney; c. 1835 – 3 March 1869) was a Tasmanian Aboriginal.

William Lanne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 1836 Tarkine, Van Diemen's Land |

| Died | 3 March 1869 Hobart Town, Tasmania |

| Burial place | St David's Park |

| Other names | Lanné, Laney, King Billy |

| Occupation | Whalemen |

| Years active | 1859–1869 |

| Known for | Last "full-blooded" Aboriginal man in Tasmania |

| Partner | Truganini (1864–1869) |

William Lanne (c.1836 – 3 March 1869), also spelt William Lanné and also known as King Billy or William Laney, was an Aboriginal Tasmanian man, known for being the last "full-blooded" Aboriginal man in the colony of Tasmania.

Early life

Lanne was born into the Indigenous Tarkinener clan of remote north-western Tasmania around 1836. He probably belonged to the last Aboriginal family group which was living a traditional lifestyle on mainland Tasmania after the policies of the colonial British government had either killed or removed almost the entire remaining Aboriginal population.[1][2]

In December 1842, Lanne's family group, which included his father and mother, his four brothers, and himself as a young child, made contact at Arthur River with employees of the Van Diemen's Land Company which had an extensive land grant in the region. His father answered to the name of "Lanna" or "Lanne" and this was the surname that was applied to the whole family.[2]

Exiled to Wybalenna

The Lanne family were quickly shipped off to the Aboriginal internment camp at Wybalenna on Flinders Island where around 180 other Tasmanian Aboriginal people were exiled after their forced removal from the mainland. At Wybalenna, Lanne was given the English first name of William and was reunited with his adolescent sister Victoria who had been taken by sealers before being sent to Flinders Island.[2]

The establishment at Wybalenna was poorly maintained and riddled with sickness. The previously healthy family rapidly succumbed to infectious respiratory diseases. Lanne's father, mother and two of his brothers died within a year of their arrival. His sister, Victoria, gave birth to a boy named George before she also died in 1847 along with another of his brothers. Victoria's skeleton is believed to have been later dug up from the Wybalenna cemetery and sold for the modern equivalent of €3,000 to the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences where her remains are still located.[2]

Oyster Cove and Hobart orphanage

In 1847, the forty-seven surviving Aboriginal people at Wybalenna were transferred to an equally unhealthy facility at Oyster Cove on mainland Tasmania. This group included William Lanne, his brother Charley and his infant nephew George. Charley was given to a local settler and was never heard of again. George died around 1852. William was sent to an orphanage in Hobart where he lived a miserable existence until 1853 when he was returned to Oyster Cove. William was the only child from Wybalenna who survived to adulthood.[2]

At the Oyster Cove Aboriginal establishment, Lanne was adopted by fellow Indigenous survivors, Walter George Arthur and his wife Mary Ann Robinson.[2]

Whaling

In 1855 the Tasmanian colonial government ordered that all able-bodied men and those of mixed descent from Oyster Cove were to find work outside the settlement. From 1859, Lanne found work as a whaler in the Tasmanian whaling and sealing industry. When on land he often resided in a local Hobart Town hotel such as the Dog and Partridge Hotel, alongside other shipmates and sailors. Lanne worked on many whaling ships, including the Aladdin, which sailed under the well-known whaler Captain McArthur, the Jane, the Runnymede and the Sapphire. The latter worked the waters of the Southern, Indian and Pacific Oceans.[3] Lynette Russell has argued that in all but one of the numerous existing portraits of Lanne he is wearing his whaling attire, confidently asserting his identity as a seaman.[4]

Lanne had a good-humoured personality, was well-spoken and admired among the Hobart community. He is recorded as advocating for improving the living arrangements of the women at Oyster Cove Settlement by writing to colonial officials in 1864. He formed a relationship with Truganini and was generally regarded as being her spouse during this period.[5][2]

In 1868, Lanne was a guest of honour at the Hobart Regatta, where he met the Duke of Edinburgh.[6] It is here that he was also introduced by the governor as the "King of the Tasmanians".[7]

Death

After returning from a whaling voyage on the Runnymede, which had been operating in the southern Pacific Ocean, Lanne was paid off and went to live at the Dog and Partridge Hotel at the corner of Goulburn and Barrack Streets in Hobart Town. Lanne died there two weeks later on 3 March 1869 from a combination of alcohol poisoning, cholera and dysentery. He was around 33 years old.[8][9]

Mutilation and theft of Lanne's corpse

Following his death, Lanne's body was mutilated and dismembered as part of a dispute between the Royal College of Surgeons and the Royal Society of Tasmania over who should possess his remains. A member of the Royal College of Surgeons named Dr William Crowther applied to the government for permission to obtain and send the skeleton to the college's headquarters in London, but his request was denied.[10]

Crowther ignored this decision and managed to break into the Hobart morgue where Lanne's body was kept. He dissected the corpse, removing Lanne's skull and replacing it with the skull of Thomas Ross, a recently deceased white school-teacher whose body was also in the morgue.[2][11]

However, Sir James Agnew and George Stokell, from the Royal Society of Tasmania, soon discovered Crowther's work, and decided to thwart any further attempts by Crowther to collect "samples" by amputating Lanne's hands and feet. After cutting off Lanne's appendages, Stokell gave them to his associate John Woodcock Graves who stuffed them in his pockets as he left the morgue.[12][2]

Lanne's funeral occurred the next day at St David's Church. It was organised by his whaling company employer who had his coffin draped in a possum-skin rug with spears placed on top. The captain of the Runnymede and three of Lanne's shipmates were pallbearers and they carried his casket to the church's cemetery where it was interred. The following morning, it was discovered that Lanne's grave had been dug up and the remaining parts of his corpse had been removed. Thomas Ross' skull which had been inserted into Lanne's head was found discarded amongst the other headstones. Ross' skull was placed into Lanne's empty coffin and re-interred.[2][13]

An enquiry was quickly organised into the theft of Lanne's body but was abandoned for political reasons. Stokell accused Crowther of stealing the corpse. Crowther, on the other hand, claimed he went to the hospital with a police escort where he found Stokell removing Lanne's bones from his corpse "in an indecent manner in which...messes of fat and blood were all over."[2]

Because he was accused of the theft of Lanne's head (and the illicit use of another white person's head), Crowther's honorary appointment as surgeon at the Colonial Hospital was terminated. Yet in 1869, the Council of the Royal College of Surgeons awarded him a gold medal and the first fellowship of the college ever awarded to an Australian.[10] Crowther later became Premier of Tasmania. Crowther claimed that, because Lanne had lived much of his life within the European community, his brain had exhibited physical changes, demonstrating "the improvement that takes place in the lower race when subjected to the effects of education and civilisation".[14]

Other colonists took note of Crowther's act:[15]

A fracas occurred outside the Council chamber, Hobart Town, a few nights ago. Mr. Crowther, member for Hobart Town, threatened his colleague, Mr. Kennerley, with personal violence, because of the latter's allusion to Mr. Crowther's alleged abstraction of the last aboriginal's head. Mr. Kennerley called the attention of the House to the circumstance, and Mr. Crowther was reprimanded.

— Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle, 15 August 1873

Crowther, it seems, retained Lanne's skull, which was probably donated to the Anatomy Department of the University of Edinburgh in 1888 by his son, Dr Edward Crowther. The rest of Lanne's skeleton appears most likely to have been retained in the Royal Society of Tasmania's museum.[2]

In the early 1990s, the University of Edinburgh repatriated a skull to the Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre (TAC) believed to be that of William Lanne. However, it is disputed that this was in fact Lanne's skull. It is possible that Lanne's skeleton was also given to the TAC for cremation in a batch of ancestral remains returned by the Royal Society around the same time.[14][2]

Legacy

William Lanne's name is believed to be the source of the "King Billy Pine", or Athrotaxis selaginoides, a native Tasmanian tree now classified as an endangered species, threatened by climate change.[16]

See also

References

- ^ Ryan, Lyndall (1981). The Aboriginal Tasmanians. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. p. 199. ISBN 0-7748-0146-8. OCLC 9461214.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Pybus, Cassandra (2024). A Very Secret Trade. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 9781761066344.

- ^ Russell, Lynette (2012). Roving mariners: Australian aboriginal whalers and sealers in the southern oceans, 1790-1870. Albany: State University of New York Press. p. 76. ISBN 978-1438444253. OCLC 859674439. Retrieved 15 May 2024.

- ^ Russell (2012), p. 78.

- ^ Fear-Segal, Jacqueline; Tillett, Rebecca (2013). Indigenous bodies: reviewing, relocating, reclaiming. Albany. p. 63. ISBN 978-1438448220. OCLC 860879571.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Lyndall (1981), p. 214.

- ^ Carey, Jane; Lydon, Jane (2014). Indigenous networks: mobility, connections and exchange. New York: Routledge. p. 105. ISBN 978-1-317-65932-7. OCLC 882771246.

- ^ Russell (2012), p. 82.

- ^ ""KING BILLY."". Illustrated Australian News For Home Readers. No. 144. Victoria, Australia. 19 April 1869. p. 93. Retrieved 4 June 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Davies, David (1973). "The last of the Tasmanians" Archived 24 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Frederick Muller, London. pp. 235-6.)

- ^ The Times, Saturday, 29 May 1869; pg. 9; Issue 26450; col E

- ^ Broome, Richard (2019). Aboriginal Australians: A History Since 1788. Allen & Unwin. p. 104. ISBN 978-1760528218.

- ^ "Funeral of King Billy—The Last Male Aboriginal". The Tasmanian Times. Vol. IIII, no. 460. Tasmania, Australia. 8 March 1869. p. 2. Retrieved 4 June 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Lawson, Tom (2014). The Last Man: A British Genocide in Tasmania. I.B. Tauris. pp. 166–168. ISBN 9781780766263.

- ^ "Tasmania". Nelson Examiner and New Zealand Chronicle. Nelson, New Zealand. 15 August 1873. p. 3.

- ^ "Athrotaxis selaginoides (King Billy pine) description". The Gymnosperm Database. 7 October 2017. Retrieved 19 August 2022.