Mabila (also spelled Mavila, Mavilla, Maubila, or Mauvilla, as influenced by Spanish or French transliterations) was a small fortress town known to the paramount chief Tuskaloosa in 1540, in a region of present-day central Alabama.The exact location has been debated for centuries, but southwest of present-day Selma, Alabama, is one possibility. In 1540 Chief Tuskaloosa arranged for more than 2500 native warriors to be concealed at Mabila, prepared to attack a large party of foreign invaders in the Mississippian culture territory:

| Battle of Mávilla | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Spanish colonization of the Americas | |||||

Discovery of the Mississippi, depicting the aftermath of the battle | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

| Habsburg Spain | Chiefdom of Tuskalusa | ||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||

| Hernando de Soto | Tuskaloosa | ||||

| Strength | |||||

| around 600 Spaniards | over 3,000 | ||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||

| 200 | 2,500-3,000? | ||||

Mabila[1] (also spelled Mavila, Mavilla, Maubila, or Mauvilla, as influenced by Spanish or French transliterations)[2] was a small fortress town known to the paramount chief Tuskaloosa in 1540, in a region of present-day central Alabama.[1] The exact location has been debated for centuries, but southwest of present-day Selma, Alabama, is one possibility. In late 2021, archaeologists announced the excavation of Spanish artifacts at several Native American settlement sites in Marengo County that indicate that they have found the historical province of Mabila, although not the town itself. They theorize that the town site is within a few miles of their excavations.[3]

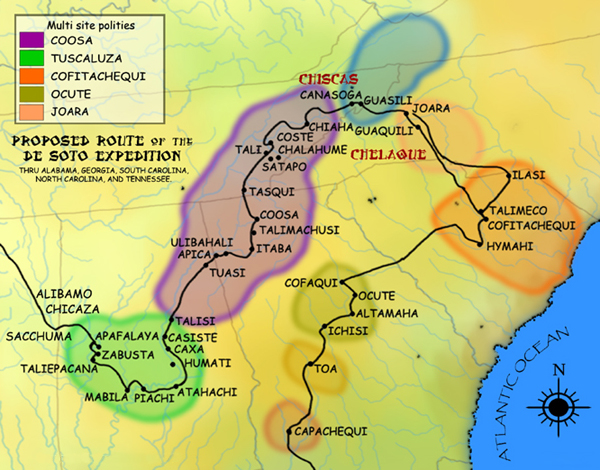

In 1540 Chief Tuskaloosa arranged for more than 2,500 native warriors to be concealed at Mabila, prepared to attack a large party of foreign invaders in the Mississippian culture territory: Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto and his expedition.[1]

When Hernando de Soto first met Tuskaloosa at his home village and asked him for supplies, Tuskaloosa advised them to travel to another of his towns, known as Mabila, where supplies would be waiting. A native messenger was sent ahead to Mabila. When Tuskaloosa arrived with the first group of Spaniards, he asked the Spanish people to leave the settlement and territory. A fight broke out between a soldier and a native, and many warriors emerged from hiding in houses and began shooting arrows at the Spaniards.[1] The Spaniards fled, leaving their possessions inside the fortress. The conflict that resulted is called the Battle of Mabila. Armed with guns, the Spaniards eventually burned down the village and killed most of the warriors.[1][4]

Fortress town

The walled compound of Mabila, one of many encountered by the Spaniards in their exploration,[1] was enclosed in a thick stuccoed wall, 16.5-ft (5-m) high. It was made from wide tree trunks tied with cross-beams and covered with mud/straw stucco, to appear as a solid wall.[1] The fortress was defended by Muskogee warriors, who shot arrows or threw stones.

Based on the earlier sources, Garcilaso de la Vega described the town of Mabila as: [1][2]

...on a very fine plain and had an enclosure three estados (about 16.5 feet or 5-m) high, which was made of logs as thick as oxen. They were driven into the ground so close together that they touched one another. Other beams, longer and not so thick, were placed crosswise on the outside and inside and attached with split canes and strong cords. On top they were daubed with a great deal of mud packed down with long straw, which mixture filled all the cracks and open spaces between the logs and their fastenings in such a manner that it really looked like a wall finished with a mason's trowel. At intervals of 50 paces around this enclosure, were towers capable of holding 7 or 8 men who could fight in them. The lower part of the enclosure, to 'the height of an estado' (5.55 feet), was full of loopholes for shooting arrows at those on the outside. The pueblo had only two gates, one on the east and the other on the west. In the middle of the pueblo, was a spacious plaza around which were the largest and most important houses. [1]

Battle of Mabila

The Spaniards suffered their greatest losses of the De Soto Expedition during the battle at Mabila, but the Mississippians suffered even more grievous losses.[1] De Soto had demanded supplies, bearers, and women from the powerful chief Tuskaloosa, when they met him at his main town. He said they needed to go to another settlement, and took them to Mabila.

On October 18, 1540, de Soto and the expedition arrived at Mabila, a heavily fortified village situated on a plain. It had a wooden palisade encircling it, with bastions placed so that archers could shoot their longbows to cover the approaches. Upon arriving at Mabila, the Spaniards knew something was amiss. The population of the town was almost exclusively male- young warriors and men of status. There were several women, but no children. The Spaniards also noticed the palisade had been recently strengthened, and that all trees, bushes, and weeds, had been cleared from outside the settlement for the length of a crossbow shot. Outside the palisade, they saw an older warrior in a field, who was seen exhorting younger warriors, and leading them in mock skirmishes and military exercises.[5]

When the Spaniards reached the town of Mabila, ruled by one of Tuskaloosa's vassals, the Chief asked de Soto to allow him to remain there. When de Soto refused, Tuskaloosa warned him to leave the town, then withdrew to another room, and refused to talk further.[1] A lesser chief was asked to intercede, but he would not. One of the Spaniards, according to Elvas, "seized him by the cloak of marten-skins that he had on, drew it off over his head, and left it in his hands; whereupon, the Indians all beginning to rise, he gave him a stroke with a cutlass, that laid open his back, when they, with loud yells, came out of the houses, discharging their bows."[1]

The Spaniards barely escaped from the well-fortified town. The Indians closed the gates and "beating their drums, they raised flags, with great shouting." De Soto determined to attack the town, and in the battle that followed, Elvas records: "The Indians fought with so great spirit that they, many times, drove our people back out of the town. The struggle lasted so long that many Catholics, weary and very thirsty, went to drink at a pond nearby, tinged with the blood of the killed, and returned to the combat."

De Soto had his men set fire to the town, then by Elvas's account,

breaking in upon the Indians and beating them down, they fled out of the place, the cavalry and infantry driving them back through the gates, where losing the hope of escape, they fought valiantly; and the Catholics getting among them with cutlasses, they found themselves met on all sides by their strokes, when many, dashing headlong into the flaming houses, were smothered, and, heaped one upon another, burned to death. They who perished there were in all 2,500, a few more or less: of the Catholics there fell 200... Of the living, 150 Catholics had received 700 wounds...

Elvas noted later that 400 hogs, and 12 horses died in the conflagration. But other contempary authors Ranjel-Oviedo and Garcilaso say 7 and 45 horses died in the battle, respectively.[6] The exact count of Indian dead is not known, but Spanish accounts at the time estimated that between 2,500 and 3,000 Indians had been killed by the raging fires within the city's walls. Spanish killed in action were either 22, 18, 25, 20, or 82 based upon the contemporary chroniclers of the time Ranjel-Oviedo, Elvas, Cañete, Biedma, and Garcilaso, respectively; with another 48 or more Spaniards dying from their wounds within days following the battle.[7] According to Garcilaso, "Most of the dead were women" who had followed their husbands, sweethearts, and others, to witness their glorious victory over the Castilians.[8] As for the Indian leader Tascalusa, neither he nor his body was ever found, and if he did perish in the burning city, his body would have been "burned beyond recognition."[9] In the "five centuries" of warfare between indigenous tribes and the European colonizers, the battle of Mabila is regarded as the first of the bloodiest battles ever fought in North America.[10][11]

See also

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Sylvia Flowers, "DeSoto's Expedition", U.S. National Park Service, 2007, webpage: NPS-DeSoto.

- ^ a b Related spellings: Mavila, Mavilla, Mauvilla.

- ^ "Mystery solved? Alabama researchers close in on pivotal battle site". 14 November 2021.

- ^ The single primary source about DeSoto's expedition was written by Hernández de Biedma. Another account, usually described as that of DeSoto's aide Rodrigo Ranjel, survives only partially in a summary history written by Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés. That secondary source had a strong influence on the formation of the text generally known as the Relaçam of the "Gentleman of Elvas" and, in turn, on the writing of Garcilaso de la Vega's Florida del Inca. (see review of The Hernando de Soto Expedition: History, Historiography, and Discovery in the Southeast in Journal of Interdisciplinary History 30.3, Winter 1999, webpage: SIU-G Archived 2009-03-17 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Charles Hudson (1998). Knights of Spain, Warriors of the Sun: Hernando de Soto and the South's Ancient Chiefdoms. University of Georgia Press. pp. 234–238. ISBN 978-0-8203-2062-5. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

- ^ Duncan p. 519

- ^ Duncan p. 382, 390, 518

- ^ Duncan p. 387

- ^ Duncan p. 388

- ^ Duncan p. 384

- ^ Tony Horwitz (April 27, 2009). A Voyage Long and Strange: On the Trail of Vikings, Conquistadors, Lost Colonists, and Other Adventurers in Early America. Macmillan. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-312-42832-7. Retrieved March 3, 2012.

References

- Duncan, David E. Hernando De Soto, A Savage Quest in the Americas. (1996) University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

- Sylvia Flowers, "DeSoto's Expedition", U.S. National Park Service, 2007, webpage: NPS-DeSoto.